Joan Waugh

“There is properly no history; only biography.” —Ralph Waldo Emerson Narrowing down a list of “books that built me” was surprisingly difficult. The books finally selected, four biographies and one autobiography, stand as touchstones marking different periods of my intellectual enlightenment, framing a lifelong interest in using the biographical method to understand the past. Emerson’s above quotation held meaning for me almost as soon as I learned how to read. I inhaled the volumes in Landmark Books’ marvelous American history series for young readers in the 1960s. One of my earliest touchstones came with Sterling North’s Abe Lincoln: Log Cabin to White House (1956), which sparked my passion for 19th-century U.S. history. I recently thumbed through my copy of North’s book with some trepidation, fearing that its power would be diminished by time. Not a chance. It remains an eminently readable and surprisingly sophisticated account of the 16th president’s life. The riveting character-driven story of Lincoln’s ascent introduced me to the notion that his life represented that of many thousands of others, providing a social history of the era. From then on, I was hooked on historical biographies as one way to comprehend the larger American experience.

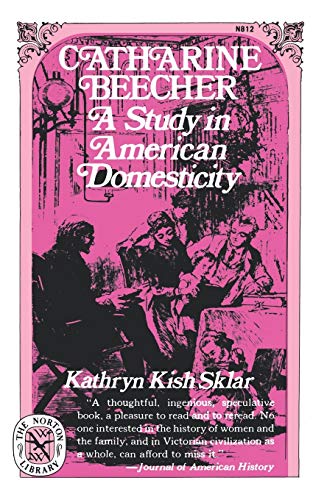

Kathryn Kish Sklar’s Catharine Beecher: A Study in American Domesticity (1976) furnished me with a scholarly touchstone during my graduate student years studying the Civil War era in the UCLA Department of History. It showed how a skillfully done biography goes beyond the life to enrich knowledge of the period. Sklar depicted a woman who wielded immense influence yet

remained largely unknown to a modern audience. Sklar questioned why, and deftly unpacked Beecher’s successful career as an author, educator, and reformer who produced “domestic science” treatises emphasizing the new technical skills women needed to become a power within the home. The oldest child of the remarkable Beecher family, Catharine’s long life was situated within the stormy era of religious, political, and cultural ferment through secession, war, and reconstruction. In recovering Catharine Beecher’s life and importance, Sklar also shed light on ordinary women’s domestic lives, demonstrating a striking female command in the private realm. This fascinating biography served as the inspiration for my first book, Unsentimental Reformer: The Life of Josephine Shaw Lowell(Harvard University Press, 1998). Josephine Lowell was the widow of one war hero and the grieving sister of another; her family’s urgent desire to memorialize their sacrifices incited my interest in exploring the contested realms between history and memory. My book revisited, reexamined, and restored an historical reputation that was relegated to a negative footnote despite Lowell’s exceptional list of achievements as an architect of the industrial welfare state, a power in private charity, and a force in political reform movements.

Two more touchstone books by prominent historians using the biographical method carried me into new scholarly terrain when I began an intensive study into the career of Ulysses S. Grant. The more I read on this impressive figure, the more I wondered how

and why his historical reputation had fallen so far so fast. The longtime consensus portraying him as a drunk, lucky general and an incompetent, corrupt president seemed astonishingly outdated. And then one day as I was doing research at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, James McPherson placed Brooks D. Simpson’s Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861–1868(1991) on my reader’s desk. It was a revelation. Simpson’s brilliant and meticulously researched volume convincingly overturned the negative scholarly interpretation of Grant that had prevailed for far too long. While not eliding Grant’s flaws and failures, Simpson’s riveting portrait of the complex soldier-statesman buoyed my growing conviction that his historical reputation, so associated with the “Union Cause,” had been distorted and downgraded to such an extreme degree that a correction grounded in memory studies would offer a balanced, and much needed, perspective.

Merrill Peterson’s Lincoln in American Memory(1994) also proved valuable during my research by suggesting a template for how to approach the delicate task of identifying, researching, and analyzing memory traditions. His observation that “The public remembrance of the past, as differentiated from the historical scholars’, is concerned less with establishing its truth than with appropriating it for the present” set the stage for his comprehensive, almost encyclopedia-like march through the myriad ways in which Lincoln had been remembered and commemorated. Whether venerated as savior of the Union, the great emancipator, or as a man of the people, Lincoln emerged over time with an iconic status from a great variety of sources, including images, poems, books, films, advertisements, political speeches, statues, rituals, and sacred sites. Collectively, the sources provided a compelling foundation for assessing Lincoln’s memory. Moreover, I appreciated the huge role that human emotion plays in constructing and nurturing any powerful memory tradition.

The martyred president never got the chance to write his memoirs, but his top general most famously did. Ulysses S. Grant’s autobiography is still heralded as great literature and history. It was with apprehension that I approached the Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant(1885), but that feeling was soon replaced with an appreciation for its designation as a “classic.” The clarity of the prose,

the flowing narrative, the imbedded sharp analysis, and the memoirs’ subsequent impact on the early formation of Civil War memory made it into an integral part of my subsequent publication, U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth(University of North Carolina Press, 2009). Fascinating too, that Grant’s powerful defense of the northern memory of the conflict could not stem the tide of favorable reaction given to those who molded the southern memory. I am currently writing a book examining the form, context, and consequences of Grant’s acceptance of “three surrenders” (from major Confederate armies at Fort Donelson, Tennessee, in 1862; at Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1863; and most famously at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, in 1865). Grant was relentless in pursuing victory, but once he had secured it, he also displayed a magnanimity that foreshadowed the troubled but ultimately successful reunion of the country. This project has required my constant return to the memoirs, and I am delighted this time to be able to peruse and profit from the first annotated edition of The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant(2017) edited by John F. Marszalek with David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo.

As may already be evident, I have dipped widely into 19th-century historical biographies as well as its first-person variant, the autobiography. Most of my published work features a biographical slant, and my lectures are replete with biographical vignettes. Early in my academic career I found to my surprise that I had to defend the uses and the effectiveness of the biographical “method” in historical practice. Although biographies remain by far the most favored way that Americans receive their history, many inside the academy frown on the genre, fearful that it too often offers simplistic hero worship that is antithetical to good history. I disagree. Fortunately, as my touchstone books demonstrate, even the most cursory examination of the lists from academic and popular presses reveals the biographical method is still flourishing. It seems to me that Ralph Waldo Emerson was right, after all.