Visitors to Gettysburg National Military Park pause during a tour of the battlefield.

Every one of you reading this magazine is a member of the public history world: you are a consumer (and possibly a producer) of history outside of a formal classroom setting. Public history is presented in museums and historical societies; at monuments or national, state, and local parks; at commemorative events and programs; and in newspapers, magazines, blogs, and websites. By any measure—the number of books published and sold, the number of visitors to battlefield parks, the amount of grass-roots fundraising for battlefield preservation, or membership in Civil War roundtable groups—the Civil War has long been the chapter in American history with the largest and most passionate public audience.

In other words, the state of Civil War public history is healthy. Or is it?

Like the rest of the public history profession, those who work in Civil War public history institutions are concerned about the future. They see a lot of white faces and gray hair in their audiences and at Civil War roundtable meetings around the country.

When asked about his organization’s strategy for recruiting new members, the now former director of a major state historical society used to quip, “Wait for people to turn 50.” Indeed, the core audience and membership of many history museums are successive generations of seniors. Americans tend to become more interested in history as they become empty nesters with more disposable income. Consumers of public history through traditional sources (museums, historic sites, and print publications) also tend to be white and more affluent than the average American.

Several developments have caused public history professionals to doubt whether the time-honored recruitment strategy of waiting for people to age into our world will continue to work. Is the widely publicized drop in visitors and financial resources at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, long a flagship of American public history sites, the proverbial handwriting on the wall?

One reason for the declines is the rise of digital technology. With computers and smartphones, people can access historical sites and information without physically visiting them. Historic sites—led by Colonial Williamsburg—have responded to this challenge by incorporating digital technology into their interpretations and creating “digital classrooms,” but the results have been mixed.

Interpreters mingle with tourists at Colonial Williamsburg.

Another challenge is changing demographics. America is becoming more diverse—racially, ethnically, and culturally. White people of European ancestry represent a declining percentage of the American population—which means, for instance, that a smaller proportion of Americans trace their ancestry back to either side in the Civil War. Will as many Americans continue to study the Civil War without this genealogical hook?

To reach new audiences, Civil War museums and historic sites need to convince people that the subject is worth their time and money. One way to accomplish this is to take history to the people, by offering programs at popular restaurants or bars.

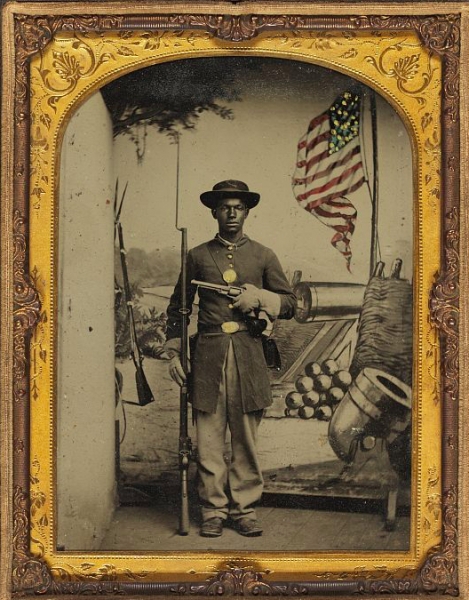

More to the point, public history institutions must convince non-visitors that the Civil War story is relevant to their lives and their identity. Specific to the Civil War, public and academic historians have for decades bemoaned and tried to counter the apparent disinterest among African Americans in the Civil War. Ideally, African Americans should be more interested in the Civil War than any other group of Americans. It was, after all, the war that brought freedom to 4 million enslaved African Americans. Yet African Americans generally have avoided Civil War sites, finding them irrelevant or even intimidating. One hopeful sign is the recent sesquicentennial observations, which succeeded in drawing more African Americans to commemorative events at historic sites by coupling the Civil War and em ancipation.

ancipation.

And what about people whose ancestors weren’t in the country when the Civil War was fought? Tony Horwitz begins Confederates in the Attic (1998) with an anecdote about his great-grandfather Isaac, a Jewish immigrant who arrived from Russia in 1882 and for whom a tattered copy of a Civil War book represented the essence of what it meant to be American. In promoting a recent airing of Ken Burns’ landmark series The Civil War, PBS featured a Japanese-American man explaining how he did not realize what it was to be an American until he watched the powerful documentary.

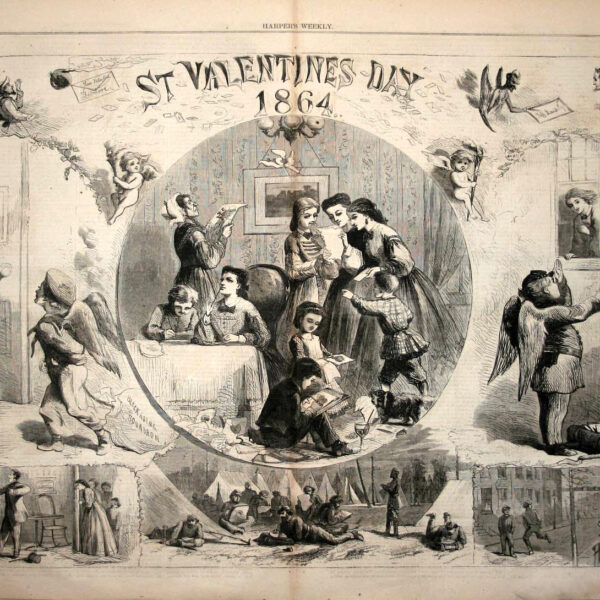

Indeed, the Civil War has always resonated in contemporary American life. Just consider the coincidence of the Civil War centennial occurring during the civil rights movement, which echoed so many issues of the century before. And just in the last three years, the legacies of the war have become more prominent than ever, with the Charleston, South Carolina, church murders and the ongoing national debates over Confederate monuments that resulted in the violent confrontations in Charlottesville, Virginia.

The hyper-relevance of the Civil War in the last few years represents both a problem and an opportunity. Public history, by definition, mirrors our public interests and debates. And, as we all know, the American public is badly fractured along demographic, political, and ideological lines. But that very polarization offers museums and parks an opportunity to underscore their value as trustworthy sources for objective and constructive background and perspective.

Many public history institutions and popular publications (including this one) have engaged the debates head on. And rather than defend the status quo of the inherited commemorative landscape, public historians have showcased diverse, conflicting voices on hot-button issues. Professional organizations such as the National Council on Public History and the American Association for State and Local History have endorsed a formal statement from the American Historical Association (the flagship academic historical organization) that is severely critical of Confederate monuments and other vestiges of the Lost Cause narrative of Civil War history.

In short, public history professionals are seeking to make the Civil War more attractive and more politically palatable for people who have not been interested in the subject as it was taught in schools and presented at historical sites until recent decades.

Obvious questions must occur to those of you reading this column—you who have, after all, proven willing to pick up a printed magazine and voluntarily read about Civil War history: What about us, the people who don’t need to be convinced that the Civil War is interesting and important? What about those of us who grew up with Douglas Southall Freeman, Bruce Catton, Shelby Foote, and Robert Penn Warren waxing poetical on America’s “Homeric Period”? Aren’t we part of the “public” in “public history”?

An unidentifed African-American Union soldier

The ways that public historians are trying to attract new audiences—including emphasizing non-military aspects of the conflict and repudiating the Confederate side of the story—may seem hostile to the more traditional ways of studying the Civil War. Yes, of course, the Civil War’s most significant results were the preservation of the Union and emancipation of 4 million enslaved African Americans. And 200,000 African-American troops fought for the Union. And southerners were not as unified behind the Confederacy as we once believed. But what about the majority experience? What about the millions of white Americans on both sides who fought and endured the Civil War? Is it no longer possible to study the war as a military contest between two sides whose leaders and soldiers exhibited all the noble and ignoble characteristics of human beings? Does emphasizing “relevance” mean that the only legitimate way of studying the war will be as a morality play?

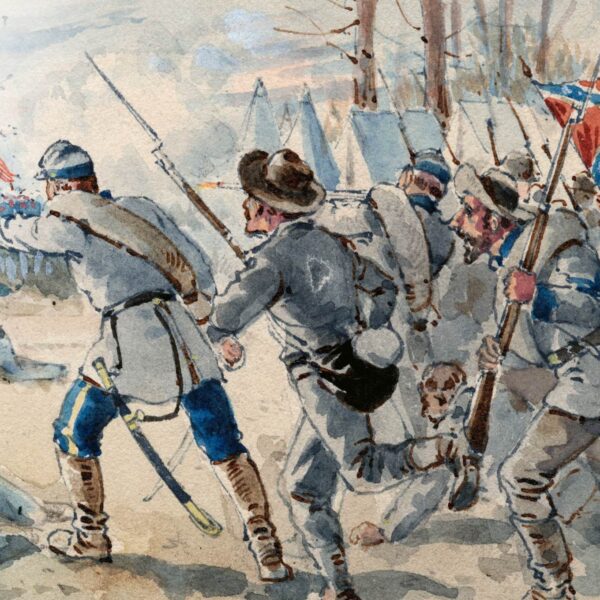

The virulent backlash against Confederate symbols and monuments and to the Lost Cause version of Civil War history is also a rejection of Civil War history that accords respect to the fighting men on both sides. Does this represent a fundamental assault on the traditional study of the Civil War?

We have been here before. Twenty years ago, the Civil War community was abuzz about the National Park Service’s mandate that battlefield parks’ interpretation must include slavery as a major cause of the war. Beyond the predictable charges of political correctness run amok, there was concern among traditional students of the war that the new policy would dilute battlefield parks’ original mandate to commemorate the actions of the men who fought and died on their grounds.

The world as we knew it did not end with this expanded interpretation of battlefield parks. In the years since, these parks have continued to educate visitors on the actions of the soldiers and leaders who fought the war—as well as the conflict’s causes and consequences—and scores of new books have appeared on its military aspects. There is nothing fundamentally incompatible between the study of Civil War military history and the critical evaluation of the war’s causes and consequences.

What might be different today is the breadth and depth of anger aimed at the Confederacy, Confederate symbols, and all perceived vestiges of Lost Cause thinking. That hostility is rife among not only activists but also scholars and public history professionals. Pent-up frustration over the stubborn grip of Lost Cause thinking seems to have produced a widespread willingness to vilify anything associated with the Confederacy as “racist.” Labeling is becoming a surrogate for understanding.

Scholars and professional public historians counsel a presentation of our country’s past that emphasizes inclusiveness, tolerance, empathy, and an acceptance of complexity. If they—we—live up to our own values, we will always include and empathize with people who want to understand all of the actors in the Civil War in the context of their times. If we do, we will retain the largest actual Civil War public history audience, one that does not need to be enticed or induced to be engaged with our subject.

John Coski is a seasonal veteran of the National Park Sevice and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and, since 1988, has worked for the Museum and White House of the Confederacy (now part of The American Civil War Museum) in Richmond, Virginia.

This article appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of The Civil War Monitor