Cadets from West Point take in the view of the battlefield from Little Round Top during a Gettysburg staff ride.

During any visit to Gettysburg National Battlefield Park it is not uncommon to encounter a group of military officers, noncommissioned officers, soldiers, or cadets huddled together, staring intently at the ground. They pore over maps, engage in long, animated discussions, and often scribble down notes. While casual visitors to the park take photos or read inscriptions on the multitude of striking unit monuments that dot the battlefield, these military groups immerse themselves in what they call the “staff ride,” a terrain-focused analysis of tactical decision-making and leadership. They examine not just what happened in the battle, but how and why it happened. And no other battle in American history provides more lessons for current military leaders than the one that occurred over three hot days in early July 1863.

In the 1980s, Michael Shaara’s landmark novel about the Battle of Gettysburg, The Killer Angels, could be found on almost any U.S. Army reading list, and commanders and their staffs began to put the pilgrimage to Gettysburg on the training calendar. Within a few years, it was hard to find an officer who had not visited the battlefield at least once. In 1987, the Army published a pamphlet entitled The Staff Ride, an official endorsement of what was already a popular practice within the officer corps. In the pamphlet’s forward, Gettysburg was said to “reflect valued principles for study by today’s leaders.”[1] Like the battlefield itself, these principles are timeless.

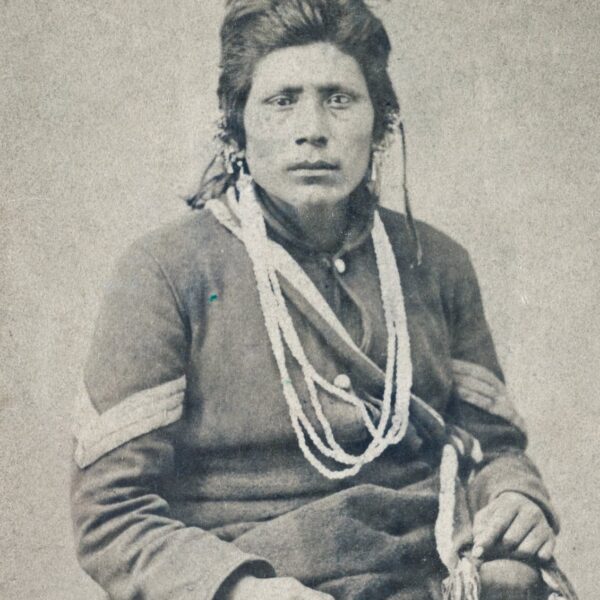

Union general John Buford

The lessons from Gettysburg are numerous, almost endless. There are, however, a number of themes and battlefield sites that seem to resonate with military groups. A common starting point for staff rides is near the statue of Major General John Reynolds to the west of town on the Chambersburg Pike. Looking westward out to Herr Ridge, groups can take in the terrain that lay before Brigadier General John Buford as he prepared to meet the first elements of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which was approaching along the pike early on the morning of July 1. Buford’s understanding of what was at stake, his choice of terrain, and his manner of employing his greatly outnumbered cavalry along the ridgelines made his performance a model of efficient tactical command. Buford’s desperate delaying action managed to hold off Major General Henry Heth’s Confederate brigades until Reynolds arrived with reinforcements from his I Corps.

Standing in the shadow of the Eternal Light Peace Memorial on Oak Hill and staring south toward Gettysburg, groups can contemplate the advance of Major General Richard Ewell’s Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia on the town during the afternoon of July 1. Here, they discuss the issues of commander’s intent and communication. Lee’s directive to Ewell earlier in the day to take Cemetery Hill “if practicable” resulted in the Confederates halting their advance short of the high ground, much to the dismay of some of Lee’s officers.[2] Should Ewell have seen the crucial importance of gaining Cemetery Ridge or Culp’s Hill and pressed the attack? Was Lee’s guidance too vague? Did Ewell miss a golden opportunity or make a sound judgment call? Such questions will never be answered fully, which is exactly why they are so valuable for military decision makers. Sifting through the arguments, examining the hypothetical, and engaging in counterfactual history are all useful exercises for conducting a critical analysis of Gettysburg and how it relates to battles in more modern conflicts.

There are few spots, if any, at Gettysburg that conjure martial mysticism like Little Round Top. Indeed, this rocky hill at the southern edge of the battlefield is perhaps the favorite stopping point of most military officers who visit the park. Why? Bravery. Initiative. Guts. The impressive defensive stand of the 20th Maine Infantry atop Little Round Top on the afternoon of July 2 and the steadfast leadership of its commander, the warrior-scholar

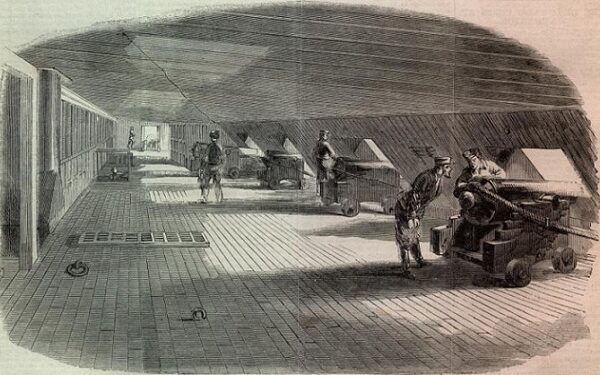

Timothy O’Sullivan took this image of Union breastworks on Little Round Top (with Big Round Top in the distance) shortly after the Battle of Gettysburg.

Colonel Joshua Chamberlain, have inspired generations of military thinkers. A short walk along the ridgetop leads to the statue of Brigadier General Gouverneur K. Warren and an ideal position to view the battlefield in its entirety. Here, staff ride groups contemplate the fish-hook-shaped defensive line established by the Union forces and debate the execution of Lee’s attack against its southern flank in the late afternoon of the battle’s second day. An almost unavoidable aspect of battle analysis is assigning fault or blame for tactical or operational failure. And from the vantage point on Little Round Top—with Devil’s Den, the Wheatfield, and the Peach Orchard in view—groups can picture battle scenes where there was no shortage of blame, but also great reason for commendation.

The final, culminating event in most military visits to Gettysburg starts at the Virginia Monument, in the shadow of a mounted Robert E. Lee staring out across the half-mile stretch of open ground that saw the ill-fated Confederate frontal attack on the battle’s third day, known to history as Pickett’s Charge. The view lends itself to bewilderment and head-scratching. What was Lee thinking? How could he have sent his army across an open field, completely exposed to enemy artillery fire, against a heavily fortified Federal line? Did the (successful) audacity he previously displayed during the Seven Days Battles and at Chancellorsville blind him to reality on July 3? Was Lee truly the tactical master that so many histories have made him out to be, or does the seemingly senseless, or even suicidal, order for the assault negate all those previous victories? And as groups make the long, almost ceremonial walk in the footsteps of Pickett’s and Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew’s divisions up to the rock wall marking the Union line, it is hard not to marvel at the tremendous task that was asked of soldiers from both sides that day. The scene serves as a permanent, sobering reminder that the boldest plan is not always the wisest.

It would be easier, perhaps, for military leaders to rely on books or films to teach lessons from past conflicts. But as Civil War historian Carol Reardon notes, historical memory is not always honest, and often incomplete.[3] Generations of military men and women have learned through personal experience that there is no substitute for walking the ground, seeing as best as possible what the original participants saw, and searching for the how and why. Undoubtedly, Gettysburg National Battlefield Park will remain a favorite location to continue that search for generations to come.

Clay Mountcastle, a retired U.S. Army officer, currently serves as director of the Virginia War Memorial in Richmond. He holds a Ph.D. in history from Duke University and is the author of Punitive War: Confederate Guerrillas and Union Reprisals (University Press of Kansas, 2009).

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2013 (Vol. 3, No. 2) issue of The Civil War Monitor.