THE LINCOLN AUTOPSY

Dr. Mathew W. Lively’s article about the autopsy of President Lincoln [“The Lincoln Autopsy,” Vol. 13, No. 2] was particularly interesting to me because the physician who performed the autopsy, Dr. Joseph Janvier Woodward, had treated my great-grandfather 3 1/2 years earlier, in October 1861.

My great-grandfather Andrew J. Speese was a trooper in Company H, 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. While patrolling from Mount Vernon toward Pohick Church, his company came under fire by Confederate infantry pickets at Accotink, Virginia. He was shot through the right thigh by a minie ball and taken to a military hospital near Fort Lyon, Virginia. The supervising physician there was Dr. J.J. Woodward, assistant surgeon, Company G, 2nd U.S. Artillery.

As a descendant, I can attest to the quality of care provided by Dr. Woodward. My great-grandfather recovered from his wound, spent six months as a flagman in the Signal Corps, then was able to return to his unit in the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, where he successfully completed his three-year enlistment.

Thank you, Dr. Woodward, and thank you, Dr. Lively, for an interesting article.

Andrew J. Speese

Kailua, Hawaii

LEE’S LETTERS

In his latest essay in the Monitor [“Voices from the Army of Northern Virginia, Part 7: Robert E. Lee,” Vol. 13, No. 2] Gary Gallagher’s emphasis on the final paragraph of a seven-paragraph letter General Robert E. Lee wrote to Confederate Secretary of War Seddon dated January 10, 1863, is misplaced. He tells us Lee’s comments about “a savage and brutal policy” that threatened “degradation worse than death” were a “visceral reaction” to the Emancipation Proclamation. While Gallagher gives the impression that Lee’s words were in response to Lincoln’s proclamation of freedom for enslaved Africans, it is plain that Lee was taking issue with Lincoln’s intent to put the freed Africans in uniform and send them out into the countryside as armed soldiers.

Similarly, Gallagher’s interpretation of Lee’s letter to his wife after the Battle of Gettysburg ignores the reality that, in fact, the Battle of Chancellorsville destroyed the Army of Northern Virginia’s chain of command, which Lee could not repair before being compelled, by circumstance, to begin the march to Gettysburg.

Finally, Gallagher pretends a misunderstanding of the paramount principle of American political science as the framers of the old constitution understood it when he makes the unsupported claim that the actual text of Lee’s letter to his brother Sidney Smith, dated April 20, 1861, was changed to read “secession” instead of “revolution”—as if Lee thought there was a difference. What is important in this letter is the political requirement that the people of Virginia ratify the ordinance of secession as an expression of their will that their state’s political connection to the Union be extinguished. Though the result of the war was the establishment of a new constitution, that fact does not change the political basis underpinning the old.

Joe Ryan

Los Angeles, California

Ed. Thanks for your letter, Joe. We asked Gary Gallagher if he cared to respond. He writes: “Regarding Mr. Ryan’s observations, I urge the Monitor’s readers to consult the documents and judge for themselves how best to interpret them. The comments regarding Lee’s letter of April 20, 1861, to his brother merit attention. Rather than an ‘unsupported claim,’ my statement rests on a comparison of the original letter and the version printed by Robert E. Lee Jr. in 1904. I did not suggest R.E. Lee changed the word ‘revolution’ to ‘secession’ but that his son did so. That change strongly suggests, contrary to Mr. Ryan’s assertion, that most people would find a significant difference between the two words.”

CRITICISMS

Recently some letters to the editor have complained about perspective and editorial changes in your magazine. Those complaints were blithely dismissed. I have a lot of thoughts about that, which I will keep to myself, but I will say that when I first subscribed to The Civil War Monitor over a decade ago, I never expected to read the word “intersexuality” in the magazine (Winter 2021, page 61).

Oren Johnson

Via email

Ed. Thanks for the note, Oren—and for your status as a longtime Monitor subscriber. It’s support from folks like you that has kept us going this long; please believe me when I say we’re grateful to you for it. As for the reader criticisms we’ve published in this space over the last several issues, I hope I haven’t “blithely dismissed” any of them. I can assure you that we value all our readers’ feedback—and not just the comments that make us feel good. That’s not to say we agree with every criticism, some of which simply don’t ring true or are clearly based on a falsehood. Case in point: your (implied) disapproval at reading the word “intersexuality” on page 61 in our Winter 2021 issue. I checked, and that word does not appear on that page (or on any other page in that issue). I imagine the word that caught your attention is “intertextuality,” which does appear on that page in the following sentence in Kathryn Shively’s comments about Stephen Cushman’s book The Generals’ Civil War, selected as her favorite Civil War title of 2021: “Similar to the reading experience of last year’s excellent Belles and Poets: Intertextuality in the Civil War Diaries of White Southern Women (Louisiana State University Press) by Julia Nitz, the reader may leave The Generals’ Civil War feeling uncomfortable about the hazy boundary between fiction and history.” (In its description of the book, LSU Press writes in part, “In Belles and Poets, Julia Nitz analyzes the Civil War diary writing of eight white women from the U.S. South, focusing specifically on how they made sense of the world around them through references to literary texts.”)

I take care in highlighting your error not to embarrass you, but rather to reinforce my earlier point—that not all criticisms we receive are grounded in fact. We sincerely hope that you stick with the Monitor—and that you’ll keep your comments, positive or otherwise, coming.

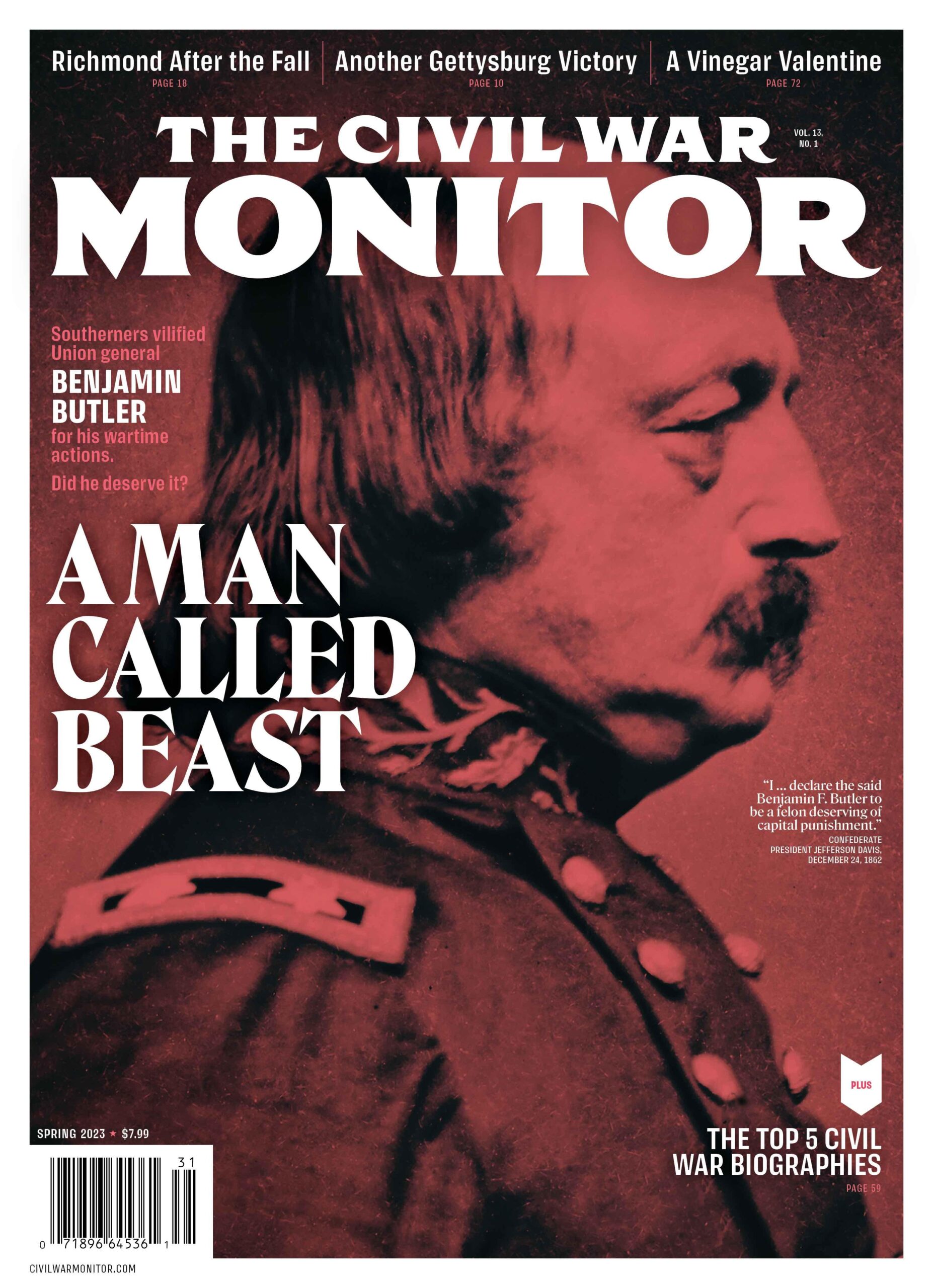

A BIT MORE ON BUTLER

In the “Dispatches” section of your Summer 2023 issue, reader Gary C. Kuncl, commenting on Elizabeth Leonard’s Spring 2023 article, “A Man Called Beast,” wondered why General Benjamin Butler didn’t simply arrest the offending women of New Orleans for “assaulting military personnel.” He apparently forgets that, besides spitting at Union soldiers, some women also emptied chamber pots on their heads. As a retired federal agent, I know what Butler’s motive was: deterrence. Being arrested for what Confederates considered “acts of resistance” would have made the women heroes and martyrs. Their sentences would have been light and they would have kept on doing it. Treating them as prostitutes, considered the lowest form of women back then, humiliated them and destroyed their hero status. I doubt the “outrage” his actions provoked made Confederates hate the North any more than they already did. By all accounts, the policy worked. Butler’s men likely cared little about the “terror visual” their commander created. In all probability morale improved because the assaults were drastically reduced and they knew their general had their backs.

Patrick B. Miano

Phoenix, Arizona

* * *

Thanks to Elizabeth Leonard for her fine article on Benjamin Butler! I cannot tell you how long I have waited for a fair, honest, and accurate history of Butler’s long and important service to his country. For far too long have southern revisionists polluted the name and character of this good man. And all too many “historians” have been content to allow the slander to continue unchallenged as they apparently felt Butler was unworthy of their talented consideration. Well done, and I for one hope she turns her unprejudiced eye on some other Civil War generals who have been mugged by history.

William Paris

Via email

* * *

Elizabeth D. Leonard’s article about Union general Benjamin Butler is a compelling narrative. He was excessively vilified. While making a number of his failings clear, she also gives credit where credit is due. His support for women’s suffrage and rights; his dedication to pressing for economic and labor policies designed to lift working people and the poor; his work to ensure that black veterans received the pensions they were due for their military service; his efforts to desegregate the U.S. military service; and his efforts to desegregate the U.S. Military Academy by nominating young black men to West Point cadetships in hopes of reshaping the officer class in the regular army should help to mitigate any unnecessary vilification of General Butler.

Neil Dworkin

Naples, Florida

Kudos

I wanted to thank you and your staff for the color, character, and depth you and your writers bring to telling the story of the American Civil War. I enjoy every issue I receive; they have all painted a different perspective, many times from eyewitness accounts. Furthermore, the richness of character your writers employ to tell the story of the Civil War—without bias and without writing like a technical manual of history—helps me to step back and see the whole painting, not just the brush strokes. The richness of information makes me hungry to devour more.

Theodore E. Wojciechowski

Clearwater, Florida

QUESTION FROM A READER

If Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson had not been mortally wounded at Chancellorsville—and still had command of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Second Corps, as opposed to Richard Ewell getting it—would the Battle of Gettysburg have gone differently (especially concerning the first day’s fighting)? I would like to get your input.

Rick Heyer

Via email

Ed. OK, readers. What are your thoughts on Rick’s question? Let us know at [email protected]—but please keep your answers brief. We’ll look to publish some of them in our next issue.