Who were the Civil War’s biggest celebrities? We assembled a group of historians and asked for their picks. They could define “celebrity” as they saw fit, but with our guidance: Nominees might be submitted not only for what they had done (or were doing), but also for what they represented; their celebrity could have something, or nothing, to do with the war itself; and having been talked about regularly in the press—or having a wide readership or following—was to be considered key. Most important: High-ranking political and military figures were excluded. We present the group’s top 20 picks, ranked in order of popularity.

20. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.

A Medical and Literary Titan

While we are more familiar today with his soldier-jurist son, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. was the family’s celebrity in the mid-19th century. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1809, Holmes established himself both as a forward-thinking physician—he was an early advocate for the stethoscope and, in 1846, coined the word “anaesthesia”—and a celebrated poet and essayist. In 1856, Holmes helped found (and name) The Atlantic Monthly magazine in which many of his essays—most famously his “The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table” series in which he detailed life in a fictional New England boardinghouse—became some of the publication’s most popular features. (When it was published in book form in 1858, The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table reportedly sold 10,000 copies in its first three days.) Holmes’ personal essays on the war became iconic, including “My Hunt After the Captain,” describing his search for his son Oliver Jr., an officer in the 20th Massachusetts Infantry who had been wounded at Antietam. Holmes Sr. died in Boston in 1894 at 85.

19. Jenny Lind

The Swedish Nightingale

By the time she accepted P.T. Barnum’s 1850 invitation to tour the United States, Johanna Maria “Jenny” Lind had, at 29, established herself in her native Sweden and across Europe as a wildly popular opera singer and actress who dazzled her audiences. During her year and a half in America, Lind performed 150 concerts around the country, the first 93 for Barnum before continuing under her own management. She donated her profits (Lind’s concerts for Barnum earned her approximately $350,000, or nearly $15 million today) to various charities in Sweden and the United States. An obsession with her—termed “Lindomania”—quickly gripped the country, prompting her eager fans to snatch up a variety of Lind-related products, from photos to commemorative knickknacks. Among Lind’s many American admirers was poet Emily Dickinson, who wrote of the star: “Herself and not her music was what we seemed to love—she has an air of exile in her mild blue eyes, and a something sweet and touching in her native accent….” Even after her return to Europe, she remained a subject of interest here, with newspapers throughout the American Civil War frequently reporting on her concerts. She spent her final years in England teaching singing at the Royal College of Music, and died in Herefordshire in 1887 at 67.

18. Clara Barton

The Angel of the Battlefield

Clara Barton, a schoolteacher born in North Oxford, Massachusetts, began attracting national press during the war’s second year. Leaving teaching, Barton had relocated from New Jersey to Washington, D.C., in 1855, and had taken up nursing, starting with tending to soldiers wounded in Baltimore’s Pratt Street Riots in April 1861, the year she turned 40. After the Battle of Bull Run, she worked to gather supplies for the wounded; in 1862, after securing official permission to work at the front lines, she started distributing supplies herself, and reports on her efforts made the newspapers. Barton dressed wounds, served food, read to and wrote letters for patients—anything she could do to alleviate the suffering of both Union and Confederate soldiers wounded in many of the eastern theater’s bloodiest battles. She was determined to maintain a presence at the front (in one instance, a bullet tore through her dress and killed a man she was treating). “I may be compelled to face danger,” she later reflected, “but never fear it, and while our soldiers can stand and fight, I can stand and feed and nurse them.” By 1865, Barton’s name had become synonymous with Civil War nursing. Her fame grew after the war when she led a comprehensive, four-year search for missing (and presumed dead) soldiers, 22,000 of whose fates she helped determine for their families. She died in 1912 in Glen Echo, Maryland, at 90.

17. Kate Chase

Washington’s “It Girl”

Chase was an immensely popular Washington socialite during the war, when her father, Salmon P. Chase, served as secretary of the Treasury before being elevated to chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. The highly educated young beauty—she was 20 when Fort Sumter fell—served as her widowed father’s hostess, throwing parties in their Washington home at which she charmed both military leaders and Washington powerbrokers, all with the aim of advancing her father’s political ambitions. (He had been a founder of the Republican Party and considered challenging Lincoln for the party’s presidential nomination in 1864.) Among Kate’s many admirers was Union general Carl Schurz, who noted of her, “[A]ll her movements possessed an exquisite natural charm. No wonder that she came to be admired as a great beauty and broke many hearts.” Reports of Chase’s parties, fashion, and romantic relationships were covered in newspapers around the country. At her 1863 marriage to William Sprague, the wealthy governor of Rhode Island, the U.S. Marine band played, with President Lincoln in attendance. After her death in Washington in 1899 at 58, by then long divorced and a near recluse, The New York Times reflected on her wartime allure, noting that “the homage of the most eminent men in the country was hers.”

16. Robert Anderson

The Hero of Fort Sumter

In the runup to the war, Major Robert Anderson catapulted to prominence as the embattled commander of the tiny Union garrison at Fort Sumter. Though forced to surrender after a 34-hour Confederate bombardment in mid-April 1861, Anderson’s actions in defense of the isolated bastion had made him the first great northern hero of the conflict—someone who embodied the emerging determination to preserve the Union from the existential threat of secession. Days later, Anderson brought Sumter’s 33-star U.S. flag to a massive patriotic rally in New York City’s Union Square, where he was feted by a crowd estimated at 100,000. The fact that Anderson’s career fizzled—he was promoted to brigadier general in May and given command of Union forces in his home state Kentucky, an assignment that lasted only a few months before his removal and reassignment to Rhode Island—didn’t diminish his popularity as a symbol of the Union. In April 1865, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton invited Anderson, who had retired from the army in 1863, to attend a celebration of the war’s end at Fort Sumter, where he raised the American flag he had lowered at the 1861 surrender. He died in 1871 at 66 in Nice, France, where he had gone for his health.

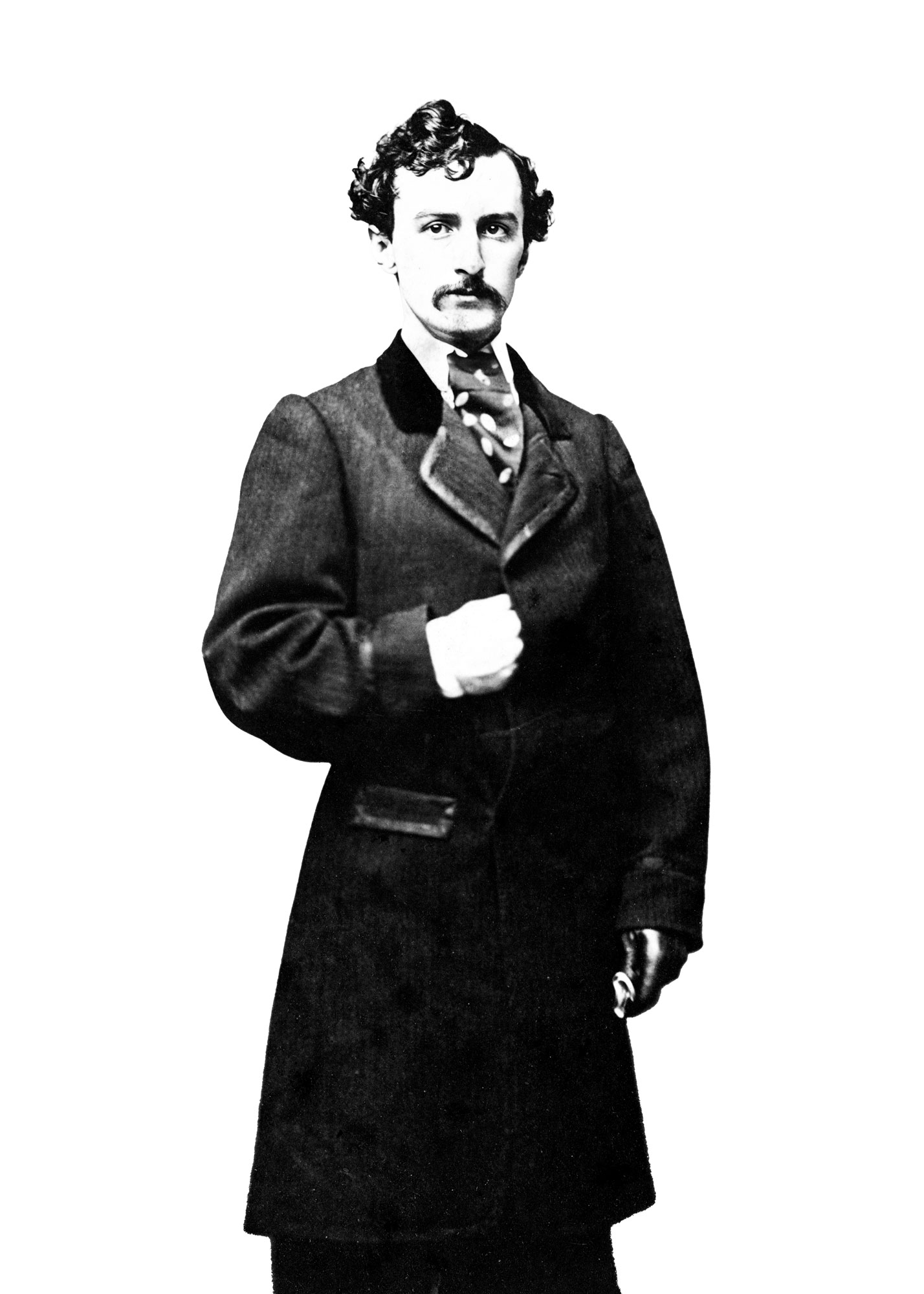

15. John Wilkes Booth

The Actor Turned Assassin

The youngest of three brothers in the nation’s most celebrated family of thespians, John Wilkes Booth made his stage debut in 1855 at 17 and rose steadily in reputation during the war. His athletic good looks—one reporter described Booth’s “stout and muscular” legs, “arms as white as alabaster, but hard as marble,” and “fine Doric face” framed by “a weight of curling jetty hair, like a rich Corinthian capital”—impressed audiences. He continued to perform throughout the North during the war, even as his pro-Confederate views became increasingly strident. In 1863, on tour in St. Louis, Booth was arrested for declaring that he “wished the President and the whole damned government would go to hell,” securing his release after paying a fine and taking an oath of allegiance to the Union. Two years later, Booth’s assassination of that president launched him to universal fame. “All honor to J. Wilkes Booth,” wrote a Louisiana woman speaking for many Confederates, “who has rid the world of a tyrant and made himself famous for generations.” In the North, most public opinion aligned with the newspaper that cheered Booth’s capture and death, writing that “such carrion only infects the earth and makes noisome stench throughout the moral atmosphere.” Booth was 26 when he died—11 days after Lincoln—near Port Royal, Virginia, from a Union soldier’s gunshot.

14. Belle Boyd

The Rebel Spy

The eldest child of a prominent Virginia family, Maria Isabella Boyd was an educated, beautiful, and bold 17-year-old living in the Shenandoah Valley in May 1861 when her father enlisted in the 2nd Virginia Infantry, part of a brigade commanded by Confederate general Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Before long, “Belle” was deployed by Jackson as a courier, carrying information, supplies, and weapons across enemy lines, efforts that were especially appreciated during Jackson’s successful Shenandoah Valley Campaign in 1862. Though captured and imprisoned several times by Union military authorities, she was undeterred in her efforts to aid the Confederacy, including ready in 1864 to board a ship bound for England armed with secret Confederate dispatches, only to be thwarted by the Union blockade. Along the way, Boyd’s fame (or notoriety) swelled, with newspapers from New York to California, and as far away as Australia, publishing breathless accounts of “Belle’s” exploits and multiple arrests—and, perhaps not surprisingly for a woman in the public eye, rarely failing to comment on her appearance. After the war, Boyd published a narrative of her experiences as a spy. She died in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin, in 1900 at 56.

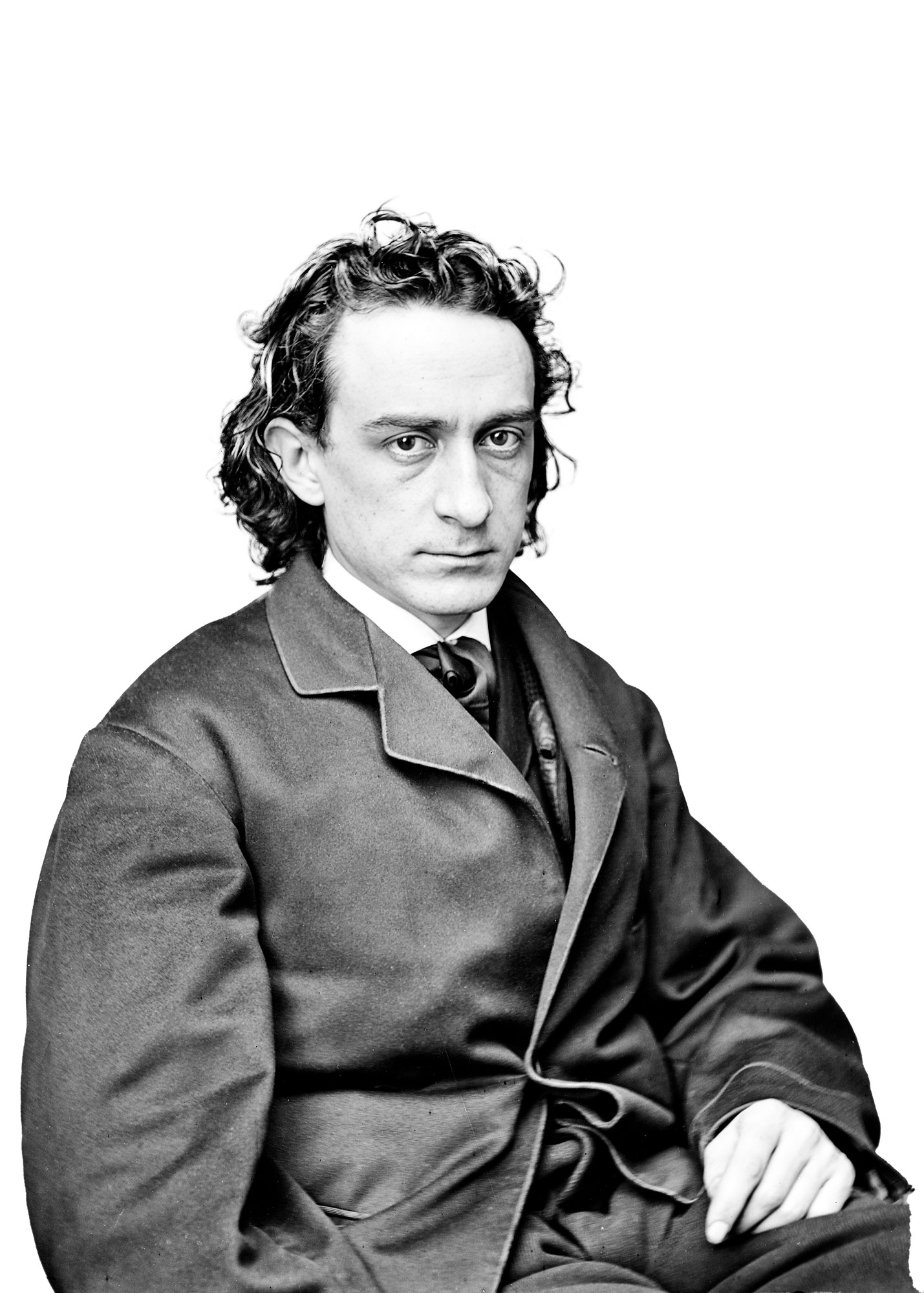

13. Edwin Booth

A Master Thespian

Today, Edwin Booth is best known—if he’s remembered at all—as the older brother of assassin John Wilkes Booth. Around the Civil War era, however, Edwin was by far the more successful and well-known actor in the family and considered by many to be the greatest American actor of his generation. Born in Bel Air, Maryland, in 1833, Edwin made his stage debut at 15; three years later, he undertook a worldwide tour, traveling as far as Australia. He continued to act during the war, with newspapers from Massachusetts to California advertising and reviewing the plays in which he inevitably had a starring role. In 1864, he appeared alongside siblings John Wilkes and Junius Brutus Jr. in a benefit performance of Julius Caesar—the only occasion the three actor-brothers appeared on stage together. (The money raised was used to erect a statue of Shakespeare that still stands in New York’s Central Park.) Edwin, an avowed Unionist, disowned his brother after Lincoln’s murder and amid the tarnishing of the family name took a brief hiatus. But he returned to the stage and in 1869 opened his own theater in New York, where he died in 1893 at 59.

12. Clement Vallandigham

The Antiwar Agitator

Clement Vallandigham’s claim to fame—or notoriety—was as leader of the northern Peace Democrats (the so-called “Copperheads”) during the Civil War. A strident critic of President Lincoln’s administration, Vallandigham, a U.S. Representative from Ohio, came to symbolize militant and partisan opposition to the Union war effort. His dramatic speeches and antiwar activities kept his name in newspapers North and South, as did his May 1863 arrest and trial for defying Union general Ambrose Burnside’s orders seeking to subdue disloyal speech and acts in the Department of Ohio. After his conviction, Vallandigham was banished to the Confederacy before he relocated to Canada. When he reappeared in the United States in 1864 to play a prominent role in the Democratic presidential convention in Chicago, where he pushed for the party platform’s “peace plank,” Lincoln chose to ignore him rather than make him a political martyr once more. After the war, Vallandigham went home to Ohio, where he lost several bids to return to Congress. He was 50 when he died in Lebanon, Ohio, in 1871, after accidentally shooting himself in the abdomen with a pistol.

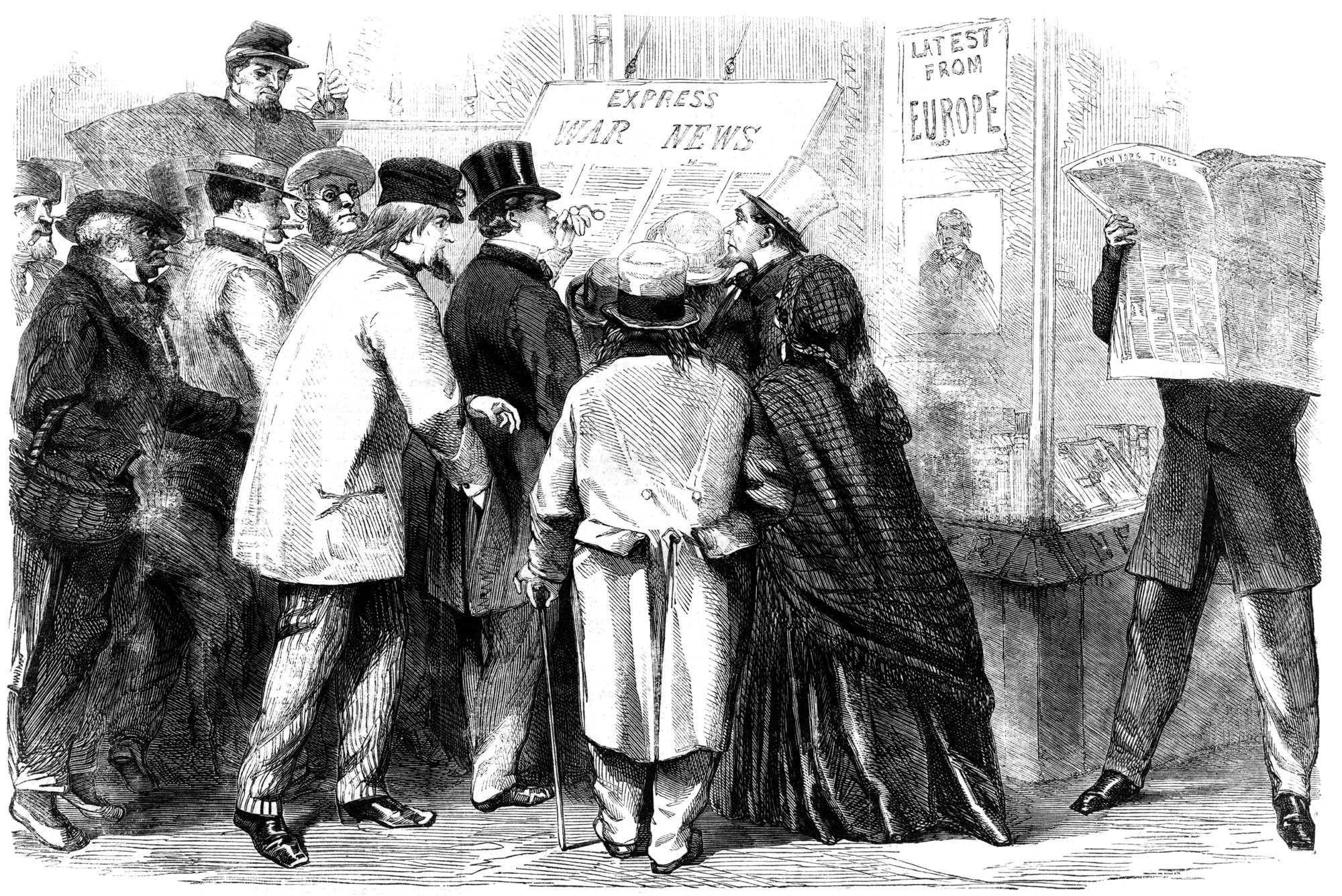

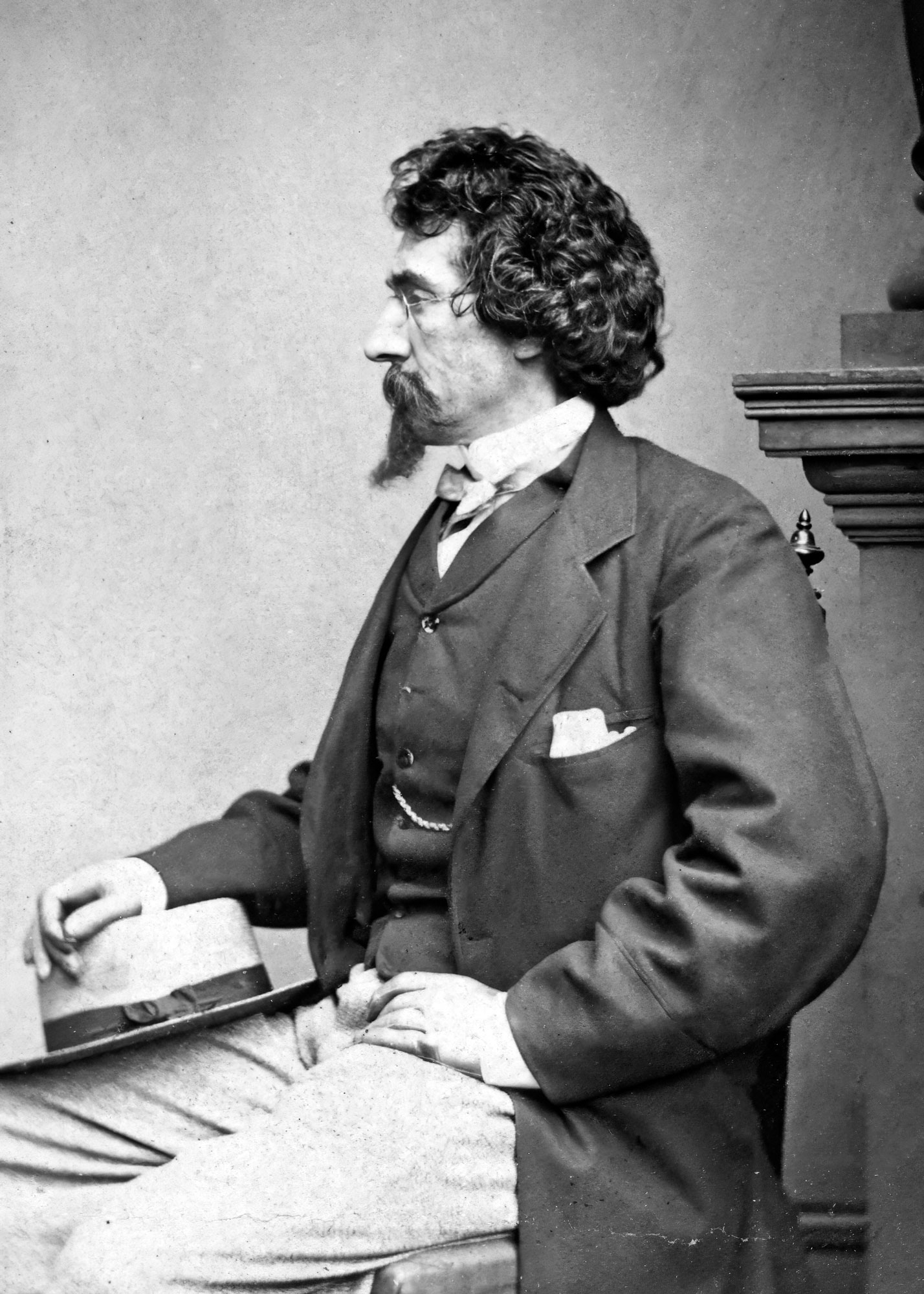

11. Mathew Brady

The Celebrity Photographer

Arguably no unelected noncombatant did more to immortalize the battles and leaders of the Civil War than Mathew Brady. He was already celebrated before the war as the leading American portraitist, nearly as famous as many of his prominent subjects. His New York photography studio was a place where visitors could browse his “Gallery of Illustrious Americans”—large images of celebrated politicians, generals, actors, and authors—and pose for an image they could share as small cartes de visite to be saved in the photo albums of family and friends. During the war, Brady, donning his distinctive spectacles and white hat, left the comfort of his studio to photograph fields of action and battlefields. As his vision declined, he sent talented subordinates such as Alexander Gardner to work in his stead. In 1862, his exhibition of photos of soldiers killed at the Battle of Antietam shocked the nation, allowing civilians to experience the conflict as never before. Perhaps inevitably after the war, interest in his battleground images declined, and Brady was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1873. He died penniless in New York in 1896 in his early 70s.

10. Anna Dickinson

The Girl Orator

Born in 1842 to working-class Philadelphia Quakers, Anna Dickinson rose to local fame in her teens as a fiery orator speaking for women’s rights, abolition, and temperance. During the war’s first year, she attracted the attention of nationally known reformers such as Lucretia Mott and William Lloyd Garrison, both of whom arranged speaking tours for her. Of her speaking style, admirer Mark Twain noted, “She talks fast, uses no notes what ever, never hesitates for a word, always gets the right word in the right place, and has the most perfect confidence in herself…. [She] would compel the respect and the attention of an audience, even if she spoke in Chinese….” (Or, as one of our historian panelists remarked, “If Anna Dickinson was alive today, she would have her own nightly program on cable news.”) In 1863, Senate Republicans facing reelection that fall enlisted the staunch Unionist to deliver campaign speeches up and down the East Coast with which she swayed voters to the Republican cause. In 1864, she became the first woman to deliver a speech on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, which elicited a standing ovation (including from Abraham and Mary Lincoln, who were in attendance). When Dickinson’s fame subsided in the 1870s, she famously mountaineered in Colorado and then turned to writing plays and some acting. She died in Goshen, New York, in 1932 at 89.

9. George Armstrong Custer

The Boy General

If Robert Anderson was an old-fashioned, “old army” representative of patriotism, George Armstrong Custer personified the fast-track rise to fame that courage and “dash” could create. Born in New Rumley, Ohio, in 1839, Custer was already a colorful and controversial figure in his West Point years (he graduated in 1861, last in his class). He went on to demonstrate impressive military skills, superb horsemanship, and charismatic leadership at several notable cavalry battles, including at Gettysburg and during the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. He became a favorite of the press as well as of several influential commanders, among them Alfred Pleasonton and Philip H. Sheridan, relationships that helped propel him through the ranks—and secure his promotion to brigadier general at only 23. Custer’s carefully cultivated personal appearance attracted as much attention as his battlefield risk-taking: His colorful nickname, “Cinnamon,” referred to his use of scented hair oil on his long golden curls; his distinctive black velvet uniform trimmed with gold lace led one of his staff to describe the young warrior as looking “like a circus rider gone mad.” Custer’s postwar career ended disastrously in Montana Territory at the Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25, 1876. Even then, his dramatic death at 36, rather than tarnishing his celebrity, gilded it with tragic romance.

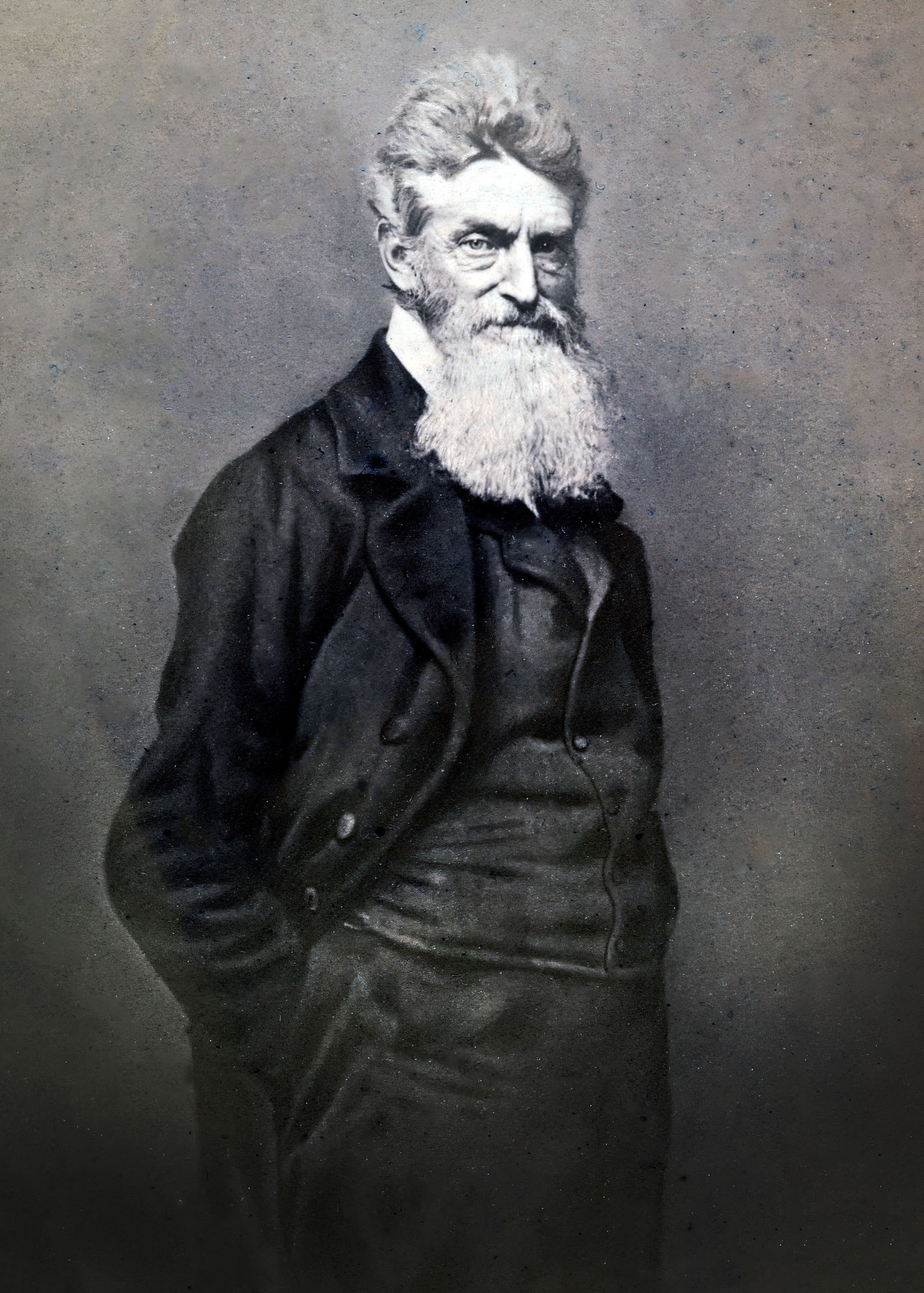

8. John Brown

The Holy Insurrectionist

On December 2, 1859—before he was hanged for treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia for his failed bloody raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry to secure arms for an intended slave insurrection—John Brown spoke prescient final words. He was, he said, “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” Born in Torrington, Connecticut, in 1800, Brown had spent his life agitating—often violently—against the institution of slavery and its supporters, earning a reputation during the antebellum struggles in “Bloody Kansas” and elsewhere for being brave bordering on fanatical. Coverage of Brown’s raid, trial, and execution in Charles Town that day, at age 59, made him an international celebrity. In America, the reaction was mixed: Those who sympathized with the abolitionist cause revered him as a martyr, while southerners cited him as the most dangerous example of northern antislavery activism. During the war he may have foreseen, Brown’s celebrity in the North grew; the song “John Brown’s Body” became popular among Union soldiers, its familiar lines (“John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave, His soul’s marching on”) regularly heard on the march.

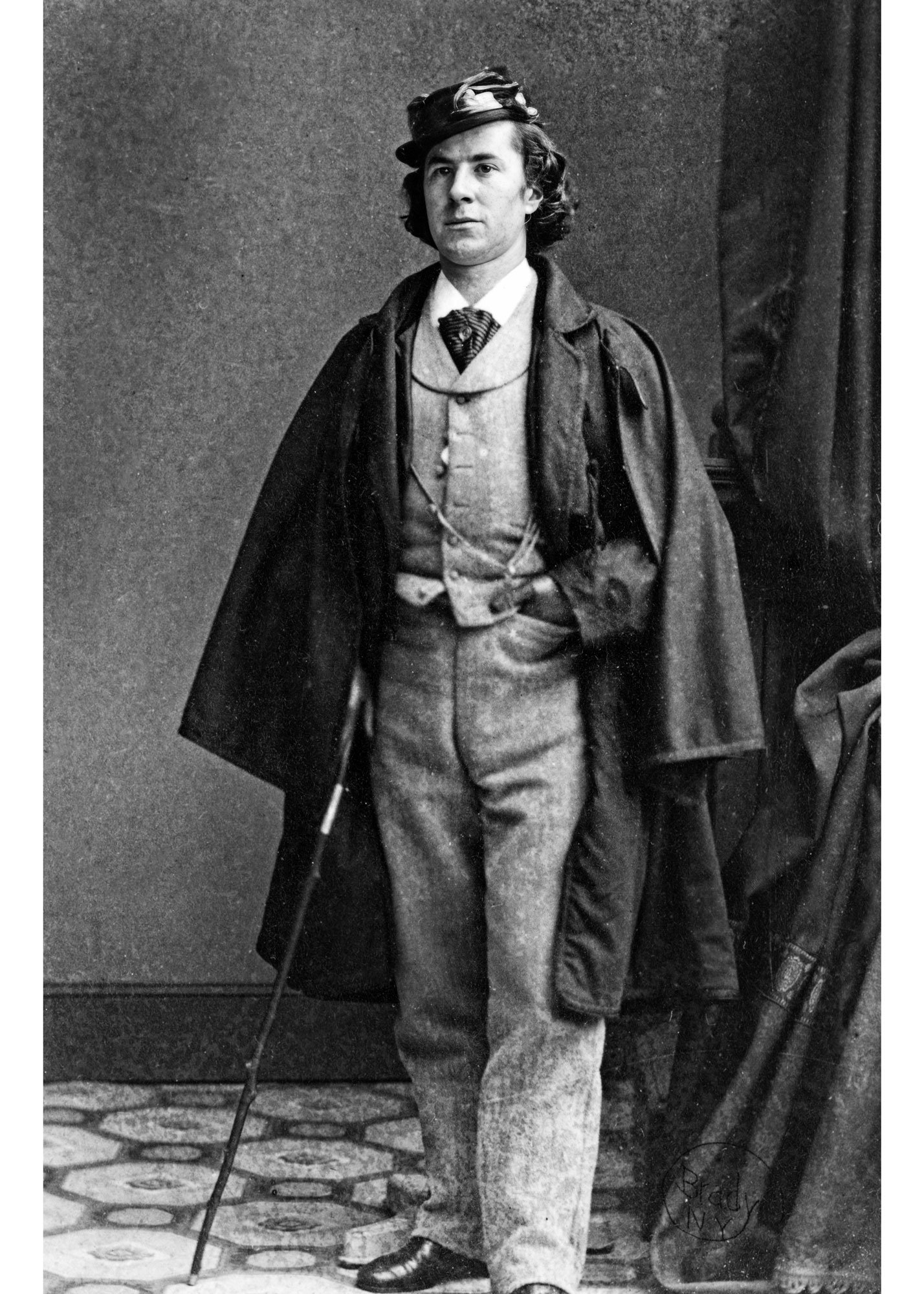

7. Elmer Ellsworth

The Union’s First Martyr

Elmer Ellsworth, born in 1837 in Malta, New York, achieved national renown in the summer of 1860 when he and his colorfully uniformed military drill team, the “Zouave Cadets of Chicago,” dazzled crowds with their athleticism and esprit de corps on their wildly popular tour of northern cities. Responding the next year to President Lincoln’s war call for volunteers, Ellsworth raised and assumed command of the 11th New York Infantry “Fire Zouaves” in New York City, leading them to the defense of the capital, their every move reported on by the press. After the young colonel was killed on May 24 in Alexandria, Virginia, while removing a Confederate flag from the roof of a hotel owned by a Confederate sympathizer, the nation mourned his loss. Northerners took up the cry “Remember Ellsworth”; Union regiments were named in his honor; and his visage was printed on an array of patriotic stationery and keepsakes. Lincoln, a personal friend (Ellsworth had clerked at his law office in Illinois before the war), ordered his body laid in state at the White House. In a letter to Ellsworth’s parents on May 25, the president noted how deeply he felt their grief, in a sentiment countless northerners shared: “In the untimely loss of your noble son, our affliction here, is scarcely less than your own.”

6. Charles Sherwood Stratton

The Diminutive Star

Charles Stratton became a huge celebrity before and then during the Civil War era through the tireless promotion of showman P.T. Barnum. Stratton was born in 1838 in Bridgeport, Connecticut, with what would be called dwarfism, and introduced to Barnum as a child, he performed as “General Tom Thumb,” enchanting audiences worldwide in the carnivalesque atmosphere of Barnum’s traveling shows. His celebrity status peaked in 1863 when, at 25, he married Lavinia Warren, also born with dwarfism, in a spectacular wedding orchestrated by Barnum at Grace Episcopal Church in New York City. Thousands of people visited Barnum’s American Museum to meet Stratton and Warren in the days leading up to the wedding, which was front-page news (the Chicago Tribune gave it two full columns)—evidence that, even amid the endless bloodshed of the war, Americans were fascinated by celebrity culture. President and Mrs. Lincoln even threw a White House reception in the couple’s honor during their honeymoon. Stratton’s association with Barnum made him a wealthy man. In 1883, when he died of a stroke at 45 in Bridgeport, some 20,000 admirers attended his funeral.

5. Henry Ward Beecher

America’s Preacher

Along with his siblings (including older sister Harriet Beecher Stowe), Henry Ward Beecher was a member of one of America’s most illustrious 19th-century families. The son of prominent Calvinist minister and evangelist Lyman Beecher, Henry was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, in 1813. In his mid 30s, he became the first pastor of Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York. Before long he was a nationally celebrated religious leader, ministering to his large congregation and traveling the country as a popular orator, his optimistic and open-minded sermons often championing reformist causes such black freedom, votes for women, temperance, and evolution. By 1860, Beecher was so famous that presidential aspirant Abraham Lincoln made sure to worship at his church both before and after delivering his Cooper Union address that February. As president, Lincoln would call on Beecher at key moments during the war, dispatching him to Europe in 1863 to raise support for the Union and, at war’s end, to Fort Sumter to speak at the momentous ceremony at which the U.S. flag was raised over the recaptured bastion. “We had better send Beecher down to deliver the address,” Lincoln noted, “because if it had not been for Beecher there would have been no flag to raise.” Beecher—who was hounded after the war by accusations of adultery—died in New York in 1887 at 73.

4. Phineas Taylor “P.T.” Barnum

The Master Showman

The Civil War era had no greater self-promoter than Phineas Taylor Barnum. Born in Bethel, Connecticut, in 1810, young Barnum ran several businesses and founded a newspaper before relocating to New York City in 1834. There his wildly successful career as an entertainer began. In 1841, he opened Barnum’s American Museum on Broadway where, over the ensuing decades, his unique brand of bravado and hokum captured the American imagination. The five-story building—a combination lecture hall, theater, zoo, aquarium, and museum—advertised a vast (and constantly changing) array of attractions, among them plays, wax figures, minstrel shows, dioramas, and taxidermy exhibits. There were as well a variety of such absurdities as the Fiji Mermaid, a mummified monkey’s torso with a fish’s tail attached, and “living curiosities,” including conjoined twins Chang and Eng and the so-called giantess Anna Swan. Over its 24 years in existence, an estimated 38 million Americans paid the museum’s 25-cent admission to feast on its diversions. Interest did not wane during the war years, when Barnum’s particular brand of entertainment seemed just what a public tired by the war’s endless bloodshed and upheaval required. In November 1864, Barnum’s pro-Union sympathies inspired a Confederate sympathizer to try (and fail) to burn the museum; the following summer, a fire of unknown origin gutted the structure. He established it at another location, which also was destroyed by fire in 1868, after which Barnum retired from the museum business. He died in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in 1891 at 80.

3. Harriet Beecher Stowe

The Lightning-Rod Novelist

Born in 1811, the sixth of 11 children in the prominent Beecher family of Litchfield, Connecticut, Harriet Beecher Stowe arguably achieved more fame—and wielded greater influence—than her preacher father or any of her famous siblings. At a time when the power of the press influenced how Americans understood the issues at the heart of the burgeoning sectional crisis, and made writers into well-known names and opinionators, Stowe published her debut novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in 1852. It became an instant international sensation. The heart-wrenching tale about the brutality of American slavery and the agency and Christian morality of African Americans trying to resist oppression sold some 300,000 copies in the year after its publication. It went on to become the second best-selling book of the century in America, behind only the Bible, and gained a still larger audience after it was adapted by playwrights for theatrical productions. Though Abraham Lincoln’s quip that Stowe was “the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war” is apocryphal, her novel undeniably fueled the heated American debate over slavery that culminated in conflict. Stowe authored a total of 30 titles before her death at 85 in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1896.

2. Horace Greeley

The Media Mogul

By the start of the Civil War, Horace Greeley had cemented his status as the most famous and influential newspaper editor of his day. Born in 1811 in Amherst, New Hampshire, by 1841, he had founded the New-York Tribune—its New York City offices situated just blocks away from Mathew Brady’s and P.T. Barnum’s establishments—which he built into the nation’s largest newspaper, with a circulation of nearly 300,000 in 1860. In his career as the paper’s eccentric and opinionated leader, Greeley earned a loyal readership and rabid opposition, and his name and instantly recognizable likeness (pale face, bald dome, wispy beard, thick glasses) appeared often in political cartoons that condemned his reformist and radical ideas, including socialism, vegetarianism, spiritualism, pacifism, and abolition. During the war, Greeley used his power and platform (his Tribune editorials were widely copied in other Republican newspapers) to influence the direction of the conflict: In the summer of 1861, for instance, his urging of northern forces “on to Richmond” helped precipitate the Union advance that ended in defeat at Bull Run; a year later, his “Prayer of Twenty Millions” editorial not only pressured President Abraham Lincoln to take action on emancipation but also provided him cover to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Simply put, Greeley could claim to be one of the principal shapers of public opinion during the Civil War, constantly challenging politicians and army officers to justify their decisions to the American people. (As one of our historian panelists put it, Greeley was “Sean Hannity, Rachel Maddow, and Joe Rogan rolled into one.”) He died at 61, in Pleasantville, New York, in November 1872, shortly after his wife’s death and his failed run as the Liberal Republican Party candidate for president against Ulysses S. Grant.

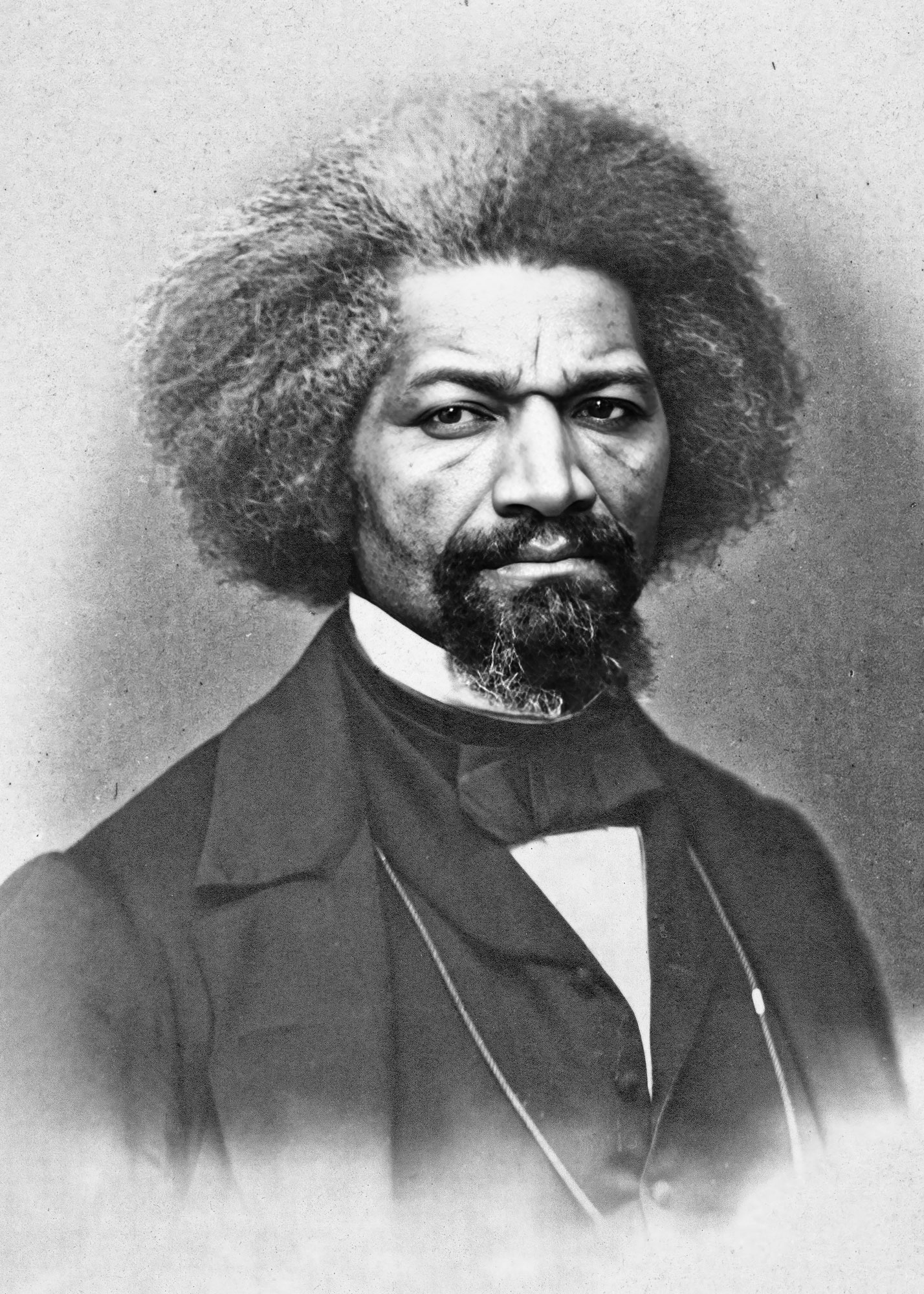

1. Frederick Douglass

The Legendary Abolitionist

Born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in 1818, Frederick Douglass escaped to freedom two decades later and went on to craft an extraordinary public life as an orator, author, journal editor, and campaigner for emancipation and equal rights. During the 1840s and 1850s, he published two bestselling autobiographies (a third appeared in the 1880s) and lectured widely and passionately for the abolitionist cause, his intellect and eloquence challenging many Americans’ long-held notions of black inferiority. By the outbreak of the Civil War, Douglass had become a household name across the county; he’s thought to have been the most photographed American in the 19th century, his image adorning countless homes and churches, white and black alike. As the conflict ground on, Douglass leveraged his reputation and power to press the administration for the inclusion of abolition as a war aim; breaking all racial precedents, he conferred with President Lincoln at the White House on at least three occasions. After the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, which authorized black military enlistment, Douglass turned tireless recruiter, helping persuade thousands of African Americans (including two of his sons) to join the Union forces—then agitating for them to receive the same pay as their white comrades. All the while, Douglass continued to receive enormous mainstream press coverage. He remained in the public eye after the war, continuing his advocacy for equality.

He died in Washington, D.C., in 1895 at 76 or 77.

Contributors:

Stephen Berry, Matthew Christopher Hulbert, Carolyn Janney, Brian Luskey, Gary W. Gallagher, J. Matthew Gallman, Hilary Green, Sarah Handley-Cousins, Harold Holzer, Andrew F. Lang, Anne E. Marshall, James Marten, Megan Kate Nelson, Kenneth W. Noe, Jason Phillips, George Rable, Brooks D. Simpson, Amy Murrell Taylor, Joan Waugh, and Cecily Zander.