National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution (colorized by Patrick & Dylan Brennan)

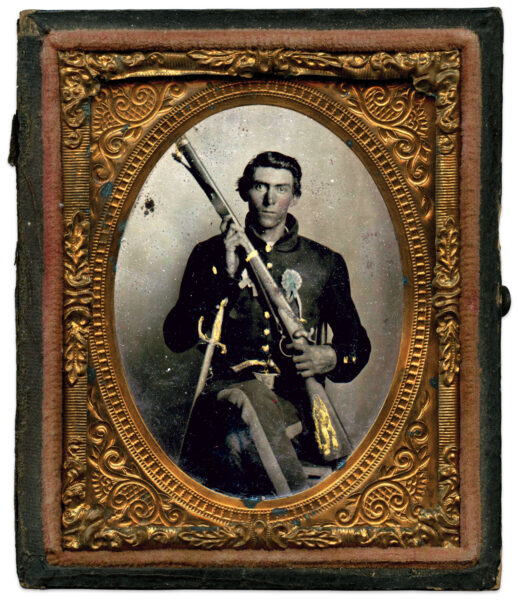

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution (colorized by Patrick & Dylan Brennan)By 1861, Elmer Ellsworth had become a household name in much of America.

On May 25, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln wrote the grieving parents of Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth a tribute to their “noble son” who, at 24, had died the day before, shot to death by an irate secessionist in Alexandria, Virginia. “My acquaintance with him,” Lincoln recounted, “began less than two years ago; yet through the latter half of the intervening period, it was as intimate as the disparity of our ages, and my engrossing engagements, would permit.” Lincoln judged the slain soldier’s “power to command men” was “surpassingly great.”1

Witnesses recounted Lincoln grief-stricken, bursting into tears, and struggling to keep his composure. Upon viewing Ellsworth’s body, the president exclaimed: “My boy! My boy! Was it necessary this sacrifice should be!”2 To honor the loss, Lincoln ordered Ellsworth’s body to lie in state in the East Room of the White House.

The American Civil War had barely begun, but Ellsworth’s shocking death clearly struck a chord, not just with the new president, but across the Union.

Already Ellsworth was famous—a self-taught drill master and military aficionado, he had gained national attention the summer before with his touring Chicago Zouaves, who thrilled audiences with their synchronized drills, gymnastic feats, and colorful uniforms, and created what one newspaper proclaimed “Zouave on the brain.”3 Ellsworth’s acquaintance with Lincoln and dramatic death sealed his celebrity, making him, for a time, “the most talked-of man in the country.”4

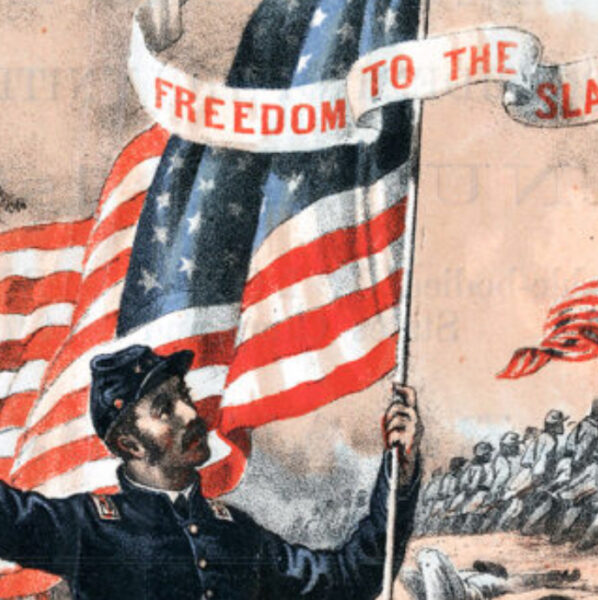

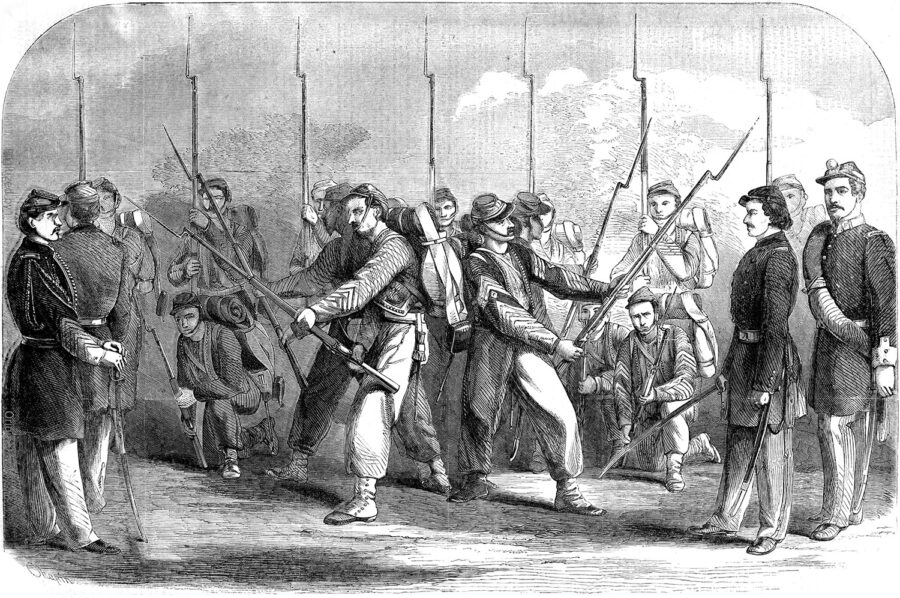

The Huntington Library, San Marino, California

The Huntington Library, San Marino, CaliforniaBy the time of his death in May 1861, Elmer Ellsworth—a self-taught drillmaster and military aficionado—had earned national fame touring with his Chicago Zouaves, who captivated audiences with their synchronized drills, gymnastic feats, and (as shown in this illustration from 1860) colorful uniforms.

Lincoln’s and Ellsworth’s biographers have deemed the relationship genuine, with the two men drawn to each other through luck and circumstance. In 1860, Ellsworth had put aside his military dreams to seek more respectable employment as a law clerk in Lincoln’s office. By then, Lincoln was catapulting to political prominence with the newly founded Republican Party and election as president. Ellsworth, 23, was a striver—charismatic and ambitious—and perhaps Lincoln, 51, recognized something of himself in the younger man. They contrasted, too, in their appearance: Lincoln was tall, gaunt, and a bit awkward; Ellsworth was short, athletic, and always dapper. Historians have called their relationship special and close, one likening it to a “school-boyish crush.”5

But their friendship had its limits. As the nation moved inexorably toward war, Lincoln took time to try to help Ellsworth advance with a scheme to revise the country’s militia system, testing both well-established military protocols and the boundaries of his position as commander in chief. Lincoln quickly realized it was risky to simply give his young friend a coveted government position or a high-ranking commission in the Regular Army, despite his faith in Ellsworth’s abilities. For Ellsworth’s part, he balked when he realized the negative attention his ambitions caused the new president and himself.

The story of the Lincoln-Ellsworth relationship is worth revisiting. It reminds us of the chaos of those early months of southern secession and impending conflict, and of the difficulties both men faced as they tried to navigate the new landscape of civil war. Lincoln’s relationship with Ellsworth revealed weaknesses in his judgment and limits to his authority. And Ellsworth’s impatience to prove himself as a soldier led to his death. The “power to command men” was never a given for anyone.

We do not know exactly when the two men met, but by early 1860, they had become acquainted enough that Lincoln sought to have Ellsworth clerk for him in his Springfield, Illinois, law office. At that time Ellsworth was preparing for a national tour with his Chicago Zouaves, yet he was mindful that he needed respectable employment to prove his worthiness to his fiancée Carrie Spafford’s family and lend financial support to his own parents. Since a very young age, Ellsworth had wanted to be a soldier. But without an officer’s commission in the Regular Army, it was not clear how he could fulfill his martial dreams and at the same time achieve middle-class respectability, something he desperately sought to make up for his humble beginnings in northern New York.

Lincoln believed he could help him and Ellsworth clearly understood the opportunity. Recognizing “that the influence of Mr. L would do me great service,” he told his fiancée in January 1860 that he admired Lincoln’s “early example” of earning “his subsistence while studying law, by splitting rails.”6 A few weeks later, Ellsworth related that a local judge told him that Lincoln “has taken in you a private interest that I [n]ever knew him to manifest in any one before.”7

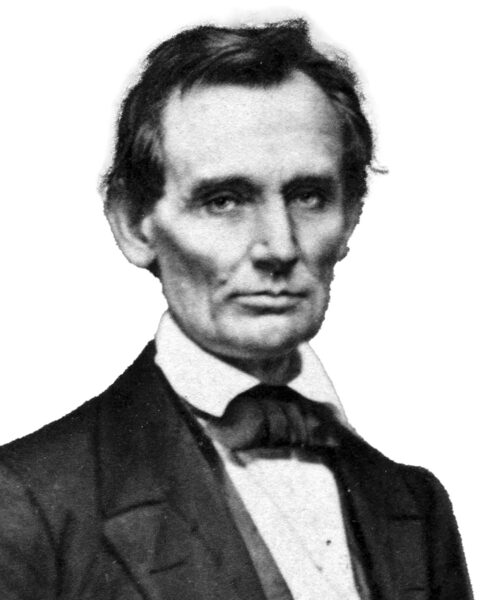

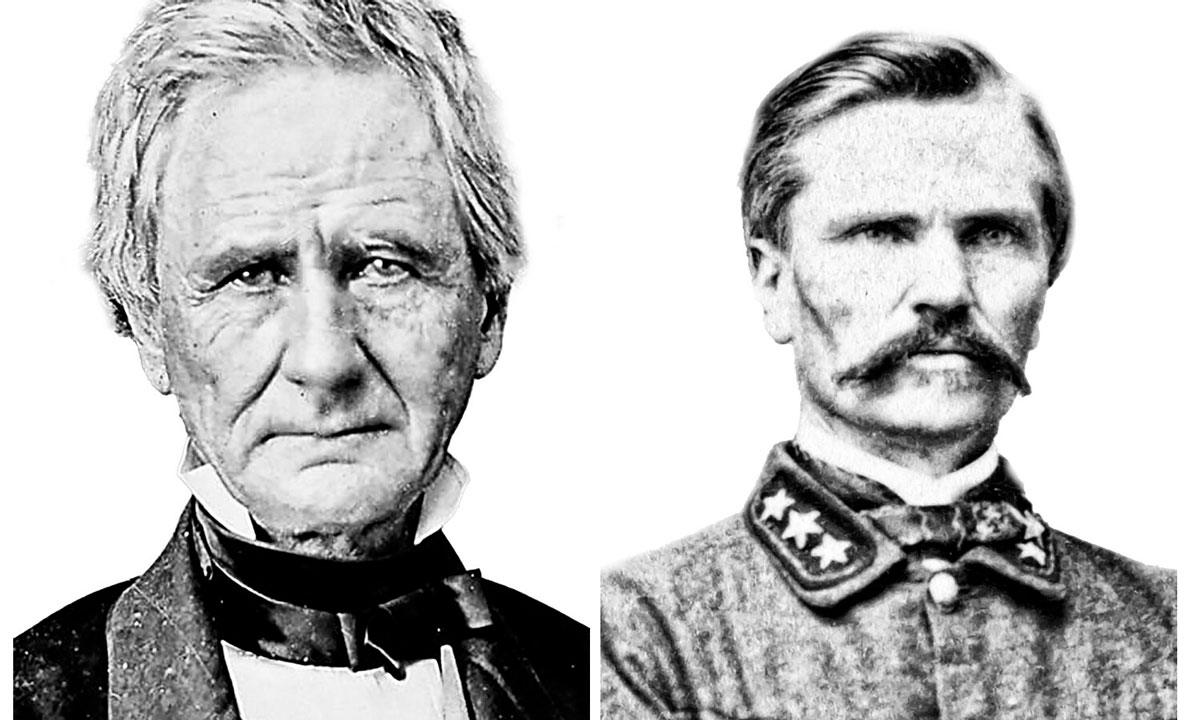

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionAbraham Lincoln in 1860

Ellsworth was 20 and living in Chicago, Illinois, studying military science in his spare time and helping to train local militia units. In 1859, he became colonel of the city’s National Guard Cadets. He had studied the Zouave soldiers, French colonial troops in Algeria, and soon transformed the unit into the United States Zouave Cadets, which became a finely trained militia he promoted as models of manly decorum and emulation. This was a time when the compulsory militia, the essence of America’s citizen soldiery dating from the colonial era, had fallen out of favor. The volunteer militia had arisen in its place, often being small local companies as much social clubs as military units. Ellsworth, enamored by the elite fighting reputation of the Zouaves in the Crimean War, sought to prove that Americans would “encourage military companies if they were worthy of respect.”8

Ellsworth created a set of “Golden Resolutions” for his recruits that forbade drinking, gambling, and entering “houses of ill fame,” and centered on the “power of discipline,” something he sought for himself as much as for the men he led.9 Ellsworth had survived impoverished conditions and near starvation and had little patience for anyone who resented his stringent rules or lacked the “moral courage” or “self control” to obey them. It was better, he believed, to reduce his company to a dozen worthy men than to have 100 who could not conform to these regulations.10

Some members bristled at the strict rules and grueling physical training, but most of Ellsworth’s cadets fell into line. At one point, he confided in his diary: “what a glorious thing it is to feel that you control the minds of men even though they be few in number there is pleasure in it”11 After a July 4, 1859, exhibition, he declared his company’s performance “a triumph.”12 The Chicago Press and Tribune described “thousands of lookers-on heartedly and repeatedly applauding their feats,” heralding them as the “crack corps of the city.”13

One year later, Ellsworth took his Chicago Zouaves on a three-month tour, visiting 20 cities and performing their acrobatic drills before throngs of electrified onlookers. It was the summer of 1860; sectionalism and threats of war were on the rise. Ellsworth and his Zouaves, with their colorful uniforms and choreographed movements, seemed both a distraction from and outlet for the intensifying national crisis. This was the citizen soldiery on display, but there was no violence, no suffering, no danger. It was all a grand spectacle. “Their drill and maneuvers are pronounced perfect,” declared the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel.14

There were critics, too, including those from the South. A Georgia editor, for example, sneered: “The same precision and celerity of movement, uniformity of action in grouping, changing, &c. may be seen at the theatres or operas during the performance of a troupe of dancing girls.” Dismissing “the whole thing” as “a mere series of theatrical effects,” he saw “nothing of the practical soldier about it,” doubting “if the Chicago boys will ever make a figure in history as mighty men of war.”15

Nevertheless, in their Springfield performance, Ellsworth and his Zouaves impressed Lincoln, who was in the enthralled crowd with his son Tad. Soon after, Ellsworth summarily disbanded the Chicago Zouaves and accepted Lincoln’s offer to clerk for him. He had promised his fiancée’s parents he would settle down to study law. But the presidential campaign was getting into high gear, and Ellsworth, with his newfound celebrity, agreed to serve as a surrogate and give campaign speeches for Lincoln. In October 1860, Ellsworth had written to Carrie Spafford that he “had no intention of engaging in this campaign as I thought it would require at least two months hard application & the study of political matters to fit myself for speaking.” Nevertheless, encouraged by his friends, and no doubt by Lincoln himself, he “set to work.” After about a week of preparation he made his debut on October 20 and was an instant success.

He explained in a letter to Carrie: “I believe it is arranged that I am to speak every day, until the election, in the county precincts.”16 A week before the election, he predicted to her: “The result of this winter will decide whether I am to be a Lawyer, Soldier, or a Politician, or a good-for-naught!”17 Ellsworth toured counties in central Illinois, giving rousing speeches almost every day in late October right up to the eve of the election. On Election Day, he accompanied Lincoln to vote and celebrated with him as the returns began to come in via telegraph.

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyIn the summer of 1860, Ellsworth took his Chicago Zouaves on a 20-city, three-month tour that wowed throngs of onlookers and received rave reviews in the Northern press. Above: an illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicts Ellsworth and his Zouaves during a performance.

The relationship between the two men only deepened. In February 1861, Ellsworth served as part of the president-elect’s security detail on the journey to Washington, helping to manage crowds and protect Lincoln from threats of assassination. At the White House, Ellsworth was a frequent guest, playing with Lincoln’s sons Tad and Willie and charming his wife, Mary. He was close enough to the boys that when they contracted measles, he got sick too. He had become, as one of Mary’s cousins described him, “a great pet in the family.”18

Ellsworth had not given up on his military dreams. He drafted an extensive proposal to reform the Illinois state militia, much of it based on his Zouave model including parts of his original “Golden Resolutions.” When it failed to make it through the state legislature, Ellsworth convinced Lincoln that there was a national need for such change, requesting an appointment as chief clerk in the War Department so he could implement a national Bureau of Militia. Lincoln assured him he would do all he could to help.

The president was true to his word. On March 5, 1861, the day after his inauguration, he penned a brief letter of support to Secretary of War Simon Cameron. Lincoln, though, was careful in his phrasing. “If the public service admits of a change without injury,” he wrote, “in the office of chief clerk of the War Department, I shall be pleased of [sic] my friend, E. Elmer Ellsworth, who presents this, shall be appointed.” He added that Cameron should inform him if he had “good reason to the contrary,” affirming that his request was “not intended to be arbitrary.”19 His first full day as president was an exceptionally busy one, but Lincoln took time for Ellsworth.

Seven states had seceded. The crisis at Fort Sumter had worsened and war was on the horizon. Lincoln faced a multitude of pressing decisions that would determine the fate of the nation. Amid all this, his selection of men to plum government positions, including military appointments, was unavoidably charged politically. Officers in the Regular Army, most of them graduates of the United States Military Academy, had endured years of slow promotions, low pay, and commands in far-off, isolated posts. The prospect of war meant unprecedented opportunities for them, as well as for others seeking favor with Lincoln. Ellsworth, for all his accolades as a drillmaster and militia officer, had no combat experience. Lincoln began to sense that it might not be so easy to give Ellsworth what he wanted, telling him: “that by & by, when things all get straightened out & I can see how the land lays,” he would put him “in the Army, somewhere.” Ellsworth, though, believed his militia reform could only happen outside the army.20

Simon Bolivar Buckner, a West Pointer and former Regular Army officer, tried to warn Ellsworth, reasoning that the chief clerkship in the War Department was not a position he would enjoy. Instead, Buckner advised him that he ask Lincoln for a commission as a second lieutenant, albeit a far lower rank than that to which Ellsworth aspired. Buckner predicted, as a native southerner himself who would soon resign to join the Confederacy, that there would be more and more vacancies available in the Regular Army. Buckner told Ellsworth that very soon he could reach his goal and “follow a soldier’s life,” not be someone pushing paper behind a desk.21

National Archives (Cameron); Library of Congress (Buckner)

National Archives (Cameron); Library of Congress (Buckner)Simon Cameron (left) and Simon Bolivar Buckner

Ellsworth seemed to accept some of Buckner’s advice. He gained a commission as a second lieutenant in the Regular Army’s First Dragoons, assuring his parents that he could then focus on the “Militia Business” and earn a comfortable salary of “about two thousand dollars a year for as many years as I propose or care to stay in the Army.”22 He had not given up on his plans to create a national bureau that would oversee each state’s militias, coordinate training, and centralize federal control when needed. Still, friends had warned him that “Old Military men are sensitive about young men rising suddenly in their way, & overturning old regulations & introducing innovations in the line of their profession.”23 Ellsworth was unfazed, boasting to his fiancée’s mother that he had the “positive promise of both Mr. Lincoln & Cameron to create the Bureau of Militia and make me chief of it.”24 But that plan fell apart when Ellsworth learned someone else had been appointed chief clerk.

Instead, Ellsworth worked up a convoluted scheme to have Lincoln appoint him to a vacancy in the Pay Department with a higher rank of major, which would, he determined, get him closer to heading up his federalized Militia Bureau. Obtaining support from two Regular Army officers, Major David Hunter and Captain John Pope, he visited Lincoln in person with his plan. Ellsworth’s account of the meeting recalled Lincoln admitting that he wanted “Col. Ellsworth to have a good place” but confessing: “I am pressed to death for time, and don’t pretend to know anything of military matters.” The president directed Secretary Cameron to “Fix the thing up so that I shant be treading on anybodies [sic] toes, or carrying anybody across lots, & then come to me & I’ll finish it.” According to Ellsworth, Mary Lincoln also pressured Cameron to “promise that I should have the majority.”25

Not long after this meeting, Ellsworth recounted a conversation he had with Brigadier General Edwin V. Sumner, at the time one of the highest-ranking officers in the Regular Army. Sumner was blunt about the sought-after promotion, explaining: “1st, that the position was so desirable that half of the Captains in the army were, & had been seeking it for years; 2nd, that it would arouse the ill will of these men against Mr. Lincoln, etc., etc.” It was a sobering assessment of his situation. Ellsworth then went directly to Secretary Cameron: “I told him that I would do nothing to cause ill feeling toward Mr. L. or himself & I would not therefore take the majority.” He would instead bide his time as second lieutenant, confident that Congress would move soon to “create the Bureau by law” and his promotion would follow.26

By now, Ellsworth was drawing some sharp public press. The Chicago Times scorned him as a “pompous captain” seeking a “fat office” in the War Department.27 The Chicago Morning Post further portrayed Ellsworth “any hour of the morning or evening promenading with some gay lady on each arm, the corridors at Willard’s.” “His style,” the newspaper stated, “is not the style of gentlemen in educated society.” The newspaper went on to disparage his dress as cheap and poorly fitting, his face as “not very intellectual,” and his “stare” as “impertinent.” “He will be regarded with amusement or mortification,” the Post derided, though Lincoln “seems to have adopted him and is determined to make a great man of him.”28

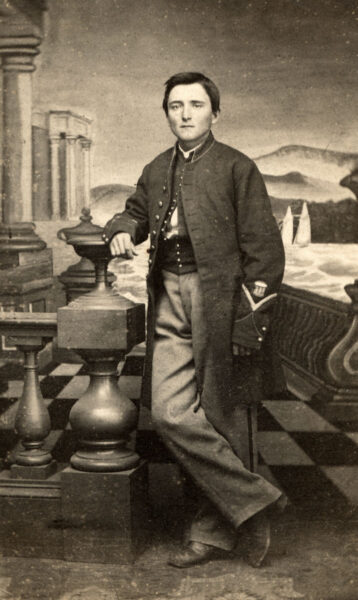

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionIn the months before the war, the ambitious Ellsworth (shown here in a photograph from 1861) began to receive negative attention in the press. The Chicago Morning Post, for instance, wrote of Ellsworth, “His style is not the style of gentlemen in educated society.”

The president was bent on helping Ellsworth, but he also was learning the limits of the office of chief executive. He forwarded a formal proposal to establish the Militia Bureau and designate Ellsworth “Adjutant and Inspector General of Militia” to Attorney General Edward Bates, requesting that he “give his opinion in writing whether the Executive has any lawful authority to make such an order as the forgoing.” On April 18 Bates replied that the president lacked the power to establish the bureau “without Congressional enactment” and “an explicit appropriation by Congress.”29

But everywhere the ground was shifting: Bates’ reply came just six days after Confederates had fired on Fort Sumter following repeated demands for its surrender, and three days after Sumter’s fall and Lincoln’s call for 75,000 state militiamen to defend the Union and “cause the laws to be duly executed.”30 Without Ellsworth’s proposed centralized Militia Bureau, Lincoln had to rely on individual states to provide the necessary troops. It was Congress, not the president, who could expand the army or formally declare war.

On the same day of his proclamation, Lincoln penned a short note to Ellsworth: “Ever since the beginning of our acquaintance, I have valued you highly as a person[al] friend and at the same time (without much capacity of judging) have had a very high estimate of your Military talent.” Although the president assured Ellsworth that he still sought “the best position in the military which can be given you,” it had to be consistent, he admitted, “with justice and proper courtesy toward the older officers of the Army—I can not incur the risk of doing them injustice, or a discourtesy.”31 Lincoln had to admit that there were limits to what he was willing to do—and jeopardize—to help the younger man.

Ellsworth quickly resigned his commission and left for New York City. He was, as friend and fellow former Lincoln law clerk John Hay later described, “without orders, without assistance, without authority, but with the consciousness that the President would sustain him.”32 He hurried to raise a new Zouave regiment consisting of the city’s volunteer firemen, boasting that he could have them ready for active service in a matter of days. He was determined to prove any naysayers wrong and command his own volunteer unit.

Within one week, Ellsworth had more than a thousand men signed up to join his First Fire Zouaves. But the basic bureaucracy of military institutionalism slowed things down; there were plenty of volunteers but not enough guns or other supplies. Their Zouave uniforms—purchased with donated funds—though colorful, were shoddy and thin. Nevertheless, Ellsworth pronounced with his characteristic impatience that his regiment had already “been playing soldier long enough” and the men were ready to begin “the actual duties of a soldier’s life.”33

On April 29, he marched his regiment triumphantly through the city’s streets to depart for Washington, D.C., cheered on by a boisterous crowd. There were rousing speeches and flag ceremonies heralding Ellsworth and his Fire Zouaves as brave men destined for martial greatness. Accepting one of the banners, Ellsworth admitted “that his acquaintance with the men had been brief, but he thoroughly understood their feelings, and he was sure that as long as one of them lived, that flag would never be disgraced.” He was, he confessed, “taking his command away without any drill, and he might almost say unformed; nevertheless, they were determined to do their duty, and he hoped to return with those colors as pure and unstained as they are now.”34

Near the end of their joyous parade, the regiment came to a sudden stop. There were too many men and the necessary enlistment papers had not been filed properly. Ellsworth made a special plea to Major General John Wool to make an exception and allow them to muster in once they got to Washington. Wool conceded, the crowd cheered, and the Fire Zouaves resumed their march. Ignoring protocol and rules, his advocacy for training and self-control evaporated, Ellsworth rushed on to what he believed was military glory.

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyShortly after the firing on Fort Sumter, Ellsworth raised a regiment of “Fire Zouaves”—volunteer firefighters who mustered into federal service as the 11th New York infantry—and led them to Washington, D.C. Shown here: Harper’s Weekly published this full-page illustration of scenes depicting Ellsworth’s Zouaves in camp in its June 8, 1861, issue.

Within days, Ellsworth had arrived in Washington and his men formally mustered into federal service for three years as the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry— the first volunteer unit, Ellsworth would insist, to do so. Lincoln and his son Tad witnessed the regiment’s swearing in on May 7. As their new colonel, Ellsworth gave a stirring speech contrasting the Zouaves to “dandy” units that had enlisted for only 30 days. He warned any man who wanted to go home and not serve to “get out of sight before we see him.”35

Negative press coverage, though, enveloped the Fire Zouaves now as much as it did their colonel. There were disquieting accounts of Ellsworth’s men stealing, brawling, harassing women, and setting fires just so they could put them out. As New York City firemen, they balked at discipline and conformity, proud of their reputation as rabble-rousers. Such behavior clashed dramatically with the stringent code of conduct Ellsworth had instituted with his Chicago Zouaves and his Golden Resolutions. The men of the 11th also earned the moniker “Lincoln’s pet lambs,” emphasizing the perceived favoritism the president extended to the entire regiment, not just to its commander.36

For his part, Ellsworth worked mightily to control his men, punishing what he called a handful of miscreants and paying for any property damage out of his own pocket. He assured Carrie: “The reports that the men are bad & that 150 have been sent back is false. We have sent back but 6 and the men do well.” He bragged that his regiment was “the first sworn in for the War & Ranks first now.” President Lincoln and Secretary Cameron, he insisted, were “giving everything I ask for & say my regiment is without exception the best [in] the service of the U.S.” He predicted a “fight within 10 days,” with his Fire Zouaves “promised a post of honor.”37

In the meantime, they had a chance to bolster their reputation by helping to put out a fire that raged near Washington’s famed Willard Hotel. Their quick action, with Ellsworth using a brass trumpet to direct his men, quickly doused the flames and prevented them from spreading. Accounts appeared in major newspapers, including Harper’s Weekly, which featured a front-page illustration of the Zouaves forming a human ladder to reach the heights of the buildings, with one man held upside down so he could spray water through an open window.38 Afterward, the commander of the Department of Washington, Brigadier General Joseph K. Mansfield—who days earlier had reprimanded the regiment for the destruction of local property by some of its members—addressed the Zouaves from the balcony of the hotel with “an enthusiastic speech,” predicting that if they performed as “well in actual warfare as they had in battling with that fire[,] they would render an excellent account of themselves.”39

Soon the 11th New York moved a few miles outside of Washington to “Camp Lincoln,” across the Potomac River from the city of Alexandria, Virginia. The scenes and sounds of that nearby town bemused and annoyed the Fire Zouaves, especially the sight of rebel flags flying from buildings. They took particular notice of one such flag, which was enormous and could be seen through field glasses. A few Zouaves plotted to steal across the river and “bear it down in triumph.” Ellsworth learned of the plan and “positively refused to countenance it.”40 His friend John Hay would later claim that the large banner was visible from the White House and bothered Lincoln too. Ellsworth, Hay attested, admitted to a “temptation to tear it down with his own hands.”41

Through all of this, Ellsworth was still confident that he had the president’s ear. Upon learning that plans were afoot to move troops into Alexandria, he went directly to the White House, telling Lincoln “that he would regard it as a personal favor to move in the advance.” Morale in his command was low and the negative press reports continued. Ellsworth was quoted as telling the president: “They must be got into the field, and they must be got in first.” Lincoln responded cautiously, stating that the situation was delicate and that he did not want to further inflame the people of Virginia, whom he believed were largely loyal.42 Ellsworth made a similar plea to General Mansfield, again affirming that he “would consider it as a personal affront if he would not allow us to have the right of the line, which is our due, as the first volunteer regiment sworn for the war.”43

Ellsworth got his wish and the 11th was selected as one of the first regiments to enter Alexandria in the early morning hours of May 24. Ellsworth was instructed to coordinate with other units involved in the advance, including the 1st Michigan Infantry commanded by Colonel Orlando Willcox. When Willcox learned that Ellsworth had gone ahead to enter the city without his knowledge, he was apoplectic, accusing the Zouaves of treating him and his men “cavalierly” and going on their “own way oblivious of orders, reckless and debonair, in true Zouave d’Afrique style.”44

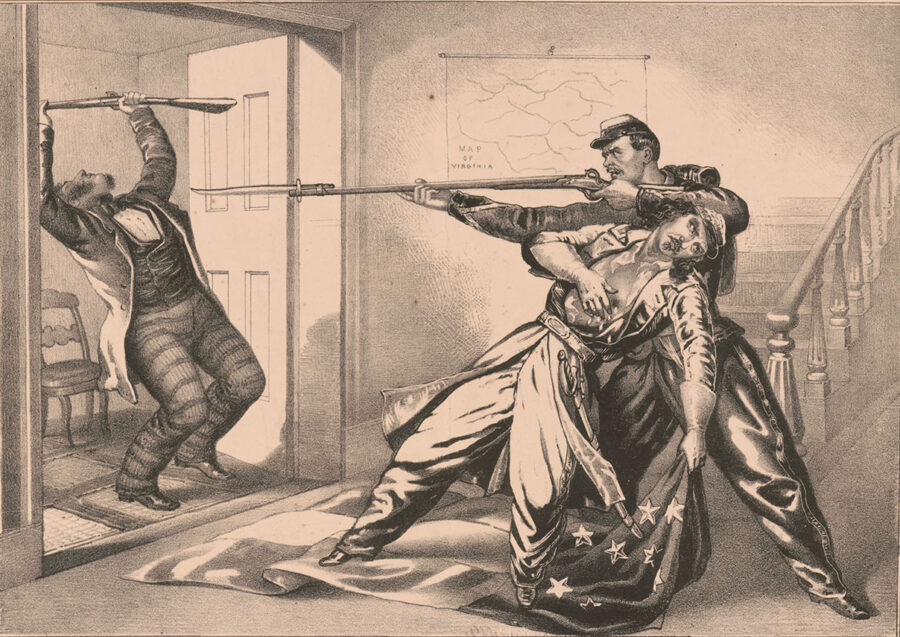

Ellsworth dashed into town with a small squad of men; once he spotted the huge rebel flag over the Marshall House, a local inn, he determined to remove it himself. As he descended the staircase after having cut down the flag from the building’s roof, the inn’s proprietor, James Jackson, met him with a fatal shotgun blast.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressElmer Ellsworth is shot dead— and instantly avenged—at the Marshall house in Alexandria, Virginia, in this illustration from 1862.

Frank Brownell, the Fire Zouave who had accompanied Ellsworth to the roof and then killed Jackson, later insisted that Ellsworth removed the flag to protect his own men who had felt taunted by it when encamped across the river. Ellsworth’s most recent biographer insinuates that his friendship with Lincoln was at least partly to blame and that Ellsworth intended to seize the flag that had “so taunted the president for weeks” to “personally present it” to him. Aware of the president’s loyalty, she writes, Ellsworth “owed Lincoln at least that much.”45

What is clear is that Ellsworth’s relationship with Lincoln helped get him to Alexandria. Lincoln had invited Ellsworth to join him in Washington, impressed by his charisma and magnetism. And Ellsworth had sought to use that connection to create his Militia Bureau with him as its chief. When that failed, he rushed to raise his Fire Zouaves, unwilling to admit that it would take time to transform firemen into soldiers. The pleasure he had taken years before in controlling “the minds of men” seemed to distort his own ability to manage himself. There was plenty of evidence that his regiment was far from ready for active service, yet he demanded that they be the first troops to enter Alexandria. Lincoln admitted that Ellsworth’s decision to rush into the Marshall House “was undoubtedly an act of rashness,” but that it displayed “the heroic spirit that animates our soldiers from high to low, in this righteous cause of ours.”46 These were the earliest days of civil war, and the rhetoric of heroism and righteousness did not yet ring hollow. That would start to change when the number of dead and wounded increased exponentially.

Lincoln had assured Ellsworth’s grieving parents that their son had an innate ability to command men. But we see in the story of their relationship obstacles in the younger man’s chosen path. He was frequently unable or unwilling to recognize the challenges associated with leading men, notably citizen-soldiers, into war. Ambition and impatience appear to have distorted his self-awareness. Lincoln, too, discovered limits to his powers of command and military judgment, strengths he would continue to hone and perfect over the four years before his own untimely death.

Lesley J. Gordon is the author of Dread Danger: Cowardice and Combat in the American Civil War (Cambridge University Press, 2024), which expands on Elmer E. Ellsworth and his Fire Zouaves’ fate. Since 2016, she has been the Charles G. Summersell Chair of Southern History at the University of Alabama. Presently, she is the Charles Boal Ewing Chair of Military History at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, for the academic year 2024–2025.

Notes

1. Abraham Lincoln to Ephraim and Phoebe Ellsworth, May 25, 1861, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln 8 Vols. (New Brunswick, NJ, 1953), Vol 4: 386. Some of the material in this article comes from my book, Dread Danger: Cowardice and Combat in the American Civil War (Cambridge, UK, 2024).

2. Abraham Lincoln quoted the New York Herald, May 25, 1861.

3. Baltimore Clipper quoted in The Daily Sun (Columbus, GA), July 30, 1860. For more on the Zouave phenomenon in the United States and beyond, see Carol E. Harrison and Thomas J. Brown, Zouave Theaters: Transnational Military Fashion and Performance (Baton Rouge, LA, 2024).

4. John Hay, “Ellsworth,” Atlantic Monthly, Volume 8, Issue 45 (July, 1861): 123.

5. Adam Goodheart, 1861: The Civil War Awakening (New York, 2011), 206; “special” from Meg Groeling, First Fallen: The Life of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the North’s First Civil War Hero (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2021), 197.

6. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Carrie Spafford, January 29, 1860, Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth Papers, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library ( ALPL).

7. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Carrie Spafford, March 11, 1860, Ellsworth Papers, ALPL.

8. Elmer E. Ellsworth Dairy, July 2, 1859, in Frank E. Brownell Papers, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN (MHS). For more on Ellsworth’s militia plans see Lesley J. Gordon, “‘Novices in Warfare’: Elmer E. Ellsworth and Militia Reform on the Eve of Civil War,” The Journal of the Civil War Era Vol. 11, No. 2 (June 2021): 194–223.

9. “Golden Resolutions” reprinted in Charles Ingraham, Elmer E. Ellsworth and the Zouaves of ’61 (Chicago, 1925), 27–28.

10. Ibid., 28.

11. Elmer E. Ellsworth Diary, June 4, 1859, Brownell Papers, MHS.

12. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Carrie Spafford [July 10, 1859], Ellsworth Papers, ALPL.

13. Chicago Press and Tribune, July 6, 1859.

14. Milwaukee Daily Sentinel (Milwaukee, WI), July 20, 1860.

15. Weekly Georgia Telegraph (Macon, GA) August 10, 1860.

16. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Carrie Spafford, October 21, 1860, Ellsworth Papers, ALPL.

17. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Carrie Spafford, October 28, 1860, Ellsworth Papers, ALPL.

18. Elizabeth J. Grimsley to John T. Stuart, May 24, 1861, in Harry E. Pratt, ed., Concerning Mr. Lincoln, In Which Abraham Lincoln Is Pictured As He Appeared to Letter Writers Of His Time (Springfield, IL, 1944), 81.

19. Abraham Lincoln to Simon Cameron, March 5, 1861, Basler, ed., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 4, 273.

20. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Abigail Spafford [March 22, 1861], Ellsworth Collection, ALPL.

21. Simon B. Buckner to Elmer E. Ellsworth, February 18, 1861, Ellsworth Collection, ALPL.

22. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Ephraim and Phoebe Ellsworth, March 12, 1861, Folder Ams 811/2.6, Ellsworth Papers, The Rosenbach Museum, Philadelphia, PA (RM).

23. M. Smith to Elmer E. Ellsworth, January 19, 1861, Box 2, Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth Papers, Brown University.

24. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Abigail Spafford [March 22, 1861], Ellsworth Collection, ALPL.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Chicago Times quoted in Randall, Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, 225–226.

28. The Chicago Morning Post, n.d., clipping in S.D. Beekman to Elmer Ellsworth, March 28, 1861, Elmer Ellsworth Papers, John Hay Library, Brown University.

29. Abraham Lincoln to Edward Bates, March 18, 1861, Basler, ed., The Collection Works of Lincoln, Vol. 4, 291–292. For Bates’ response, see editor’s annotation, 292. See also Simon Cameron to Abraham Lincoln, March 1, 1861, Folder AMs 811/2.8, Ellsworth Papers, RM.

30. Abraham Lincoln, “Proclamation Calling Militia and Convening Congress,” April 15, 1861, in Basler, ed., Collected Works of Lincoln, Vol. 4: 332.

31. Ibid., Vol 4: 333.

32. Hay, “Ellsworth,” 125.

33. New York Daily Tribune, April 29, 1861.

34. The New York Times, April 30, 1861.

35. Ellsworth quoted by John Hay in Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettinger, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Diary of John Hay (Carbondale, IL, 1999), 21.

36. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 23, 1861.

37. Elmer E. Ellsworth to Carrie Spafford, May 10, 1861, Ellsworth Collection, ALPL.

38. Harper’s Weekly, May 25, 1861.

39. Harrison H. Comings, Personal Reminiscences of Co. E. N.Y. Fire Zouaves; Better Known as Ellsworth’s Fire Zouaves (Malden, MA, 1886), 3.

40. “R.W.” to the Editors of the Sunday Mercury, May 18, 1861, in William B. Styple, ed., Writing and Fighting the Civil War: Soldier Correspondence to the New York Sunday Mercury (Gettysburg, 2000), 20.

41. John Hay, “A Young Hero,” The World, February 16, 1890.

42. Quotes from Frank E. Brownell, “Ellsworth’s Career,” (Philadelphia) Weekly Times, June 18, 1881.

43. “Ellsworth’s Last Speech,” in Frank Moore, ed., The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, with Documents, Narratives, Illustrative Incidents, Poetry, Etc., 12 Vols. (New York, 1861–1868), “Rumors and Incidents,” Vol. 2: 57.

44. Orlando Willcox, “Alexandria,” National Tribune (Washington, D.C.), December 25, 1884.

45. Groeling, First Fallen, 188.

46. Abraham Lincoln quoted in the New York Herald, May 25, 1861.