Library of Congress (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

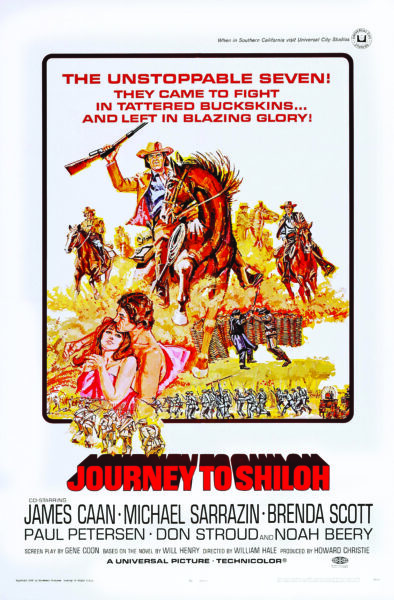

Library of Congress (Colorized by Pat Brennan)In this 1868 engraving by John Sartain, Ulysses S. Grant and his wife, Julia, pose with their children.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, high-ranking Union and Confederate officers were, on average, a decade older than the men in the ranks. And while those younger troops were more likely than not to be single (the number of Union soldiers married at the time of enlistment is estimated at around 30 percent), most men at the command level left wives behind when they departed for the war. Many of these women were long accustomed to the transient life of a military wife—their husbands having served at various postings in the antebellum U.S. Army after graduating from West Point—and had, or had to assume, primary responsibility for raising their children (if they had them) and overseeing their households. They also helped sustain their absent spouses, serving as their husbands’ confidantes and advocates, traveling whenever possible to be near them at the front, and even, on occasion, nursing their wounds. Here we highlight their images and their stories.

Julia Boggs Dent Grant Library of Congress (Colorization by Pat Brennan)

Library of Congress (Colorization by Pat Brennan)

Julia Boggs Dent Grant

(1826–1902)

Born: St. Louis, Missouri

Died: Washington, D.C.

Husband: Ulysses S. Grant (m. 1848)

Children: 4

![]() Julia Dent was raised on a plantation outside St. Louis—her father at one time owned nearly 30 enslaved people—and in 1844 was a student at a top local boarding school when her brother brought a West Point classmate home to meet his family. Ulysses S. Grant and Julia were engaged soon after, though the Mexican War delayed their marriage for four years. She endured separations from her military husband—he once wrote her, “you know dearest without you no place, or home, can be very pleasant to me”—until his resignation from the army in 1854. The family was in Galena, Illinois, where Ulysses worked in his family’s business, when he rejoined the army in 1861, beginning the war a colonel and ending it a lieutenant general. When she could, Julia traveled to the front to be near her husband (one historian estimates she logged over 10,000 miles), and they faithfully exchanged letters. They remained devoted to each other through his presidency and until his death in 1885 at 63 from cancer. “I thought my life had been lived, for we had been inseparable,” Julia later reflected. “I saw nothing that could brighten or make interesting the remaining years.” She died in 1902 at 76.

Julia Dent was raised on a plantation outside St. Louis—her father at one time owned nearly 30 enslaved people—and in 1844 was a student at a top local boarding school when her brother brought a West Point classmate home to meet his family. Ulysses S. Grant and Julia were engaged soon after, though the Mexican War delayed their marriage for four years. She endured separations from her military husband—he once wrote her, “you know dearest without you no place, or home, can be very pleasant to me”—until his resignation from the army in 1854. The family was in Galena, Illinois, where Ulysses worked in his family’s business, when he rejoined the army in 1861, beginning the war a colonel and ending it a lieutenant general. When she could, Julia traveled to the front to be near her husband (one historian estimates she logged over 10,000 miles), and they faithfully exchanged letters. They remained devoted to each other through his presidency and until his death in 1885 at 63 from cancer. “I thought my life had been lived, for we had been inseparable,” Julia later reflected. “I saw nothing that could brighten or make interesting the remaining years.” She died in 1902 at 76.

JULIA GRANT ON HER HUSBAND, ULYSSES:

“I always knew my husband would rise in the world…. I felt this even when we were newly married, and he was making a mere pittance in salary.”

Arabella Wharton Griffith Barlow Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Arabella Wharton Griffith Barlow

(1824–1864)

Born: Somerville, New Jersey

Died: Washington, D.C.

Husband: Francis C. Barlow (m. 1861)

Children: 0

![]() Arabella Griffith had moved to New York City in 1846 to be a governess and soon found herself connected to prominent literary, social, and political personalities. (Diarist George Templeton Strong called her “certainly the most brilliant, cultivated, easy graceful, effective talker of womankind, and has read, thought, and observed much and well.”) She met Francis Barlow, a Harvard graduate, and they fell in love. Griffith, 37, and Barlow, 26, married on April 20, 1861, the day before he left for the war as a lieutenant in a New York militia unit. In 1862, Arabella joined the United States Sanitary Commission, whose members helped care for wounded and sick soldiers. She nursed her husband (who rose to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers in 1862) after he received serious wounds at Antietam and again at Gettysburg. During the Overland Campaign, Arabella—whose colleagues had given her the nickname “the Raider” for her ability to secure supplies—was again near her husband at the front. She became ill in June 1864 and died of typhus the next month, at 40, in Washington, D.C. An army comrade reported Barlow “entirely incapacitated by … sudden grief.” In 1867, he married Ellen Shaw, sister of Robert Gould Shaw of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, and they had three children. He died in 1895 at 61.

Arabella Griffith had moved to New York City in 1846 to be a governess and soon found herself connected to prominent literary, social, and political personalities. (Diarist George Templeton Strong called her “certainly the most brilliant, cultivated, easy graceful, effective talker of womankind, and has read, thought, and observed much and well.”) She met Francis Barlow, a Harvard graduate, and they fell in love. Griffith, 37, and Barlow, 26, married on April 20, 1861, the day before he left for the war as a lieutenant in a New York militia unit. In 1862, Arabella joined the United States Sanitary Commission, whose members helped care for wounded and sick soldiers. She nursed her husband (who rose to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers in 1862) after he received serious wounds at Antietam and again at Gettysburg. During the Overland Campaign, Arabella—whose colleagues had given her the nickname “the Raider” for her ability to secure supplies—was again near her husband at the front. She became ill in June 1864 and died of typhus the next month, at 40, in Washington, D.C. An army comrade reported Barlow “entirely incapacitated by … sudden grief.” In 1867, he married Ellen Shaw, sister of Robert Gould Shaw of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, and they had three children. He died in 1895 at 61.

Mary Anna Custis Lee Cowan's Auctions, Inc. (Colorization by Pat Brennan)

Cowan's Auctions, Inc. (Colorization by Pat Brennan)

Mary Anna Custis Lee

(1807–1873)

Born: Boyce, Virginia

Died: Lexington, Virginia

Husband: Robert E. Lee (m. 1831)

Children: 7

![]() In early 1861, Mary Anna Custis Lee was torn over her state’s move toward secession. “[F]or my part, I would rather endure the ills we know, than rush madly into greater evils,” she confided in a letter to family. After Virginia voted to leave the Union, Mary’s husband, Robert E. Lee, resigned his U.S. Army commission and entered Confederate service. Mary, described as a lively and direct young woman, and Robert, then a young army officer, had wed in 1831 at Arlington House, her parents’ home, which Mary inherited in 1857. When war arrived, the couple had seven children, their three sons joining their father in Confederate service. Mary and her daughters—who in May 1861 had been forced to evacuate Arlington House—moved during the war between Richmond and area plantations. Confederate defeat hit Mary hard. “[W]e must submit to the will of Heaven but this is a bitter pill for the South to swallow,” she wrote on April 16, 1865. After the war, Lee served as president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, for five years. He died in 1870, at 63, and three years later, Mary, who had suffered from severe rheumatoid arthritis, died at 66.

In early 1861, Mary Anna Custis Lee was torn over her state’s move toward secession. “[F]or my part, I would rather endure the ills we know, than rush madly into greater evils,” she confided in a letter to family. After Virginia voted to leave the Union, Mary’s husband, Robert E. Lee, resigned his U.S. Army commission and entered Confederate service. Mary, described as a lively and direct young woman, and Robert, then a young army officer, had wed in 1831 at Arlington House, her parents’ home, which Mary inherited in 1857. When war arrived, the couple had seven children, their three sons joining their father in Confederate service. Mary and her daughters—who in May 1861 had been forced to evacuate Arlington House—moved during the war between Richmond and area plantations. Confederate defeat hit Mary hard. “[W]e must submit to the will of Heaven but this is a bitter pill for the South to swallow,” she wrote on April 16, 1865. After the war, Lee served as president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, for five years. He died in 1870, at 63, and three years later, Mary, who had suffered from severe rheumatoid arthritis, died at 66.

Eleanor Boyle Ewing Sherman Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Eleanor Boyle Ewing Sherman

(1824–1888)

Born: Lancaster, Ohio

Died: New York, New York

Husband: William Tecumseh Sherman (m. 1850)

Children: 8

![]() When Charles R. Sherman, a justice on Ohio’s supreme court, died unexpectedly in 1829, he left his widow and 11 children with no inheritance. Nine-year-old William was taken in by Sherman’s friend Thomas Ewing, a future U.S. senator, secretary of the treasury, and secretary of the interior. In 1850, Sherman, a West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran, married Ewing’s daughter (his foster sister) Eleanor (“Ellen”) Ewing. Ellen raised their children (two of whom died during the Civil War) and proved to be her frequently absent husband’s faithful defender. In 1861, after Sherman fell into a deep depression while stationed in Kentucky, some in the press labeled him “insane.” Ellen appealed to President Abraham Lincoln “for some intervention in my husband’s favor & in vindication of his slandered name.” “His mind is harassed by these cruel attacks,” she wrote. “Will you not defend him from the enemies who have combined against him, by removing him to the Army of the East?” Sherman rebounded and he became celebrated for his contribution to Union victory. Ellen died at 64 and before his death three years later, Sherman left instructions to be buried alongside his “faithful wife.”

When Charles R. Sherman, a justice on Ohio’s supreme court, died unexpectedly in 1829, he left his widow and 11 children with no inheritance. Nine-year-old William was taken in by Sherman’s friend Thomas Ewing, a future U.S. senator, secretary of the treasury, and secretary of the interior. In 1850, Sherman, a West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran, married Ewing’s daughter (his foster sister) Eleanor (“Ellen”) Ewing. Ellen raised their children (two of whom died during the Civil War) and proved to be her frequently absent husband’s faithful defender. In 1861, after Sherman fell into a deep depression while stationed in Kentucky, some in the press labeled him “insane.” Ellen appealed to President Abraham Lincoln “for some intervention in my husband’s favor & in vindication of his slandered name.” “His mind is harassed by these cruel attacks,” she wrote. “Will you not defend him from the enemies who have combined against him, by removing him to the Army of the East?” Sherman rebounded and he became celebrated for his contribution to Union victory. Ellen died at 64 and before his death three years later, Sherman left instructions to be buried alongside his “faithful wife.”

ELLEN SHERMAN TO HER HUSBAND, WILLIAM, OCTOBER 1861:

“Write me a cheerful letter that I may have it to refer to when the gloomy ones come.”

Mary Richmond Bishop Burnside The Providence Plantations (1886)

The Providence Plantations (1886)

Mary Richmond Bishop Burnside

(1828–1876)

Born: Providence, Rhode Island

Died: Providence

Husband: Ambrose Burnside (m. 1852)

Children: 0

![]() In 1852, young Mexican War veteran Ambrose Burnside was assigned to Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island. That year he married Mary Bishop of Providence, where the couple made their home. (Burnside’s first attempt at marriage some years earlier had ended when the bride left him at the altar.) After the Civil War—during which Burnside produced mixed results as a commander—he was elected governor and then to the U.S. Senate from his wife’s home state. Several years after Mary’s death at 47 in 1876 (Burnside died five years later at 57), a historian of Rhode Island wrote in remembrance of her, “[I]t was a daughter of Providence who by her sympathy and wifely devotion, cheered the heart of Rhode Island’s greatest military chieftain amid the dark hours of the conflict, thus linking … [her] to the earnest sisterhood that labored to sustain the brothers at the front.”

In 1852, young Mexican War veteran Ambrose Burnside was assigned to Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island. That year he married Mary Bishop of Providence, where the couple made their home. (Burnside’s first attempt at marriage some years earlier had ended when the bride left him at the altar.) After the Civil War—during which Burnside produced mixed results as a commander—he was elected governor and then to the U.S. Senate from his wife’s home state. Several years after Mary’s death at 47 in 1876 (Burnside died five years later at 57), a historian of Rhode Island wrote in remembrance of her, “[I]t was a daughter of Providence who by her sympathy and wifely devotion, cheered the heart of Rhode Island’s greatest military chieftain amid the dark hours of the conflict, thus linking … [her] to the earnest sisterhood that labored to sustain the brothers at the front.”

Flora Cooke Stuart Virginia Museum of History & Culture Colorized by CWM

Virginia Museum of History & Culture Colorized by CWM

Flora Cooke Stuart

(1836–1923)

Born: Jefferson Barracks, Missouri

Died: Norfolk, Virginia

Husband: James Ewell Brown Stuart (m. 1855)

Children: 4

![]() Flora Cooke Stuart’s family was one of many divided by the Civil War. Her father, Philip St. George Cooke, served as a Union general, while her brother, John Rogers Cooke, and husband, James Ewell Brown Stuart, served as generals in the Confederate army. Indeed, Stuart—who had proposed to Flora, 19, less than two months after meeting her at Fort Riley, Kansas Territory, in 1855—renamed their son from Philip St. George Cooke Stuart to James Ewell Brown Stuart Jr. because of his displeasure at his Virginian father-in-law’s decision to retain his U.S. Army commission. As her cavalryman-husband’s fame grew, distressing tales reached Flora. “Jeb” wrote in an October 1863 letter to her: “As to being laughed at about your husband’s fondness for society and the ladies, all I can say is that you are better off in that than you would be if I were fonder of some other things, that excite no remark in others. The society of ladies will never injure your husband, and ought to receive your encouragement.” Stuart was 31 when he was mortally wounded at Yellow Tavern in 1864. He died before Flora reached his side; she wore black mourning garb for the rest of her life and died at 87.

Flora Cooke Stuart’s family was one of many divided by the Civil War. Her father, Philip St. George Cooke, served as a Union general, while her brother, John Rogers Cooke, and husband, James Ewell Brown Stuart, served as generals in the Confederate army. Indeed, Stuart—who had proposed to Flora, 19, less than two months after meeting her at Fort Riley, Kansas Territory, in 1855—renamed their son from Philip St. George Cooke Stuart to James Ewell Brown Stuart Jr. because of his displeasure at his Virginian father-in-law’s decision to retain his U.S. Army commission. As her cavalryman-husband’s fame grew, distressing tales reached Flora. “Jeb” wrote in an October 1863 letter to her: “As to being laughed at about your husband’s fondness for society and the ladies, all I can say is that you are better off in that than you would be if I were fonder of some other things, that excite no remark in others. The society of ladies will never injure your husband, and ought to receive your encouragement.” Stuart was 31 when he was mortally wounded at Yellow Tavern in 1864. He died before Flora reached his side; she wore black mourning garb for the rest of her life and died at 87.

Mary Anna Morrison Jackson Virginia Military Institute (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

Virginia Military Institute (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

Mary Anna Morrison Jackson

(1831–1915)

Born: Lincoln County, North Carolina

Died: Charlotte, North Carolina

Husband: Thomas J. (“Stonewall”) Jackson (m. 1857)

Children: 2

![]() Mary Anna Morrison spent her early life among academics: Her father was the first president of Davidson College, in Davidson, North Carolina; her brother-in-law was on the faculty of Washington College, in Lexington, Virginia; and her sister introduced Anna to the man she would marry, Thomas J. Jackson, who was on the faculty of the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington. The couple, who were deeply religious (in a letter to Anna during their courtship, Jackson wrote, “And as my mind dwells on you, I love to give it a devotional turn, by thinking of you as a gift from our Heavenly Father”), married in 1857. (Jackson’s first wife had died in childbirth.) Anna moved to Charlotte when Jackson went off to war and visited him at his headquarters several times. After Jackson’s friendly-fire wounding at the Battle of Chancellorsville, she traveled to be at his bedside when he died, at 39, of pneumonia on May 10, 1863. She never remarried, raising their daughter (their first child died in infancy) and becoming known as “The First Lady of the South” among Confederate veterans who idolized her husband. Upon her death at 83, she was accorded military honors and buried next to him in Lexington.

Mary Anna Morrison spent her early life among academics: Her father was the first president of Davidson College, in Davidson, North Carolina; her brother-in-law was on the faculty of Washington College, in Lexington, Virginia; and her sister introduced Anna to the man she would marry, Thomas J. Jackson, who was on the faculty of the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington. The couple, who were deeply religious (in a letter to Anna during their courtship, Jackson wrote, “And as my mind dwells on you, I love to give it a devotional turn, by thinking of you as a gift from our Heavenly Father”), married in 1857. (Jackson’s first wife had died in childbirth.) Anna moved to Charlotte when Jackson went off to war and visited him at his headquarters several times. After Jackson’s friendly-fire wounding at the Battle of Chancellorsville, she traveled to be at his bedside when he died, at 39, of pneumonia on May 10, 1863. She never remarried, raising their daughter (their first child died in infancy) and becoming known as “The First Lady of the South” among Confederate veterans who idolized her husband. Upon her death at 83, she was accorded military honors and buried next to him in Lexington.

Martha Ready Morgan Case Auctions

Case Auctions

Martha Ready Morgan

(1840–1887)

Born: Readyville, Tennessee

Died: Lebanon, Tennessee

Husband: John Hunt Morgan (m. 1862)

Children (with Morgan): 2

![]() In February 1862, Charles Ready, a former U.S. representative from Tennessee, was visiting a Confederate army camp near Murfreesboro when he met the dashing Kentucky cavalry commander, John Hunt Morgan, and invited him to dinner. Ready sent word ahead with specific instructions for his daughter Martha: “[T]he famous Captain Morgan was coming. Tell Mattie that Captain Morgan is a widower and a little sad. I want her to sing for him.” On December 14, 1862, several days after Morgan, 37, was promoted to brigadier general, he and Mattie, 22, were married at the Ready home, a massive event attended by some leading Confederate generals, with regimental bands and several thousand Confederate troops at the celebration. Three weeks later, Mattie wrote to Morgan at the front, “Come to me my own Darling quickly. I was wretched but now I am almost happy and will be quite when my precious husband is again with me.” Morgan was 39 when he was killed in September 1864 while Mattie was pregnant with their second child (the first had died at birth). She remarried in 1873 and died at 47.

In February 1862, Charles Ready, a former U.S. representative from Tennessee, was visiting a Confederate army camp near Murfreesboro when he met the dashing Kentucky cavalry commander, John Hunt Morgan, and invited him to dinner. Ready sent word ahead with specific instructions for his daughter Martha: “[T]he famous Captain Morgan was coming. Tell Mattie that Captain Morgan is a widower and a little sad. I want her to sing for him.” On December 14, 1862, several days after Morgan, 37, was promoted to brigadier general, he and Mattie, 22, were married at the Ready home, a massive event attended by some leading Confederate generals, with regimental bands and several thousand Confederate troops at the celebration. Three weeks later, Mattie wrote to Morgan at the front, “Come to me my own Darling quickly. I was wretched but now I am almost happy and will be quite when my precious husband is again with me.” Morgan was 39 when he was killed in September 1864 while Mattie was pregnant with their second child (the first had died at birth). She remarried in 1873 and died at 47.

JOHN HUNT MORGAN TO HIS WIFE, MATTIE, DECEMBER 1862:

“How anxiously I am looking forward to the moment when I shall again clasp you to a heart that beats for you alone.”

Margaretta Sergeant Meade Anthony Waskie

Anthony Waskie

Margaretta Sergeant Meade

(1814–1886)

Born: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Died: Philadelphia

Husband: George Gordon Meade (m. 1840)

Children: 7

![]() “I cannot tell you how miserable and sad I am at parting from you and the dear children, and as the boat pushed off … the dock, I thought my heart would break.” So wrote Union general George Gordon Meade in August 1862 to his wife, Margaretta (known as Margaret), after leaving their Philadelphia home, where he had been recovering from wounds received at the Battle of Glendale. Margaret, who had helped nurse him, had by that time been married to George for over 20 years and had seven children. They had met in Washington, D.C., where Margaret lived with her family; her father, John Sergeant, who had been Henry Clay’s running mate in the presidential election of 1832, was a U.S. representative from Pennsylvania. Meade, who would gain fame in 1863 as the commander who defeated Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg, wrote Margaret regularly, often expressing pleasure at learning that fellow Union generals had stopped to pay their respects to her when passing through Philadelphia. He died at 56, having long suffered from complications caused by his war wounds, while Margaret lived another 13 years and died at 71.

“I cannot tell you how miserable and sad I am at parting from you and the dear children, and as the boat pushed off … the dock, I thought my heart would break.” So wrote Union general George Gordon Meade in August 1862 to his wife, Margaretta (known as Margaret), after leaving their Philadelphia home, where he had been recovering from wounds received at the Battle of Glendale. Margaret, who had helped nurse him, had by that time been married to George for over 20 years and had seven children. They had met in Washington, D.C., where Margaret lived with her family; her father, John Sergeant, who had been Henry Clay’s running mate in the presidential election of 1832, was a U.S. representative from Pennsylvania. Meade, who would gain fame in 1863 as the commander who defeated Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg, wrote Margaret regularly, often expressing pleasure at learning that fellow Union generals had stopped to pay their respects to her when passing through Philadelphia. He died at 56, having long suffered from complications caused by his war wounds, while Margaret lived another 13 years and died at 71.

Elizabeth Bacon Custer Heritage Auctions (Colorized by CWM)

Heritage Auctions (Colorized by CWM)

Elizabeth Bacon Custer

(1842–1933)

Born: Monroe, Michigan

Died: New York, New York

Husband: George Armstrong Custer (m. 1864)

Children: 0

![]() By the time Elizabeth “Libbie” Bacon turned 13, her mother and three siblings had died. Her father, a wealthy judge whom his late wife had urged “be both a mother and father” to Libbie, doted on her. She met George Armstrong Custer, a flamboyant and ambitious Union cavalry officer, at a Thanksgiving party in the fall of 1862. (“I supposed it was willed that we should meet,” a smitten Libbie wrote him.) Custer proposed marriage not long after, a union Libbie’s father opposed. After Custer, 23, was promoted the next year to brevet brigadier general for his battlefield exploits, Judge Bacon relented, and the pair married in February 1864. When Custer was called back to the front earlier than expected, Libbie, who begged not to be “left behind” in Washington, D.C., soon found herself “on the extreme wing of the Army of the Potomac, in an isolated Virginia farm-house, finishing my honeymoon alone.” After Custer’s death at Little Big Horn in 1876, Libbie became chief defender of his legacy, delivering lectures and writing three books in which she extoled his battlefield exploits and memory. She died days shy of her 91st birthday, having never remarried.

By the time Elizabeth “Libbie” Bacon turned 13, her mother and three siblings had died. Her father, a wealthy judge whom his late wife had urged “be both a mother and father” to Libbie, doted on her. She met George Armstrong Custer, a flamboyant and ambitious Union cavalry officer, at a Thanksgiving party in the fall of 1862. (“I supposed it was willed that we should meet,” a smitten Libbie wrote him.) Custer proposed marriage not long after, a union Libbie’s father opposed. After Custer, 23, was promoted the next year to brevet brigadier general for his battlefield exploits, Judge Bacon relented, and the pair married in February 1864. When Custer was called back to the front earlier than expected, Libbie, who begged not to be “left behind” in Washington, D.C., soon found herself “on the extreme wing of the Army of the Potomac, in an isolated Virginia farm-house, finishing my honeymoon alone.” After Custer’s death at Little Big Horn in 1876, Libbie became chief defender of his legacy, delivering lectures and writing three books in which she extoled his battlefield exploits and memory. She died days shy of her 91st birthday, having never remarried.

GEORGE ARMSTRONG CUSTER TO HIS WIFE, LIBBIE, ON THEIR FIFTH WEDDING ANNIVERSARY:

“You are all I ask for all I desire and all I long for. And I do long for you, every hour of my life.”

Lydia Mulligan Sims McLane Johnston American Civil War Museum Under the Management of Virginia Museum of History and Culture

American Civil War Museum Under the Management of Virginia Museum of History and Culture

Lydia Mulligan Sims McLane Johnston

(1822–1887)

Born: Wilmington, Delaware

Died: Washington, D.C.

Husband: Joseph E. Johnston (m. 1845)

Children: 0

![]() In 1843, army captain Joseph E. Johnston wrote his nephew, a cadet at West Point, about a rumor the young man had heard about his bachelor uncle’s dalliances: “No, no, … women are pleasant and attractive creatures, beyond denial, when one has nothing else to think of, or to excite him, but those who believe such a story know me little. There are—never were—women enough in the world to allure me from the chance of one hostile shot.” Two years later, Johnston, 38, ate his words and wed young Lydia Mulligan Sims McLane, daughter of onetime U.S. secretary of state and secretary of the treasury Louis McLane, in a Baltimore ceremony. As an army commander, Johnston’s Civil War career was mixed but he had a staunch and savvy supporter in Lydia. As southern diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut noted toward war’s end, “Mrs. Johnston knows how to be a partisan of Joe Johnston and still not make his enemies uncomfortable. She can be pleasant and agreeable, as she was to my face.” Lydia died at 65 and was buried in Baltimore; Johnston died three years later, at 84.

In 1843, army captain Joseph E. Johnston wrote his nephew, a cadet at West Point, about a rumor the young man had heard about his bachelor uncle’s dalliances: “No, no, … women are pleasant and attractive creatures, beyond denial, when one has nothing else to think of, or to excite him, but those who believe such a story know me little. There are—never were—women enough in the world to allure me from the chance of one hostile shot.” Two years later, Johnston, 38, ate his words and wed young Lydia Mulligan Sims McLane, daughter of onetime U.S. secretary of state and secretary of the treasury Louis McLane, in a Baltimore ceremony. As an army commander, Johnston’s Civil War career was mixed but he had a staunch and savvy supporter in Lydia. As southern diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut noted toward war’s end, “Mrs. Johnston knows how to be a partisan of Joe Johnston and still not make his enemies uncomfortable. She can be pleasant and agreeable, as she was to my face.” Lydia died at 65 and was buried in Baltimore; Johnston died three years later, at 84.

LaSalle Corbell Pickett Virginia Museum of History & Culture (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

Virginia Museum of History & Culture (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

LaSalle Corbell Pickett

(1843–1931)

Born: Chuckatuck, Virginia

Died: Rockville, Maryland

Husband: George Pickett (m. 1863)

Children: 2

![]() Sometime after the start of the Civil War, LaSalle (“Sallie”) Corbell, eldest of nine children born to a slaveholding family in Nansemond County, Virginia, fell in love with twice-married, 38-year-old Confederate general George E. Pickett. She was 20 when they married in 1863, a few months after the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg, where Pickett’s men participated in the ill-fated attack that bears his name to this day. After the war, the couple briefly relocated to Montreal while Pickett was under investigation for war crimes resulting from the execution in 1864 of 22 Union prisoners in Kinston, North Carolina. After Pickett’s death at 50 in 1875, Sallie, who promoted herself as the “Child-bride of the Confederacy,” became a leading proponent of the Lost Cause ideology, publishing books and delivering many speeches in which she romanticized the conflict and idolized her husband and his service. (She dedicated her book Pickett and His Men, published in 1900, “To my husband, the noble leader of that band of heroes whose deeds are sparkling jewels set in the history of the great Army of Northern Virginia….”) She died in 1931 at 87.

Sometime after the start of the Civil War, LaSalle (“Sallie”) Corbell, eldest of nine children born to a slaveholding family in Nansemond County, Virginia, fell in love with twice-married, 38-year-old Confederate general George E. Pickett. She was 20 when they married in 1863, a few months after the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg, where Pickett’s men participated in the ill-fated attack that bears his name to this day. After the war, the couple briefly relocated to Montreal while Pickett was under investigation for war crimes resulting from the execution in 1864 of 22 Union prisoners in Kinston, North Carolina. After Pickett’s death at 50 in 1875, Sallie, who promoted herself as the “Child-bride of the Confederacy,” became a leading proponent of the Lost Cause ideology, publishing books and delivering many speeches in which she romanticized the conflict and idolized her husband and his service. (She dedicated her book Pickett and His Men, published in 1900, “To my husband, the noble leader of that band of heroes whose deeds are sparkling jewels set in the history of the great Army of Northern Virginia….”) She died in 1931 at 87.

Maria Louisa Garland Longstreet The Longstreet Society (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

The Longstreet Society (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

Maria Louisa Garland Longstreet

(1827–1889)

Born: Fort Snelling, Minnesota Territory

Died: Gainesville, Georgia

Husband: James Longstreet (m. 1848)

Children: 10

![]() In 1844, young army officer James Longstreet met his regimental commander’s 17-year-old daughter, Maria Louisa Garland, who had come to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, to visit her father. Longstreet received permission to marry Louise, as she was called, but only when she was older. The couple wed in March 1848 in Virginia; five months later, with Louise pregnant, they went back to Missouri to attend the wedding of Ulysses S. Grant, with whom James had been close friends since their West Point days. In his Confederate service, Longstreet became one of Robert E. Lee’s most trusted generals. In early 1862, Louise wired him to hasten to Richmond; scarlet fever had hit the city, and their four children were sick. (Two children had died before the war.) Within weeks, three of the four were dead; months later, when Louise visited Longstreet at his headquarters, an officer noted “she has a very sad, subdued look & has lost all color from her face.” At war’s end, Louise was pregnant with their eighth child and was to have two more. The family eventually settled in Georgia, where in 1889, months after their house burned down, Louise died at 62. Longstreet, who remarried in 1897, died in 1904 at 82.

In 1844, young army officer James Longstreet met his regimental commander’s 17-year-old daughter, Maria Louisa Garland, who had come to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, to visit her father. Longstreet received permission to marry Louise, as she was called, but only when she was older. The couple wed in March 1848 in Virginia; five months later, with Louise pregnant, they went back to Missouri to attend the wedding of Ulysses S. Grant, with whom James had been close friends since their West Point days. In his Confederate service, Longstreet became one of Robert E. Lee’s most trusted generals. In early 1862, Louise wired him to hasten to Richmond; scarlet fever had hit the city, and their four children were sick. (Two children had died before the war.) Within weeks, three of the four were dead; months later, when Louise visited Longstreet at his headquarters, an officer noted “she has a very sad, subdued look & has lost all color from her face.” At war’s end, Louise was pregnant with their eighth child and was to have two more. The family eventually settled in Georgia, where in 1889, months after their house burned down, Louise died at 62. Longstreet, who remarried in 1897, died in 1904 at 82.

Elizabeth Hamilton Halleck National Portrait Gallery (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

National Portrait Gallery (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

Elizabeth Hamilton Halleck

(1831–1884)

Born: New York, New York

Died: Newport, Rhode Island

Husband: Henry W. Halleck (m. 1855)

Children: 1

![]() In 1855, when 24-year-old Elizabeth Hamilton— granddaughter of Founding Father Alexander Hamilton— married Henry W. Halleck, 40, the West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran was by then a wealthy civilian, having left the army to work as both a lawyer and land developer in California. When the Civil War began, Halleck reentered the military, and was appointed a major general in August 1861 before being promoted to general-in chief, a position he held from 1862 to 1864. Halleck—who earned the wartime reputation as excessively cautious and hard to work with or for—was replaced in 1864 (succeeded by Ulysses S. Grant) and spent the final year of the conflict as chief of staff of the Union armies. When he died in 1872 at 56, Elizabeth inherited over $400,000 (more than $11 million in 2023 dollars). In 1875 she married George Cullum, a former Union officer who for a time had been Halleck’s chief of staff. Her only child, Henry Jr., died in 1882. Before her death from cancer in 1884, at 53, Elizabeth helped finance the creation of the New York Cancer Hospital, known today as Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

In 1855, when 24-year-old Elizabeth Hamilton— granddaughter of Founding Father Alexander Hamilton— married Henry W. Halleck, 40, the West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran was by then a wealthy civilian, having left the army to work as both a lawyer and land developer in California. When the Civil War began, Halleck reentered the military, and was appointed a major general in August 1861 before being promoted to general-in chief, a position he held from 1862 to 1864. Halleck—who earned the wartime reputation as excessively cautious and hard to work with or for—was replaced in 1864 (succeeded by Ulysses S. Grant) and spent the final year of the conflict as chief of staff of the Union armies. When he died in 1872 at 56, Elizabeth inherited over $400,000 (more than $11 million in 2023 dollars). In 1875 she married George Cullum, a former Union officer who for a time had been Halleck’s chief of staff. Her only child, Henry Jr., died in 1882. Before her death from cancer in 1884, at 53, Elizabeth helped finance the creation of the New York Cancer Hospital, known today as Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Catherine Morgan McClung Hill University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center

University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections Research Center

Catherine Morgan McClung Hill

(1834–1920)

Born: Lexington, Kentucky

Died: Lexington

Husband: Ambrose Powell Hill Jr. (m. 1859)

Children (with Hill): 4

![]() After Catherine Morgan McClung’s husband, prosperous St. Louis merchant Calvin McClung, died in 1857, she traveled with her sister to Washington, D.C., to visit friends. At a party at Willard’s Hotel, Catherine (also known as “Kitty” and “Dolly”) met army officer Ambrose Powell Hill, who was instantly smitten. Powell, as his family called him, soon wrote his sister, “[T]here is now a little siren who has thrown her net around me…. She is a sensible little beauty, and if the spasm will stay in me long enough, and she will say ‘yes,’ why I don’t believe I could do better.” The couple married in July 1859 and her brother, future Confederate general John Hunt Morgan, was best man. During the war, Dolly and their three daughters would travel to be near Hill, who rose to corps command in the Army of Northern Virginia. After Hill, 39, was killed at Petersburg on April 2, 1865, Robert E. Lee dispatched an aide to inform Dolly, then pregnant with a fourth child, with the instruction, “Break the news to her as gently as possible.” She returned to Kentucky, remarried in 1870, had two more daughters, and lived to be 85.

After Catherine Morgan McClung’s husband, prosperous St. Louis merchant Calvin McClung, died in 1857, she traveled with her sister to Washington, D.C., to visit friends. At a party at Willard’s Hotel, Catherine (also known as “Kitty” and “Dolly”) met army officer Ambrose Powell Hill, who was instantly smitten. Powell, as his family called him, soon wrote his sister, “[T]here is now a little siren who has thrown her net around me…. She is a sensible little beauty, and if the spasm will stay in me long enough, and she will say ‘yes,’ why I don’t believe I could do better.” The couple married in July 1859 and her brother, future Confederate general John Hunt Morgan, was best man. During the war, Dolly and their three daughters would travel to be near Hill, who rose to corps command in the Army of Northern Virginia. After Hill, 39, was killed at Petersburg on April 2, 1865, Robert E. Lee dispatched an aide to inform Dolly, then pregnant with a fourth child, with the instruction, “Break the news to her as gently as possible.” She returned to Kentucky, remarried in 1870, had two more daughters, and lived to be 85.

Teresa DaPonte Bagioli Sickles Harper's Weekly (Colorized by CWM)

Harper's Weekly (Colorized by CWM)

Teresa DaPonte Bagioli Sickles

(1836–1867)

Born: New York, New York

Died: Brooklyn, New York

Husband: Daniel Sickles (m. 1852)

Children: 1

![]() Against her parents’ wishes, Teresa DaPonte Bagioli wed Daniel Edgar Sickles, a notorious womanizer twice her age, in a civil ceremony in New York City in 1852. Teresa, whose father was a famous Italian singing teacher, was 15 or 16 and described in the press as “very pretty and girlish, … well educated, and extremely attractive in manner.” She had known Sickles since he had lived for a time in the Bagioli home while studying at New York University; they became reacquainted in 1851 when he was a member of the state assembly. Sickles was elected to Congress in 1856, and the couple relocated to Washington, D.C., where both had extramarital affairs. After learning of Teresa’s dalliance with U.S. Attorney Philip Barton Key (son of the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner”), Sickles shot and mortally wounded Key. He was acquitted at trial on a defense of insanity and continued to serve in Congress. During the Civil War he was commissioned as a Union general and lost a leg at Gettysburg. In 1867, Teresa died at 31 of tuberculosis; Sickles remarried in 1871 and died in 1914 at 94.

Against her parents’ wishes, Teresa DaPonte Bagioli wed Daniel Edgar Sickles, a notorious womanizer twice her age, in a civil ceremony in New York City in 1852. Teresa, whose father was a famous Italian singing teacher, was 15 or 16 and described in the press as “very pretty and girlish, … well educated, and extremely attractive in manner.” She had known Sickles since he had lived for a time in the Bagioli home while studying at New York University; they became reacquainted in 1851 when he was a member of the state assembly. Sickles was elected to Congress in 1856, and the couple relocated to Washington, D.C., where both had extramarital affairs. After learning of Teresa’s dalliance with U.S. Attorney Philip Barton Key (son of the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner”), Sickles shot and mortally wounded Key. He was acquitted at trial on a defense of insanity and continued to serve in Congress. During the Civil War he was commissioned as a Union general and lost a leg at Gettysburg. In 1867, Teresa died at 31 of tuberculosis; Sickles remarried in 1871 and died in 1914 at 94.

Marguerite Caroline Deslonde Beauregard Heritage Auctions (Colorized by CWM)

Heritage Auctions (Colorized by CWM)

Marguerite Caroline Deslonde Beauregard

(1831–1864)

Born: St. John the Baptist Parish, Louisiana

Died: New Orleans, Louisiana

Husband: Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard (m. 1860)

Children: 0

![]() When Marguerite Caroline Deslonde, daughter of a prosperous Louisiana sugar planter, wed Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard in 1860 after a brief courtship, neither could imagine how brief their marriage would be. Beauregard, who had been a widower for 10 years, was soon off to serve as commandant of West Point, his alma mater; Caroline (as she was known) was of delicate health and remained in Louisiana. After a brief reunion when the Civil War broke out, Beauregard assumed command of Confederate forces around Charleston. The following year, with Union forces occupying New Orleans, Caroline’s health declined. In December 1862, friends of the Beauregard family were permitted to travel to Charleston to deliver the news to Beauregard and offer him safe passage to be with his wife; they also brought him a note from Caroline, who told her husband not to come, that his duty didn’t allow it—“The country comes before,” she reportedly wrote. Caroline died in March 1864 at 31. Some 6,000 people were said to have attended her funeral. The twice-widowed Beauregard died at 74 in 1893.

When Marguerite Caroline Deslonde, daughter of a prosperous Louisiana sugar planter, wed Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard in 1860 after a brief courtship, neither could imagine how brief their marriage would be. Beauregard, who had been a widower for 10 years, was soon off to serve as commandant of West Point, his alma mater; Caroline (as she was known) was of delicate health and remained in Louisiana. After a brief reunion when the Civil War broke out, Beauregard assumed command of Confederate forces around Charleston. The following year, with Union forces occupying New Orleans, Caroline’s health declined. In December 1862, friends of the Beauregard family were permitted to travel to Charleston to deliver the news to Beauregard and offer him safe passage to be with his wife; they also brought him a note from Caroline, who told her husband not to come, that his duty didn’t allow it—“The country comes before,” she reportedly wrote. Caroline died in March 1864 at 31. Some 6,000 people were said to have attended her funeral. The twice-widowed Beauregard died at 74 in 1893.

MaryEllen Marcy McClellan National Portrait Gallery (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

National Portrait Gallery (Colorized by Pat Brennan)

MaryEllen Marcy McClellan

(1835–1915)

Born: Green Bay, Wisconsin

Died: Nice, France

Husband: George B. McClellan (m. 1860)

Children: 5

![]() When West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran George B. McClellan proposed to Mary Ellen Marcy—daughter of Randolph B. Marcy, the army officer on whose Red River Expedition McClellan had served—in 1854 she turned him down. By the time she was 25, Miss Marcy had received nine offers of marriage; the one she accepted, in 1856, was from one of McClellan’s oldest friends (and future Confederate general) Ambrose Powell Hill. But her parents disapproved and when McClellan, now 32, proposed again in 1859, Ellen said yes; they married the following year. The couple remained devoted through 25 years of marriage. “My whole existence is wrapped up in you,” George once wrote Ellen, whom he called “my alter ego.” Through his meteoric rise and fall in the Union army, alternately confident and aggrieved, McClellan aired his feelings in his frequent letters to Ellen. McClellan died at 58 in 1885. Ellen died 30 years later, at 79, while visiting one of their children in France.

When West Point graduate and Mexican War veteran George B. McClellan proposed to Mary Ellen Marcy—daughter of Randolph B. Marcy, the army officer on whose Red River Expedition McClellan had served—in 1854 she turned him down. By the time she was 25, Miss Marcy had received nine offers of marriage; the one she accepted, in 1856, was from one of McClellan’s oldest friends (and future Confederate general) Ambrose Powell Hill. But her parents disapproved and when McClellan, now 32, proposed again in 1859, Ellen said yes; they married the following year. The couple remained devoted through 25 years of marriage. “My whole existence is wrapped up in you,” George once wrote Ellen, whom he called “my alter ego.” Through his meteoric rise and fall in the Union army, alternately confident and aggrieved, McClellan aired his feelings in his frequent letters to Ellen. McClellan died at 58 in 1885. Ellen died 30 years later, at 79, while visiting one of their children in France.

Selected sources

A Diary From Dixie (1906); “Boots and Saddles,” or Life in Dakota with General Custer (1885); Candice Shy Hooper, “The Two Julias,” New York Times Disunion blog, February 14, 2013; Robert M. Hughes, “Some Letters from the Papers of General Joseph E. Johnston,” The William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 11, no. 4 (1931); Shirley Farris Jones, “Morgan’s Wedding” (n.d.); William M. Lamers, The Edge of Glory (1961); Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson By His Widow, Mary Anna Jackson (1895); Marguerite Merington, ed., The Custer Story (1950); My Dearest Julia (2018); Pickett and His Men (1900); Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man (2007); James I. Robertson Jr., General A.P. Hill (1987); Stephen W. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (1988); The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade vol. 1 (1913); The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant (1975); The Providence Plantations for Two Hundred and Fifty Years (1886); Richard F. Welch, “A Civil War Love Story,” New York Times Disunion blog, July 27, 2014; Jeffry D. Wert, Cavalryman of the Lost Cause (2009) and General James Longstreet (1993).

Related topics: women