Edward Bates, Salmon P. Chase, and Gideon Welles could not have been more different—as politicians or people. But they shared one habit—for which historians are always grateful in their subjects—the practice of recording, day in and day out, the events of the American Civil War in their personal diaries. Diaries that, taken together, form an indispensable record of one of the most consequential presidencies in the nation’s history.

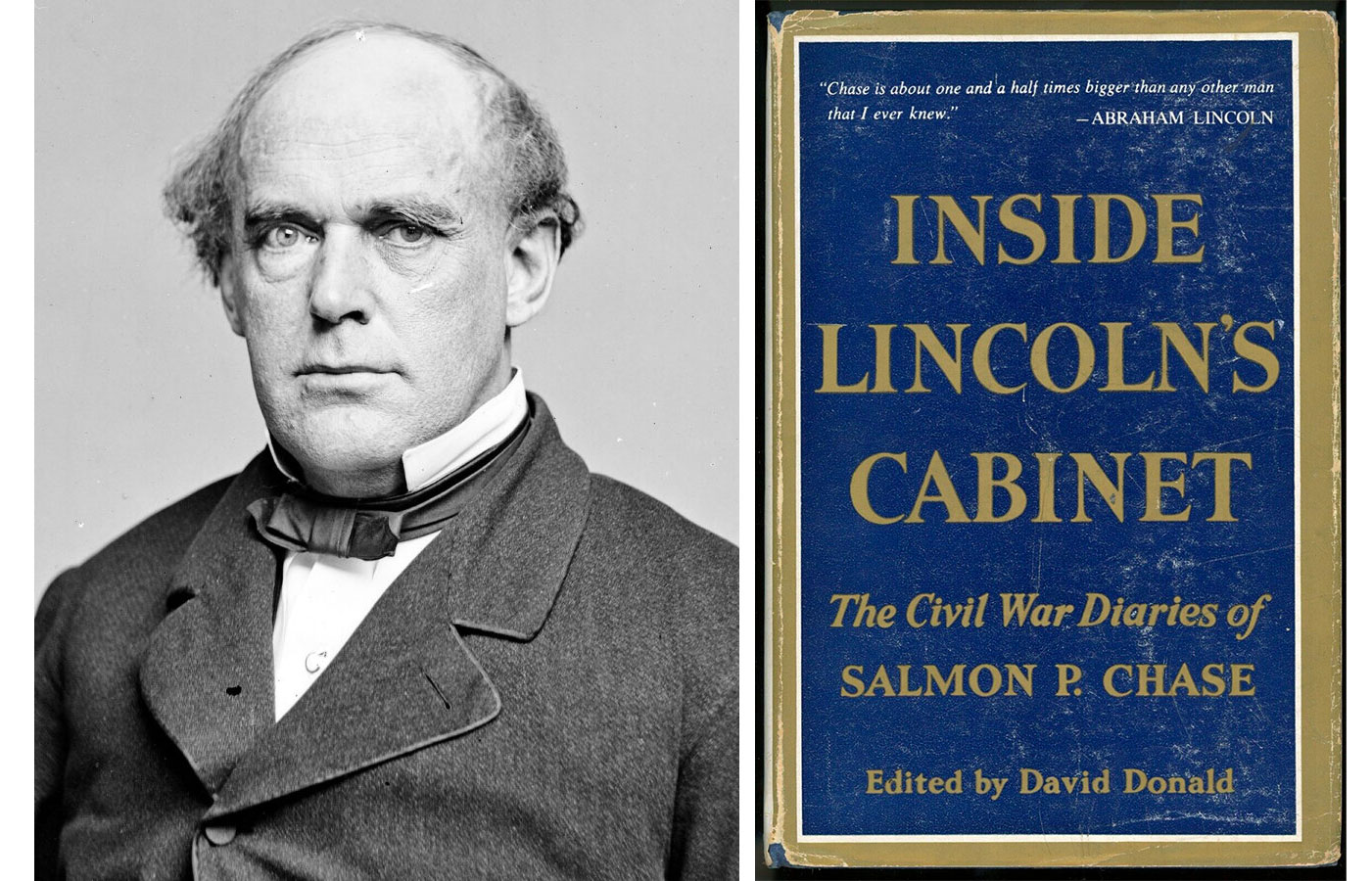

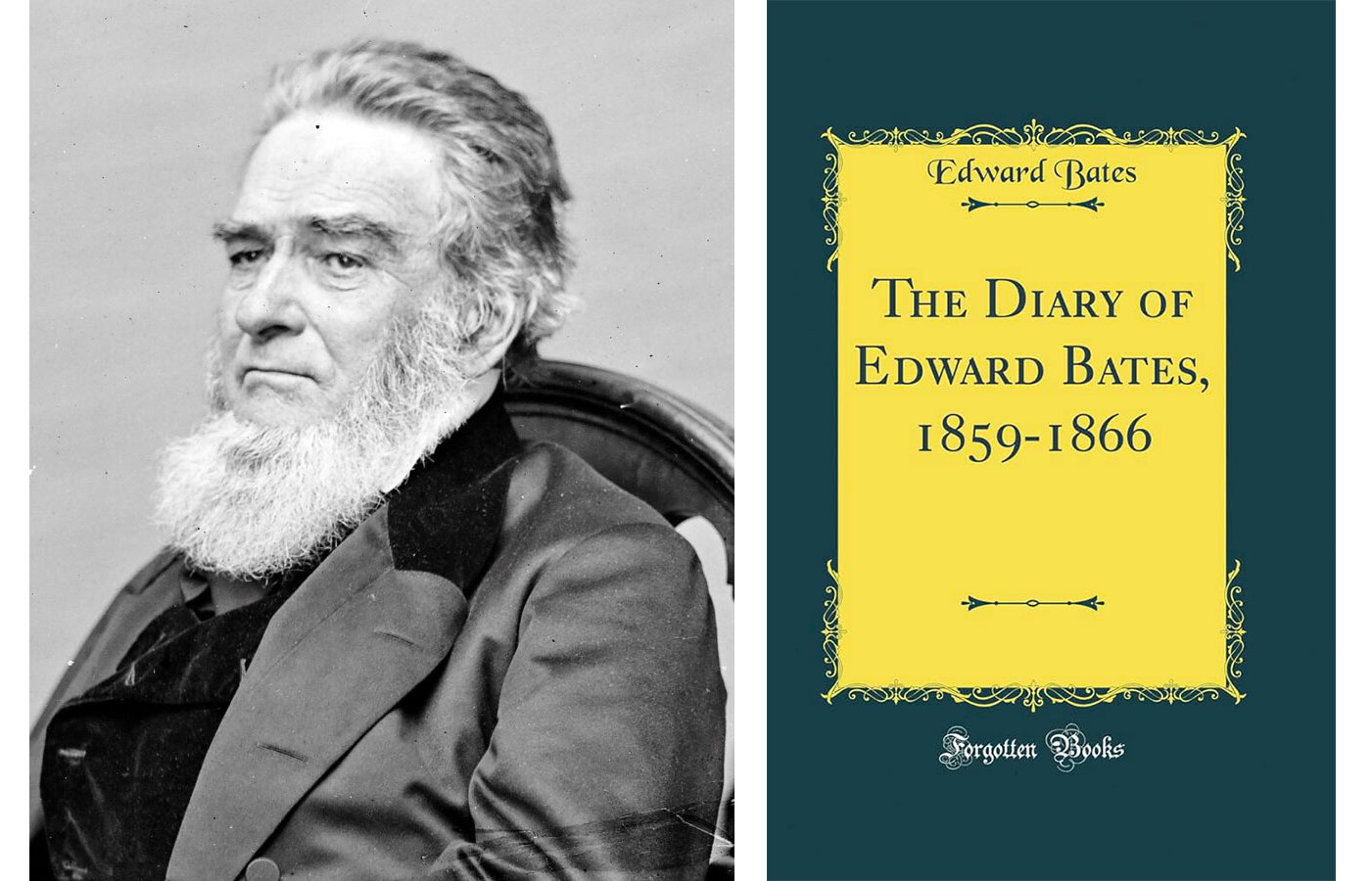

Bates and Chase served—as attorney general and secretary of the treasury, respectively—in President Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet from 1861 until 1864, when they resigned. Chase left because he had run out of patience with Lincoln’s moderate political positions, Bates because Lincoln rewarded Chase’s decision to step down by nominating him to be chief justice of the United States, a seat Bates coveted for himself.

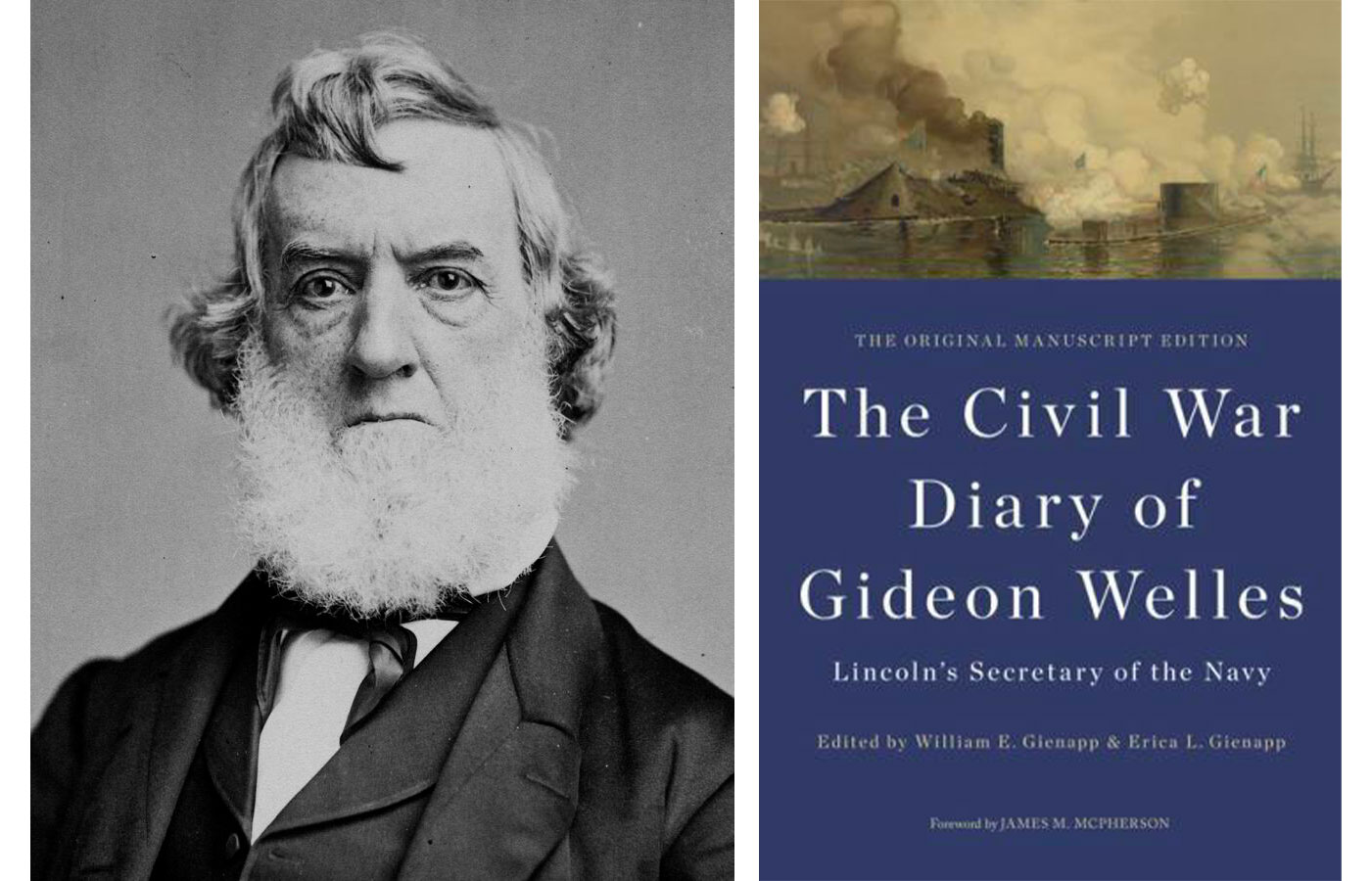

Welles was Lincoln’s secretary of the navy for the entirety of the war. He and Secretary of State William H. Seward shared the distinction of being the only two men to keep their cabinet seats for the entirety of Lincoln’s presidency.

National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryGideon Welles

Welles’ diary is the most comprehensive of the three. It is also the most frequently published, with the latest edition, a beautiful volume with lavish annotations by William E. and Erica L. Gienapp, titled The Civil War Diary of Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, published in 2014 by the University of Illinois Press. The diaries of Bates and Chase have not shared such good fortune, with only one standalone edition of each available to readers.

Chase’s wartime diary appeared in a single volume in 1954 from New York publisher Longmans, Green and Co. with the title Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet: The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase. Annotations were supplied by David Herbert Donald, the noted historian and Lincoln biographer. (The diary is also available as vol. 1 of The Salmon P. Chase Papers published by Kent State University Press in 1993.) Bates’ diary is the most obscure, appearing in its entirety in the 1933 Annual Report of the American Historical Association as The Diary of Edward Bates, 1859–1866. It was edited for the AHA by Howard K. Beale, an important but often forgotten historian of Reconstruction.

National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GallerySalmon P. Chase

Chase was easily the most radical of the diarists. He believed in emancipation and black civil rights, and often pressured Lincoln to act more aggressively to bring about the end of slavery in the United States. Bates tended to be the most conservative of the three men. Throughout his tenure, he took care to ensure that Lincoln’s wartime proclamations followed the letter of the law. Republican leaders had considered Bates a strong candidate for the presidency in 1860; he had even gained the backing of the influential newspaperman Horace Greeley before the erratic editor of the New-York Tribune threw his support behind Lincoln.

Welles, who had been a Democrat early in his political career and later a Free-Soiler, was a true centrist in the cabinet. But after the war, Welles stood by President Andrew Johnson’s side when Lincoln’s successor found himself assailed by the Radical Republicans, and he renewed his allegiance to the Democratic Party in 1868.

National Portrait Institute

National Portrait InstituteEdward Bates

The degree to which each of the three diarists followed the progress of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation reflected their political attitudes. Bates devoted no space to the cabinet’s discussion regarding the proclamation in the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam. Instead, on September 25, 1862, he offered a disquisition on colonization—a policy favored by conservative Republicans who hoped that free blacks would leave the United States for Africa or the Caribbean rather than live among the nation’s white population. Welles devoted a long diary entry to the September 22 meeting about the preliminary proclamation, in which he opined that the measure was “a step in the progress of this war which will extend into the distant future.” He admitted that he felt uncertain as to whether emancipation would, as some hoped, “insure a speedy peace.” Chase likewise described the meeting in detail, saying the document did not “mark out exactly the course that I should prefer,” but that he would nonetheless “stand by it with all my heart.”

The writers also took time to dissect and judge—unevenly so—the qualities of the war’s leading generals. Chase loathed conservative officers and reserved special vitriol for George McClellan, expressing “no confidence in his ability to handle a great army.” He heartily promoted the cases of John Pope and Irvin McDowell, rare Union officers who were avowed Republicans but middling battlefield commanders. Bates offered a more reasoned assessment of McClellan, though he still mocked “Little Mac” for his cautious nature. He thought McClellan had been promoted too quickly and with too much responsibility, leading to poor performance. “If left in command of a small army,” Bates confided, McClellan “wd. have done good service and made an honorable name.” Welles, who spent his days judging the capacity of naval officers, did not highly esteem many of the army’s leaders. Pope, who led the Union Army of Virginia in its decisive defeat at Second Bull Run, was “untruthful and wholly unreliable … a braggart and a blusterer” and Henry Halleck, who served as the army’s general-in-chief from 1862 to 1864, “heavy-handed,” wanting “sagacity, readiness, courage, and heart.” McClellan’s tenure in command, meanwhile, Welles judged as defined by “inertness, inactivity, and sluggishness.”

Despite his propensity for criticism, Welles proved an astute judge of one of the war’s most consequential partnerships—that of Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman. In August 1864, as the Army of the Potomac settled into its siege of Petersburg and the Army of the Tennessee stood on the precipice of conquering Atlanta, Georgia, Welles wrote that the two officers made a perfect pair. “There was something wanting in Grant,” Welles wrote, “that Sherman could always supply, and viso verso as regards Sherman.” “The two together,” he concluded “mad[e] a very perfect general officer.” And Grant and Sherman, in their memoirs, letters, and public declarations, proved the truth of Welles’ assessment—as when Sherman wrote to Grant of their complete trust in one another: “I knew wherever I was that you thought of me, and if I got in a tight place you would come—if alive.”

Politics and military affairs are two examples of the dozens of themes that emerge in the wartime writings of Chase, Welles, and Bates. What makes the diaries so valuable, to historians and any reader interested in better understanding the Civil War, is that they reveal the gargantuan effort to save the Union was not always unified. The men argued, differed in their views regarding the conduct of the war, and lampooned one another in the privacy of their journals. They closely followed rumors and political intrigues, professed expertise when acting out of ignorance, and frequently exhibited vanity. But each man also played a critical role in the success of the Union war effort—and their diaries provide a lasting testament of this triumph.

Cecily N. Zander is an assistant professor of history at Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas, and a senior fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. She is the author of The Army Under Fire: Antimilitarism in The Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2024).