Everett Collection, Inc. | Alamy Stock Photo

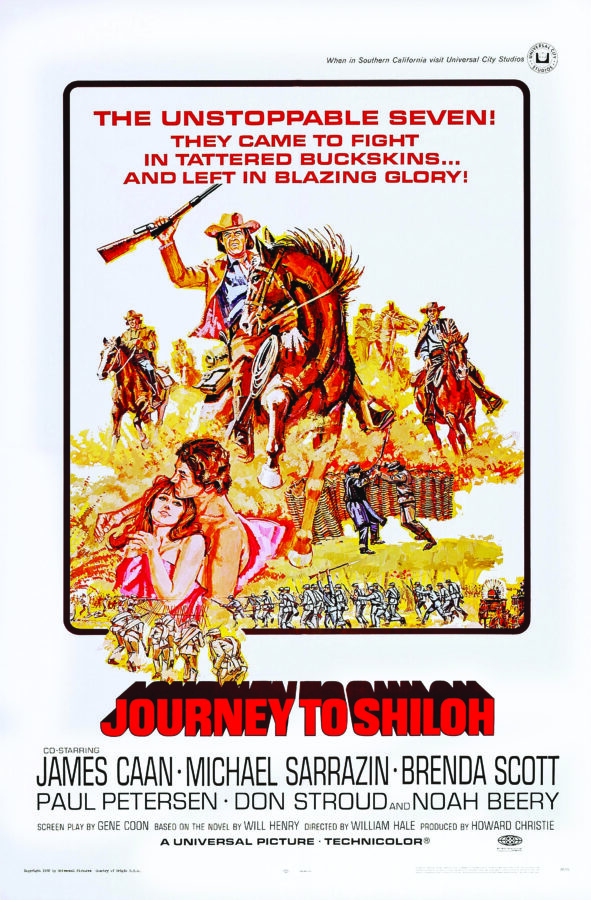

Everett Collection, Inc. | Alamy Stock PhotoWhile the 1968 film Journey to Shiloh was marketed (as in the movie poster shown here) as a thrilling tale of patriotic young men fighting in the Civil War, it delivered a decidedly anti-establishment message in tune with the antiwar movement of the time.

By the winter of 1967, Americans had been hearing for nearly three years that victory in South Vietnam was just around the corner. According to President Lyndon B. Johnson and his military advisers, Operation Rolling Thunder (a massive bombing campaign) and billions of dollars spent on cutting- edge weaponry had shattered North Vietnam’s will to fight. Indeed, it wasn’t a matter of “if” but “when” the Chinese-backed communists would surrender. Then on January 30, 1968, a coalition of North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces launched an enormous coordinated assault against several South Vietnamese cities. The Tet Offensive, as it came to be known, made a mockery of the president’s promises. Almost overnight, a stunned America lost faith in its military leadership. Even revered anchorman Walter Cronkite predicted—on his CBS nightly news program, no less—that the United States would not win the war in Vietnam. The antiwar movement’s popularity soared.

Enter seven patriotic young cowboys from Texas. Despite their fellow civilians not seeming to care about the war, these Texans were determined to serve their country in battle. Not long into their army careers, however, they became disillusioned; first with the doldrums of soldiering, next with their commander, and finally with the cause itself. In the end, only one of the seven made it home alive.

Such a synopsis could undoubtedly describe the experiences of countless young men who joined up and shipped out to fight communism in Southeast Asia—but it’s actually the plot of Journey to Shiloh (1968). Directed by William Hale and starring James Caan, this Universal Pictures release belonged to a wave of Western-themed Civil War movies produced in the late 1960s. And though it’s largely forgotten today, Journey to Shiloh represented a radical Hollywood experiment. Here was an attempt to deliver antiwar, anti-establishment politics through a combination of the quintessential coming-of-age American story, the Civil War, and what was still the most conservative, quintessentially American film genre, the Western.

Clad in buckskins, sporting shaggy hair, and packing six-guns, the seven Texans set out from Concho County in the spring of 1862. Their destination is Richmond, Virginia, and their plan is to enlist as cavalrymen in John Bell Hood’s famed Texas Brigade.

The leader of these so-called “Concho County Comanches” is Buck Burnett (Caan’s character, under the worst wig), an honest, upright young man who had been orphaned at age 2 by an Indian attack. His companions are Miller Nalls (“the loyal one”), Todo McLean (“the quiet one”), Eubie Bell (“the jester”), Little Bit Luckett (“Jed Luckett’s only son”), J.C. Sutton (“the fastest gun”), and Willie Bill Bearden, who received no appellation in the film’s earworm of an opening tune and was played by an unknown actor by the name of Harrison Ford.

From the outset, these “sons of the far frontier” are ardent and unquestioning supporters of the Confederacy because they assume it’s a universal cause among all “southern people.” They don’t understand much of the politics behind the war and they understand even less about for whom it’s being fought. In the course of their eastward odyssey, they learn war’s lessons the hard way.

On their way to a cotillion in Louisiana, the young men gawk naively at a slave. They confess to one man that they’ve never seen an African American before—“[T]here are no slaves where we come from.” That evening, the group is bounced by a wealthy planter who cares more about their low-class origins and haggard appearance than their noble quest to serve the Confederacy. “They are savages! They don’t belong here!” the plantation owner barks, as white-gloved slaves escort Buck and his crew outside. A few days later, the cowboys encounter a slave fleeing from hounds. They learn his name is Samuel and that he’s run away several times before. If the posse catches him, Samuel tells them, he’ll be killed. The Texans genuinely believe they are protecting him when they deliver him to the sheriff. Buck and Miller are astonished to see Samuel publicly hanged.

Near Corinth, Mississippi, the Concho County Comanches are tricked into joining the Army of Mississippi, under the command of General Braxton Bragg, who is depicted as an over-the-top martinet by veteran actor John Doucette. Little Bit is felled by disease before the army even reaches Tennessee and Shiloh. The others are killed one by one during the battle until only Buck and Miller remain. As night and then a storm falls over the battlefield, Buck seeks shelter. He stumbles into Miller and then a group of equally dissatisfied Federal soldiers. Rather than fighting, the men all pray together. Buck and Miller realize this wasn’t their fight after all. They don’t want to own slaves. They have no personal animosity toward northerners. They never should have left home. Finally, they attempt to desert, but are caught by Confederate provosts. Buck wakes up in a Confederate hospital, minus an arm—and learns that Miller has been shot by bounty hunters. In a penultimate scene that can only be described as head-scratching, he’s allowed to escape by the despotic Bragg. The movie ends with Buck riding to Shreveport, to pick up his fiancée before returning to Texas.

The parallels drawn between the fictional Concho County Comanches in 1862 and draft-eligible men in 1968 were visible to moviegoers. Journey to Shiloh depicts naive boys being lured far from their homes to fight a war that might as well have been foreign to them. It features out-of-touch commanders overseeing a classic “rich man’s war but a poor man’s fight.” And the plot exposes as farcical the idea of fighting for rights and liberties elsewhere when oppression is still rampant at home.

All of that said, Journey to Shiloh was not the first Civil War film to suggest dissension about the Vietnam War. Released in 1965, Shenandoah starred Jimmy Stewart (himself a highly-decorated WWII pilot) as an antiwar farmer in Virginia who watches the conflict destroy his family. Nor was Journey to Shiloh the first Western Civil War movie. Several such films came out in the mid-to-late ’60s; they often focused on treasure heists (Incident at Phantom Hill [1966]) or marauding guerrillas (Arizona Raiders [1965]). What made Journey to Shiloh unique is that it was the first Civil War picture to blatantly wield the Western, typically a bastion of American exceptionalism, against involvement in war.

Given the state of the genre in 1968, it’s not surprising that the studio tried a Western as the vehicle for this message. After decades of immense popularity, the Westerns produced by midcentury Hollywood had lost their grip on theatergoers. The days of patriotic, pro-military standards like Fort Apache (1948) and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) were well in the rearview. Likewise, the singing cowboys and upright heroes of traditional Westerns had been virtually dethroned by the antiheroes of Spaghetti Westerns (particularly Clint Eastwood’s “Man with No Name”) and the flawed protagonists of New Wave Westerns (like the Pike Bishop Gang from 1969’s The Wild Bunch). In other words, Journey to Shiloh had the perfect confluence of political and cultural trends going for it. Yet, the movie flopped—and is almost completely forgotten today.

Why?

One possibility is the film’s historical inaccuracies. The Concho County Comanches carry revolvers and rifles that did not exist in 1862; Civil War cavalryman were not in the habit of charging with sabers at entrenched infantry; Braxton Bragg did not command the Army of Mississippi at Shiloh (General Albert Sydney Johnston did, with General P.G.T. Beauregard as his chief subordinate); and, Texans did own slaves. Then again, other films enjoyed popularity in spite of far graver historical sins. Another possibility is that Americans, proud of their martial past, didn’t favor antiwar movies. And yet, the enduring popularity of films like All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), The Enemy Below (1957), and Dr. Strangelove (1964) stands up against that notion.

So what did doom the film to obscurity? Journey to Shiloh was conceptually clever. It bundled the antiwar sentiments of Shenandoah with cattlemen’s hats and six-shooters and pitched them to a presumably younger but still conservative audience. The bottom line may be that when the credits (mercifully) rolled, it signaled the end of an awful movie, which appears to have trumped all else. Negative reviews notwithstanding, Journey to Shiloh is still a lens into how the Civil War functioned as a tool for understanding—and in this case critiquing—the American Experience in the 20th century.

Matthew Christopher Hulbert is Elliott associate professor of history at Hampden-Sydney College. An expert on the Civil War in the West, guerrilla violence, and film history, he is the author or editor of five books. His most recent work is the biography Oracle of Lost Causes: John Newman Edwards and His Never-Ending Civil War (Bison, 2023), which was a 2024 Spur Award finalist.