Library of Congress

Library of CongressOne in 10 Union soldiers was underage when they enlisted. Their presence disrupted families, created chaos—and helped win the war.

In May 1861, the sounds of a fife and drum lured Thomas Hinds to a street in Philadelphia where he saw “both men and boys enlisting.”

The 16-year-old Irish immigrant entered the building, put down his name, and slept on the floor that night alongside his fellow enlistees. The next day, his parents found him and brought him home. A week later, Thomas joined a cavalry regiment that was immediately sent to a camp in New Jersey. His family again discovered his whereabouts and retrieved him, but within days he had returned to the camp. Lying about his age and forging his father’s signature, Thomas managed to get himself mustered into service. When Mr. Hinds came for his son this third time, he carried a writ of habeas corpus and was accompanied by a court official. Initially, Thomas’ captain promised to place the boy under military arrest to evade the writ, which required that he be brought before a judge to determine the legality of his enlistment. But once it became clear that such defiance could lead to his own colonel’s arrest, the captain backed down. Thomas was once again released to his father.

Boy soldier Library of Congress

Library of Congress

At home, Hinds tried to reason with his son. He even pledged to enlist himself—though at 50 he was well above military age—if only Thomas promised to stay home. But the boy was determined. In September 1861, after still more false starts, Thomas managed to join the 1st Maryland Cavalry. He served his full three-year term, during which he was taken prisoner, escaped to Union lines, and, in recognition of this improbable feat, earned a promotion to corporal. Thomas narrated his wartime experiences in a 1904 memoir.1 But his compiled service record, which otherwise substantiates his claims, only hints at Thomas’ underage status: Mustered into service as an 18 year old in 1861, he was discharged at age 19 in 1864, on paper having aged one year in three.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressDuring the Civil War, the term “boy soldier” did not evoke the negative connotation that “child soldier” does today.

Civil War service records are replete with such easily overlooked discrepancies. Misled by official documents, historians long claimed that youths under the age of 18 constituted between 1 and 2 percent of all Union army enlistees.2 In fact, their real number was much higher. Relying on regimental studies and the Early Indicators of Later Work Levels, Disease, and Death database—the largest resource for conducting quantitative studies on Union soldiers and veterans—we estimate that 10 to 11 percent of Union soldiers were under 18 at the time of their enlistment. Like Thomas Hinds, over 80 percent of these youths were 16 or 17, though many thousands of boys 15 and younger also served.3 And like Thomas, the vast majority did not enlist as drummer boys or musicians, but rather as regular soldiers.

Boy soldier Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Why and how did so many underage youths enlist in the Union army? How did the Lincoln administration, state and local judges, and politicians respond to aggrieved parents who looked to recover their sons from the military? Were underage enlistees treated differently from other soldiers, and how did their service shape their later lives? And how should knowing about the presence of so many young soldiers in the ranks affect our understanding of the Union war effort and the Civil War more broadly?

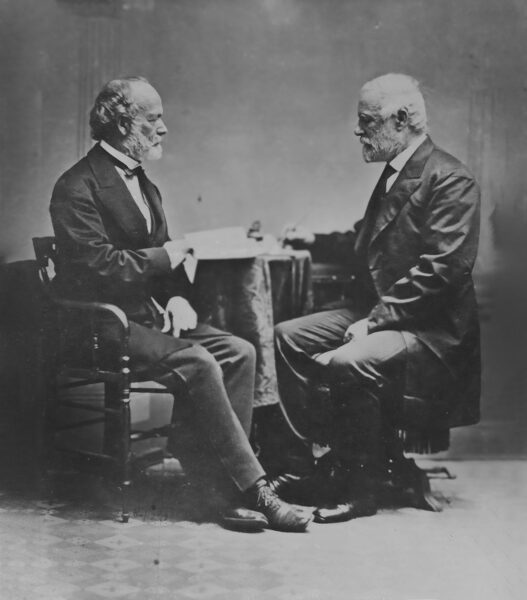

To begin to answer these questions, we must first clarify that the commonly used 19th-century term “boy soldier” did not evoke the negative connotations that “child soldier” calls to mind today. In our own times, child soldiers are portrayed as the ultimate victims: The arming of children is understood as a violation of human rights and international law that signals the breakdown of state institutions. In contrast, Civil War-era Americans were used to seeing boys in uniform and perceived nothing wrong with them performing certain kinds of military service. The U.S. Army accepted musicians from the age of 12, while the U.S. Navy relied heavily on boys as young as 13 to fill such roles as powder monkey and cabin boy, provided parents or guardians consented to the boy’s enlistment. Americans were also steeped in a militia tradition, dating to the Colonial era, that charged all able-bodied white males with responsibility for their community’s defense. Although the minimum age limit for militia service was set at 18 soon after the Revolution, many boys below that age turned out for militia duty or joined volunteer companies in the first half of the 19th century.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressJohnny Clem, like many of his boy solider comrades, tried and failed to enlist several times before being accepted as a drummer boy in a Michigan regiment. In the war, Clem served in several battles, was captured, and eventually rose to the rank of sergeant.

It was not difficult for a beardless boy to enter the Union army. At the war’s outset, military regulations stipulated that every recruit had to speak English and be between the ages of 18 and 35 (or above age 12 for musicians), at least 5 feet, 4.5 inches tall, and of sound mind and morals. Youths who had not yet turned 21—the legal age of majority—were only supposed to be accepted once a parent or guardian consented by signing their enlistment papers. Like all other troops, they were also supposed to pass a medical examination to affirm their capacity to serve. Yet although regulations sternly warned officials to be “very particular in ascertaining the true age of the recruit,” this was a difficult task in an era before the introduction of birth certificates and other forms of age certification.4 Moreover, ignoring or actively thwarting army rules was commonplace in the rush to fill the ranks. The huge volume of underage enlistees who signed up without their parents’ approval demonstrates the frequency with which mustering officers and army physicians looked the other way when it came to enrolling the young, as Thomas Hinds discovered when he managed to inveigle his way into not one, not two, but multiple regiments.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAn unidentified boy soldier from a Pennsylvania regiment.

Much like Hinds’ father, masses of parents tried to keep their children out of the military, but there was no outcry over the general idea of boys marching off to war. This is partly because mid-19th-century Americans had much lower expectations as to their ability to protect their children from life’s myriad hardships, including illness and early death. In cities, people were used to seeing children exposed to dirty and potentially dangerous situations, whether as sooty chimney sweeps or newspaper boys calling out on street corners. Most families also relied heavily on their minor children’s economic contributions, although the circumstances of their labor varied widely, from helping on family farms to toiling in factories or mines. Given the low wages and harsh conditions that many adolescent workers faced, a young son’s military enlistment must have seemed like a decent prospect to many families, particularly if he secured a bounty and sent home part of his pay.

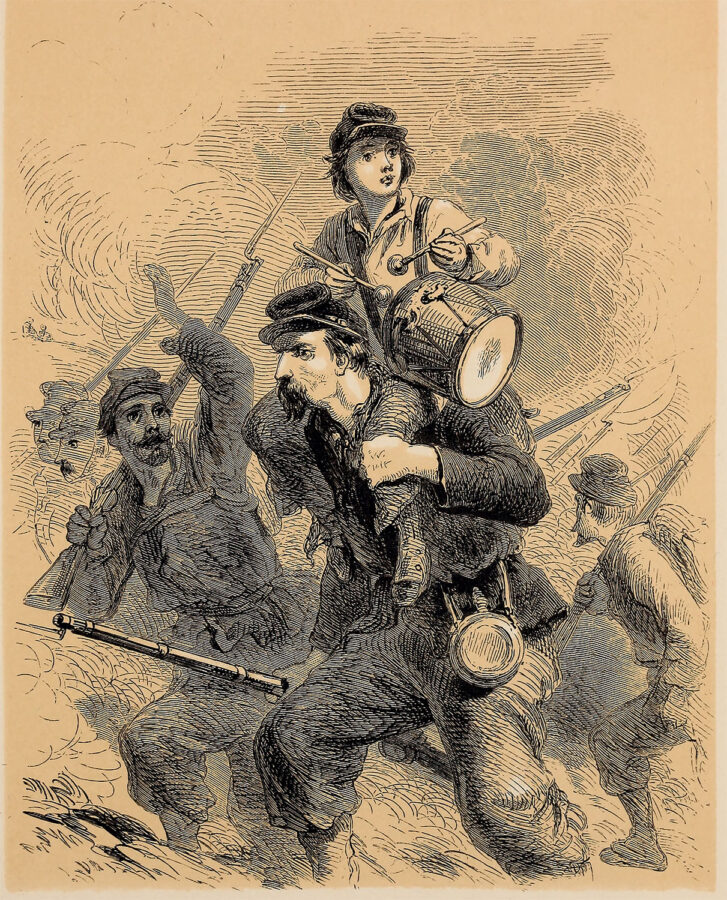

Lax enforcement of regulations and harsh economic realities are only a part of the explanation for how underage enlistment could occur on such a large scale. Unionists not only accepted but actively celebrated youths’ enlisting by extolling white drummer boys as the embodiment of republican virtue, drawing on a tradition established during the French Revolution. Artists and writers blanketed the nation with thousands of poems, songs, stories, and paintings that idealized young white boys as heroic American patriots who inspired older men while retaining their innocence amid the slaughter. Their imagery was regionally distinctive: Confederate supporters often lauded youthful enthusiasm for war, but they did not depict boy soldiers as national icons. It was also highly romanticized, misrepresenting the realities of camp life and combat, even as it undoubtedly inspired many boys to envision themselves in the ranks. So, too, did the popular juvenile literature that circulated at this time, which featured underage soldiers and sailors, including Oliver Optic’s 1863 books, The Soldier Boy and The Sailor Boy, which told of 16-year-old twins who enlisted, one in the army, the other in the navy.

"A Selection of War Lyrics" (1864)

"A Selection of War Lyrics" (1864)F.O.C. Darley’s illustration of a drummer boy carried on the shoulders of a Union soldier. While there were ever-present concerns about volunteers too young enlisting in the Union army, many Northerners were unfazed by the presence of boy soldiers, even celebrating them. Drawing on a tradition established during the French Revolution, drummer boys were singled out for praise as the embodiment of Republican virtue.

To say that Civil War-era Americans celebrated drummer boys or were unfazed by the presence of underage soldiers at war is not to say they were not concerned with questions around boys’ enlisting. During the conflict, military physicians expressed deep reservations about boys and youths serving in the ranks. In November 1862, Surgeon General William Hammond argued that raising the enlistment age to 20 was “imperatively demanded.”5 Like his fellow physicians, his concerns did not focus on the war’s potentially traumatizing effects on young minds; rather, he warned that young soldiers’ undeveloped bodies would break down under harsh wartime conditions, filling hospitals and depleting scarce military resources. Parents of underage soldiers repeatedly voiced the same fear. In the tens of thousands, anxious relatives wrote to military officials, typically addressing their letters to President Abraham Lincoln or Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Much like physicians, they focused on the potential that frail youths would succumb to sickness or disease—a rational fear when two-thirds of all war deaths derived from such causes. They also fretted that youths might return home morally corrupted, inured to vices like gambling, drinking, and swearing.

Library of Congress

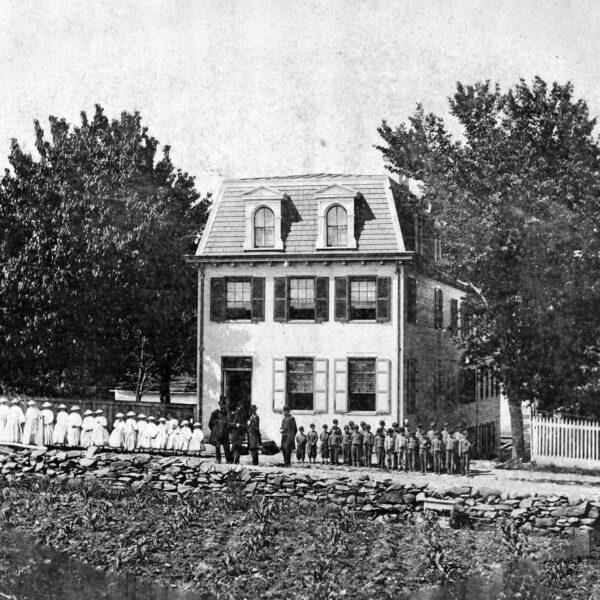

Library of CongressAn older Union sergeant stands beside five young soldiers in an undated wartime photo. Many underage soldiers secured their parents’ permission to enlist only when it was clear they would be serving alongside a family member or other trusted adult—or had received assurances from their sons’ commanding officers. Even so, some boy soldiers experienced teasing and even abuse at the hands of hardened comrades.

Parents who allowed their sons to enlist often did so only because they would be serving alongside an older relative or other trusted adult. Charles Willison, 16, overcame his parents’ resistance by joining a company commanded by the superintendent of his Sabbath school, “a careful, moral, kindly disposed man.” As Willison explained in his memoir, “[I]f boys were determined to go to war parents were willing if it should be under such a man.”6 Other parents of young soldiers sought reassurance from their sons’ commanding officers. When Jacob Cole, 14, enlisted, his mother sent his captain a letter “committing me to his care,” Cole recalled in his memoir, which prompted the officer to pay a visit to the family home. “[H]e promised my parents that he would act as a father to me,” Cole wrote, detailing how the captain had “carried my knapsack for miles at a time, and in many other ways he tried to assist me.”7

As Cole’s experience suggests, officers and ordinary soldiers alike understood that young enlistees typically lacked the capacities and stamina of full-grown men and could thus not be expected to exert the same self-control. Within the ranks, boy soldiers tended to be treated like informal apprentices, requiring both care and discipline as they endured the challenges of adult soldiering. In countless small ways, officers and enlisted men made allowances. A boy might be hoisted onto a wagon on a long march, released from certain onerous duties in camp, or, during intense fighting, detailed to a position behind the lines. Such was the case for William Ellis, 17, who wrote to his mother that he had been relieved of guard duty for the time being, tasked only with cooking for his captain and a lieutenant. “Davis got me this place sow it would not be sow hard for me,” he explained, “sow I have pretty easy times.”8 Of course, no protection could be failproof in war. When W.B. Smith, 15, enlisted, he found himself quickly adopted by “nine big bronzed brothers in arms” who “shielded” him as if he were “their own younger brother,” but he still suffered so grievously in Confederate prisons that his health was permanently destroyed.9

Other underage enlistees encountered quite different treatment, ranging from mild teasing to outright abuse. At 16, Frank Wilkeson enlisted out of patriotic enthusiasm, only to find himself immediately placed in a guarded barracks with hardened conscripts and bounty jumpers. As a volunteer from a well-connected family, he was granted a pass to come and go at will; when he refused to yield it up, the men attacked him.10 Even more perilous situations confronted large numbers of black and white youths who were scooped up by corrupt recruiters, impressed into service, and had their bounties stolen. Without the strength or experience of their older comrades, boy soldiers became easy prey for adults eager to divest them of their due—or worse.

In general, though, young soldiers tended to be shown special leniency—a trend most clearly evident in courts-martial records. Judging simply from the Articles of War—which laid out the rules of military conduct and punishments for violation of those rules—age never factored into military decision-making. But in practice, boys and youths were often treated differently than adult men, albeit in ways that rarely called into question the legitimacy of their service. Their presence compelled the army to adopt a common language and set of practices that in effect acknowledged the vulnerabilities of boy soldiers. This is evident in the mitigated sentences that many of them received “on account of youth” or “on account of extreme youth” when found guilty of violating military law. For soldiers convicted of sleeping on post, for example, court-martial sentences could be harsh, entailing lengthy prison terms and loss of pay for many months. Penalties meted out to boy soldiers were usually less severe: perhaps a month’s confinement on bread and water; having to stand on a barrel for several hours a day while wearing a placard reading “sleepy head”; a few months on limited pay; or a few weeks of hard labor.

Officers who failed to take age into account could find their own behavior scrutinized. Court-martial panels occasionally acquitted young defendants entirely of charges like sleeping on post or falling out of the ranks, instead blaming officers for overtaxing them. This was the case for Henry Brown of the 3rd Alabama Infantry, U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), who fell asleep on guard duty. Although witnesses testified that Brown was 18 years old and had been fully briefed on his responsibilities, his court-martial panel concluded that he was “evidently too young and ignorant for a soldier” and handed down a trifling sentence (to have his hands tied behind him and paraded in front of his company quarters for four hours over four days). The brigadier general who reviewed the case agreed; declaring the private a “mere boy” who had erred out of “ignorance,” he disciplined Brown’s officers and returned Brown himself to duty.11

Regardless of such leniency due to age, evidence suggests that the youngest soldiers suffered disproportionately from the physical or psychological impacts of war. The overwhelming majority of underage recruits wrote no personal reminiscences, but many left pension files. Modern scholarship based on veterans’ medical records offers a sober counternarrative to the mostly positive accounts left by memoirists like Stanton P. Allen, a former 14-year-old enlistee who later claimed, “The war matured the boys wonderfully.”12 In marked contrast, studies that rely on the Early Indicators database show that war tended to have catastrophic effects on young bodies and minds. Veterans who had enlisted underage were far more likely to experience physical and mental diseases than those who had enlisted in their adulthood. “Mortality risk was significantly associated with age at entry into service,” one study concludes, with the youngest enlistees at “greatest risk for early death.”13

Even the documentation contained in the Early Indicators database probably undercounts the severity of this problem. Pension Office employees who reviewed soldiers’ service histories and medical records apparently understood the relationship between age of enlistment and disability. One scholar notes that they applied a “lower burden of proof” for applicants who had enlisted while still in their teens.14 But many of these veterans never bothered to apply, deterred from seeking help by their comparative youth, or waiting until a medical crisis made an application imperative. A self-confessed “opium eater” who enlisted at 16 and spent time in prison at Andersonville suffered from excruciating stomach pains, headaches, and insomnia, but was dissuaded from applying for assistance by his mother, who thought him “too young.”15 Greater barriers than reticence or pride prevented black veterans of all ages from obtaining pensions. The formerly enslaved had the hardest time, but even those like Isaiah King, who joined the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry (USCT) soon after turning 17, found it impossible to meet the bureaucratic hurdles erected by pension officials. After returning to his hometown New Bedford, King struggled to make ends meet as a laborer; in 1870, he appealed to his local Grand Army of the Republic post for help purchasing coal. “I am not able to do hard manual labor on account of my affliction,” he wrote to his lawyer in 1892. “I do what light work I can get to do which is not enough to support my family[.] I … have a very hard time of it to get along and am very much in nead of healp.” Despite his acute need, it took King 13 years to secure federal relief.16 The many youths who were never officially enlisted but worked for the army in unofficial capacities, often as camp servants or laborers, had little or no hope of making a successful application. They no doubt suffered comparable rates of physical and emotional distress, only with less financial support, than those who left medical records behind.

Early enlistment might also mean losing out on the chance to acquire an education or skills, which could have negative and lasting consequences. Charles L. Cummings, who went to war at 16 and contracted chronic diarrhea, wrote bitterly of his postwar experiences. While he had been off fighting for the nation, his peers had been busy improving their personal fortunes. “I had missed my chance to acquire an education and the other boys had secured the good situations,” he wrote, “and there was nothing left me but the rough work, which I was not fit for.” Eventually, he went to work for a railroad company, only to suffer a dreadful accident that severed both his feet, incapacitating him even further.17 Social histories that trace the postwar lives of Union veterans suggest that enlistment typically had negative financial implications, but whether younger veterans suffered disproportionately remains to be established.18

If a boy survived his service relatively unscathed, however, underage enlistment could prove to be a powerful boost, regardless of how unpromising his start in life had been. Two boys sent by the Children’s Aid Society from New York to Indiana on “orphan trains” in the 1850s enlisted as drummers around the age of 13. Both went on to achieve remarkable success: John E. Butler founded and ran a manufacturing company, while Andrew H. Burke, dubbed the “Drummer Boy Executive” by one newspaper, was elected governor of North Dakota.19 Countless other veterans, including more than 25 men elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, capitalized on their identities as former boy soldiers to run for office or secure government posts. Senator William V. Allen of Nebraska, who had been working as a farm laborer to support his widowed mother when he enlisted at age 15, described his three years in the Union army as “a great experience” and “the better part of my education,” even though he later attended law school. Allen said his service taught him a critical lesson that could not be learned in school—that the true measure of a man had little to do with his social and economic status. “No man” of whatever “pretense or profession” could cause him to feel “fear or awe.”20 Participation in war, in other words, could lead to diametrically opposite outcomes: negative effects for the many but tremendous empowerment for a few.

The impact of underage enlistment on the broader U.S. war effort is more difficult to assess. On the one hand, the presence of so many young soldiers had an enormous bureaucratic and legal impact, as parents wrote to the government demanding the return of sons or filed habeas corpus petitions in local courts to secure their release. Early in the conflict, the War Department was forced to concede to parental demand and discharge any soldier under age 21 who had enlisted without consent. At the start of 1862, however, the rules changed to accept volunteers over 18 regardless of parents’ wishes and, more alarmingly, to hold any enlistee under that age to service if he had lied about his age.

Once administrative avenues for redress narrowed, parents and other relatives increasingly turned to local courts, insisting that the U.S. military release sons who were under 18. In the prewar decades—before the passage of federal laws designed to protect individual rights people looked to state and local courts for day-to-day justice. Such courts regularly adjudicated charges of unjust detention, including impressment by overzealous recruiters. But once the war broke out, local judges had to confront U.S. officers who now insisted that federal institutions, including the military, should be beyond their reach. So it eventually turned out to be: In its 1872 ruling in Tarble’s Case, the U.S. Supreme Court pointed to the plethora of habeas petitions filed by parents during the war as grounds for ending the long-established practice. In the process, the court transformed the writ of habeas corpus from a broadbased right used to challenge detention of all kinds to one used almost exclusively by prisoners seeking to challenge the legality of federal laws. Military encampments would henceforth become walledoff citadels, operating largely beyond community oversight.

"On Wheels and How I Came There" (1893)

"On Wheels and How I Came There" (1893)Union veteran W.B. Smith, who enlisted at 15 in the 14th Illinois Infantry, outlived the war but not the ill effects from his time spent in Confederate prisons. Some boys who survived their war service unscathed used their experience as a boost on the road to personal and professional success. Others survived with war-related disabilities that limited their capacity to work and shortened their lives.

Additional legal implications flowed from underage enlistment at scale. In the prewar years, non-slaveholding households depended heavily on the labor of young men—particularly those between the ages of 16 and 21 who were strong enough to do a day’s work. But military enlistment legally “emancipated” children from parental control. Removing such a large cohort of children from households was economically catastrophic for many—and precisely why parents fought so hard to retrieve their sons. It also accelerated a process underway before the war, in which rights were increasingly vested in individuals rather than in households. Despite young sons’ myriad contributions to families, judges consistently whittled down the concept of parental authority to a question of whether parents or the state held the right to children’s labor.

The fact that government officials did not nip this problem in the bud speaks to the military significance of underage soldiers. They could have responded to parents’ angry letters, petitions, and visits to government offices by simply requiring the army to release any minor who had enlisted without consent. Alternatively, the War Department could have turned a blind eye to local judges who continued to discharge underage soldiers, even after the nationwide suspension of habeas corpus, reasoning that such cases were far different from those filed by adults charged with antiwar activities or seeking to evade the draft. Rather than following either path, officials and Congress crafted policies to thwart the release of underage soldiers and specifically warned judges that the suspension of habeas corpus applied to all petitions. Although protests kept coming from parents, their political representatives, newspaper editors, and others, the War Department never backed down. It could not, because doing so would have meant discharging up to 10 percent of Union enlistees—a prospect even more unsettling than facing down many thousands of enraged parents.

The enlistment of boys and youths probably had additional military implications beyond their sheer numbers, although here only educated guesses are possible. Acknowledging that masses of soldiers had lied on their enlistment papers—with boys adding years and men shaving them off—might, for instance, alter our perspective on camp life. Instead of camps containing a “band of brothers,” they were actually filled with enlistees who spanned generations, ranging in age from boyhood to their 40s and 50s. Fortunate soldiers entered companies that worked a bit like extended families, where older men shepherded younger ones, and camp life was governed for long stretches by familiar household dynamics that included reciprocity and care, cooking and cleaning, mending, socializing, and sharing meals.

The enlistment of so many boys and youths might also have affected battlefield performance in tangible but unverifiable ways. In general, age is arbitrary in the sense that it is often impossible to tell the difference between individuals who are only a year or two apart. But medical advancements since the Civil War have shown that there is a substantial physical, mental, and psychological difference between boys in their teens and those who are even a year or two older. It is also worth bearing in mind that puberty arrived later in the mid-19th century than it does today, such that the Civil War’s underage soldiers were, on average, less physically and mentally developed than males of the same age now. Given these realities, we might speculate that an army containing substantially more young males—more boys—than previously assumed might include more risk takers, or more individuals out to prove something. This was certainly what commentators believed during the Civil War. Many at that time claimed that the war’s youngest soldiers were the most daring and enthusiastic, their spirit helping to fire up their older, more jaded peers.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAn unidentified boy soldier. The Union Army’s underage soldiers—some of whom, as older men, shaped how the war came to be remembered—almost certainly experienced the conflict differently than did their older comrades.

Finally, the presence of masses of soldiers who had been underage when they enlisted probably shaped how the conflict came to be remembered. In the early 20th century, former boy soldiers became the last living links to the war in ways that significantly amplified their voices as representative veterans: In high demand as Memorial Day orators, they were invited to speak to school assemblies, and to publish memoirs about their war years. They were equally prominent in the Grand Army of the Republic: more than half of the last 51 men to head this fraternal order of Union veterans had enlisted underage—a number significantly out of proportion to their share of the overall veteran population.21 While no broad studies or collective biographies of the war’s youngest soldiers exist, it seems reasonable to conclude that they experienced the conflict differently than did older men. They rarely left behind wives and children, trades or professions, so going to war was less likely to conjure anxiety about being able to protect and provide for dependents back home. Because they were more likely to be doted on and protected by mature comrades, and to receive lenient treatment for disciplinary infractions, their experiences may have been on the whole more positive. They may also have been more prone to survivors’ guilt, induced by a sense of indebtedness to men who had helped to care for and essentially raise them. Given that this group came of age amid the militant politics of the 1850s and then enlisted in their youth, it makes sense that they would uphold a vision of the Civil War as a paradigmatic moment of male heroism and cross-generational male bonding—precisely the version of the war that became prominent by the late 19th century.

Underage enlistment mattered, then, for many reasons. Constituting a significant percentage of U.S. forces, young soldiers helped to win the war. They also disrupted households and generated substantial bureaucratic and legal chaos, ultimately resulting in the federalization of habeas corpus. Their antics, impulsivity, and physical limitations influenced the tenor of camp life, while compelling the military to institute what in practice amounted to an informal system of juvenile justice. Above all, underage enlistment proved fateful in shaping individual lives, setting up some for future success and many more for a great deal of suffering down the road.

Frances M. Clarke is an associate professor of history at the University of Sydney, Australia. Rebecca Jo Plant is a professor of history at the University of California, San Diego. Their jointly written book, Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era (Oxford University Press, 2023), was recently awarded the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize.

Notes

1. Thomas Hinds, Tales of War Times: Being the Adventures of Thomas Hinds during the American Civil War (Watertown, NY, 1904).

2. For instance, Bell I. Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (New York, 1953; reprint, 1994), 229, 303; James McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the American Civil War (New York, 1997), viii.

3. For more on our methodology, see Frances M. Clarke and Rebecca Jo Plant, Of Age: Boy Soldiers and Military Power in the Civil War Era (New York, 2023), Appendices A and B.

4. Revised United States Army Regulations of 1861 (Philadelphia: G.W. Childs, 1863), 130.

5. William A. Hammond, “Annual Report of the Surgeon General, U.S.A.,” November 10, 1862, reprinted in Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 67:22 (January 1, 1863): 437–443 (quotation, 442).

6. Charles A. Willison, Reminiscences of a Boy’s Service with the 76th Ohio (Menasha, WI, 1908), 10.

7. Jacob Cole, Under Five Commanders; or, a Boy’s Experience with the Army of the Potomac (Paterson, NJ, 1906), 226.

8. William P. Ellis to Mary Ellis, February 23, 1863, folder “William M. Ellis Correspondence,” box 20, Norman Daniels Collection, Harrisburg Civil War Round Table Collection, U.S. Army War College Library and Archives, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

9. Private W.B. Smith, On Wheels, and How I Came There: A Real Story for Real Boys and Girls, Giving the Personal Experiences and Observations of a Fifteen-year-old Yankee Boy as Soldier and Prisoner in the American Civil War, ed. Joseph Gatch Bonnell (New York, 1892), 47.

10. Frank Wilkeson, Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac (New York, 1887), 4.

11. Court-martial hearing of Henry Brown, April 2, 1864, #LL908 and #NN1795, Record Group 153, National Archives and Record Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C.

12. Stanton P. Allen, Down in Dixie: Life in a Cavalry Regiment in the War Days from the Wilderness to Appomattox (Boston, 1893), 487.

13. Judith Pizarro, Roxane Cohen Silver, and JoAnn Prause, “Physical and Mental Health Costs of Traumatic War Experiences Among Civil War Veterans,” Archive of General Psychiatry 63:2 (2006): 193–200.

14. Ashley Elizabeth Bowen-Murphy, “‘All Broke Down’: Negotiating the Meaning and Management of Civil War Trauma” (PhD diss., Brown University, 2017), 93.

15. Anon., Opium Eating: An Autobiographical Sketch (Philadelphia, 1876), 13, 54.

16. Quoted in Earl F. Mulderink, New Bedford’s Civil War (New York, 2012), 127.

17. Charles L. Cummings, The Great War Relic: A Sketch of My Life, Service in the Army and How I Lost My Feet Since the War (Harrisburg, PA, 1890), 7.

18. Comparing the veteran and nonveteran population in Dubuque, Iowa, Russell L. Johnson, Warriors into Workers: The Civil War and the Formation of Urban-Industrial Society in a Northern City (New York, 2003), chapter 7, suggests that veterans fell behind their civilian counterparts economically.

19. “John E. Butler Dies after Long Illness; Drummer Boy in War,” The News-Herald (Franklin, PA), May 21, 1927; and “The Drummer Boy Executive,” Bismarck Weekly Tribune, January 9, 1891.

20. Albert Shaw, “William V. Allen: Populist. A Character Sketch and Interview,” Review of

Reviews 10 (July 1894): 36.

21. Final Journal of the Grand Old Army of the Republic, 1866–1956 (Washington, D.C., 1957), 35–50.