Library of Congress

Library of CongressUlysses S. Grant—along with Union Generals Samuel W. Crawford and Andrew Porter, and Pennsylvania Governor John W. Geary—is flanked by the boys and girls of Gettysburg’s National Homestead Orphanage during a visit to the establishment in June 1867.

Where do you go when you visit the Gettysburg battlefield? Little Round Top? Devil’s Den? The scene of Pickett’s Charge, or some other recognized site? Three lesser-known stops have priority with me, connected to one another by a twisted narrative thread.

First is Coster Avenue, off North Stratton Street, the smallest parcel of the Gettysburg National Military Park and the site of a monument to the 154th New York Volunteer Infantry, a unit I’ve spent a half-century researching and writing about. The 154th lost 207 of 265 men engaged in the so-called Brickyard Fight on the afternoon of July 1, 1863, a loss rate that was one of the highest among any of the regiments at Gettysburg. And there I also check on the mural my fellow artist Johan Bjurman and I created depicting the battle; it is affixed to the wall of a roofing company abutting the avenue.

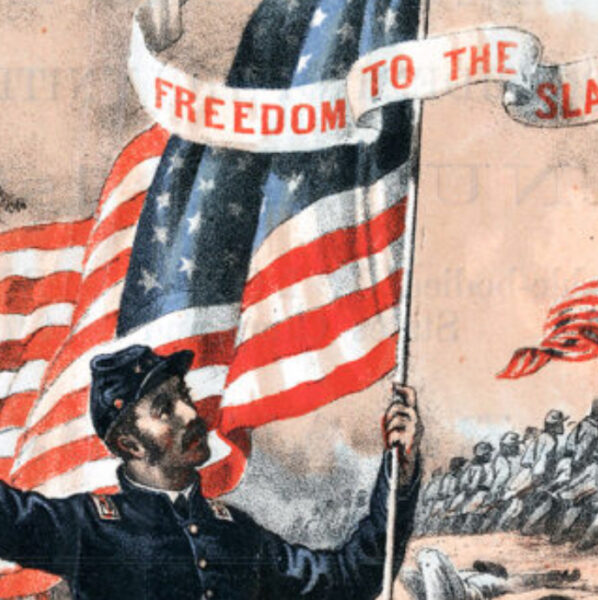

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

Frank Leslie's Illustrated NewspaperAfter the Battle of Gettysburg, word spread quickly of a Union sergeant, Amos Humiston of the 154th New York Infantry, who had died holding an ambrotype of his young children. This illustration from Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper, published in January 1864, is thought to depict Humiston on the battlefield.

Next is a monument on the grounds of the Gettysburg Fire Station on North Stratton Street—the battlefield’s only monument to an individual enlisted man. Sergeant Amos Humiston, 33, of Company C, 154th New York, escaped from the melee at the brickyard and ran up Stratton Street for a couple of hundred yards before falling wounded. As he lay dying, he pulled out a treasure that his wife, Philinda, had sent from home—an ambrotype of their young children, Frank, Alice, and Fred. When his body was found the image was clutched in his hands. The story spread far and wide and led to the identification of Humiston and his family. Today the monument marks the approximate spot where he died.

The memorial was the brainchild of the late Cindy A. Stouffer, who learned the Humiston story in 1991, on a walking tour. The Gettysburg resident was inspired to form and chair a committee that designed the monument, got permission to place it on the firehouse grounds, and linked with people in Portville, western New York, where the Humistons lived when Amos enlisted. For more than a year, plans were made, money was raised, and excitement built in Gettysburg and New York. It culminated when the monument was dedicated on July 3, 1993. I was honored to deliver the ceremony’s main address. At the time, I was working on a book about the Humistons. Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier related in detail Amos Humiston’s life as a civilian and soldier. It also covered the Humiston family’s story after his death.1

And so the thread leads to the third of my Gettysburg must-sees: two buildings on East Cemetery Hill that once housed The National Homestead at Gettysburg (777 and 785 Baltimore Street), an institution said to have been inspired by Humiston’s devotion to his children. It once housed his survivors and others whose fathers had died in the war—and aimed to do good until its quite melodramatic end. I had told the story of the Homestead in my book and, in 1993, Stouffer and her co-author, Mary Ruth Collins, had published a 128-page history of the Homestead. Could anything be added to the historical record of the place?2

Library of Congress

Library of CongressA copy of the photo Humiston was said to have held as he lay dying.

It turns out, yes. In August 2023, Sue Boardman, a licensed battlefield guide, and I led a tour of Coster Avenue and the Humiston monument, during which Sue gave me a photocopy of a letter she had found on eBay. It was written at the Homestead in 1872 by a girl named Ada Lunden, and sent to her mother and younger brother.3 With the letter was a reference to the Ada Jane Lunden letters at the University of Kentucky.4 I contacted Sarah Coblentz at the university’s Margaret I. King Library and was linked to the entire collection online. As I transcribed the Lunden letters, I became absorbed in the story they revealed. They offered an unprecedented look at the Homestead as experienced by a family intimately—and significantly—involved in its history, the Lundens of Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania.

We don’t know when George W. Lunden married Sarah Henry. Evidence in the letters reveals their daughter, Ada Jane, was born on July 27, 1860. Son James was apparently born in 1862. Lunden enlisted in a company raised in Hollidaysburg that was mustered in as Company G of the 125th Pennsylvania Infantry on August 13, 1862. He fought at Antietam and Chancellorsville and survived to be mustered out in May 1863. But he died before the end of the year and before his namesake was born on February 28, 1864. Despite the fact that their father died after his discharge, Lunden’s two older children were accepted at the Homestead, about 100 miles from their home.5

Henry Deeks Collection

Henry Deeks CollectionThe Homestead Association purchased a two-story house on Gettysburg’s Baltimore Pike and enlarged it to three stories in the summer of 1866. A rare photograph depicts workmen during the construction.

John Francis Bourns was a Philadelphia physician and delegate of the United States Christian Commission who returned from volunteering to help treat the wounded at Gettysburg with the ambrotype of the children and initiated the publicity that led to the identification of Amos Humiston and his family. “Bourns” was an affectation—the family name was Burns where he had grown up on a farm near Waynesboro, Pennsylvania. In 1863 he had the time and means necessary to try to identify the soldier and his family.6

Money and sympathy from sales of carte de visite copies Bourns had commissioned of the now-famous Humiston ambrotype began to accumulate. Rev. John Heyl Vincent, a Methodist minister, met Bourns when Bourns came to Portville in January 1864 to give the ambrotype to Philinda Humiston in private and to deliver a speech at a mass meeting at the Portville Presbyterian Church. Vincent also spoke at the church. “Who can tell what may spring from this little incident that has thrilled the heart of the nation?” he asked. “Humiston while dying looked at his children, till a film grew over his eyes, and his hands dropped in death. That last lingering look was a rich legacy indeed. It may lead to the founding of asylums for thousands of orphaned ones over the land.” Bourns told Vincent he had heard an inner voice telling him, “From the father’s last look there may come means to provide for hundreds and thousands of helpless ones.”7

Portville Presbyterian’s minister, Isaac G. Ogden, wrote, “It is the design of the Dr. and his friends in Philadelphia, to turn this most touching incident to a larger account than simply to provide comfortably for the family of Sergeant Humiston. It is hoped that interest enough will be awakened in this subject to secure a fund to aid the families of deceased soldiers all over the land.” He added, “It would be a remarkable illustration of Providence, if from the little ambrotype found in the dead soldier’s hands, should spring a great national charity. Small beginnings often grow to a great conclusion.”8

In September 1865 a new edition of the carte de visite of the Humiston children was issued by a Philadelphia photographer with this notice on the back: “The copies are sold in furtherance of the National Sabbath School effort to found in Pennsylvania an Asylum for dependent Orphans of Soldiers.” Bourns had put his plan in motion. His initial concept was rather grandiose. A poem titled “Gettysburg Song” was issued as a broadside with an illustration of the orphanage’s proposed design, depicting an immense gothic pile. The poem ended, “Where, nobly, they fell, Let their orphan’s dwell.” Could the poet have been Bourns, who envisioned caring for such orphans?9

What resulted was a more modest edifice. The Homestead Association was informally organized in October 1865 to raise money for the proposed institution from Sunday schools throughout the North, and formally organized in March 1866 with a board of directors and an executive committee. In a vote by Sunday schoolers, Gettysburg was chosen over Valley Forge for the site. The Homestead Association purchased about two acres on the northern slope of Cemetery Hill, including a two-story brick house built around 1837 and said to have been Major General Oliver Otis Howard’s headquarters during the battle. The association hired a contractor to enlarge it; meanwhile, Bourns reported that Sunday schools had purchased Homestead shares worth more than $4,300. Any Sunday school that purchased a $25 share was entitled to name an orphan for admission to the Homestead.

The National Homestead at Gettysburg formally opened with fanfare in November 1866. The staff included Philinda Humiston as wardrobe mistress. Frank, Alice, and Fred Humiston, the first children to arrive in Gettysburg, were joined by about 30 others. In 1869 the institution was enlarged with the construction of a three-story, mansard-roofed dormitory. That year Philinda Humiston remarried and left Gettysburg. Her children stayed at the Homestead for a few years, and were there when the Lunden siblings arrived.10

Author's Collection

Author's CollectionThe Humiston children as they appeared during their stay at the homestead.

Ada Lunden was almost 10 when she wrote her first surviving letter from the Homestead on May 11, 1870. It was a rainy day, so the children were confined indoors. Her brother Jimmy, 8, and the other boys were playing “Shinny,” “Pig in the Pen,” and other games. The girls had their afternoon sewing hours. All the children took lessons. If their conduct was good during the week, they were awarded little printed cards with this inscription: “No scholar is entitled to this certificate, who has received a mark of misdemeanor during the week.” Ada enclosed three good conduct cards with her letter. She also sent her mother the love of the Homestead’s superintendent, Professor Charles E. Hilton, and his wife, Elizabeth. And while she asked her mother to visit them, Ada gave no indication that she and Jimmy were homesick. To the contrary, she wrote, “We enjoy ourselves very much.”11

Letters from Sarah Lunden to Ada and Jimmy indicate the rest of 1870 was uneventful; the children enjoyed themselves and had friends. It appears Sarah made a visit to see them, bringing their brother Georgie, 6, with her. Toward the end of the year, Georgie dictated a postscript to one of Sarah’s letters: “I would like to go with you and Jimmy to the Homestead, but Mother says she can’t spare me yet.”12

Sarah’s letters indicate she also received mail from friends of Ada, girls she had met during visits to the Homestead. In April 1871 Ada had some exciting news. “Last Wednesday all the children went to a show and I saw lions and tigers, camels, elephants, monkeys, a kangaroo, and a great many other things.” Sarah hoped that Ada and Jimmy would return to Hollidaysburg for a summer vacation. A correspondence ensued with James Cuthbertson Burns, Dr. Bourns’ brother who served as the Homestead’s steward. Burns was prompt in answering Sarah’s letter, but it seems Ada and Jimmy never left Gettysburg. When fall came, the two resumed sending good conduct cards to their mother. Sarah sent ribbons and feathers for Ada’s doll, small amounts of money and stationery for both children, and poems clipped from newspapers. As the Christmas holidays approached, Sarah sent Ada and Jimmy a box of presents and treats.13

Mary A. Parker Collection

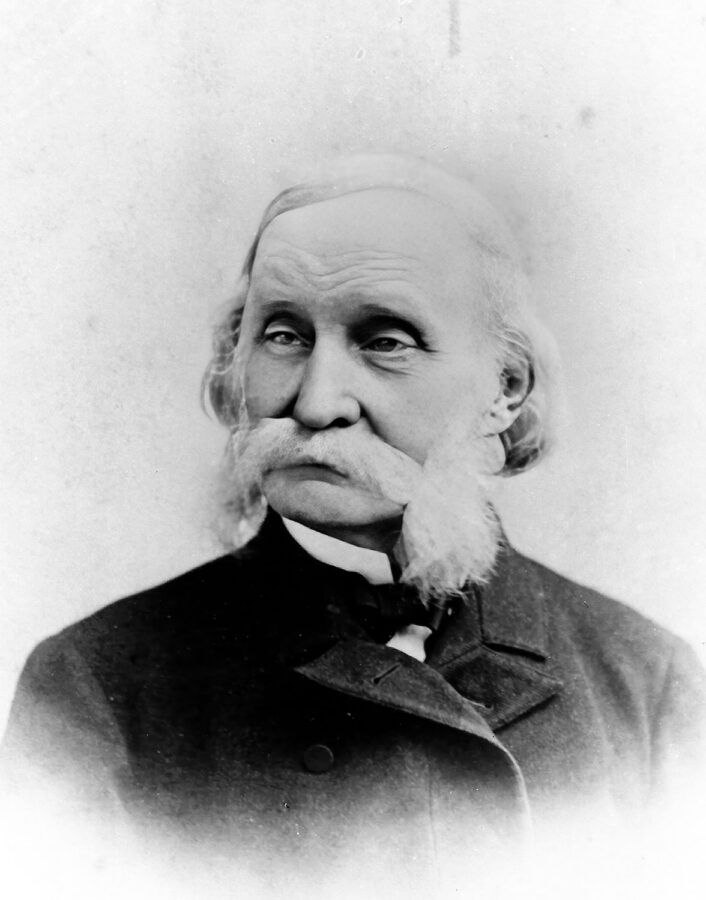

Mary A. Parker CollectionThe only known photograph of Philadelphia physician John Francis Bourns, the driving force behind the identification of Amos Humiston and his family, and the establishment and operation of the Homestead Orphanage.

In February 1872 Ada informed her mother, “Some pleasant evenings Mrs. Carmichael our teacher takes the girls down on the porch and plays with them.” The Hiltons had left the Homestead toward the end of 1870, replaced as administrator by Mrs. Rosa J. Carmichael. Nothing is known of her background, but she was highly regarded by Bourns. “As a teacher and disciplinarian, Mrs. Carmichael has few equals,” Bourns wrote, “and she is a most assiduous and faithful worker, laboring often beyond her strength in school and out.” Bourns’ characterization of Carmichael as an unequaled disciplinarian is noteworthy.14

Sarah Lunden continued to receive good conduct cards sent home by Ada and Jimmy, together with reports of the kind treatment they received from their teachers and of visits by Bourns to the Homestead, which delighted them. In response, Sarah routinely asked the children to “remember me to your teachers and all the children.” Responding to a request from Jimmy that Georgie join them at the Homestead, Sarah wrote, “Oh Jimmy, how could I spare him? I would be so lonely and he is such a good little boy.” Back home, Sarah worked at sewing pants for a local merchant; she repeatedly told them of her desire to travel to Gettysburg to see them, and of her inability to do so.15

The children—of which there were 70 at the Homestead in May 1872—were given small garden plots to tend and in July, Ada reported her flowers were growing nicely, although the flies were a nuisance. She sent home a book James Burns had given her. That September, she noted she was studying history, geography, and spelling, and enjoying her work in the sewing room. The boys were keeping chickens. A planned local balloon ascension had been aborted because of a gas leak. Ada reported that “Mrs. Carmichael and Dr. Bourns took the children out to see Mr. Weaver dig up the remains of the rebels.”16

Dr. Rufus B. Weaver was the son of Samuel Weaver, pioneer Gettysburg photographer who supervised the exhumation of Federal dead on the battlefield so that they could be reinterred at the town’s new Soldiers’ National Cemetery. Following in his father’s footsteps, from 1871 to 1873 Rufus Weaver superintended the exhumation of the Confederate dead at Gettysburg, shipping the remains of more than 3,000 soldiers to cemeteries in the South. Why would Carmichael and Bourns expose the children to such grisly sights? What lesson did they intend?17

After Sarah received that letter, she and Georgie visited Ada and Jimmy. When they returned to Hollidaysburg, Ada wrote, “Mama, please tell Georgie we are waiting for him to come back again…. Mrs. Carmichael desires to be remembered to you and Georgie & she wants Georgie to come back.” For her part, Sarah repeatedly sent her love to Rosa Carmichael and asked to be remembered to Dr. Bourns. On Christmas in 1872, Sarah told the children an aunt had sent them a box of “monkey cards.” “I want you to ask Dr. Bourns or your teachers,” she instructed, “if they have any objections to you playing with them…. We don’t want to send you anything they don’t allow you to have.”18

Author's Collection

Author's CollectionWell-behaved children were presented with good-conduct cards. Ada and Jimmy Lunden routinely sent their cards home to their mother. After receiving this card, Homestead resident Lizzie Hutchinson ran afoul of administrator Mrs. Rosa J. Carmichael, who forced her to wear boys’ clothing for more than two months as punishment.

Georgie continued to pine for his siblings. “He wants to go stay at the Homestead very bad,” Sarah wrote, “but I think I would be very lonely without him.” The Lundens’ relationships with Bourns and Carmichael continued to be good. Sarah planned to send Ada money to have her photograph taken; one picture was to go to Mrs. Carmichael. In 1873, Ada and Jimmy made a summer visit to Hollidaysburg. Georgie was “very lonely” after they returned to Gettysburg, Sarah reported. “He wrote a letter to Mrs. Carmichael. He is expecting an answer to it. He is very proud of the presents she sent him.” When Georgie received a reply from Mrs. Carmichael, he burst with pride at having received a letter addressed to him. The two continued to correspond. “Georgie is well and sends love to his brother & sister & Mrs. Carmichael,” wrote Sarah in the spring of 1874. “Give my love to her too.”19

A few weeks later, Jimmy ran away from the Homestead. “I had a letter from Dr. Bourns,” Sarah informed her son, “stating that your going away from the Homestead cost twenty dollars. Just think of it, Jimmy, your mother had that twenty dollars to pay. But Mother forgives you and I hope you will never do so again.” Whatever had caused Jimmy to run away didn’t stop his mother from finally giving in and delivering little Georgie to join his siblings at the orphanage. Her nest now empty, Sarah was bereft—and it seemed the children were neglecting her. “What in the world has come over you all,” she wondered in February 1875. She hadn’t received a letter for close to two months. When yet another mail arrived without anything from the children, Sarah wrote, “I was so disappointed I could have cried. I just thought, has my little children forgotten me or what is the matter now.” A month later, still having received no word from the boys, she wrote, “I get so lonesome and want to see you so bad I think sometimes I can’t wait any longer. If I could only walk there, you would soon see your mother coming up the pavement. I wonder if my little girl and boys would like to see me.”20

In April Sarah responded to what she deemed the most interesting letter Ada had sent from the Homestead. “I am very much pleased with the presents you made for Mrs. Carmichael,” she wrote. “I think it was so nice for you all to remember her on her birthday, for she is so good and kind, and I think all she had given her was not a bit too good for her and I know you all think that way.” Only two of Sarah’s letters to her children from the rest of the year survive. In September, Sarah closed a letter by sending love “to Mrs. Carmichael and all the boys & girls.”21

William J. Little Collection

William J. Little CollectionAmong the allegations of abuse leveled at Rosa Carmichael was that she had shackled children to the stone walls of the main building’s pitch-black basement. When the Homestead’s household goods were auctioned, Gettysburg’s Grand Army of the Republic Post purchased the notorious shackles, shown here.

The Lundens’ tie to the Homestead was severed in 1876, beginning with Sarah’s marriage. She no longer had to work so hard and felt she had bettered herself, but two months passed and she received no letters from the children. She wondered if they were cross with her for remarrying. Then came two shocks from Gettysburg. On Memorial Day, Rosa Carmichael refused to let the orphans take part in the ceremony at the National Cemetery, where they traditionally had helped Gettysburg’s Corporal Skelly Post, No. 9, Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), in decorating the soldiers’ graves with flowers. With rumors swirling around Gettysburg about goings-on at the Homestead, the veterans already suspected Carmichael of “general misconduct and tyranny.” Their suspicions were confirmed on June 11, when Carmichael was arrested and charged with cruelty to 12-year-old Georgie Lunden.22

Carmichael was released on $300 bail, returned to the Homestead, and resumed her duties. Skelly Post placed Georgie in the protective custody of a local veteran and appointed a committee to investigate various charges against Carmichael. In August a grand jury indicted her on three charges of aggravated assault and battery on Georgie. The prosecutor was absent, so the case was continued to the court’s November term, with Mrs. Carmichael released on $600 recognizance. That fall she was found guilty on the first count of aggravated assault, but not guilty on the second and third counts. She was sentenced to pay a fine of $20 plus court costs, and ordered to leave Gettysburg. She instead returned to the Homestead.23

By then, it appears the Lunden children had been reunited with their mother. Georgie was home with Sarah before Carmichael was indicted. Ada and Jimmy remained in Gettysburg, but not for long. On July 27, Sarah wrote, “Ada, tell Mrs. Carmichael I will come prepared to bring you home with me if I have to come, and if not, I will send for you. Ask her if she will please let me know when the time comes, for I will not like to be at such expense for nothing.”24

Carmichael’s arrest and conviction of assault on Georgie Lunden was one in a series of events that resulted in the Homestead’s demise. The Philadelphia board of directors launched an investigation of conditions at the orphanage, survived a takeover attempt by Bourns, and resolved to shut the Homestead down. A Philadelphia GAR man issued a series of attacks on Carmichael, alleging she had mistreated children with cruel punishments, including confining a child in the outhouse on a cold winter night, forcing a girl to stand atop a desk until she had to be helped down, and forcing girls to wear boys’ clothing as punishments. One teenaged orphan served as her enforcer, beating and kicking accused miscreants. Most notoriously, Carmichael had created a dungeon in the Homestead’s basement, where she shackled children to a wall. Critics alleged the Homestead had become a summer resort for Bourns, where he was waited on by children firmly under Carmichael’s thumb. She had left the Homestead by the time she and Bourns were sued in September 1877 for mismanagement, waste of property, and violation of trust. Bourns was additionally charged with embezzling large sums of money meant for the children. By January 1878 the Homestead had closed, its few remaining children had found new homes, and the institution’s household goods were sold, among them a pair of iron shackles said to have been used by Carmichael. That April the property was sold, and the Homestead orphanage was no more.25

What had happened to Bourns and Carmichael to transform them from people seen as respected benefactors to abusers and crooks? In their book, Collins and Stouffer speculated that a “warped change of personality” was to blame—or were the two bad from the start, crooks in cahoots behind their do-gooder facades. I’ve speculated that Bourns had a Jekyll and Hyde personality. Is it possible that the charges against him and Carmichael were overblown, and the two weren’t as bad as pictured in popular memory? The Lunden collection includes a number of letters Ada received in the post-Homestead years from family and friends, including former Homestead residents Bella Hunter, Angie M. Henning, and Sallie H. Farley. What did they have to say about their erstwhile home in Gettysburg?26

The young women remembered the holidays that offered them welcome “outings” from the Homestead. Decoration Day, the Fourth of July, and Christmas “were our Red-Letter Days,” Farley recalled. She still remembered the songs the children sang in the National Cemetery as they decorated the soldiers’ graves. Without offering details, Hunter indicated the Fourth of July in 1876, which occurred after Carmichael’s arrest, had been memorable. Henning remembered “the last Fourth I spent in Gettysburg, ha ha. Fish and I was in the prison and if we didn’t have some fun.” Henning described herself as an “incorrigible little wretch,” so maybe she was used to stays in the dungeon.27

Each child at the Homestead had been assigned a number. “How I do associate the children with their numbers,” Farley told Ada. “You 78, Jimmie 52, Eddie 33, Angie 103, Millie 125, Frank Humiston 21…. I believe I can remember them all. Often when I wish to remember a number, I will say that was so and so’s number at Gettysburg.” Henning mentioned she had a hankering for some bread and molasses, but “I never indulge in such tempting things since I left the Homestead. I can’t bear the sight of molasses.” It would seem the syrup had been some sort of issue for her at the orphanage.28

Farley’s family corresponded occasionally with James Burns after the Homestead closed, but she hadn’t heard from him in years when he sent her a note in 1888. “He says he is very much changed from what he formerly was. He has had two strokes of paralysis. He cannot walk any distance without a support, and then only for a short distance. I feel so sorry for him.” She remembered him fondly, but not so his physician brother.29

Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress

Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of CongressThe building at 777 Baltimore Street in Gettysburg that housed the Homestead Orphanage, as it appeared in the summer of 2019.

The young women expressed some nostalgia for the orphanage. “We were just wishing today we could get a reunion of all the Homestead scholars who attended at Gettysburg, or as many as could come,” Henning wrote in 1883. On another occasion, she informed Ada, “I would like to see the old Homestead once more, if I did get my daily frogging as Mrs. C used to tell about.” “How I should like to revisit Gettysburg!” Farley declared. “I suppose we would find it very much improved. Although we spent some sorrowful days there, still in looking back I find many bright spots in my life there. What has become of all the children who were there? Some are dead, some are married, and in homes of their own, while others are scattered about here and there through our country. What changes a few years will make!”30

Farley was working as a bookkeeper at Wanamaker’s department store in Philadelphia, where she had occasional encounters with Bourns. “He is getting very old and feeble,” she noted in May 1887. “He called at the store one day to see me. I did not treat him very cordially nor encourage him to come again. He caused Mother very much trouble. She had to resort to law to get us away from Gettysburg and he acted very meanly by her.” Farley remembered that Bourns had promised the children he would take all of them to see the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, but it never happened. “How many promises Dr. B made to us children which were never realized,” she wrote. A month later, she reported, “I saw Dr. Bourns on Chestnut Street last evening. I was so afraid he would recognize me and speak to me that I hurried past. He did not seem very much changed only that his face was very red, and his eyes were bleared looking. I wonder whether he drinks. I hope not.”31

None of the young women knew what had become of Carmichael. “I have never heard from Mrs. Car[michael] and don’t believe I want to,” declared Henning. “I wonder what became of Mrs. Carmichael?” mused Farley. “She was a bad woman, unfit to take charge and have control over children.” History has lost track of Rosa Carmichael, but it records the death of Dr. John Francis Bourns on December 20, 1899, at a state hospital in Norristown, outside Philadelphia.32

EARLY IN THE 20th century the two former orphanage buildings became separate properties. The dormitory (785 Baltimore St.) served for many years as the Homestead Lodging for Tourists run by Stouffer’s co-author Collins. Sisters Rebecca and Ruth Brown purchased the building and in 2015 opened Civil War Tails at the Homestead Diorama Museum. It has become well known for its miniature battle scenes featuring cats as soldiers and sailors. The Browns acknowledge the Humiston and Homestead stories in their establishment and in a book about their work. “We are honored to be stewards of the historic building,” states Rebecca Brown. “It is also our privilege to tell the stories of the National Homestead, whether as a somber reminder of how a good thing can be ruined by one person, or as individual examples of hope.”33

The Browns generally steer clear of the unsavory aspects of Homestead history. Not so their neighbors (777 Baltimore St.) in the original Homestead building. Occupied for many years as a private residence, it was bought in 1957 by the actor and comedian Cliff Arquette, well-known for his stage and TV alter ego, Charley Weaver. Cliff Arquette’s Soldiers Museum opened in 1959. It subsequently changed hands and became the Soldier’s National Museum, with a facade (since removed) that altered its appearance. In recent years the restored building, now owned by Felty Investments, has housed Ghostly Images of Gettysburg, which offers tours that include the basement, where visitors can spend time in Carmichael’s notorious dungeon. On occasion, employees Christina Rowand and Thomas Demko make presentations costumed as Carmichael and Bourns. Both take pride in sharing the history of the Homestead. Both have theories about the characters they portray.34

Demko plays Bourns as “a con man who masked his shallow being and lack of a moral compass while insinuating his intentions were pure and good.” Rowand thinks Carmichael was the alias of a woman who had been severely abused herself (“her treatment of the orphans was learned behavior”), was a longtime acquaintance of Bourns and possibly his lover, and had committed similar crimes prior to her arrival at the Homestead. Rowand sees one benefit to relating the sordid tale: “It will garner national attention to the unspeakable crime of child abuse.”35

Rowand informs me that in 2024 Ghostly Images will be moving across the street to a newly constructed Tour Center, the interior of the Homestead building will be renovated, and her company will offer history tours as well as paranormal tours. As time passes, uses for the former orphanage buildings will continue to change. It seems safe to say that the infamous reputations of Dr. John Francis Bourns and Mrs. Rosa J. Carmichael are perpetual.36

Mark H. Dunkelman of Providence, Rhode Island, has written and lectured extensively on the history of the 154th New York Infantry. he led the drive to erect a monument to the 154th at Chancellorsville and designed the mural at Coster Avenue in Gettysburg that depicts the regiment in action on the battle’s first day. His work was spotlighted in our Winter 2014 issue.

Notes

1. Mark H. Dunkelman, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier: The Life, Death, and Celebrity of Amos Humiston (Westport, CT, 1999), 103.

2. Mary Ruth Collins and Cindy A. Stouffer, One Soldier’s Legacy: The National Homestead at Gettysburg (Gettysburg, 1993).

3. Ada Lunden to Dear Mother and Dear Brother, February 14, 1872. Sue Boardman subsequently sold the letter at cost to the author.

4. 2009ms132.0172: Wade Hall Collection of American Letters: Ada Jane Lunden Letters, 1870–1888, University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center. All the Lunden letters cited below are from this collection.

5. Regimental Committee, History of the One Hundred and Twenty-Fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers 1862-1863 (Philadelphia, 1904), 315 and passim. George Lunden is referred to as London on the regimental roster. He and his son George are both buried (as Lunden) in Hollidaysburg’s Zion Lutheran Cemetery. Michael Farrow, Blair County Historical Society, to author, October 14, 2023.

6. Dunkelman, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier, 133–135.

7. Ibid., 166, 177 n16.

8. Ibid., 166–167.

9. Carte de visite by Wenderoth, Taylor & Brown, Philadelphia, and broadside, “Gettysburg Song,” Bryson & Son, Printers, 2 North Sixth St. (Philadelphia), both in author’s collection.

10. Dunkelman, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier, 179–195.

11. Ada Lunden to her mother, May 11, 1870; Collins and Stouffer, One Soldier’s Legacy, 43–45; National Homestead at Gettysburg good conduct cards, author’s collection.

12. Sarah Lunden to Ada and Jimmy, June 13, August 14, and December 11, 1870.

13. Sarah Lunden to Ada and Jimmy, February 16 and October 23, 1871, January 23, 1872; Sarah Lunden to Ada, April 2, May 15, and July 17, 1871; Ada Lunden to her mother, April 26 and September 27, 1871.

14. Ada Lunden to her mother, February 11, 1872; Dunkelman, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier, 200.

15. Sarah Lunden to Ada and Jimmy, March 18, April 6, April 22, April 29, May 21, and July 1, 1872.

16. Ada Lunden to her mother, July 23 and September 4, 1872.

17. William A. Frassanito, Early Photography at Gettysburg (Gettysburg, 1995), 48, 400–402.

18. Ada Lunden to her mother, October 2, 1872; Sarah Lunden to Ada and Jimmy, November 3, December 25, 1872.

19. Sarah Lunden to Ada and Jimmy, February 28, April 14, June 16, August 28, September 22, October 13, December 8, 1873.

20. Sarah Lunden to Ada and Jimmy, May 26, November 12, 1874, February 18, March 3, March 29, 1875.

21. Sarah Lunden to Ada, April 15, June 18, 1875; Sarah Lunden to her children, September 1, 1875.

22. Sarah Lunden to Georgie, February 17, 1876; Dunkelman, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier, 201.

23. Dunkelman, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier, 201; Collins and Stouffer, One Soldier’s Legacy, 63–64.

24. Sarah Henry to Ada and Jimmy, July 27, 1876.

25. Dunkelman, Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier, 201–208; Collins and Stouffer, One Soldier’s Legacy, 64–81.

26. Collins and Stouffer, One Soldier’s Legacy, 67; Errol Morris, Seeing Is Believing: Observations on the Mysteries of Photography (New York, 2011), 249.

27. Sallie Farley to Ada Lunden, June 9, 1887, May 29, 1888; Bella Hunter to Ada Lunden, July 20, 1879; Angie Henning to Ada Lunden, August 26, 1882.

28. Sallie Farley to Ada Lunden, May 10, 1887; Angie Henning to Ada Lunden, August 26, 1882.

29. Sallie Farley to Ada Lunden, June 9, 1887, May 29, 1888.

30. Angie Henning to Ada Lunden, December 23, 1883, and July 12, year unspecified; Sallie Farley to Ada Lunden, April 1 and June 9, 1887.

31. Sallie Farley to Ada Lunden, May 10 and June 9, 1887.

32. Angie Henning to Ada Lunden, November 12, year unspecified; Sallie Farley to Ada Lunden, May 10, 1887.

33. Collins and Stouffer, One Soldier’s Legacy, 95; Ruth and Rebecca Brown, Civil War Tails: 8,000 Cat Soldiers Tell the Panoramic Story (Guilford, CT, 2018), 6, 49; Rebecca Brown to author, December 27, 2023.

34. Collins and Stouffer, One Soldier’s Legacy, 93–96; author’s interviews with Christina Rowand and Thomas Demko, August 19, 2023.

35. Christina Rowand to author and Thomas Demko to author, both December 15, 2023.

36. Christina Rowand to author, December 15 and 22, 2023.