Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn this painting by Thure de Thulstrup, Union soldiers advance past the Dunker Church at the Battle of Antietam.

On September 21, 1862, four days after the Battle of Antietam, Colonel James W. Jackson, commanding a brigade in Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s command, wrote his wife, “You asked me why Col. Oliver resigned. I don’t think he was fond of the smell of burned gun powder & the rattle of shell grape & ball. Battle is a terrible thing and it takes nerves of iron to stand the battles we are having in this country.”

In describing the fighting he had experienced at the Sunken Lane, Sergeant Francis Galwey, of the 8th Ohio Infantry, wrote, “We had seen a great deal of service before now; but our fighting had been mostly of the desultory, skirmishing sort. What we see now looks to us like systematic killing.” Soldiers like Jackson and Galwey had seen combat before Antietam—on the Virginia Peninsula, in the Shenandoah Valley, and in northern Virginia during the Second Manassas Campaign. But there was something about Antietam that shook men hardened by battle on other fields. It brought home that they were in for a long, grim war with a bellyful of burned gun powder and the rattle of shell, grape, and ball.1

Alabama Department of Archive and History, Montgomery

Alabama Department of Archive and History, MontgomeryJames W. Jackson

We know quite a bit about the generalship at Antietam—a battle generally recognized as a strategic Union victory but a tactical draw, on whose iconic terrain (Burnside Bridge, the Sunken Lane, the East and West Woods, the Cornfield, the Dunker Church) happened the bloodiest single day of combat in American history, with some 23,000 troops killed, wounded, or captured—but considerably less about what soldiers like Jackson and Galwey experienced. Their battle was radically different from that of the generals who commanded the opposing armies, Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan. To better understand it we need to narrow our focus from the broad view of the commander to the intimate one of those who executed the orders; to move from the rear to the front where we can see even the features on the faces of battle.

On the night before, everyone involved, from tested veterans to raw Confederate conscripts and Union volunteers, was prepared for a great set piece battle the next day. The prospect of impending death prompted grave reflection. Sergeant Galwey recalled how, in the bivouac of his II Corps division, “everything became terrifically quiet, for the quiet that precedes a great battle has something of the terrible in it.” Many soldiers sought comfort in their religious faith. Corporal Sebastian Duncan, 22, whose 13th New Jersey Infantry had formed only three weeks earlier, wrote in his journal: “My earnest prayer is that I may do my duty. I am willing to leave [it] in God’s hands. If I come through safely I shall thank Him. If killed I hope I am prepared to meet Him.” Sergeant Ben Milikin, with the 27th Georgia Infantry of D.H. Hill’s division and stationed near the Sunken Lane, found a different means of coping. He and some comrades discovered several kegs of hard cider on a nearby farm with the result that “the first thing I knew I was so drunk that I was afraid I could not get back to the regiment.” Captain Francis E. Pierce, 108th New York Infantry, wrote that in his regiment there was little sleep because they were constantly awakened to receive ammunition, rations, “or something.” In the 132nd Pennsylvania Infantry, Adjutant Fred Hitchcock was ordered by his colonel, Richard A. Oakford, to prepare a complete roster of all who were present, “for, said he, with a smile, ‘We shall not all be here tonight.’”2

Heat, cold, rain, wind, snow, hunger, fatigue—the universal conditions that can affect a battle’s circumstances, its outcome, and how an individual soldier perceives his experience. The Battle of Antietam took place in September. It was 65 degrees at 7 a.m. and would rise to 74 by 2 p.m. It had rained lightly in the early morning, although many soldiers were so preoccupied with the impending battle, or so fatigued by the marching and fighting they had done in recent weeks, that they made almost no mention of this in their post-battle writings. While there were Union soldiers who were hungry or fatigued when the battle opened, they were in good shape compared with their counterparts in the Army of Northern Virginia. When Lee invaded Maryland on September 3, he had gambled that his army could purchase provisions from local communities and farms. But Marylanders proved unwilling to accept the currency or receipts from the invaders, and Lee was reluctant to seize supplies since he wished the state’s residents to accept his army. The result was that Lee’s men went hungry and straggling became epidemic. Further aggravating their condition was that units in Lee’s army had been in the field for months. Uniforms were ragged, transportation was sparse—which meant the men lacked shelter tents— and provisions were perpetually short, contributing to sickness and exhaustion. A soldier in the 3rd Alabama Infantry wrote home on October 18 describing his plight: “I am shoeless and ragged. Nothing to supply my necesaties can be got up here. I am at a loss to know what to do. Numbers are in my fix.” Rufus Collins, 31, a miller serving in the 18th North Carolina Infantry, wrote home: “I am almost run to death and starved for water and sompin to eat and when I git water its mud and when I get my rations it is not fit to eat and when I git to lye down I have to ly on the ground.” Captain Robert W. Withers, 42nd Virginia Infantry, recalled that at Antietam he was “broken down from loss of sleep and forced marching,” and “therefore paid little attention to details, and cared but little whether we lived or died.”3

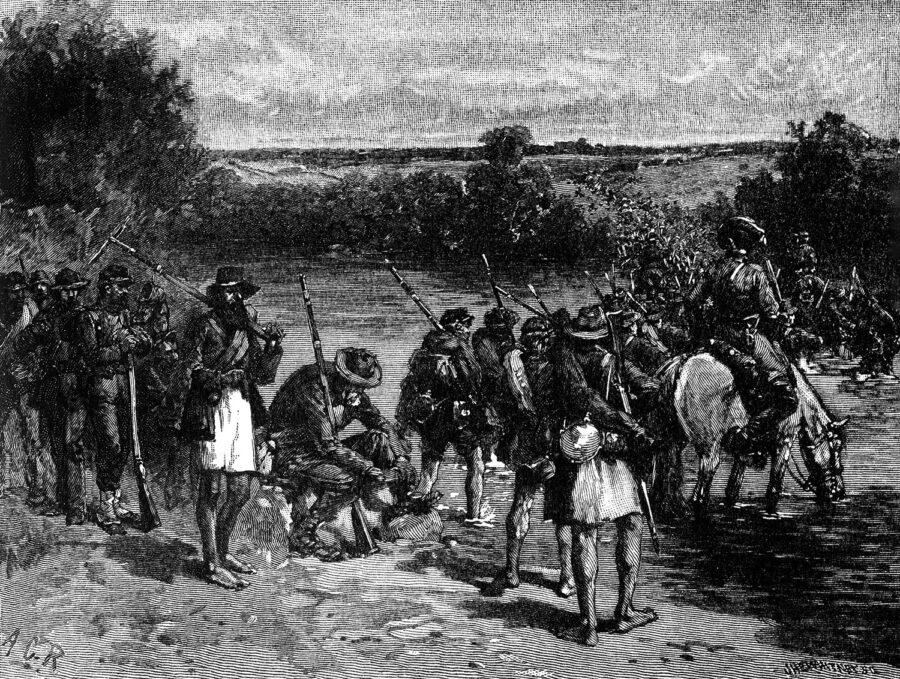

Battles and Leaders of the Civil War

Battles and Leaders of the Civil WarUnlike their Union Army counterparts on the day of the Battle of Antietam, Robert E. Lee’s soldiers were generally fatigued and hungry from their recent forced marches and inadequate supplies. Above: Lee’s haggard Confederates are depicted, in a postwar illustration, crossing the Potomac River during the Maryland campaign of 1862.

The battle opened around 5:30 a.m. to the roar of artillery, which rapidly spread along nearly all the 3-mile front between the armies. The big guns drew first blood. The third shell fired by a section of Lieutenant Asher W. Garber’s Staunton (Va.) battery, a percussion shell, landed amid Company A of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry, whose men were hurrying to get cover, and killed or wounded 13 of them; one man lost both arms and the company commander lost a foot. Artillery had two primary roles on a Civil War battlefield. One was to engage enemy artillery—either to silence it, to support an infantry assault, or to draw its fire away from friendly infantry. The other was to sow terror and demoralize the enemy. It did not take many shells like the one that hit the 6th Wisconsin to affect morale. The experience of Brigadier General Harry Hays’ Louisiana brigade offers another example. Early in the fighting Hays’ Confederates moved out of the East Woods to a point south of the Cornfield to support Colonel Marcellus Douglass’ Georgia brigade. Here they came under terrific artillery fire, both from 20-pounder Parrot rifles across Antietam Creek, and from I Corps batteries to the north. William P. Snakenberg, a 14th Louisiana Infantry private, wrote how one shell that landed near him wounded three men, and another that struck to his left killed or wounded 13. In the 5th Louisiana Infantry, Captain Fred Richardson was lying beside Lieutenant Nick Canfield in the rear of their company. Canfield’s brother, William, was lying directly in front of him. A shell struck that went through William’s body, “then cut off the leg of John Fitzsimmons, then both feet of D[avid] Jenkins, and passed through my poor friend Nick, entering at the small of the back, coming out of his breast.” In an instant four men were dead or dying in a welter of blood and gore. Such shocking incidents could quickly sap a unit’s will to fight.4

An oft-repeated statistic is that small arms inflicted 90 percent of all casualties in Civil War battles and artillery about 10 percent, with less than 1 percent from bayonets, clubbed muskets, etc. Though these figures are derived from The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion—a comprehensive, multivolume postwar study of Civil War wounds and disease—there is reason to question them. Some battlefields, such as Antietam and Gettysburg, were more deadly from artillery fire than were battles like the Wilderness or Chickamauga, because of superior fields of fire. Also, surgeons generally did not differentiate among wounds inflicted by a smoothbore musket ball and shrapnel or a canister ball. What percentage of casualties did artillery inflict at Antietam? We cannot know for certain, but anecdotal evidence suggests it was considerable.

Artillery played a significant role in every phase of the fighting. On the northern part of the battlefield—the area encompassed by the East and West Woods and the Cornfield—the Federals established such a concentration of guns extending from the front of the East Woods to Poffenberger Hill that no Confederate unit could survive in the open ground between. The soldiers who attempted it, such as the men of Colonel Vannoy H. Manning’s brigade, who in midmorning attacked out of the West Woods onto the Dunker Church plateau, quickly learned. The 48th North Carolina Infantry, the largest regiment in Manning’s brigade, after crossing Hagerstown Pike were subjected to a deluge of shrapnel and canister that killed and wounded many. The survivors, despite the strenuous efforts of their officers, broke and fled back into the woods. In the opinion of the regiment’s lieutenant colonel, Samuel H. Walkup, Union artillery fire “swept everything before it.”5

Union soldiers who carried the Sunken Lane had a similar experience when they tried to advance beyond it to exploit their success. Here, the Union high command failed to provide Major General Israel Richardson’s II Corps division with the artillery support it needed to silence the Confederate batteries assembled along Reel Ridge, west of Hagerstown Pike. The result was Richardson’s brigades could not survive in the open ground near the Henry Piper farm.

In an instant four men were dead or dying in a welter of blood and gore. Such shocking incidents could quickly sap a unit’s will to fight.

VLW Cartography

VLW CartographyThe Battle of Antietam was fought outside the town of Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862, pitting Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia against George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. The fighting opened at dawn and ended by about 5:30 p.m., and consisted of a series of attacks and counterattacks, beginning on the Union right (north of town) before shifting to the Union left. While outnumbered, Lee’s army held—aided by the timely arrival of reinforcements from the south in the form of A.P. Hill’s division—with the battle ending in what historians generally recognize as a strategic Union victory but a tactical draw. By nightfall, Union and Confederate forces had suffered nearly 23,000 casualties combined, making Antietam the single bloodiest day in American history.

Skirmishers and sharpshooters were present at all points on the battlefield. Typically, a regiment or brigade would deploy one or two companies as skirmishers, to precede attacking formations or screen defensive positions. Colonel Marcellus Douglass, for example, covered the front of his Georgia brigade, positioned just south of the Cornfield, with two companies commanded by Lieutenant William H. “Tip” Harrison. The skirmishers deployed in extended order. The tactical manual called for at least 5 feet between each man, although the actual distance varied with the situation on the ground and the cover available. Harrison’s skirmishers concealed themselves in the Cornfield and around the David Miller farm, which was almost 700 yards in advance of Douglass’ main line. Their mission was to engage any Union skirmishers and provide Douglass with warning of an attack. Hollywood filmmakers have nourished the belief that soldiers in the opposing armies stood in the open to engage one another. But Harrison’s skirmishers were not visible to the men of Company I, 6th Wisconsin Infantry, the Union skirmishers who advanced on them from the North Woods. The Rebels’ positions around the Miller farmhouse were only revealed when they began to fire at the Midwesterners and smoke from their rifles gave away their location. Captain John Kellogg, a resourceful officer commanding Company I, led his men “at a run” across a plowed field that separated the North Woods from Miller’s farmyard, and by a “rapid flank movement handsomely executed,” forced the Georgian skirmishers to abandon their position and dash back into the corn. This particular tactic—employing fire and rapid movement—was something a soldier in America’s wars of the subsequent two centuries would have recognized.6

While skirmishing was like the first raindrops before a storm’s deluge, sharpshooters were a battle’s lightning strikes. Although there were designated units at Antietam, such as the 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters, the typical sharpshooter was a skirmisher who was a skilled shot. Officers were their favorite targets and a single marksman could wreak havoc on an enemy’s command and control. Having first scaled a tree in the East Woods, a 4th Texas Infantry sharpshooter shot the horse of Colonel George Beal, commanding the 10th Maine Infantry. When Beal dismounted, the sharpshooter shot him through the thigh—and the injured horse smashed into the mount of the regiment’s lieutenant colonel, knocking him from his saddle. Back on his feet, Beal was kicked in the stomach by his horse, taking him out of the battle. In short, two Confederate bullets gutted the command of the 10th Maine. Confederate sharpshooters from the 4th Alabama Infantry also destroyed the command of the rookie 128th Pennsylvania Infantry. Henry A. Shenton, a 17-year-old private, recalled that as he and his comrades advanced from the northwestern tip of the East Woods, he saw a puff of smoke rise from a tree “about a hundred yards to our left” moments before the regiment’s colonel, Samuel Croasdale, toppled from his horse, shot in the head. Lieutenant William W. Hammersly, who dismounted and ran to Croasdale, was immediately shot in the wrist. After this, Major Joel B. Wanner dismounted, “else the enemy’s sharp shooters would have picked him off,” observed Private Peter Noll. A lieutenant in the regiment cut off his shoulder straps and picked up a musket to conceal his rank. “The rebels try to pick off the officers,” Noll noted. Union sharpshooters were just as deadly. Brigadier General Lawrence O. Branch, commanding one of A.P. Hill’s brigades, made the fatal mistake late in the day of being in an exposed position when he raised his field glasses to study the Union lines. A moment later a bullet, from a rifle probably 300–400 yards away, hit him in the head and killed him.7

National Archives (Mansfield); USAHEC (Williams)

National Archives (Mansfield); USAHEC (Williams)Joseph Mansfield Jr. (left) and Alpheus Williams

The skirmishing ultimately gave way to a great clash of infantry in line of battle. This formation was two ranks deep, shoulder to shoulder, with a thin line of lieutenants and sergeants strung out in the rear to serve as file closers. It has long been misunderstood why Civil War soldiers fought in this formation instead of in the dispersed order of skirmishers. Very simply, a line of battle had far greater firepower than a skirmish line and was easier to command and control. That said, moving troops in line over any distance was inefficient because the presence of fences, crops, farm buildings and other such obstacles disordered and slowed various parts of the line. So both armies moved their units to the edge of the battle in column, usually a formation of four men abreast; numerous Union units, however, particularly in the XII Corps, employed extremely dense formations known as column of companies or double column of companies. In these instances a company or two companies, side by side, would deploy in line and the other companies of the regiment would form directly behind them, stacked one behind the other so that a regiment resembled a Greek phalanx. It made command and control simple—but if it came under artillery fire could result in catastrophe. Major General Joseph Mansfield Jr., commanding the XII Corps but who had had no experience in the tactical handling of troops under fire, ordered all his regiments to approach the fighting in either column of companies or double column of companies. When they came under artillery fire, his second in command, Brigadier General Alpheus Williams, an experienced soldier, begged Mansfield to deploy the regiments to line, “in which the men present but two ranks instead of twenty.” But Mansfield refused, fearing that the men in his newly raised regiments would run away in terror. When Mansfield was mortally wounded minutes later, Williams’ first order of business was to deploy all his regiments into line.8

No one gave a better description of the lethality and confusion of the clash of infantry at Antietam than Major Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry. After advancing hundreds of yards across plowed ground—through Miller’s garden, farmyard, and 30-acre cornfield, all while under artillery fire and small arms fire from unseen Rebel skirmishers—the 6th emerged into the meadow south of the corn and came face to face with Douglass’ Georgians, who were lying behind a fence line about 150–170 yards away. The Georgians, warned by their skirmishers of the Federals’ approach, rose up. Both sides opened fire simultaneously. Dawes wrote: “Men … were knocked out of the ranks by dozens. But we jumped over the fence, and pushed on, loading, firing, and shouting as we advanced. There was, on the part of the men, great hysterical excitement, eagerness to go forward, and a reckless disregard of life, or every thing but victory.” Every soldier’s experience at Antietam was his own, but there are aspects of what Dawes describes that were common that day. Despite the range, many bullets found their targets, knocking men over by the dozens. This occurred at numerous points on the field, almost always when soldiers stood up while firing or when they came upon the enemy unexpectedly and had no opportunity to take cover. While infantry needed to be in line to achieve a concentration of fire, if the line had no cover their casualties piled up quickly. Nearly 150 men went down in the 4th New York Infantry—a quarter of its strength—in the very first volley delivered by Confederates in the Sunken Lane. In most, but not all, instances, when a line came under fire, its members lay down or knelt to deliver their fire. Again, this does not accord with Hollywood’s cinematic framing of how Civil War soldiers fought, but in most engagements at Antietam, men tried to find cover or reduce their target size.9

Antietam National Battlefield

Antietam National BattlefieldAt Antietam, as at most Civil War battles, soldiers took cover whenever possible. That did not spare their regiments from taking heavy casualties, as happened during fighting at the sunken lane, here depicted afterward by James Hope, a professional painter and Union captain who had acted as a scout and mapmaker during the battle.

In one of the more remarkable firefights of the battle, the 27th Indiana and 3rd Wisconsin infantry regiments shot it out with regiments of Roswell Ripley’s and Alfred Colquitt’s Confederate brigades, from a slightly elevated ridge north of the Cornfield. While the Confederates had some cover from a rail fence and concealment from the corn, the two Union regiments were completely exposed. Unusually, as Edmund Brown of the 27th Indiana observed, everyone in the regiments remained standing throughout the fight. The carnage Brown witnessed was appalling. “Everyone that the eye rests upon, even for a moment, is seen to fall,” he wrote. “A soldier makes a peculiar noise in loading his gun, which attracts attention, but when we turn to look at him he falls. Another makes what he considers a good shot, and laughs over it. When others turn to inquire the cause, he falls. A third turns to tell the man in the rear rank not to fire so close to his face. Others glance in that direction, only to see both fall. All of these instances, and others, are observed by the writer at almost the same moment.”10

Sometimes lying down or having some cover did not save units from heavy casualties. Though the men of Captain William Houghton’s company of the 14th Indiana Infantry were lying down while fighting at the Sunken Lane, Houghton wrote that “grape & canister, shot & shell screamed & whistled over us & around us till the air was dark and destruction seemed to stalk with undisputed sway. I saw my brave boys fall like sheep led to the slaughter. Bryant was shot through the brain. MCord was shot near the heart, & while the life blood was gushing from the wound he sat up and with an almost heavenly smile playing in his features, he told us he was dying but to mind him not—he was happy and we must go and avenge his death. ‘Farewell Boys! Farewell Captain’ he exclaimed as I reached [for] him and [he] fell forward on the earth.” B.B. Ross, a private in the 4th North Carolina Infantry, wrote that in the Sunken Lane it was “certain death to leave the road, wounded, as the balls fly so thick over us,” and that it was dangerous to rise even momentarily to pass an order along the line. Ross had to do so during the battle and the third time he rose up he was wounded.11

Rufus Dawes described a great, hysterical excitement— and a reckless disregard for life—among the men of the 6th Wisconsin. Numerous soldiers related similar experiences. Combat could provoke a recklessness that transcended logic and reason. Frank Holsinger, with the 8th Pennsylvania Reserves, recalled when he saw members of Evander Law’s brigade of John Bell Hood’s Confederate division start to retreat under terrific fire how he and his comrades cheered; “we are in ecstasies. While shells and canister are still resonant and minies sizzling spitefully, yet I think this is one of the supreme moments of my existence.” Dawes and Holsinger reveal an unsettling reality of Civil War combat, that for all its horrors and dangers, soldiers could be driven to such a frenzy that the destruction of their enemies brought a certain pleasure and euphoria.12

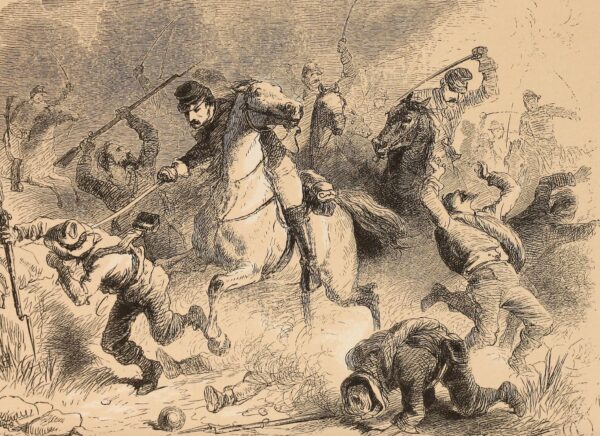

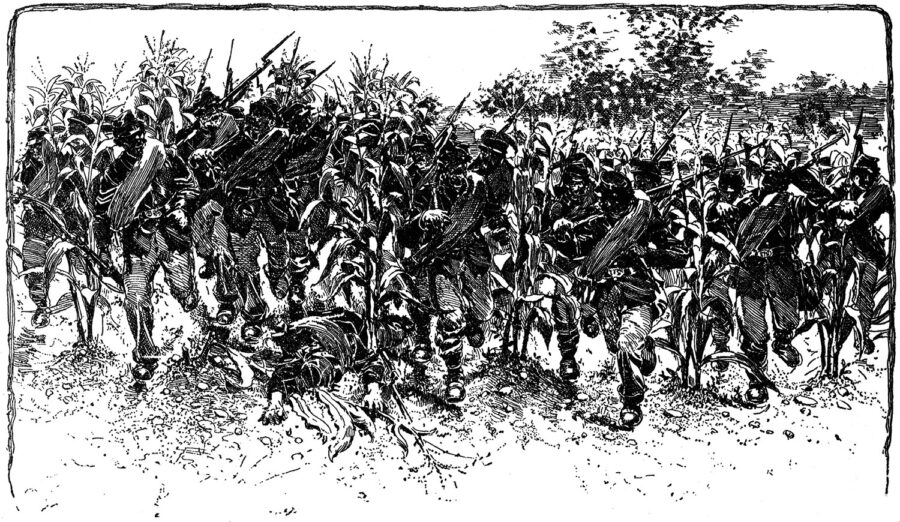

Battles and Leaders of the Civil War

Battles and Leaders of the Civil WarThe Battle of Antietam witnessed many incidents of courage, with men on both sides displaying a willingness to sacrifice their lives for their comrades. Above: A line of stalwart Union soldiers rush through the cornfield toward the enemy, as depicted in a postwar illustration.

Incidents of courage were common at Antietam. Many involved color bearers who, besides mounted officers, had the most dangerous job of any soldier. Flags were not just banners for inspiration, they were a means of communication and a point upon which soldiers could guide their movements through the confusion and black powder smoke of combat. It took a brave man to carry the flag since it attracted a great deal of enemy fire. When a reinforcing Confederate brigade accidentally fired into the 4th North Carolina Infantry in the Sunken Lane, Lieutenant Franklin H. Weaver, 22, with astounding bravery, stood up with the colors of the 4th to identify his unit. He saved his comrades from another volley of friendly fire, but Weaver was immediately shot and killed by a Union soldier. It is impossible Weaver did not understand the risk he took to save his comrades. Holsinger remembered his regiment’s color bearer, Corporal George Horton, as the “bravest of the brave.” He had been shot through the arm at South Mountain three days earlier, and merely tied a bandage around the wound. When someone asked why he did not go to the hospital, Horton replied, “When I go to the hospital, I will have something to take me there,” and added that fateful statement of many a brave man: “The bullet has not been moulded to kill me.” In desperate fighting against Hood’s men in the northwest corner of the East Woods at Antietam, Horton was shot in the ankle. Rebel soldiers closed upon them bent on capturing his flag. When someone shouted for Horton to relinquish the banner, he answered, “Stay and defend them.” In the melee that followed Horton died defending his regimental colors. For the mass of men who were frightened and shrank from the danger in front of them, the Weavers and Hortons of the armies, despite the mortal cost of their courage, inspired many of lesser bravery to do their duty.13

For every George Horton and Franklin Weaver at Antietam there was a Colonel William H. Christian or a Private Joseph Frame. Christian and Frame were among those whom the battlefield paralyzed with fear. A soldier in the 4th Alabama Infantry, Frame was a strapping fellow, 6 feet, 2 inches tall, and around the campfire claimed he could whip any three soldiers, but had a reputation in the regiment as a “downright coward” who became “perfectly demoralized at the first sound of a bullet or shell.” When the 4th went into action at Antietam, emerging into the open from the West Woods around the Dunker Church, Frame dropped to all fours. His lieutenant, who had vowed to kill him if he shirked, seized Frame by the collar and tried to haul him forward but Frame stubbornly held his ground. The lieutenant did not kill Frame, but gave him a hard kick and hurried after the regiment. Frame remained with the regiment until October 1863, when he was captured in Tennessee; he took the oath of allegiance in June 1865. Christian, commander of the 26th New York Infantry, was what today might be called a good “garrison soldier”—someone who excelled at soldiering in camp and on the drill field. He had served as an enlisted man in a volunteer regiment during the Mexican War, seeing no combat, and as a drillmaster for the New York State Militia before the Civil War. But the battlefield terrified him. By seniority, Christian was a brigade commander in Brigadier General James Ricketts’ I Corps division. During their advance toward the East Woods and Cornfield under sporadic artillery fire, Colonel Christian gave a series of contradictory orders before he was seen to dismount from his horse and start toward the rear, ducking and dodging his head with each shell burst, abandoning his men—and ending his military career. Christian was allowed to resign his commission two days later. Instead of demoralizing his men, they expressed disgust at their commander’s behavior. An enlisted man like Frame could be tolerated but the standard was different—and higher—for an officer and Christian could not be allowed to remain.14

Sam Hodgman, a lieutenant in the 7th Michigan Infantry, had two soldiers like Frame in his company. He decided that at Antietam they would do their duty. Hodgman placed his sword at the back of one of them and literally drove him toward the enemy. As the 7th pressed forward during its division’s ill-fated advance toward the West Woods, the one soldier, who had swallowed his chewing tobacco to make himself sick, started vomiting. Hodgman had no sympathy and “by close watching & sundry threats, I got them to face the music,” he wrote. In the ensuing desperate combat, one man was killed and the other badly wounded in the thigh. Hodgman too was wounded. He felt no regrets about driving the two men to their fates. “Had it not been for me one would probably have saved his life and the other preserved his leg unhurt—however my conscience does not accuse me of murder,” he wrote his father.15

Union general John Gibbon, who commanded a brigade at Antietam, once wrote, “none but fools, I think, can deny that they are afraid in battle.” The key was managing your fear to do your duty. Edward Spangler, a young private in the rookie 130th Pennsylvania Infantry, was representative of those who did so. As his regiment approached the Sunken Lane with bullets whizzing through the air “thicker than bees” and shells bursting with “a deafening roar,” Spangler admitted that he was seized with fear: “I hugged the plowed ground so closely that I might have buried my nose in it. I thought of home and friends, and felt that I surely would be killed, and how I didn’t want to be!” The moment he first discharged his rifle, the fear began to dissipate; soon he found that “the excitement of the battle made me fearless and oblivious of danger.”16

What of the survivors’ unseen wounds after a bloody engagement like Antietam? Five days after the battle a shaken H. Waters Berryman, 1st Texas Infantry, wrote his mother, “Oh! Ma, you never saw such destruction of human life.” Lieutenant Henry Ropes, with the 20th Massachusetts Infantry, declared in a letter to his brother, “It was really a most awful sight. The dead were really piled up and lay in rows.” A 2nd Massachusetts Infantry soldier who walked over part of the field on September 19 wrote in his diary that it was “too much for me to describe,” adding that he hoped “it will never fall to my lot to witness such an awful scene again.” Private Austin Carr, 82nd New York Infantry, had to bury his best friend, who had been killed in the West Woods. Carr wrote that the burial caused him to come undone; “tears gushed down my face in spite of all my efforts to stop them, & so I bid him good-bye & left him there to sleep. The bitter wound in my heart to last forever.” It is tempting today, with our awareness of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), to imagine that multitudes of men who survived Antietam afterward suffered from this affliction. The emotional trauma from exposure to horrifying events in combat may result in PTSD, a disorder than can be long lasting, but for many Antietam survivors who left a written record of their mental state after the battle, their nerves gradually recovered and they resumed normal duties. Numerous soldiers related being sick after the battle, suffering severe headaches, mental confusion, physical prostration, shaken nerves, and the like but gradually they recovered.17

And while a soldier might recover to perform his duties, such a searing and shocking event like the Battle of Antietam was never effaced from memory. Survivors simply learned to live with all they had seen. Philip Plumb, a soldier in the 8th Connecticut Infantry, who also had to bury a friend killed during the fighting, reflected on this in a letter home: “Such are the fortunes of war and we are obliged to accept them.”18

What men who experienced the worst of Antietam did not see was glory. Few wrote of victory or defeat. Most simply marveled at their survival and attempted to process what they had gone through. They would have concurred with Captain John Whiteside, 105th New York Infantry, who wrote his mother on October 4, 1862: “Some of us overtaxed our physical powers, so that we did not get over that day’s hardships yet, and many of us, yes very many of us will never get over it until death overtakes us.”19

D. Scott Hartwig, former supervisory park historian at Gettysburg National Military Park, retired in 2014 after a 34-year career at the National Park Service. He is the author of To Antietam Creek: The Maryland Campaign From September 3 to September 16 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012) and I Dread the Thought of the Place: The Battle of Antietam and the End of the Maryland Campaign (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2023).

Notes

1. James W. Jackson to My Dear Wife, September 21, 1862, in “Providence has been kind,” Military Images (January–February 1999): 22–23; James P. Stewart to Mother, CWTI Collection, Army Heritage and Education Center (AHEAC); Thomas F. Galwey, The Valiant Hours (Harrisburg, 1961), 42.

2. Galwey, The Valiant Hours, 38; Ben Milikin to John M. Gould, March 1, 1895, Gould Papers (GP), Dartmouth College: Blake McKelvey, ed., The Civil War Letters of Francis Edwin Pierce of the 108th New York Volunteer Infantry (Rochester, 1944), 152; Frederick L. Hitchcock, War From the Inside (Philadelphia, 1904), 56.

3. “Letter from a Mobile Rifleman,” Mobile Advertiser and Register, October 18, 1862; Ambrose [or Ambrus] Rufus Collins to “wyfe and children,” September 8, 1862, Antietam National Battlefield Library (ANBL); Robert W. Withers to Ezra Carman, March 14, 1895, ANBL.

4. Rufus Dawes, Service With the Sixth Wisconsin Infantry (Dayton, OH, 1984), 87; Memphis Daily Appeal, October 11, 1862.

5. Samuel H. Walkup journal, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC).

6. Ezra A. Carman, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, ed. by Thomas G. Clemens (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2012), 56–57; Dawes, Service With the Sixth Wisconsin, 88.

7. George L. Beal report, U.S. Army Generals’ Reports of Civil War Service, vol. 10, 561, RG 94, National Archives (NA); James Fillebrown to wife, September 19, 1862, Lewiston (ME) Falls Journal, October 2, 1862; Peter Noll, September 17, 1862, letter in Reading (PA) Daily Times, September 25, 1862; James Lane to Ezra Carman, March 22, 1895, Antietam Studies Collection (AS), NA.

8. Milo M. Quaife, ed., From the Cannon’s Mouth: General Alpheus S. Williams (Lincoln, NE, 1995), 125.

9. Dawes, Service With the Sixth Wisconsin, 90.

10. Edmund R. Brown, The Twenty-Seventh Indiana Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion, 1861 to 1865: First Division, 12th and 20th Corps (Monticello, IN, 1899), 249.

11. William Houghton to Mother, September 21, 1862, Indiana Historical Society; B.B. Ross reminiscences, USAHEC.

12. Frank Holsinger, “How It Feels to Be Under Fire,” in Henry Steele Commager, ed., The Blue and the Gray (Indianapolis, 1973), vol. 1, 316.

13. B.B. Ross Reminiscences, USAHEC; Holsinger, “How It Feels to Be Under Fire,” 315; Holsinger to John Gould, February 29, 1893, GP.

14. R.T. Coles, From Huntsville to Appomattox, ed. Jeffery D. Stocker (Knoxville, 1996), 67; Joseph Frame Consolidated Service Record, RG 109, NA; Samuel Moore diary, ANBL; Wm. Halstead to Gould, March 3, 1893, and Wm. P. Gifford to Gould, Mar. 7, 1893, GP.

15. Samuel Hodgman to Father, November 17, 1862, U.S. Civil War Collection, Western Michigan University.

16. Edward W. Spangler, My Little War Experience (York, PA, 1904), 30–31.

17. H. Waters Berryman to Mother, September 22, 1862, 1st TX file, ANBL; Henry Ropes to John, September 20, 1862, Henry Ropes letters, Boston Public Library; William E. MacDonald, “The Long Roll Diary of a Yankee Mudsill,” ed. Robert E. Elsden, 2nd MA file, ANBL; Austin Carr diary, USAHEC.

18. Seth Plumb to Friends, September 20, 1862, Plumb Family Papers, Litchfield Historical Society, CT.

19. John Whiteside to Mother, October 4, 1862, Michigan Historical Collections, Bentley Library, University of Michigan.