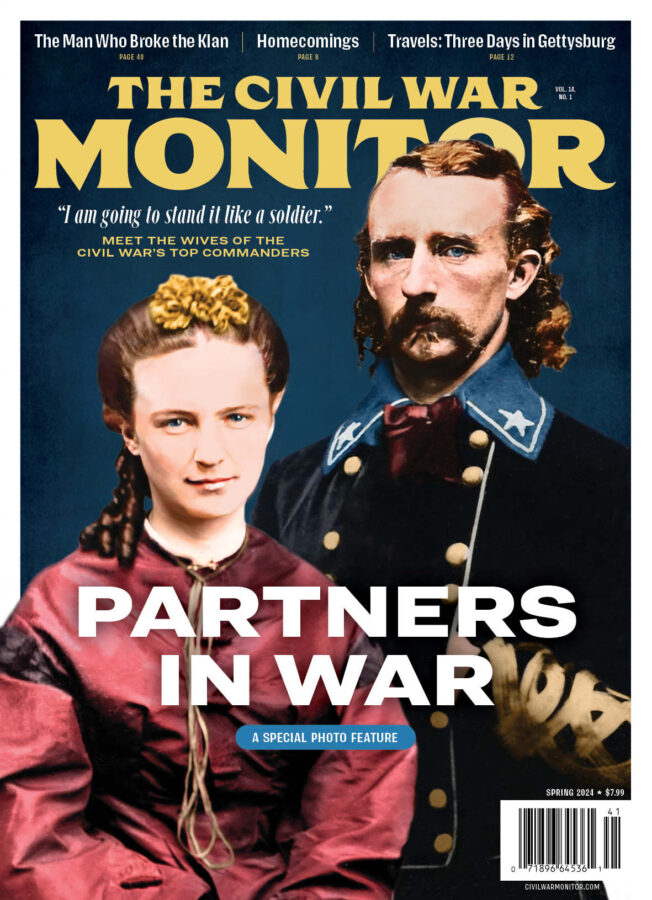

Partners in War

Thanks for another great issue! I loved the feature in which you profiled the wives of Civil War generals [“Partners in War,” Vol. 14, No. 1]. I hadn’t seen photos of many of these women before, and the stories that accompanied them were interesting—some heartbreaking. I’d love to see more photo-based articles like this in future issues.

Please keep up the good work!

Pat Freeman

Via email

* * *

I just received the latest issue [Vol. 14, No. 1] of The Civil War Monitor and was drawn right away to the “Partners in War” feature. The women are brought to life in pictures and in their own words as I have never seen before. It is interesting to have this view into the women who stood behind the generals.

This issue is more evidence of your great work in bringing to life important aspects of the war that haven’t been well covered.

Alan F. Sewell

Via email

* * *

The interesting article on generals’ wives was ruined by use of colorized photos. For example, Mrs. Halleck is shown in a purple dress. For all we know, she detested the color purple. Colorization thus disserves both the person portrayed and modern readers, who have a right to expect accurate history from a history magazine.

John Braden

Fremont, Michigan

* * *

I enjoyed the photo article on the wives of prominent Civil War generals. Maybe in a future issue you could focus on the wives of lower-ranked commanders? That might be interesting too.

Rich Bennett

Via email

Ed. Thanks to all for your feedback. We very much enjoyed putting that article together—though, due to space constraints, we faced a few difficult decisions about which wives made the final list, and which just missed. As to John’s displeasure at the colorizations: While it’s true that there isn’t, and perhaps never will be, certainty about the accuracy of all the hues assigned to every aspect of historical photos subjected to colorization, we believe the benefits of the final results outweigh the drawbacks. Colorization—a practice that’s been around since the 19th century, virtually as long as photography itself—can lend a powerful vibrancy to the original images that, at its best, helps bring them to life, making their subjects more relatable, meaningful, and relevant to us. In short, we view the process as a responsible—and rather harmless—way to enhance certain historical images, rather than a disregarding or falsifying of history.

A Visit to Gettysburg

Your travel article on Gettysburg [“Travels: Three Days in Gettysburg,” Vol. 14, No. 1] left out one attraction I hope is still operating: the horseback tours of part of the battlefield.

When I was there a few years ago, I found the rides gave a totally different perspective. On the ground covered by Pickett’s Charge, the view from either Emmitsburg or Taneytown roads does not give a good feel of the undulations of the ground. And when the guide tells you, “The right flank of the charge was right about here, and the left flank formed at those trees and roof line you see far to your left,” you get a good understanding of how many men were involved and the obstacles they faced.

Similarly, it’s one thing to read that Major General Daniel Sickles took his men out in advance of his assigned position on the battle’s second day, but sitting on a horse at the spot where he was wounded lets you understand exactly how outrageous his move was.

Kathleen Dawson

Englewood, Ohio

Ed. Thanks for your note, Kathleen. A Google search turns up several companies that offer horseback tours of Gettysburg. Folks interested in signing up for one would be wise to investigate ahead of their visit to learn about the available options.

Observatory

I read the “Observatory” column in your latest issue [“The Centennial & The Twilight Zone,” Vol. 14, No. 1] about episodes of The Twilight Zone that focused on the Civil War during the Centennial, and I wanted to draw your attention to another show that aired an impressive, for that time, story about the war. Season 2, Episode 1 of The Rebel, which aired in September 1960, is titled “Johnny Yuma at Appomattox.” I spotted it in on a cable channel three years ago and decided to see how it portrayed the Confederate surrender and was very pleasantly surprised.

The fictional framework of the episode depicts Yuma, sometime after the war, telling a boy what he had seen and heard at Appomattox. Yuma was a Confederate soldier who, after learning that Robert E. Lee’s surrender was imminent, snuck into the Wilmer McLean House from the back to kill Ulysses S. Grant as the two generals met in the parlor. Having found a spot in the attic where he could observe events without being discovered, Yuma waited for Grant to show up. Lee arrived first and, soon after, Grant. Since Yuma’s aim was obstructed, he ended up seeing and hearing everything that took place during the generals’ meeting and, surprisingly, the details were historically accurate, the dialogue between Grant and Lee matching their actual words, as they’ve been reported, almost verbatim. Yuma, deeply affected by their exchange, decides not to fire.

This episode includes other little things, historically accurate, that have no direct bearing on the story being told. For instance, a Confederate officer mentions in conversation the names of Confederate generals who have been killed, and they were not fictionalized names. (I can’t recall all the names three years later, but Major General Robert Rodes was one of them. Outside of historians, who in 1960 would recall Rodes?) Another scene has Grant mentioning that he had a splitting headache that day that dissipated after he received the dispatch from Lee in which he agreed to surrender, something that Grant mentions in his memoirs. Details like this would have gone unnoticed by likely 99% of the episode’s audience, so someone cared enough about history to put those small things in anyway. I was surprised that they went to that much trouble but it made the program that much more enjoyable. To date, this is the best interpretation of the surrender I have seen in media. Watch it yourself and be amazed.

Richard Wilkinson

Via email

About Those Flags

I had just finished reading the article “The Centennial & The Twilight Zone” [“Observatory,” Vol. 14, No. 1] and had my TV on when, lo and behold, The Twilight Zone appeared and of course the episode was “The Passerby.” I had seen all of the mentioned Civil War-related episodes before, but I paid special attention. Very chilling story and James Gregory, with his strong voice, played his part as “the Sergeant” well. Frightening music and wonderful story by Rod Serling. Thank you for the article.

I also found fascinating “The Broken Glass Plate of Lincoln and McClellan” [“In Focus,” Vol. 14, No. 1]. I have seen this photograph tens and tens of times over the years but had never seen the Confederate battle flag lying on the grass just feet away from President Lincoln as he sits across from George McClellan. Is there a further story about the flag, or do we assume it is a captured item? Most times this photo is cropped so I had never seen this before.Keep up the good work.

Anthony Brixius

Hot Springs, South Dakota

* * *

Your Spring 2024 issue shows the “Broken Glass Plate” in which Lincoln appears to be sitting next to an American flag that is being used as a tablecloth. In addition, a wrinkled flag is lying on the ground. One would expect these two leaders would show more respect to the American flag.

Ron Jacobs

Pleasantville, Pennsylvania

Ed. Thanks, Anthony and Ron, for your feedback. The image does show an American flag draped over the table next to Lincoln and a Confederate battle flag on the ground close by. We asked the Center for Civil War Photography’s Bob Zeller if he could shed further light on the banners. He writes: “Mr. Jacobs’ comment about the American flag being used inappropriately in that scene is a matter of conjecture. It’s obviously covering a table and something is sitting on top of it, but it could have been put there more or less as a display. The person who made the image, Alexander Gardner, was known to add props to his photos, such as muskets, etc. The Confederate flag on the ground quite possibly was added to enhance the photo. Gardner shot both a stereo negative and a large plate negative of this scene. I know of no documentation or writings about the flag, but have always assumed that it is a captured Confederate battle flag. In his book on Antietam photography, Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day (1978), Bill Frassanito says it’s one of 39 Confederate flags Union forces captured during the Maryland Campaign.”

The Draper Raid

I really enjoyed the article “The Draper Raid of 1864” in your Spring 2024 issue. Alonzo Draper had a bit of David Hunter in him. The evidence that there were terrible crimes committed by the men of the 36th USCT seems to be trustworthy. The fact that it was generally accepted so quickly that terror had occurred—and that news of it reached as high up as Robert E. Lee himself—makes me think it’s a good guess that news of ravages committed by Draper’s black troops were more than racist rumors. But even so, Draper probably didn’t order a mass depredation spree during the raid; he just didn’t do anything about it, which is just as bad.

Pete Hale

Via email

Submit your letters to the editor. Email us at [email protected] or write to The Civil War Monitor, P.O. Box 3041, Margate, NJ 08402