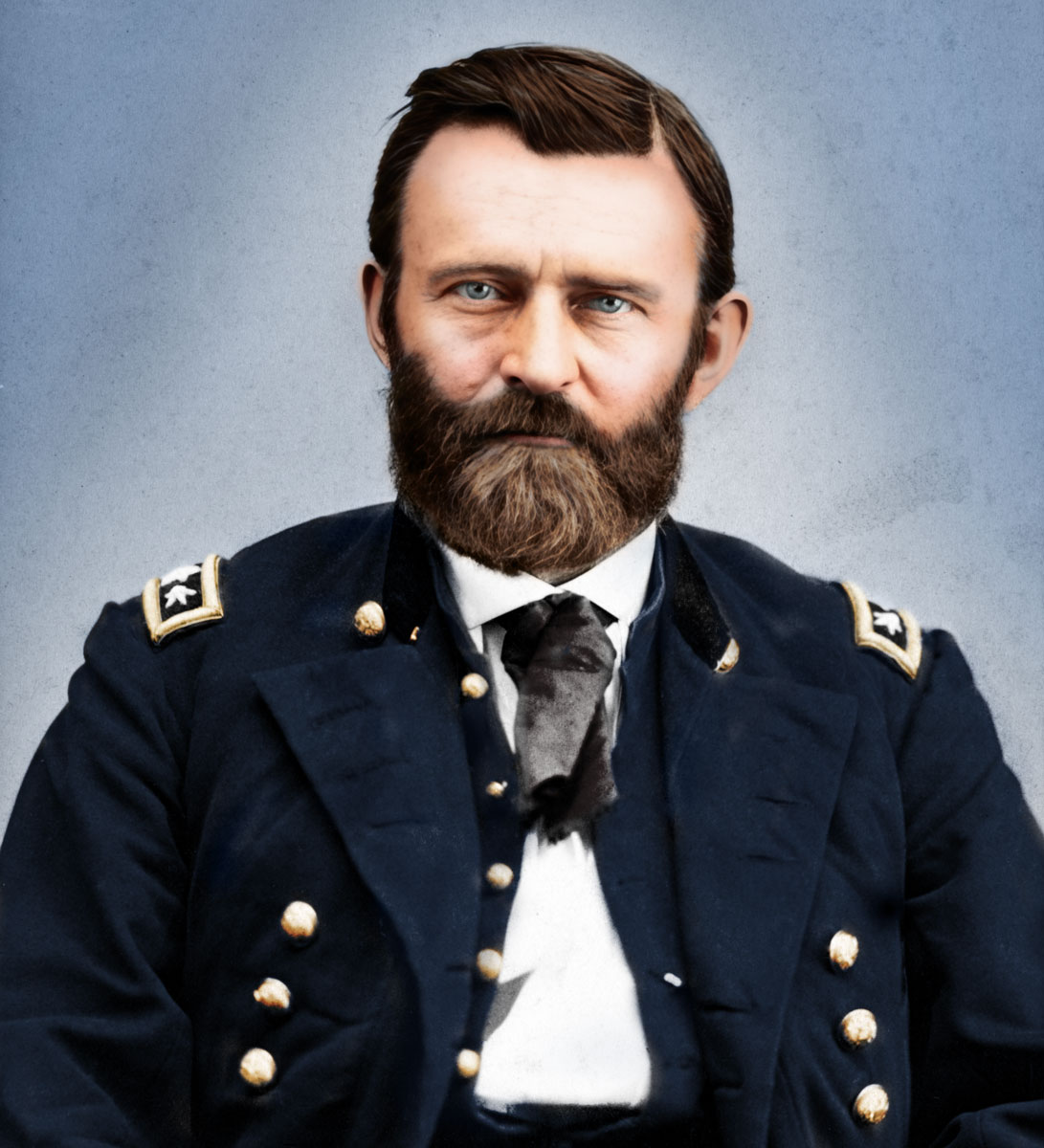

Library of Congress, colorized by Patrick and Dylan Brennan

Library of Congress, colorized by Patrick and Dylan BrennanBefore he became the Union’s top soldier, Mexican War veteran turned store clerk Ulysses S. Grant needed to find a way back into the Army

In the spring of 1860, Ulysses S. Grant, an army veteran having suffered a variety of failures for years in the civilian world, relocated his family to Galena, Illinois, where his father, Jesse R. Grant, owned a leather goods store. The son, 38, had accepted his father’s offer to work as a clerk in the shop. Supposedly, his father said: “Now, Ulysses, you’ve made a failure of life so far as you’ve gone; I hope you’ll do better in the store than you have elsewhere. I am afraid West Point didn’t do you any good. You must get down to business now.”1

The shop, which resembled a general store and sold merchandise other than just leather goods, was located on Main Street on the ground floor of a three-storied brick building with a wooden sidewalk outside. That spring, Augustus Chetlain, a wealthy merchant, met Grant for the first time. Chetlain recalled that Grant “was really more than an ordinary clerk, for he at times was a salesman, and at other times a collector, going out to country towns, and occasionally doing the work of a bookkeeper.” Most people in the town recognized Ulysses by sight, but few knew his name. He was a pleasant fellow, always free with a wave or a nod as he passed, but no one knew him well except for his wife, Julia, and their four children, his brothers, Orvil and Simpson, and the clerks who worked with him. Although most people regarded Grant as a quiet man who shied away from conversation, Chetlain got to know the former army captain as “a free and interesting talker” who “frequently entertained his friends and neighbors by the hour in relating his experiences in the Mexican war and while stationed a few years on the Pacific coast.”2

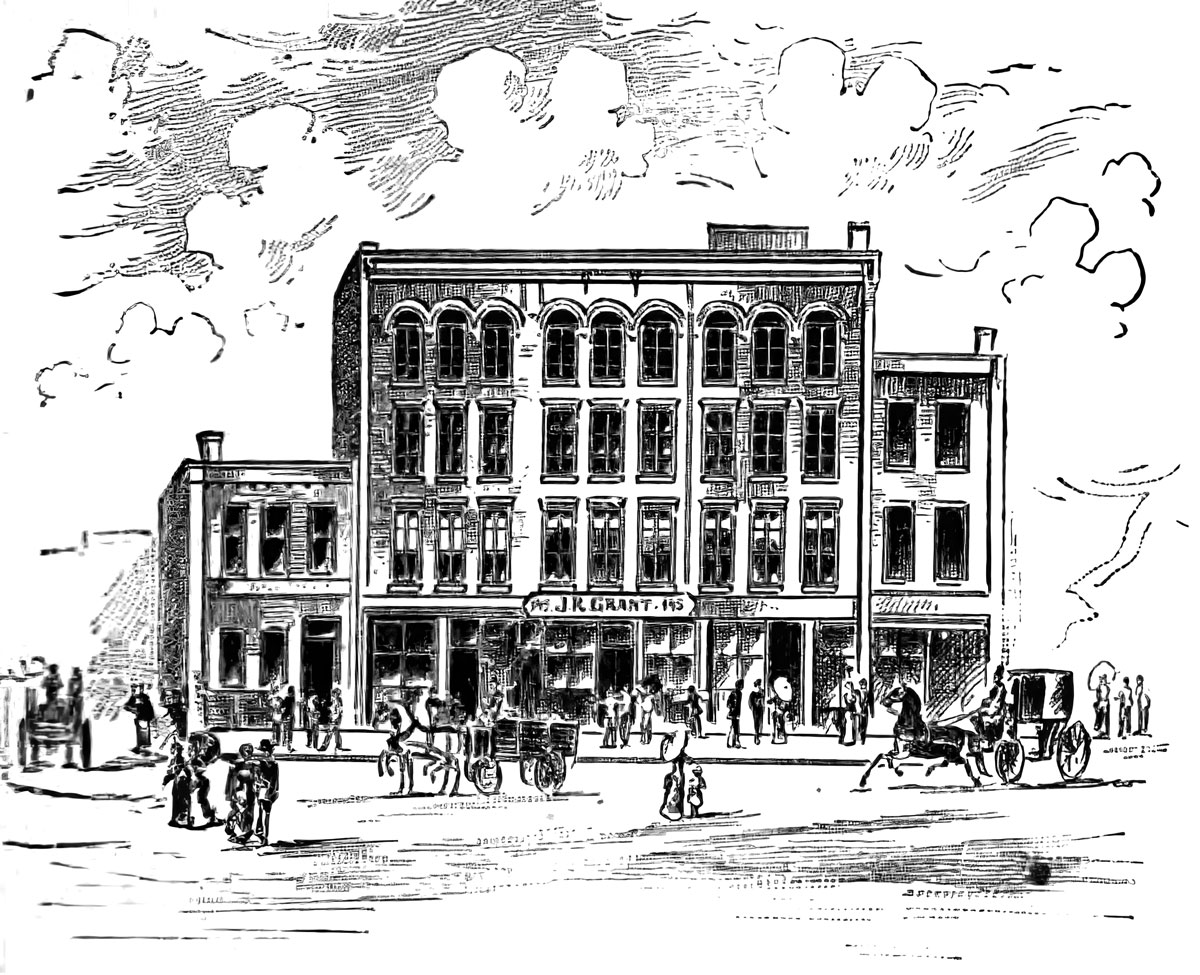

"A New, Original and Authentic Record of the Life and Deeds of General U.S. Grant" (1885)

"A New, Original and Authentic Record of the Life and Deeds of General U.S. Grant" (1885)After relocating his family to Galena, Illinois, in the spring of 1860, Ulysses S. Grant—an army veteran who had suffered a variety of failures in the civilian world—went to work at his father’s leather goods store (pictured above in a postwar illustration). “You must get down to business now,” his father reportedly told his 38-year-old eldest son at the time.

Every morning, dressed in his old coat of army blue, a black slouch hat, and high leather boots, Grant walked down the steep wooden steps (more than 200 of them) that connected the terraces of the high ridge, where he rented a house, with Main Street and the levees below on the Galena River. He liked Galena and was seen regularly walking the city smoking his clay pipe—but he did not like clerking, even with his father and brothers. The job did not relieve Grant’s post-army financial woes, although he hoped eventually to become his brothers’ partner, but Simpson suffered from consumption and could not entirely hold his own in the business, which put pressure on Grant to learn the trade quickly.4

A fellow clerk, Melancthon T. Burke, later remembered how conscientiously Grant would work to get the job done: “Grant was of great physical strength and I have seen him many times lift a hide that no ordinary man could manage. After tossing and weighing the hides, he would calmly walk over and wash his hands. Then he would resume his common position of reclining in a chair, feet on the counter. He was very relaxed in his habits and stance.”5 Unfortunately, he learned slowly and had little enthusiasm for buying and selling leather.

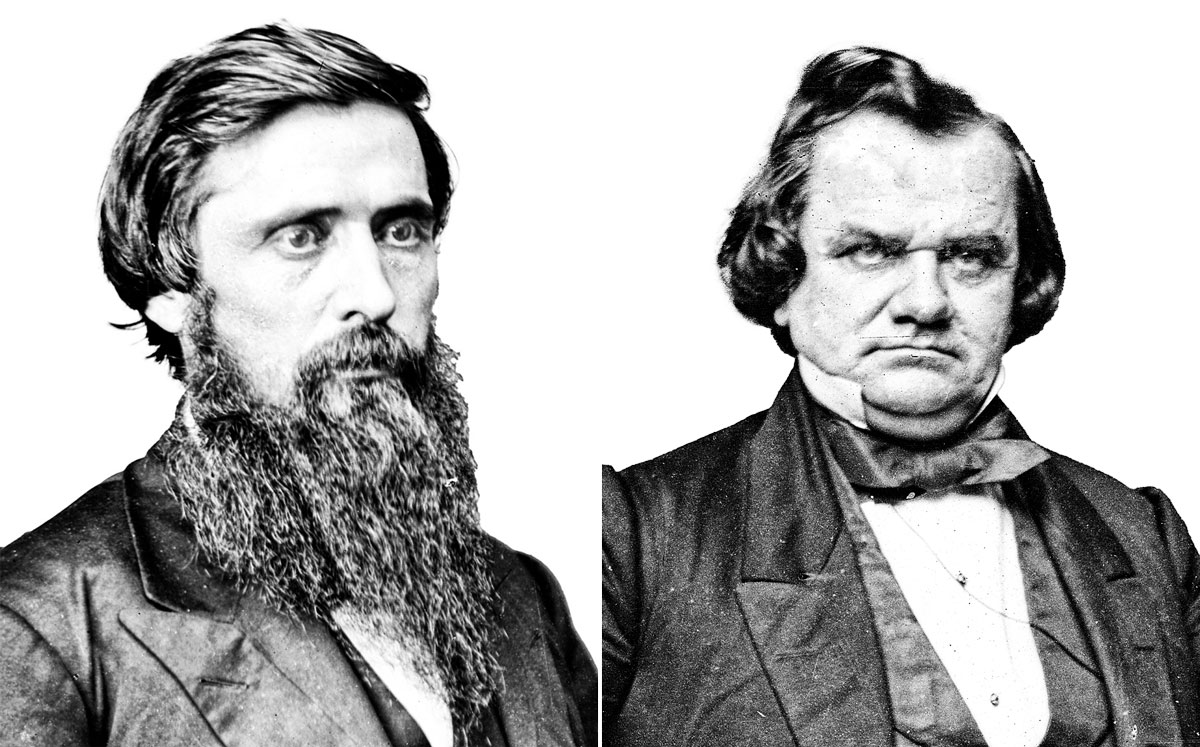

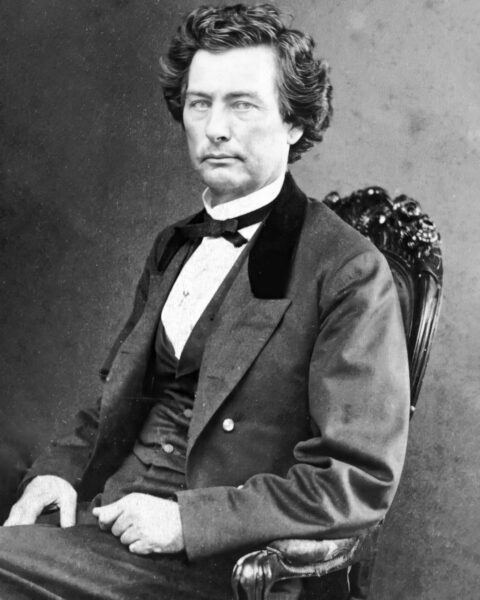

Library of Congress (Rawlins); National Portrait Gallery (Douglas)

Library of Congress (Rawlins); National Portrait Gallery (Douglas)John A. Rawlins (left) and Stephen A. Douglas

One of Grant’s good friends was John A. Rawlins, a Galena native who wore a long, messy beard and had dark penetrating eyes. Despite having little schooling, Rawlins had educated himself and was an attorney. He lived in the shadow of his father, James, who frequently imbibed. Striving to be unlike his father, Rawlins swore off liquor, considering inebriation a sign of dissipation. He was regarded as a competent lawyer, a gifted orator, and an intelligent man who could be blunt and cold. Like Grant, he was a Democrat and paid his political allegiance to Stephen A. Douglas, the “Little Giant” who had beaten Abraham Lincoln in the 1858 Illinois senatorial election but who would lose to Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election. With the outbreak of war, Rawlins, like Grant, believed that partisan politics should play no part in how the North and West responded to southern secessionists.3

The election of 1860 electrified Galena, a town divided, like the nation, between supporters of free labor and slave labor. Senator Douglas gave a campaign speech there, but Grant disliked what he said, and leaned more toward Republican politics, perhaps influenced by his Republican father and brothers and the intense political discussions in the store. He couldn’t vote in the November election because he hadn’t resided long enough in Illinois to meet the suffrage requirements, but that didn’t mean he lacked interest.

Rumors spoke of war after Lincoln won the presidency. When word of Fort Sumter’s fall reached Galena on April 16, 1861, the residents closed their businesses, a parade erupted with marching bands playing patriotic and military tunes, and rural folk from miles away flooded into the town to learn what the tumult was all about. Inside the store, where customers and friends gathered that afternoon, Grant no longer conversed casually about his old soldier days. “I thought I had done with soldiering,” Grant said to the people in the shop. “But I was educated by the Government; and if my knowledge and experience can be of any service, I think I ought to offer them.”6 And army pay would help solve his financial troubles.

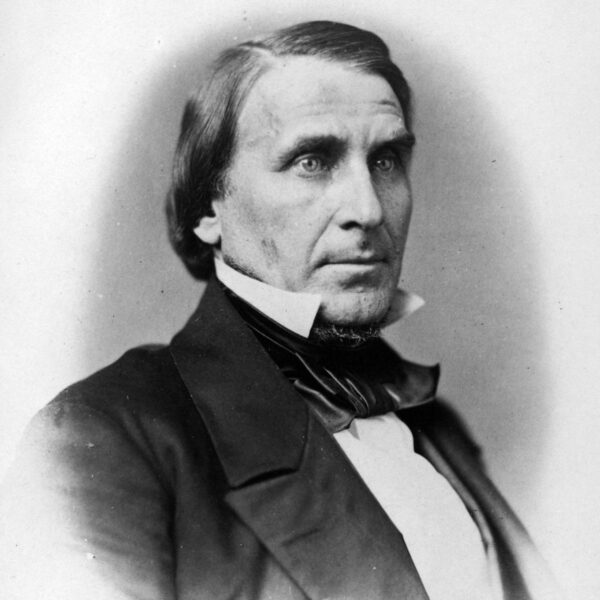

Library of Congress

Library of CongressShortly after the Fall of Fort Sumter, U.S. Representative Elihu B. Washburne arrived in Galena from Washington, D.C., and held a rousing Union meeting that Grant attended. He reportedly told his brother afterward, “I think I ought to go into the service.”

U.S. Representative Elihu B. Washburne arrived from Washington, where he had served in Congress since 1852, and announced a Union meeting that evening. Patriotism was being galvanized. A crowd, marching as if in a military column, filled the courthouse and almost immediately reacted in opposition to the mayor’s recommendations for the nation to seek compromise and peace. After the uproar died down, the discussion focused on raising troops to put down the rebellion. The call went up to assemble two companies from Galena. Washburne admonished the audience that “any man who will try to stir party prejudices at such a time as this is a traitor!” After delivering a rousing speech, the congressman recommended “the immediate formation of two military companies … to respond to any call that may be made by the governor of the state.” Having lived “under the stars and stripes by the blessing of God,” he told his constituents, “we propose to die under them.” The audience voted to organize the military companies at once.7

The night was still young. Enthusiastic and patriotic speeches were delivered by Rawlins and Charles S. Hempstead, Washburne’s venerable law partner, and by others, all of whom spoke of duty to the Union in the face of southern treason. Rawlins was vociferous, stating, “I have been a Democrat all my life, but this is no longer a question of politics. It is simply country or no country…. Only one course is left for us. We will stand by the flag of our country, and appeal to the God of Battles!” A tremendous cheer shook the hall, and Democrats and Republicans alike yelled in concert for Rawlins, who had set his cap with the Union cause. Grant and his brother Orvil had stood in the audience and walked home after the meeting. “I think I ought to go into the service,” Grant said. “I think so too,” Orvil replied. “Go, if you like, and I will stay at home and attend to the store.”8

Two days later, a second meeting took place with yet another huge crowd filling the courthouse to capacity. Washburne, Chetlain, and others conspired to name the former Captain Grant as the meeting’s chairman. Grant was taken aback, for such a public role was something he did not seek, and his innate shyness and preference against speaking to an audience made him hesitate about ascending the platform. From the rear of the hall, he pushed through the crowd, and from a desk on the floor, said: “Before calling upon you to become volunteers, I wish to state just what will be required of you. First of all, unquestioning obedience to your superior officers…. Many of the orders of your superiors will seem to you unjust, and yet they must be borne.” Army life would be strenuous and demanding. In conclusion, he said, “so far as I can I will aid the company, and I intend to reenlist in the service myself.”9

Against Grant’s somber comments, the crowd’s boisterous enthusiasm subsided. Individuals asked pragmatic questions and Grant answered every one. With that, he stepped aside, and Washburne again got to stir up the assembly’s patriotic zeal and desire to enter the ranks of Galena’s new militia. Some assumed that Grant would become captain of the company, the Jo Daviess Guards, but he declined. “I can’t afford to reenter service as a captain of volunteers,” he told friends. “I have served nine years in the regular army, and I am fitted to command a regiment.” To Chetlain, Grant explained that, as a West Point graduate, “I have been a Captain in the regular army and I should have a Colonelcy or a proper staff appointment—nothing else would be proper.”10

Washburne showed some concern over Grant’s decision not to command the local militia company, and asked for his reasons. “I left the army, expecting never to return,” Grant explained. “I am no seeker for position, but the country, which educated me, is in sore peril, and, as a man of honor, I feel bound to offer my services for whatever they are worth.” Grant believed his services were worth as least a colonelcy. Washburne understood. “Captain,” he said, “we need just such men as you—men with military education and experience. The Legislature meets next Tuesday [April 23]; several of us are going to Springfield; come along—you will surely be wanted.”11 Grant wanted to defend the Union. But he also wanted an officer’s prestige.

Despite Washburne’s encouraging remarks, Grant seems not to have fully understood that he had a powerful politician on his side. Washburne came from a family descended from the Pilgrims and devoted to public service. Unlike the rest of the family, including his parents and eight siblings, Washburne added the letter “e” to the surname to align it with English spellings. As a young man, he had worked as a printer’s apprentice, a schoolteacher, and a law apprentice, and then entered and graduated from Harvard Law School. Taking the advice of a younger brother, Washburne relocated to Galena, where neighboring lead mines had turned it into a boom town. He joined the Whig Party and met Lincoln when they both served as attorneys before the Illinois State Supreme Court. From 1855 to 1861, he served in Congress shoulder-to-shoulder with his two brothers, Israel and Cadwallader Washburn, each of them representing a different state. In the mid-1850s, Washburne helped organize the Republican Party in Illinois, and he strongly supported Lincoln’s burgeoning political career.12

As the committee chairman on both Commerce and Appropriations, Washburne wielded formidable power in the House of Representatives. He also looked every part the handsome congressman. Despite his charm, he made enemies in the halls of government. Gideon Welles, secretary of the navy under Lincoln, called Washburne “the meanest man in the house.”13 But he felt only fondness for Grant. Over time, the two men realized they needed each other. Washburne supported and protected Grant from critics in Washington. Grant, in turn, delivered victories not only to the Union, but also to his vigorous political sponsor. Both men gained in reputation and luster. Grant knew when to share information with his congressman and when to keep him in the dark. Over the years, Grant played Washburne as effectively as Washburne played him.14

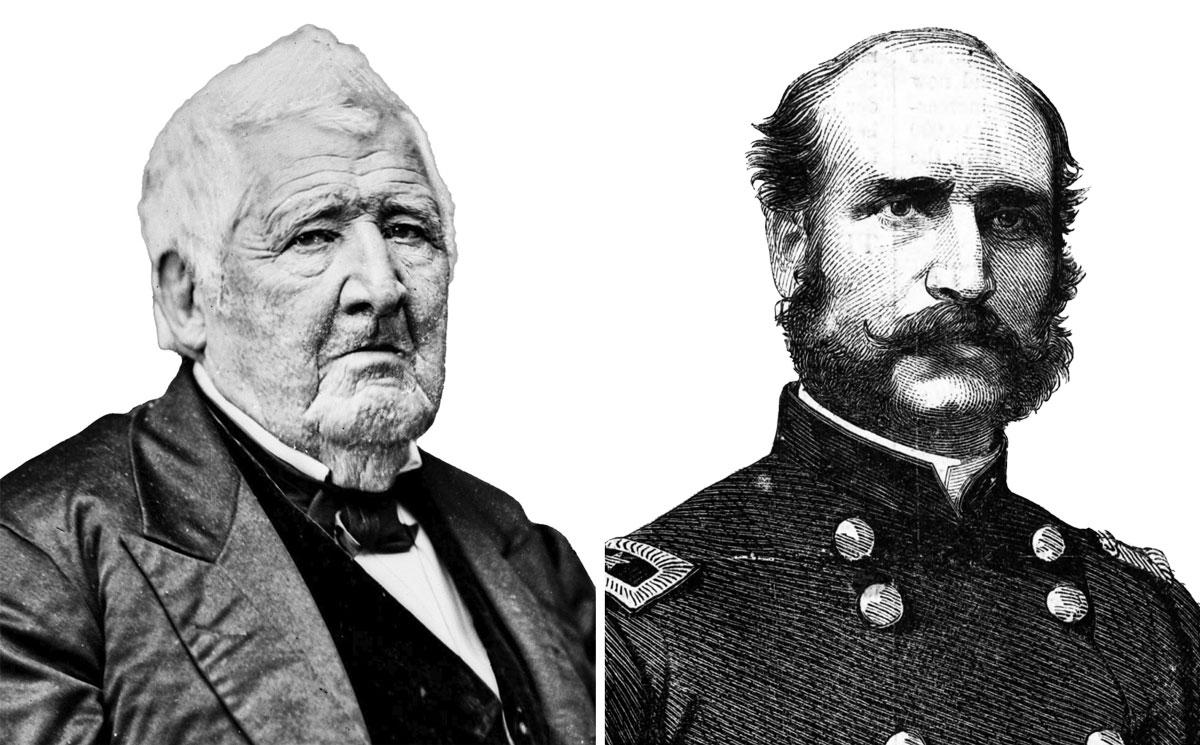

Library of Congress (Dent), "Harper's Weekly" (Chetlain)

Library of Congress (Dent), "Harper's Weekly" (Chetlain)Frederick Dent (left) and Augustus Chetlain

On the day after the second war meeting in Galena, Grant wrote to his father-in-law, Frederick Dent, and insisted that the time had come for loyal men in the border states, including Dent’s state of Missouri, “to prove their love of country.” Every true patriot must stand up, be counted, and work for “maintaining the integrity of the glorious old Stars & Stripes, the Constitution and the Union.” He also criticized Dent’s southern sympathies: “No impartial man can conceal from himself the fact that in all these troubles the South have been the aggressors and the Administration has stood purely on the defensive, more on the defensive than she would dared to have done but for her consciousness of strength and the certainty of right prevailing in the end.” Grant also predicted that the coming war meant “the doom of Slavery.” Showing his understanding of global economics, he pointed out that the conflict would “give such an impetus to the production of their staple, cotton, in other parts of the world that they can never recover the controll of the market again for that comodity. This will reduce the value of negroes so much that they will never be worth fighting over again.”15

On April 21, Grant, in a letter to his father, repeated his sense of duty to the Union government that had educated him “for such an emergency” and, he wrote, had claims on him “that no ordinary motives of self-interest can surmount.” Rather than enlisting, however, he spent his time helping to organize and train the Jo Daviess Guards by giving it and its elected captain, Augustus Chetlain, whatever advice he could on military matters. His activity included drilling the recruits and informing a tailor as to the design of uniforms for the company. Grant also expounded on his political beliefs: “We have a Government, and laws and a flag and they must all be sustained. There are but two parties now. Traitors & Patriots and I want hereafter to be ranked with the latter, and I trust, the stronger party.” He required something from his father, however. “What I ask now is your approval of the course I am taking, or advice in the matter,” he wrote.16 It comes as something of a surprise that Grant, just days shy of turning 40, sought the approval of his father, with whom he had had a contentious relationship over the years. Most likely, he wanted to know if his father would free him from the leather shop. Yet the letters to his father and father-in-law suggest that Grant still had not become his own man. He wanted to know from his elders if he was doing the right thing.

On April 25, Grant and the Jo Daviess Guards began their journey to the capital, Springfield, where all the Illinois recruits gathered to be mustered into regiments. Thousands of people, cheering and crying, gathered in Galena to watch as the company headed to the train depot. On its way, the train passed crowds at every railway stop en route. “There is such a feeling arroused through the country now as has not been known since the Revolution,” Grant wrote to his wife. “Evry company called for in the Presidents proclimation has been organized, and filled to near double the amount that can be recieved.” Governor Richard Yates accepted the Galena company into state service under Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops.17

Library of Congress

Library of CongressOn his quest for a colonel’s commission, a scraggly Grant visited—and made a poor impression on—Illinois Governor Richard Yates (shown here in a wartime image), who suggested Grant instead seek the state adjutant general’s help.

Grant, still hopeful of obtaining a commission, carried with him a letter of introduction from Washburne. He briefly met with the governor—and made a particularly poor impression. He looked like a country bumpkin, dressed in his only suit, which he had worn all winter, a short pipe protruding from his lips, his beard grizzled, and—according to his father—“his old slouch hat did not make him look a very promising candidate for the colonelcy.” Yates read Washburne’s letter and told Grant that he had already granted all available commissions. The governor suggested that he seek out the state’s adjutant general, which Grant did, learning that he could only be employed as a clerk. He needed the work and the money, so he accepted the clerkship at $2 a day and soon found himself laboring in a tiny office adjacent to the governor’s suite in the state capitol, filling out papers on a three-legged table, which, according to Chetlain, “had been shoved into a corner to keep it upright.” When Chetlain visited him a few days later, Grant, dressed in civilian clothes, sat at the table with his hat on, smoking his pipe. As Chetlain remembered the moment, Grant looked up at him “with an expression of weariness and disgust on his face,” and said: “I am copying orders and I am going to quit and go home. Any enlisted man could do this as well as I, or better.”18

Chetlain and Washburne convinced Grant to stay on a bit longer in Springfield to see what might come up. Yates told Washburne that the former army captain might be useful mustering men into the state’s regiments. During this time, Grant spread his Unionist ideas to anyone who would listen, including his sister Mary. Underestimating southern devotion to slavery and secession, and overestimating Unionist fidelity in the North, Grant told Mary he believed “that if the South knew the entire unanimity of the North for the Union and maintenance of Law, and how freely men and money are offered to the cause, they would lay down their arms at once in humble submission.” A few days later he did admit to his father that he presumed war fever was “just as strong on the other side, but they are infinitely in the minority in resources.”19

By early May, Yates gave Grant the task of mustering in the raw regiments as they arrived at Camp Yates, which was just outside Springfield. Grant was not happy with this role either; he explained away his failure to secure a colonelcy because those commissions went to men who had pulled political strings to get their places (even while Washburne and his Galena friends continued their efforts to get Grant a colonel’s slot). “All is buzz and excitement here, as well as confusion,” he informed his wife, “and I dont see really that I am doing any good. But when I speak of going it is objected to by not only Governer Yates, but others…. I imagine it will do me no harm the time I spend here, for it has enabled me to become acquainted with the principle men in the state.” His pay had been increased to $140 a month. Like most of the family men swept into the war, Grant missed his wife and children.20

Despite the turbulence of the times, and his own desire to get into the conflict, Grant doubted if the war would last very long. He also believed that the Union would easily defeat the states in rebellion. But his military acumen did not work on his assumptions that so closely resembled northern public opinion. To Julia, he wrote: “As people from the Southern states are allowed to travel freely through all parts of the North and cannot fail to see the entire unanimity of the people to support the Government, and see their strength in men and means, they must become soon dishartened and lay down their arms. My own opinion is there will be much less bloodshed than is generally anticipated.” Grant also misjudged the role of enslaved blacks as the war geared up. Predicting a Union victory, he asserted that “all the states will then be loyal for a generation to come, negroes will depreciate so rapidly in value that no body will want to own them and their masters will be the loudest in their declaimations against the institution in a political and economic view. The nigger will never disturb this country again. The worst that is to be apprehended from him is now; he may revolt and cause more destruction than any Northern man, except it be the ultra abolitionest, wants to see. A Northern army may be required in the next ninety days to go south to suppress a negro insurrection.”21

Despite the turbulence of the times, and his own desire to get into the conflict, Grant doubted if the war would last very long.

He was wrong on every count. Grant feared a slave rebellion—and assumed it would surely happen if the Union won the war—more than he feared the militancy of the white South. “The worst to be apprehended,” he warned his wife, “is from negro revolts. Such would be deeply deplorable and I have no doubt but a Northern army would hasten South to suppress anything of the kind.” He did not envision that northern troops would be joined by southern troops to put down a slave rebellion. In the event of a rebellion, he thought that its suppression would only be undertaken by Union forces. Grant was revealing the racial prejudices born not of his upbringing, for his father was an antislavery Methodist, but of the influences of Julia Dent and the Dent family as Missouri slaveholders. (For a while, Grant owned an enslaved man, William Jones, but he freed him in 1859 for reasons that are not evident. He did not do so out of antislavery scruples; Julia’s slaves continued to work at Hardscrabble, the Grant farm near her father’s plantation outside of St. Louis. Grant may have emancipated Jones because he and his family could not longer afford to feed him.)22

National Portrait Gallery

National Portrait GalleryJulia Dent Grant

As May came to a close, Grant became more desperate about landing a colonelcy. Having finished his mustering service, he returned to Springfield, collected his pay, and went home to Galena. From there, he wrote to Brevet Brigadier General Lorenzo Thomas, the adjutant general of the Union army in Washington, offering his services “until the close of the War.” He told Thomas, “I would say that in view of my present age, and length of service, I feel myself competant to command a Regiment if the President, in his judgement, should see fit to entrust one to me.” Nothing came of his request. The letter, which Thomas may never have seen, appears to have been lost in the War Department until found in 1876. Grant remained in Galena for six days and then returned to Springfield, where, once more, he found no position waiting for him. To his friends, he displayed overt signs of depression. He visited Chetlain and told him: “I don’t know whether I am like other men or not, but when I have nothing to do I get blue and depressed.” He added that when that happened, he had “a natural craving for drink.” Chetlain called him “blue as a whet-stone.”23 Becoming ever more despondent, Grant fixed upon appealing to Major General George B. McClellan for a place on his staff. He obtained a week’s leave from Governor Yates and traveled to Covington, Kentucky, where he visited a while with his parents. His father joined his son’s campaign for rank and wrote letters to Attorney General Edward Bates and General-in-Chief Winfield Scott asking for his son’s commission as a colonel. There was no reply.

Grant then crossed the river to Cincinnati, where McClellan had his headquarters. Still dressed in his shoddy civilian clothes, Grant spent two days waiting outside McClellan’s office to see the general. Grant later described how he sat and watched the general’s aides working frantically. “I never saw such a busy crowd—so many men at an army head-quarters with quills behind their ears,” said Grant. “But I supposed it was all right, and was much encouraged by their industry. It was a great comfort to see the men so busy with the quills.” When McClellan did not show up, Grant returned the next day to wait some more. “I sat and waited for two hours, watching the officers with their quills, and left…. I was older, had ranked him in the army, and could not hang around his head-quarters watching the men with the quills behind their ears…. McClellan had three times as many men with quills behind their ears as I had ever found necessary at the head-quarters of a much larger command.”24

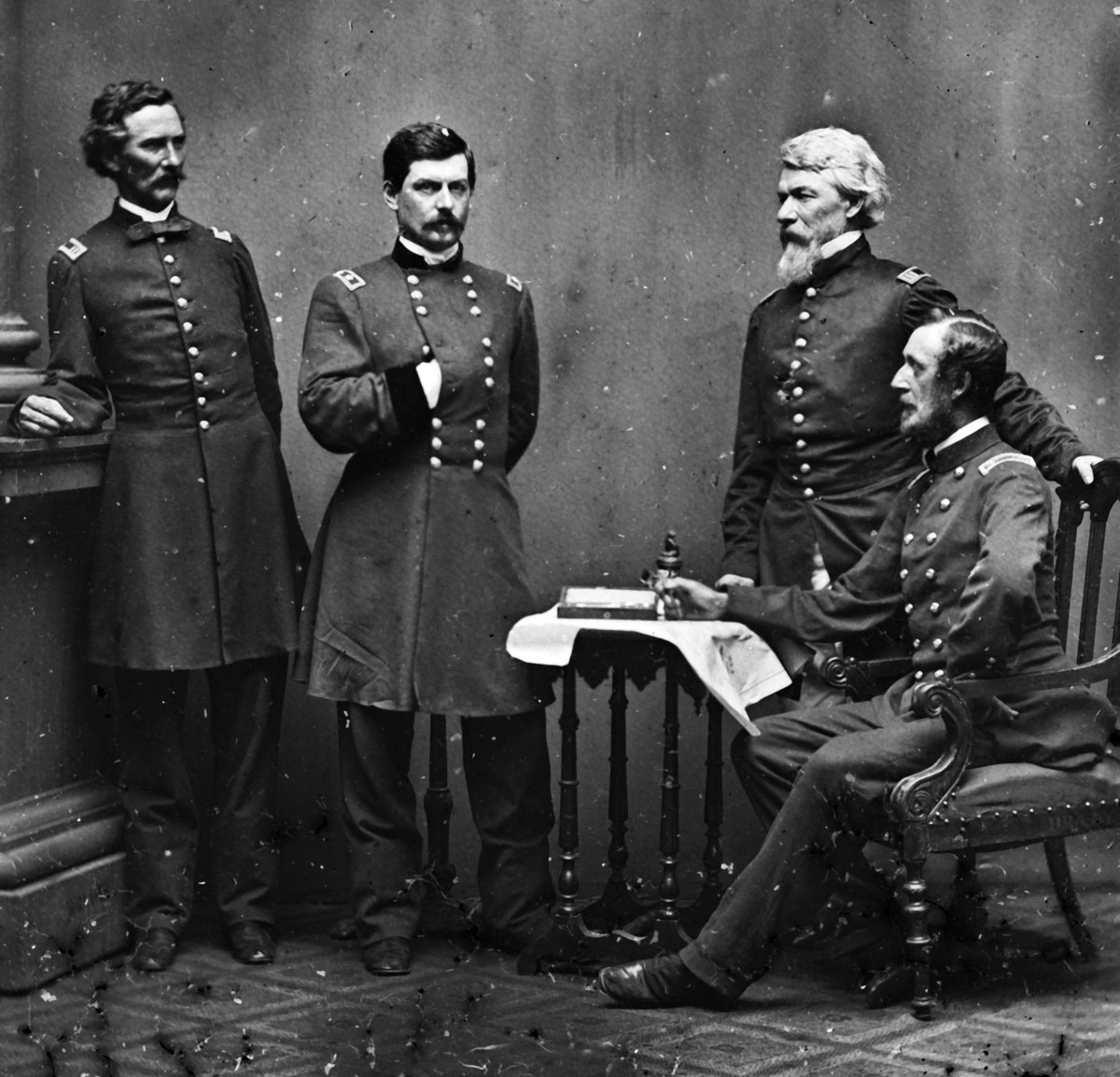

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAmong those Grant sought out in his attempt to reenter the Army as a colonel was Major General George B. McClellan (shown second from left in an 1861 photo). Grant waited two days at McClellan’s Cincinnati office, to no avail. “I never saw such a busy crowd,” Grant later wrote, “so many men at an army head-quarters with quills behind their ears.”

Then quite abruptly Yates decided to replace the colonel of the rowdy Seventh District Regiment, whose soldiers had demonstrated a willingness to flout their officers’ commands. Everywhere the governor turned, his aides and other officers suggested Grant for the job. Grant also heard rumors that Yates might appoint him to the command of an undisciplined regiment. As he waited in Springfield for developments, while also contemplating a visit back to St. Louis or to Covington, he worried that if Yates gave him a regiment, Julia and their children might not see him for quite a while. In the meantime, Yates relocated the Seventh District Regiment to Camp Yates. On June 15, McClellan arrived in Springfield and reviewed the regiment, later expressing “his satisfaction at the military proficiency of the troops there encamped.”25 His assessment defied everything known about the disorderly Seventh and its unconstrained buffoons, who would sooner play practical jokes on one another and their officers and who avoided picket duty whenever they could. That same day, Yates commissioned Grant a colonel of the Seventh, which later became the 21st Illinois Infantry.

At the camp of the 21st, Colonel Grant did not impress the soldiers. One of the governor’s aides, who accompanied Grant to the camp, described the new colonel’s arrival there: “I shall never forget the scene that occurred when his men first saw him. It was very laughable. Grant was dressed very clumsily, in citizens’ clothes—an old coat, worn out at the elbows, and badly dinged plug hat.” His men, though ragged and barefooted themselves, had formed a high estimate of what a colonel ought to be, and when Grant walked in among them they began ridiculing him. They cried out in derision, “Look at our Colonel” “What a Colonel!” “D–n such a Colonel,” and made all sorts of fun of him. Grant stood there, stoically, in his characteristic silence and glared at the soldiers. Somehow, by the power of his stare, they soon saw themselves as foolish and wanted to apologize. Grant took his anger out by making his quill fly, writing out one order after another, a ream of orders that singled out the company officers as objects of disdain, blaming them for their laxity, and spelling out rules of conduct, training, and punishments.26

Library of Congress, colorized by Patrick and Dylan Brennan

Library of Congress, colorized by Patrick and Dylan BrennanBrigadier General Ulysses S. Grant

Then the drilling began. The men drilled less often than they had under Grant’s predecessor, but now the drills were orderly, by the book, and closely monitored not only by company officers, but also by Grant himself. One of the officers recalled that Grant “insisted on the men obeying every regulation.” Everyone immediately could see that Grant knew his business, “and while he was quiet spoken, we knew he meant every word he said.” Slowly, steadily, by consistently imposing military discipline on the rank and file, Grant knocked the 21st Illinois into shape, letting his own training at West Point and his experiences in the Mexican War govern his principles of command. An enlisted man, Philip Welshimer, apprised his wife that “evry thing goes off much smoother and better since our new Colonel has got command.” In late June, a newspaper correspondent, after visiting Camp Yates, reported that there would be “no laggards” when the regiment took the field of battle against the nation’s enemies because its “good soldiers” presented “the strongest evidence of a willingness to do their duty well at all times.”27

Loyal and true, Washburne had taken the lead among several politicians from Illinois in urging Grant’s promotion to brigadier general in early August 1861. After asking for nominations of potential brigadiers, to which Washburne and the Illinois congressional delegation responded with a list including Grant’s name, Lincoln asked Secretary of War Simon Cameron to nominate Grant, among other officers, as a brigadier general. Cameron sent the nomination to Lincoln on July 31. The Senate received the nomination on August 1 and referred it to the Committee on Military Affairs, which reported to the whole chamber on August 3. On August 5, the Senate confirmed Grant’s commission.28

In the camp of the 21st Illinois, Chaplain James L. Crane read of Grant’s promotion before the general received the news. It was a hot summer’s day, Crane recalled, and he found some shade near headquarters to read a newspaper, the Daily Missouri Democrat. In the telegraphic column, he saw the announcement that Grant, along with several others, had been made brigadier general. A few minutes later, Grant walked by, and Crane called to him: “Colonel, I have some news here that will interest you.” “What have you, Chaplain?” “I see that you are made brigadier-general.” Grant sat down and reportedly remarked: “Well, sir, I had no suspicion of it. It never came from any request of mine. That’s some of Washburn’s work.”29 Grant didn’t seem much fazed by the commission. Yet this promotion, received before he had fought a single battle, must have delighted him. No more would he have to worry about gaining rank and position. He had been given the job and now would have to worry about fighting to keep it.

Grant was on his way. No mere captain, no mere colonel, he rose into higher command and the chance to prove himself to his father, his father-in-law, all the Grants and Dents, and to himself that he had overcome the stigma of failure that branded his past. From that moment on, he wanted one thing—to fight the enemy with all his might.

Glenn W. LaFantasie is the editor of the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association and the Richard Frockt Family Professor of Civil War History Emeritus at Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green.

Notes

1. Leigh Leslie, “Grant and Galena,” Midland Monthly, 4 (September 1895): 198. Jesse Grant’s remarks are probably apocryphal, although they capture the elder Grant’s typical straightforwardness and fondness for criticizing others.

2. Augustus L. Chetlain, Recollections of Seventy Years (Galena, 1899), 66.

3. “How Grant Got to Know Rawlins,” The United States Army and Navy Journal, 6 (September 12, 1868): 53. This article should have been titled “How Rawlins Got to Know Grant,” for it is an interview of Rawlins. On Rawlins, see James Harrison Wilson, The Life of John A. Rawlins (New York, 1916), which elevates Rawlins at the expense of Grant (hereafter USG), and Allen J. Ottens, General John A. Rawlins: No Ordinary Man (Bloomington, 2021), a balanced biography.

4. Samuel Simpson Grant died of consumption in St. Paul, Minnesota, on September 13, 1861. See USG to Mary Grant, September 25, 1861, in John Y. Simon et al., eds., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, 31 vols. (Carbondale, 1967-2009), 2:313 (hereafter PUSG), in which he expressed great sorrow over his brother’s death.

5. Melancthon T. Burke, Interview, n.d., Hamlin Garland Papers, University of Southern California, Los Angeles (hereafter HGP).

6. Albert D. Richardson, A Personal History of Ulysses S. Grant (Hartford, 1868), 177.

7. Richardson, A Personal History, 177-178; Chetlain, Recollections, 69–70.

8. Richardson, A Personal History, 179. On the April 16 meeting, see also “Galena,” Chicago Tribune, April 18, 1861.

9. Hamlin Garland, Ulysses S. Grant: His Life and Character (New York, 1898), 157–158.

10. Garland, Ulysses S. Grant, 159; Chetlain, Interview, ca. 1896-1897, HGP.

11. Richardson, A Personal History, 182. Many years later Washburne gave an entirely different account of his conversation with USG, which confuses the record by having USG say that he preferred to work his way up through the ranks. See Washburne, “First War Meeting at Galena, Ill.,” in W.C. King and W.P. Derby, comps., Camp-Fire Sketches and Battle-field Echoes of the Rebellion (Springfield, MA, 1889), 119. Richardson’s version is the more reliable.

12. Gaillard Hunt, Israel, Elihu, and Cadwallader Washburn: A Chapter in American Biography (New York, 1925), 155–295. There is no modern biography of Washburne, although one is sorely needed. See, instead, Russell K. Nelson, “The Early Life and Congressional Career of Elihu B. Washburne” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of North Dakota, 1953). A self-published, voluminous family memoir narrates Washburne’s life by interspersing narrative with documents. See Mark Washburne, A Biography of Elihu Benjamin Washburne, 4 vols. (Bloomington, 2000).

13. William E. Gienapp and Erica L. Gienapp, eds., The Civil War Diary of Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy (Urbana, IL, 2014), 135 (entry for February 7, 1863).

14. John Grant Wilson, ed., General Grant’s Letters to a Friend, 1861–1880 (New York, 1897); John Y. Simon, “From Galena to Appomattox: Grant and Washburne,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, 58 (Summer 1965): 165–189.

15. USG to Frederick Dent, April 19, 1861, PUSG, 2:3-4.

16. USG to Jesse Root Grant, April 21, 1861, PUSG, 2:6-7. His father replied in a letter, dated April 24, that USG mentioned in USG to Julia Dent Grant, May 1, 1861, PUSG, 2:15-16, and USG to Jesse Root Grant, May 2, 1861, PUSG, 2:17.

17. USG to Julia Dent Grant, April 27, 1861, PUSG, 2:9.

18. Hamlin Garland, Notes from a Talk by General Chetlain, n.d., HGP.

19. Garland, Notes from a Talk by General Chetlain, n.d., HGP; USG to Mary Grant, April 29, 1861, PUSG, 2:13-14; USG to Jesse Root Grant, May 2, 1861, PUSG, 2:18.

20. USG to Julia Dent Grant, May 3, 1861, PUSG, 2:19-20.

21. USG to Julia Dent Grant, May 6, 1861, PUSG, 2:24; USG to Jesse Root Grant, May 6, 1861, PUSG, 2:22.

22. USG to Julia Dent Grant, May 6, 1861, PUSG, 2:24. There is some evidence that suggests USG believed that a combined Union and Confederate force to put down a slave revolt would be, for the participating Federal forces, tantamount to treason against the United States. It is not known why he may have thought this or made this hair-splitting distinction. See Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity (Boston, 2000), 83. On USG’s ownership and emancipation of William Jones and USG’s racial views, see Nicholas W. Sacco, “‘I Never Was an Abolitionist’: Ulysses S. Grant and Slavery, 1854–1863,” Journal of the Civil War Era, 9 (September 2019): 410–437.

23. USG to Lorenzo Thomas, May 24, 1861, in PUSG, 2:35-36; Garland, Notes from a Talk by General Chetlain, n.d., HGP.

24. Quoted in John Russell Young, Around the World with General Grant, 2 vols. (New York, 1879), 2:214–215.

25. “Maj. Gen. G. B. McClellan,” Illinois State Register, June 17, 1861.

26. James E. Smith, quoted in George W. Pepper, Personal Recollections of Sherman’s Campaigns in Georgia and the Carolinas (Zanesville, OH, 1866), 392. For some of USG’s orders, see PUSG, 2:45-48, 52, 54-58.

27. S.C. Burroughs, Interview, ca. 1896-1897, HGP; Philip Welshimer to Julia Pickering Welshimer, June 25, 1861, Welshimer Papers, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Springfield, IL; “Camp Yates,” Illinois State Register, June 22, 1861.

28. Abraham Lincoln to Simon Cameron, July 30, 1861, in Roy P. Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ, 1953), 8:593–594; Simon Cameron to Lincoln, July 31, 1861, Record Group 46, Entry 550: 37th Congress, 1861-1863, President’s Messages—Executive Nominations, 1861-1863, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Senate Executive Journal, August 1, 1861, 497–498, August 3, 1861, 533–534, August 5, 1861, 554–548.

29. James L. Crane, “Grant as a Colonel,” McClure’s Magazine, 7 (June 1896): 43; “From Northeast Missouri,” Missouri Democrat, August 3, 1861.

Related topics: Ulysses S. Grant