Harper's Weekly

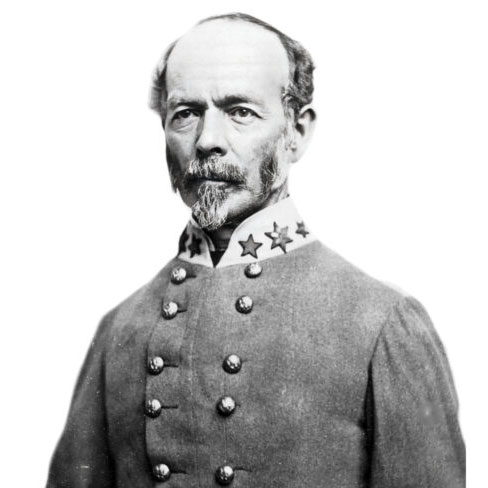

Harper's WeeklyUnion soldiers play cards—a bottle of liquor within reach—while they pose for a photograph.

Forty rod | noun | Whiskey; specifically, spirit of so fiery a nature that it is calculated to kill at Forty Rods’ distance, i.e. on sight.1

In January 1737, The Pennsylvania Gazette published “The Drinker’s Dictionary.” Some of its 228 terms might be familiar to an adult who imbibes today: “boozy,” “buzzey,” “fuddled,” “flush’d,” “intoxicated,” “limber,” “mellow,” and “tipsey.” Other phrases would be unintelligible to a modern American—be they drunk or sober. Unlike our 18th-century forefathers, we no longer describe drunkenness as “half way to Concord,” “nimptopsical,” or “knows not the way home.”2

Early Americans had become heavy drinkers. At its peak in 1830, annual alcohol consumption reached 4 gallons per capita. And not all Americans drank their share—some were teetotalers and moderate drinkers. Half the adult male population consumed two-thirds of all distilled spirits. White fathers taught their sons to drink. “I have frequently seen Fathers wake their Child of a year old from a sound sleap to make it drink Rum, or Brandy,” remarked one traveler.3 In the 1820s, an 8-year-old boy in Hartford, Connecticut, “called for an antifogmatic, which he drank off at one swallow, after which he lighted a cigar and amused himself with singeing.”4 Drinking alcohol was a marker of manhood.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Americans most often drank alcohol at home or work, and it could be consumed throughout the day. Some people imbibed before breakfast. This particular morning tipple developed its own term: “antifogmatic.”5 As one writer later noted, “in eighteenth century Philadelphia the misguided drank rum ‘to keep the fog out of their throats.’ Hence, rum was called ‘antifogmatic.’”6 At the time, alcohol was largely believed to hold medicinal properties and a bit of rum “nullified the effects of the early morning fog upon the general system.”7 A bit of booze on an empty stomach warmed the body and induced hunger. Common advice suggested that “the quantity taken every morning is in exact proportion to the thickness of the fog.”8

The United States military endorsed the practice, and in 1782 began to issue a daily gill (four ounces) of whiskey to soldiers. General George Washington approved of the ration, claiming “the benefits arising from moderate use of strong Liquor have been experienced in all Armies, and are not to be disputed.” But most soldiers consumed far more than that moderate amount. In 1830, the army purchased 72,537 gallons of whiskey at a cost of $22,132, which averaged to around 13.6 gallons per soldier. The growing temperance movement advocated against the practice, and Congress began restricting soldiers’ access to alcohol. On November 5, 1832, the adjutant general issued General Order 100, which eliminated the whiskey ration for most enlisted men. With the exception of those on fatigue duty or in hospitals, soldiers received only tea or coffee. According to some officers, ending the whiskey ration had done a “great good to the service, and the means of preserving the health, efficiency, and happiness, and frequently effecting the moral reformation of that part of our army.”9

Neither the temperance movement nor the official demise of the daily whiskey ration put an end to drinking or intoxication, though terms describing alcohol, drinking, and drunkenness changed. While men were still consuming rum before breakfast, fewer called it an “antifogmatic.” “This piece of verbal facetiousness was not [an] addition to the language, and lo! before the Civil War was fought, it had practically passed out of use—though we still have fogs and we still have rum,” wrote an American journalist.10 After swelling to near bursting, an 18th-century man so inebriated was said to be “tight as a tick.” By the mid-19th century, intoxicated people were simply “tight” or, more commonly, “drunk.” In 1860, Webster’s Dictionary defined tipsy as “fuddled; overpowered with strong drink; intoxicated.”11 Each of these terms, of course, meant different things; then as now, there was no single definition of drunkenness.

Alcohol use and misuse continued during the Civil War. While the whisky ration was not doled out daily on either side, officers did provide the occasional nip—anywhere from a dram to a full canteen—to soldiers on fatigue duty or serving in inhospitable conditions. After a day’s march through the rolling hills of Pennsylvania, “more or less inebriated and boisterous” Confederates fell into camp after “a very large ration of whiskey.”12 In the western theater, officers distributed whiskey “by [the] buckets-full” to some sodden soldiers, who “looked like drowned rats,” at a train depot in Montgomery, Alabama.13 While extremely popular among privates, officers issued these rations only on exceptional occasions. Over a two-year period, the men in the 43rd Mississippi Infantry received “but four rations” of whiskey.14 After six days of cold rain and snow, the 47th Alabama Infantry got “the first spirts that the gover ment had ever given to us.”15 Rarely, if ever, did men receive alcohol—sometimes labeled “liquid courage”—before going into battle.16

Soldiers could also procure their own drink and they imbibed liberally in camp. They asked their mothers, fathers, sisters, or wives to pack a bottle of brandy, whiskey, or cider and mail it to them at the front. Writing home in November 1862, Daniel Boyd requested a long list of supplies: a shirt, a pair of drawers, a jacket, three pairs of socks, a pair of boots, a hat, and “som Brandy.”17 Stationed at Fredericksburg, Confederate Private Richard Henry Brooks had “not drunk any Liquor since some time Last year nor I do not expect to drink a drink in a Long time.” The cost of alcohol—at one dollar per drink—kept him from imbibing.18 And as prices soared, quality plummeted. Private Sam Watkins described late wartime whiskey as a “nasty, greasy burning … going down my throat and chest, and smelling … like a decoction of redpepper tea, flavored with coal oil, turpentine, and tobacco juice.”19 Attempting to make merry on Christmas 1864, DeWitt Clinton Gallaher found “whiskey in Fishburn’s lumber room” and “later we got egg nogg at old John Mann’s little store.” But the holiday did not come off as expected. Instead of getting drunk, “all of us got sick! Whiskey in those days was enough to make anybody sick.”20

This bad booze had a special name: “forty-rod whiskey.” While its origins are as murky as the drink’s ingredients, the term first appeared in print around the time of the Civil War. The concoction had no precise recipe; distillers and homebrewers added assorted ingredients, adapting as wartime rationing limited the availability of corn and grain. The resulting elixir packed a punch. According to a veteran, “‘forty-rod-whiskey’ took its name from the effect it produced upon those who smacked their lips over it. After quaffing the zephyr-like ambrosia it has the angelic faculty of making a fellow feel as if he were forty rods from the place of his real existence. In short, he is distant from his equilibrium, and usually makes a desperate effort to restore himself.”21 Other descriptions are less sentimental. In theory, this nasty whiskey killed as effectively as a shotgun at forty rods (220 yards). Having drunk it, men felt “exceedingly sick, dejected, and crestfallen…. Their cries for water were incessant to allay the internal fires caused by ‘forty-rod.’”22

After the war, forty rod continued to be served in saloons out West. Meanwhile, the prohibition movement gained momentum in the 1870s and 1880s. Hatchet in hand, Carrie Nation preached temperance and stormed barrooms in Kansas and Missouri. In an effort to prevent crime, curb vice, and instill morality in their citizenry, states and cities across America began regulating the production and consumption of liquor. In January 1919, the United States ratified the Eighteenth Amendment, prohibiting “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.”23 Far from preventing drinking, Prohibition instead unleashed barrels of badly distilled and vile tasting spirits called “moonshine”—relegating forty rod to a bygone era.

Tracy L. Barnett is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia. Her dissertation analyzes the historical origins of America’s gun culture and its mutually constitutive relationship to white supremacist ideology. As the Digital Humanities Research Fellow, she worked as a research assistant for Private Voices, a website devoted to Civil War language.

Notes

1. John Stephen Farmer and William Ernest Henley, Slang and Its Analogues Past and Present, Vol. III (1893), 61.

2. This article is most often attributed to Benjamin Franklin. “The Drinker’s Dictionary,” The Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia), January 6, 1737.

3. W.J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York, 1979), 10–11, 14.

4. James Kirke Paulding, John Bull in America: Or, The New Munchausen (New York, 1825), 20.

5. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic, 16–19.

6. Warren Barton Blake, “Some Americanisms,” The Book News Monthly Vol 34 (1916): 112.

7. W.W. Hall, Health by Good Living (New York, 1871), 14.

8. Frank Vizetelly and Leander Jan De Bekker, A Desk-book of Idioms and Idiomatic Phrases in English Speech and Literature (New York, 1923), 13.

9. Mark A. Vargas, “The Progressive Agent of Mischief: The Whiskey Ration and Temperance in the United States Army,” The Historian Vol. 67, No. 2 (May 2005): 204, 214–215.

10. Warren Barton Blake, “Some Americanisms,” The Book News Monthly, Vol 34 (1916): 112.

11. Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language (Springfield, 1860).

12. Robert G. Evans, The 16th Mississippi Infantry (Jackson, 2002), 173.

13. William C. Davis, Diary of a Confederate Soldier: John S. Jackson of Orphan Brigade (Columbia, 1990), 76.

14. Mary Miles Jones and Leslie Jones Martin, eds., The Gentle Rebel: The Civil War letters of 1st Lt. William Harvey Berryhill… (Yazoo, MS, 1982), 33.

15. February 26, 1863, E.B. Coggin Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History.

16. “Liquid courage” did not motivate soldiers to go into battle. James McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (New York, 1997), 52–53.

17. November 14, 1862, Daniel Boyd to Robert Boyd, Private Voices (altchive.org/node/10754).

18. Katherine Holland, ed., Keep All My Letters: The Civil War Letters of Richard Henry Brooks, 51st Georgia Infantry (Macon, 2003), 69–70.

19. Sam R. Watkins, Co. Aytch: A Confederate Memoir of the Civil War (New York, 2008), 173.

20. December 26, 1864, “Augusta County: Diary of DeWitt Clinton Gallaher (1864–1865),” The Valley of the Shadow, University of Virginia.

21. Washington Davis, Camp-fire Chats of the Civil War (Chicago, 1888), 89.

22. Sir William Howard Russell, My Diary North and South (Boston, 1863), 1: 302.

23. U.S. Constitution, amend. 18, sec. 1.

Related topics: food and drink