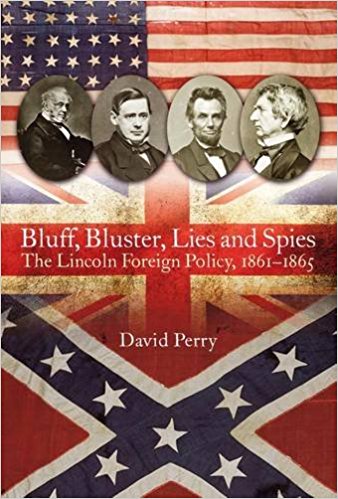

Bluff, Bluster, Lies and Spies: The Lincoln Foreign Policy, 1861–1865 by David Perry. Casemate, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 9781612003627. $32.95.

In this book, the author takes on one of the more fascinating—and too-often overlooked—subjects of Civil War history: diplomacy, foreign relations, and the very interesting cast of characters on both sides of the Atlantic responsible for determining foreign policy. Most Civil War historians, he points out, treat the Civil War as a purely military conflict without considering the vital role of diplomacy. Had Britain, France, or Spain been willing to recognize the Confederacy as a sovereign nation, it would have forced the United States either to declare war on one or several European Powers or give up the game and accept Southern independence. Often, the fate of separatist movements is decided not on the field of battle, but in the marble courts of diplomacy, where third parties decide whether or not to intervene militarily or mediate peace on terms of separation. Rebel separatists need not win military; they need only hold out until other nations with an interest in the conflict come to their rescue. The material interests of Europe in resuming the commerce in Southern Cotton, so Confederate leaders confidently assumed, would be enough to compel intervention. They were wrong, but this was by no means a foregone conclusion until very late in the war.

In this book, the author takes on one of the more fascinating—and too-often overlooked—subjects of Civil War history: diplomacy, foreign relations, and the very interesting cast of characters on both sides of the Atlantic responsible for determining foreign policy. Most Civil War historians, he points out, treat the Civil War as a purely military conflict without considering the vital role of diplomacy. Had Britain, France, or Spain been willing to recognize the Confederacy as a sovereign nation, it would have forced the United States either to declare war on one or several European Powers or give up the game and accept Southern independence. Often, the fate of separatist movements is decided not on the field of battle, but in the marble courts of diplomacy, where third parties decide whether or not to intervene militarily or mediate peace on terms of separation. Rebel separatists need not win military; they need only hold out until other nations with an interest in the conflict come to their rescue. The material interests of Europe in resuming the commerce in Southern Cotton, so Confederate leaders confidently assumed, would be enough to compel intervention. They were wrong, but this was by no means a foregone conclusion until very late in the war.

William Henry Seward, Lincoln’s Secretary of State, was terrified that Britain and France would move quickly to bring the war to an end on terms of separation. In May 1861, within days of learning about Fort Sumter, Britain recognized the Confederacy as a belligerent in a real war, the first step toward full recognition of sovereignty. France, the Netherlands, Spain, Belgium, Portugal, Brazil, even Hawaii followed Britain’s lead.

Seward took the position that this was not a war between nation states, and that the “so-called Confederacy” was nothing more than a domestic insurrection and not the business of foreign powers. He repeatedly warned Europe that if any nation dared to lend support of any kind to this rebellion, the United States would consider this an act of war. “We will wrap the whole world in flames!” he told astonished journalists and diplomats at dinner parties in Washington. “No power is so remote that she will not feel the fire of our battle and be burned by our conflagration,” he wrote to his ministers in Europe. This civil war “would “become a war of continents—a war of the world.”

Perry is intrigued by Seward’s bellicose words, and throughout the book, he seems unsure whether to evaluate it as shrewd strategy or simply foolish, empty bluster. A former professor of American history at the University of New Haven, Perry has published essays on related topics, and his notes indicate awareness of the recent scholarship on his chosen subject. But he often approaches his subject as though his questions about Seward’s strategy and mental health had not been investigated by earlier scholars.

“Was Seward crazy like a fox or just plain crazy?” he repeatedly asks, seeming never to get closer to a satisfactory answer. In several places, he seems willing to accept the doubtful claim that Charles Sumner, Seward’s arch-rival and chair of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, was the “de facto Secretary of State.” Perry supposes that Seward’s “April Fool’s Day memorandum,” as Seward’s critics fashioned it, caused Lincoln to spurn Seward and turn to Sumner for wise counsel.

In the memo, Seward warned Lincoln that Spain’s recent invasion of the Dominican Republic, if not challenged, would be the first step of many as predatory European empires took advantage of America’s debacle to take back lost empires. It appeared to be a power grab by Seward who, at least in the first month of Lincoln’s term, considered the president not up to the task. Lincoln firmly turned back Seward’s impatient call for foreign war, but Seward continued to enjoy free reign to pursue his hard power strategies against European intervention. If anything, his warning that Spain’s unanswered aggression against the Dominican Republic might lead to further European aggression proved prescient as Spain, France, and Britain launched an allied invasion of Mexico later in 1861.

In this and other tales of jealous rivalry on Seward’s part, historians have too often portrayed a bellicose, intemperate, and foolish Seward as a hapless foil to illustrate Lincoln’s even-tempered sagacity and instinctive understanding of things. Norman B. Ferris tried to set this right in his convincing reassessment of Seward as an astute secretary of state who fashioned a successful foreign policy in full concert with Lincoln’s domestic policy (Desperate Diplomacy, 1976, and his 1999 essay “Lincoln and Seward in Civil War Diplomacy”). More recently, Walter Stahr has offered a convincing case for Seward’s abilities in Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man (2012). My evaluation of the foreign reception of Seward’s foreign policy (The Cause of All Nations, 2015) argued that he, along with an able corps of diplomats, virtually invented public diplomacy by introducing the first state-sponsored program to influence public opinion abroad. In the end, one must measure Seward’s success by the failure of the Confederacy to win international recognition.

Perry has sprinkled his account with colorful anecdotes, great quotes, and flashes of keen insight, which will keep readers engaged. He has an unfortunate tendency to repeat himself, often by raising rhetorical questions about Seward’s effectiveness that are left unanswered.

Don H. Doyle, is the author of The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War (Basic, 2015). He is currently writing an international history of America’s Reconstruction era.