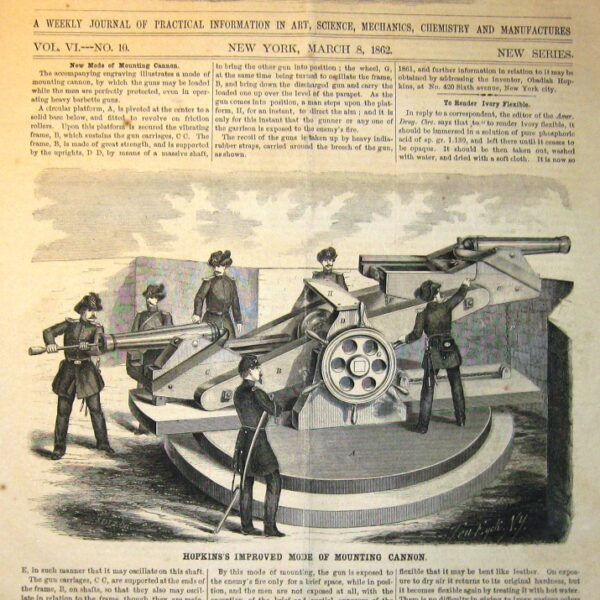

Belle Boyd

In July 1861, only months after the outbreak of the Civil War, Belle Boyd—the 17-year-old daughter of a prosperous family in Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia)—experienced a traumatic event that helped spur her to become a spy for the Confederacy. Boyd told the story of the incident—excerpted below—in her 1865 autobiography, Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison, a book considered by historians to include a mix of fact, fiction, and exaggeration. Boyd would go on to become one of the conflict’s most notorious Rebel spies, using her considerable charms to obtain important information from a variety of Union officers. By 1864, Boyd, who had been arrested at least six times for her activities, made her way to England. She returned to America in 1866 and died in 1900 at age 56, having married three times and had five children during her lifetime.

The morning of the 4th of July dawned brightly.

I need hardly say, for it is well known, that the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence has, in each succeeding year from that of its birth, been hailed with triumphant acclamations by a nation still too young to moderate its transports and lend its ear to the voice of reason rather than to the impulse of passion.

The Yankees were in undisputed possession of Martinsburg; the village was at their mercy, and consequently entitled to their forbearance; and it would at least have been more dignified in them had they been content to enjoy their almost bloodless conquest with moderation; but, whatever might have been the intentions of the officers, they had not the inclination, or they lacked the authority, to control the turbulence of their men.

The severance of the North from the South had now become in feeling so complete, that we Martinsburg girls saw the Union flag streaming from the windows of the houses with emotions akin to those with which the ladies of England would gaze upon the tri-color of France or the eagle of Russia floating above the keep of Windsor Castle. Those hateful strains of “Yankee Doodle” resounded in every street, with an accompaniment of cheers, shouts, and imprecations.

Whiskey now began to flow freely; for, amid the motley crowd of Americans, Dutchmen, and other nations, the Irish element predominated. The sprigs of shillelahs were soon at work, and the “sons of Erin” proved that they could use their sticks with no less effect in an American town than at an Irish fair. They set at defiance the authority of those among their officers who vainly interposed to quell the tumult and restrain the lawless violence that was offered to defenceless citizens and women.

The Boyd House in Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), as it appeared in 2015

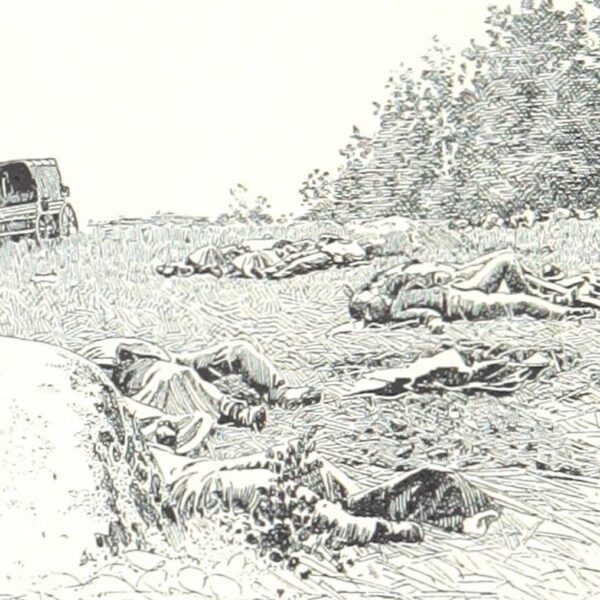

The doors of our houses were dashed in; our rooms were forcibly entered by soldiers who might literally be termed “mad drunk,” for I can think of no other expression so applicable to their condition. Glass and fragile property of all kinds was wantonly destroyed. They found our homes scenes of comfort, in some cases even of luxury; they left them mere wrecks, utterly despoiled and mutilated. Shots were fired through the windows; chairs and tables were hurled into the street.

In some instances a trembling lady would make a timid appeal to that honor which should be the attribute of every soldier, or, with streaming eyes and passionate accents plead for some cherished object—the portrait, probably, of a dead father, or the miniature her lover placed in her hand when he left her to fight for his freedom and hers—upon which many a secret kiss had been pressed, many a silent tear had fallen, before which many an earnest prayer had been breathed.

To such applications the reply was invariably a volley of blasphemous curses and horrid imprecations. Words from which the mind recoils with horror, which no man with one spark of feeling would utter in the presence even of the most abandoned woman, were shouted in the ears of innocent, shrinking girls; and the soldiers of the Union showed a malignant, a fiendish delight in destroying the effigies of enemies whom they had not yet dared to meet upon equal terms in an open field of battle.

Surely it is not strange that cruelties such as I have attempted to describe have exasperated our women no less than our men, and inspired them with sterner feelings than those which inflame the bosoms of ladies who know nothing of invasion but its name, who have never at their own firesides shuddered at the oaths and threats of a robber disguised in the garb of a soldier.

Shall I be ashamed to confess that I recall without one shadow of remorse the act by which I saved my mother from insult, perhaps from death—that the blood I then shed has left no stain on my soul, imposed no burden upon my conscience?

The encounter to which I refer was brought about as follows:— A party of soldiers, conspicuous, even on that day, for violence, broke into our house and commenced their depredations; this occupation, however, they presently discontinued, for the purpose of hunting for “rebel flags,” with which they had been informed my room was decorated. Fortunately for us, although without my orders, my negro maid promptly rushed up-stairs, tore down the obnoxious emblem, and before our enemies could get possession of it, burned it.

They had brought with them a large Federal flag, which they were now preparing to hoist over our roof in token of our submission to their authority; but to this my mother would not consent. Stepping forward with a firm step, she said, very quietly, but resolutely, “Men, every member of my household will die before that flag shall be raised over us.”

Upon this, one of the soldiers, thrusting himself forward, addressed my mother and myself in language as offensive as it is possible to conceive. I could stand it no longer; my indignation was roused beyond control; my blood was literally boiling in my veins; I drew out my pistol [*All our male relatives being with the army, we ladies were obliged to go armed to protect ourselves as best we might from insult and outrage] and shot him. He was carried away mortally wounded, and soon after expired.

Our persecutors now left the house, and we were in hopes we had got rid of them, when one of the servants, rushing in, cried out—

“Oh, missus, missus, dere gwine to burn de house down; dere pilin’ de stuff ag’in it! Oh, if massa were back!”

The prospect of being burned alive naturally terrified us, and, as a last resource, I contrived to get a message conveyed to the Federal officer in command. He exerted himself with effect, and had the incendiaries arrested before they could execute their horrible purpose.

In the mean time it had been reported at head-quarters that I had shot a Yankee soldier, and great was the indignation at first felt and expressed against me. Soon, however, the commanding officer, with several of his staff, called at our house to investigate the affair. He examined the witnesses, and inquired into all the circumstances with strict impartiality, and finally said I had “done perfectly right.” He immediately sent for a guard to head-quarters, where the elite of the army was stationed, and a tolerable state of discipline preserved.

Sentries were now placed around the house, and Federal officers called every day to inquire if we had any complaint to make of their behavior. It was in this way that I became acquainted with so many of them; an acquaintance “the rebel spy” did not fail to turn to account on more than one occasion.

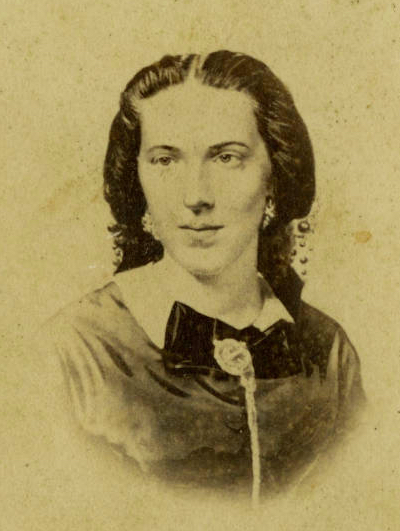

Confederate spy Belle Boyd

When the news reached the Confederate camp at Darksville, seven miles from Martinsburg, on the Valley Road, that I had shot a Yankee soldier in self-defence, together with the false report that for so doing I had been thrown into the town jail, the soldiers with one accord volunteered to storm the prison and rescue me, or die to a man in the attempt. It is with pride and gratitude that I record this proof of their esteem and respect for what I had done. It is with no less pleasure I reflect that their devotion was not put to the test, and that no blood was shed on my account….

Meanwhile, my residence within the Federal lines, and my acquaintance with so many of the officers, the origin of which I have already mentioned, enabled me to gain much important information as to the position and designs of the enemy. Whatever I heard I regularly and carefully committed to paper, and whenever an opportunity offered I sent my secret dispatch by a trusty messenger to General J. E. B. Stuart, or some brave officer in command of the Confederate troops. Through accident or by treachery one of these missives fell into the Yankees’ hands. It was not written in cipher, and, moreover, my handwriting was identified. I was immediately summoned to appear before some colonel, whose name I have forgotten; but I remember it was Captain Gwyne who escorted me to head-quarters. There I was alternately threatened and reprimanded, and finally the following “Article of War” was read to me in a most emphatic manner, and with the caution that it would be carried out in the spirit and the letter:—

“Article of War. Whoever shall give food, ammunition, information to, or aid* and abet the enemies of the United States Government in any manner whatever, shall suffer death, or whatever penalty the honorable members of the court-martial shall see fit to inflict.”

[*I had been confiscating and concealing their pistols and swords on every possible occasion, and many an officer, looking about everywhere for his missing weapons, little dreamed who it was that had taken them, or that they had been smuggled away to the Confederate camp, and were actually in the hands of their enemies, to be used against themselves.]

I was not frightened…. I listened quietly to the recital of the doom which was to be my reward for adhering to the traditions of my youth and the cause of my country, made a low bow, and, with a sarcastic “Thank you, gentlemen of the Jury,” I departed; not in peace, however, for my little “rebel” heart was on fire, and I indulged in thoughts and plans of vengeance.

From this hour I was a “suspect,” and all the mischief done to the Federal cause was laid to my charge; and it is with unfeigned joy and true pride I confess that the suspicions of the enemy were far from being unfounded.

Related topics: women