Scott Roland stands on a corner of the fabled Gettysburg electric map in its new home in Hanover, Pennsylvania.

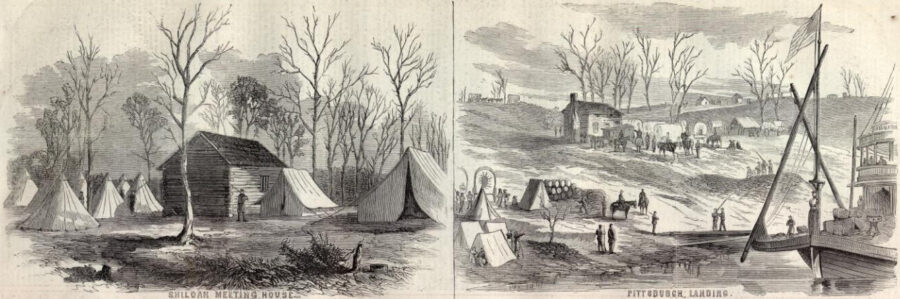

It was a sight that stopped traffic: a 10,000-pound chunk of plaster-on-steel, 27 feet long and seven feet wide, dangling in the air as a crane operator wormed it through the second-story window of a historic building in downtown Hanover, Pennsylvania. Over the course of 12 hours, three more equally sized blocks would follow. On the street below, a scrum of news crews and locals surveyed the progress, heads tilted upward. Orchestrating this heavy midair dance was Scott Roland, the new owner of these mammoth rectangles—the four pieces of the fabled Gettysburg electric map.

Ask any Civil War enthusiast older than 20 what they remember about their first visit to the Gettysburg Battlefield and they’ll probably pull up a memory of the electric map. Built in 1963 to mark the engagement’s centennial, the map told the story of the Battle of Gettysburg through a sequenced display of tiny lights—blue for Union troops, amber for Confederate—on a giant contoured model of the battlefield. During a 22-minute narrated show, visitors watched those lights shift and move across the miniaturized landscape, following along as units of troops advanced and retreated. For decades, the map served as one of the visitors center’s main attractions, orienting an estimated 60 to 70 million people to the details of the epic three-day battle. Some called it a national treasure.

In 2008, the visitors center was bulldozed to make way for a new one—and it looked like the map might go with it. Many felt the map was kitschy and outdated, ready for replacement by slicker, digital storytelling. “The last park superintendent to oversee it called it the ‘electric nap,’” says Roland. The map was also the size of a backyard swimming pool and as heavy as 10 midsize trucks. And yet its ability to help visitors understand the battle was legendary, bordering on mystical. Opposition to its obliteration was vehement. Ultimately, the Park Service spared its destruction but not its retirement. They used a demolition saw to cut the map into four parts, then stuck it in storage. It seemed like the end of its story, and the end of an era.

Scott Roland had seen the map as a kid, in the early 1970s. A native Pennsylvanian, he’d camped on the Gettysburg Battlefield with his Boy Scout troop, in pursuit of three coveted patches—one each for hiking the Union and Confederate lines, and a third for viewing the electric map. Roland still has the patches and can describe them in detail. Had the map’s blinking lights and thumb-size trees made a similar impression? Well, not exactly. “I remember it as something you had to do to get the patch, and not much beyond that,” he admits.

Opportunity, not memory, motivated Roland to acquire the map. A mechanical engineer, Roland worked for years in the electronic connector industry, manufacturing those tiny metal pieces at the end of phone chargers and thousands of other things like them. When he started out, Central Pennsylvania was the electronic connector capital of the world, home to industry giants like Amp, FCI, and Tyco. Roland worked his way up from production supervisor to owner of his own company, but then the whole industry shifted to China. He sold out of the connector business in 2007, at 45 years old.

Early retirement didn’t suit him. So he started buying real estate and restoring and repurposing empty historic buildings in Hanover. In mid-2012, Roland bought a 10,000-square-foot former bank in the heart of downtown. He wasn’t sure what to do with it. Then he saw a news story about the electric map going to auction. Somewhere in Roland’s brain, connectors connected. More than a million people visit Gettysburg each year. If a fraction were willing to drive just 15 more miles to see the map, it could bring a boom of tourism to Hanover, which, like many small towns, could use the business. Roland convinced an architect friend to meet him at the bank building, armed with a tape measure. “We determined the map would fit, but he thought I was nuts,” says Roland. “Probably still does.”

Then came the bigger question: Could he even get it? The auction was held online, and there were only two bidders—Roland and a man from Gettysburg. There was no viewing the map beforehand. On auction day, bidding started at $100 and climbed slowly. At the exact minute the auction was scheduled to end, Roland had the high bid at about $3,000. But there was a glitch. Somehow, the bidding kept going. Frenzy ensued. When the other bidder jumped to $10,000, Roland hit back with $14,010—then suddenly, the auction expired. And there he was, having paid an epic sum for four big nostalgic blocks of plaster, sight unseen.

A piece of the Gettysburg electric map is readied to move into its new home in Hanover, Pennsylvania.

Roland was given directions to a trucking yard some 25 miles away, and soon after that he was shining a flashlight into a giant shipping container for the first view of his purchase. Then came the spectacle of getting the pieces to Hanover and through the second-story window—a journey that drew national attention. “Our son was living in California, and our daughter was living in Florida,” says Roland. “They both called to say, what are you doing, Dad? You’re in the newspaper for moving a map.”

But the work was just getting started. The electric map had no control panel and no power supply. “The original map had been made with a bunch of leftover- type stuff—cut-up strands of Christmas lights and old telephone wire,” Roland says. Lighting it again would require at least a thousand new wires, and getting the map’s 635 lights to work on cue would require 7,000 connections. “There were no wiring diagrams, nothing,” says Roland. “We had to figure out what lights came on at the same time and what was what.” That an engineer with specialized knowledge of electrical connectors was the map’s new owner was starting to feel like fate.

Roland enlisted Greg Ruff, a friend from the connector business, to help him tackle the rewiring. “Greg volunteered—or volunteered is a little—maybe I conned him into helping rewire it,” says Roland. The map was on cinderblocks, 18 inches off the ground. They bought mechanics creepers—the wheeled trolleys you lie on to work under a car—and spent long hours rolling this way and that way under the map, running 2.5 miles of new wire. Meanwhile, Roland found a machine-controlled computer on eBay—to serve as the map’s brain—and he and Ruff spent months learning how to program it.

The lights were a hassle. More than half of them didn’t work—and, it turns out, hadn’t worked even in the last few years the show was still running. “I watched a video someone made of one of the map’s last showings,” says Roland. “When the narrator talked about Little Round Top and how it went back and forth several times, nothing was going on with the lights. If you look at the physical map itself, the lights were there, but they didn’t work.” Some bulbs had been painted over, so Roland used an ultrasonic cleaner with brake fluid to take off the paint. Others had burned out or lost their connection.

About 20 percent of the map’s bulbs were missing, but replacements in their shape and size weren’t made anymore. Roland remembered a toy from his childhood—the Vac-U-Form machine, manufactured by Mattel in the 1960s, which let you heat up plastic and mold it into parts—and used a few he found on eBay to make bulbs that looked identical to the originals. Shading them Union blue or Confederate amber was the next hurdle. Roland recalled yet another 1960s toy—Dip-a-Flower, which came with a pre-colored dye formula that he thought would made the right colors. So he tracked down the toy’s UK-based manufacturer. The dye hadn’t been made for years, but they still had some. Improbably, their lone U.S. distributor was in Gettysburg. “It’s pretty difficult to tell the new bulbs from the original,” says Roland. “The whole project was an exercise in making what we didn’t have and learning what we didn’t know.”

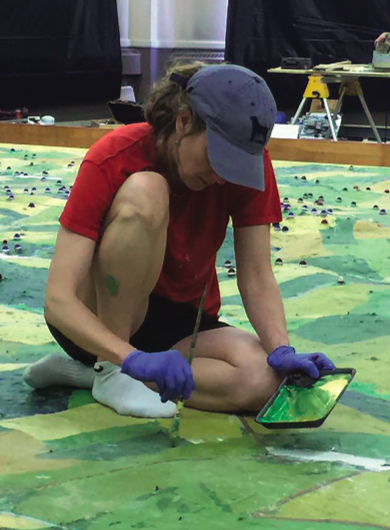

An artist works on the restoration of the Gettysburg electronic map after its move to its new home in Hanover, Pennsylvania.

Beyond repairs, Roland didn’t change the map’s appearance or function. “Some people suggested we could put trees and this, that, and the other on it, and we said no,” Roland says. He even resurrected the original narration, read by Joseph Rosensteel, the map’s creator, cleaning up the audio until it sounded almost unblemished. Over the decades, that narration had drawn fire for its simplicity, but some think it’s what made the map experience so effective. “Less is more, and the map is really like that,” says Marc Charisse, a York College of Pennsylvania professor who helped Roland on the project. “Rosensteel had a genius for the exact right amount of information.”

On June 3, 2016, the electric map reopened to the public in the newly dubbed Hanover Heritage & Conference Center. The TV crews came out again, and people waited in line for the first showing. The ones drawn there by nostalgia were not disappointed. “Some told me that the light show was far more compelling than they remember it,” says Roland. Just as satisfying were the map newbies who marveled—just as newbies had marveled for decades—that they hadn’t understood the Battle of Gettysburg until seeing the show. Thanks to Rosensteel, and now Roland, they got it.

After a strong first season, the electric map closed due to building permitting issues. “By the time word was getting out there, we were closing,” says Charisse, who ran the map show. Now he gets several calls a day, asking when the map will reopen. Good news: It is tentatively scheduled to reopen this spring, in time for the Gettysburg tourist season. “It’s a big deal to those who know about the map, remember it, and hold it dear,” says Roland. “It’s greater than just nostalgia. It is a piece of history in its own right.”

Jenny Johnston is a freelance writer and editor based in San Francisco.

This article appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of The Civil War Monitor.