Library of Congress

Library of CongressTheodore Roosevelt (left) and John Muir on Glacier Point, Yosemite Valley, California, in 1903.

In 1903, Theodore Roosevelt paid his first visit to the Yosemite Valley of California, with John Muir as his guide. For three days the president and the naturalist explored a landscape that impressed upon Roosevelt the need to conserve land in the American West, “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” Roosevelt later wrote that spending the night in Yosemite “was like lying in a great solemn cathedral, far vaster and more beautiful than any built by the hand of man.” He deemed it among the most beautiful places on earth, though he admitted that he was drawn to the “desolate and awful sublimity” of the Grand Canyon to a greater degree than to Hetch Hetchy or Half Dome. Splitting such hairs hardly mattered, however, as Roosevelt dedicated himself to the task of urging Americans to preserve and protect such sites for their children and their children’s children to observe in all their grandeur.

Just three years later, Roosevelt signed legislation creating the modern Yosemite National Park, unifying land held by the federal government and the state of California into a single wilderness monument. In 2023, nearly 4 million visitors passed through the park’s gates, seeking communion with nature and finding space removed from the maelstrom of modernity. Those of us who frequently visit our national parks think often of Roosevelt and his propulsive energy for preservation. America’s greatest idea—as the National Park System has come to be known—was born, in part, out of the 26th president’s own battle with the rapid industrialization of his era at the turn of the 20th century. Nature offered the antidote to the noise, machinery, and unceasing industrial development that threatened to raze the wilderness in pursuit of profit.

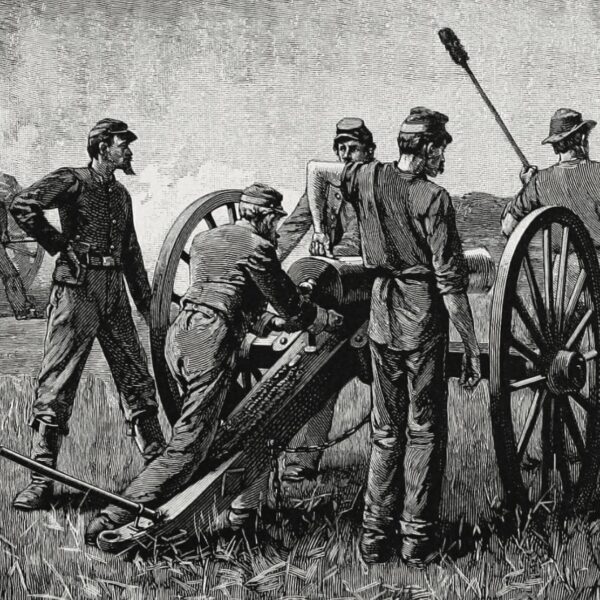

The American West with its grand natural spaces has long served as a panacea for the nation’s anxieties. But it was not Roosevelt who first saw this possibility in Yosemite, it was Abraham Lincoln, who as the 16th president stood at the center of the greatest crisis in his country’s history. The cacophony of the Civil War, after all, could hardly have been surpassed by the clanging of factory machinery or the chugging of railroad engines that multiplied in the next national age. In early summer 1864, as reports from the fighting at Kennesaw Mountain poured into the war office and Ulysses S. Grant settled the Army of the Potomac into its lines at Petersburg, Lincoln found the Yosemite Valley Grant Act awaiting his approval. His signature on the legislation marked the first time the federal government had reserved land from private ownership, for “public use, resort, and recreation.”

Lincoln and his fellow Republicans spent much of the Civil War thinking about the West’s potential to provide succor for the wounds of war inflicted on the body politic. Their imaginations were aided by the new artistic medium of photography, which allowed Americans to contemplate still images of scenes they might never witness for themselves—or might have lived through under fire. And so, in 1864, gallerygoers in New York, Philadelphia, or Washington, D.C., could view the horrifying images of swollen and mutilated bodies splayed across the rolling farmland of Adams County, Pennsylvania, and in the same gallery, staggering vistas of cascading waterfalls and towering sequoias in faraway California.

Library of Congress

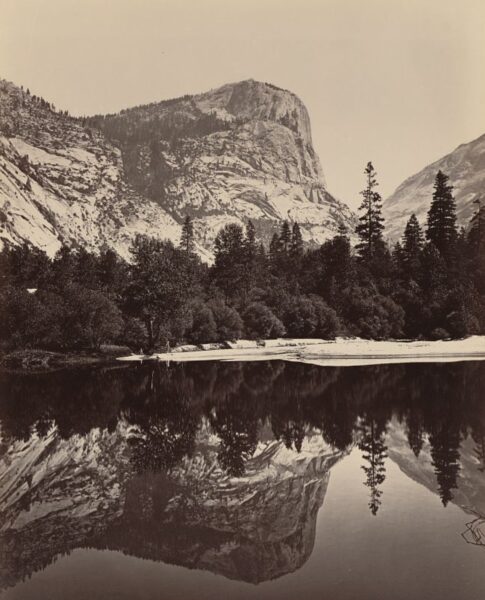

Library of CongressPhotographer Carleton Watkins made this image of Mirror Lake in Yosemite in the 1860s.

Though the most famous images of Yosemite emerged through the lenses of celebrated artists such as Ansel Adams in the 1920s (Yosemite was transferred to NPS jurisdiction in 1916), the earliest images of the region date from just before the Civil War. Just as Mathew Brady’s and Alexander Gardner’s images would find their way from battlefield to homefront, so portfolios of Carleton Watkins’ plates and stereo views of Yosemite made in 1861 were sent back east in 1862 and exhibited in New York. There the German American painter Albert Bierstadt saw them and, after securing the patronage of California railroad barons Leland Stanford and Collis Huntington, set out to paint the valley for himself the next year. The canvases he began on that trip, which now hang in museums across the world, remain some of the most indelible depictions of the American wilderness ever produced.

When Frederick Law Olmsted wrote the first report on the condition of Yosemite in 1865, a year after the park’s creation, he credited imagery above all else for the passage of the legislation that protected the land. He also gestured to the importance of the idea of the West in drawing Americans out of the miasma of suffering they had endured in the Civil War. “It was during one of the darkest hours,” Olmsted wrote, “before Sherman had begun the march upon Atlanta or Grant his terrible movement through the Wilderness when the paintings of Bierstadt and the photographs of Watkins, both productions of the war time, had given to the people on the Atlantic some idea of the sublimity of the Yosemite.” It was the antidote to the “mighty scourge of war” that had engulfed the nation—the West was a place in which the great postbellum work Lincoln anticipated, “to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have born the battle,” could occur.

The westward inclination of the Civil War generation insured that California’s Yosemite Valley would never endure the scarring and burning of Virginia’s Shenandoah. No armies would ever march, camp, and fight on the slopes of El Capitan as they did at Cedar Mountain. Thousands of veterans moved west after the war, taking advantage of other Lincoln administration legislation, such as the Homestead Act, to turn their swords into ploughshares. More than 11,000 Union veterans are buried in Los Angeles National Cemetery, with another 500 in Seattle’s Grand Army of the Republic cemetery. Though we may never know how these veterans interacted with sites such as Yosemite—or the national parks that began to populate the West after President Grant protected Yellowstone as the first such space in 1872, we can safely suggest that Lincoln and his contemporaries set the West apart for future generations, even before the great work of the Civil War had come to a close.

Cecily Zander is an assistant professor of History at Texas Woman’s University and a senior fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. She is the author of The Army under Fire: Antimilitarism in the Civil War Era (LSU Press, 2024). She is at work on a study of Abraham Lincoln and the American West, to be published by Liveright.

Related topics: Abraham Lincoln