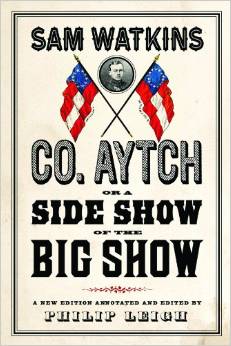

Co. Aytch, or a Side Show of the Big Show by Sam Watkins and edited by Philip Leigh. Westholme Publishing, 2014. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1594161797. $14.95.

Sam Watkins’ Co. Aytch has long been regarded as one of the finest memoirs written by a common soldier of the American Civil War. Watkins, who was born near Columbia, Tennessee, in 1839, enlisted in Company H of the First Tennessee Infantry (Confederate) in the spring of 1861. Over the next four years, he participated in a number of major military engagements, including those at Shiloh, Corinth, Perryville, Murfreesboro, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, Kennesaw Mountain, Atlanta, Franklin, and Nashville. When the Army of Tennessee surrendered in the spring of 1865, Watkins was one of only seven men to survive service in “Co. Aytch.” Fifteen years later he penned his war memoir, which was first serialized in his hometown Columbia Herald in the early 1880s. Though it was subsequently published in several book-length editions, Co. Aytch remained relatively unknown outside of specialist circles until 1990, when Ken Burns’ documentary The Civil War highlighted Watkins’ wartime experiences and quoted from his memoir. Since then, numerous editions of Co. Aytch have appeared, though Philip Leigh’s latest edition from Westholme Publishing is the first that is both illustrated and fully annotated.

Sam Watkins’ Co. Aytch has long been regarded as one of the finest memoirs written by a common soldier of the American Civil War. Watkins, who was born near Columbia, Tennessee, in 1839, enlisted in Company H of the First Tennessee Infantry (Confederate) in the spring of 1861. Over the next four years, he participated in a number of major military engagements, including those at Shiloh, Corinth, Perryville, Murfreesboro, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, Kennesaw Mountain, Atlanta, Franklin, and Nashville. When the Army of Tennessee surrendered in the spring of 1865, Watkins was one of only seven men to survive service in “Co. Aytch.” Fifteen years later he penned his war memoir, which was first serialized in his hometown Columbia Herald in the early 1880s. Though it was subsequently published in several book-length editions, Co. Aytch remained relatively unknown outside of specialist circles until 1990, when Ken Burns’ documentary The Civil War highlighted Watkins’ wartime experiences and quoted from his memoir. Since then, numerous editions of Co. Aytch have appeared, though Philip Leigh’s latest edition from Westholme Publishing is the first that is both illustrated and fully annotated.

Leigh, an independent historian and regular contributor to the New York Times’ “Disunion” blog, has provided over 240 annotations, 23 maps, and 17 illustrations and photographs “to help readers visualize the events, people, and places Sam experienced in his four years as an ordinary Confederate soldier” (xi). Leigh’s goal was to make Co. Aytch accessible to non-specialists, and he has largely succeeded in doing so. His six-page introduction contains a short biography of Watkins, as well as an overview of Civil War army organization. The maps, drawn by Civil War cartographer Hal Jespersen, depict Company H’s major movements and engagements over the course of the war.

Leigh’s annotations, aimed primarily at a popular readership, frequently refer to these maps. They likewise identify most of the major people and places that Watkins referenced but did not fully explain. The editor’s footnotes also define a number of contemporary terms that Watkins used which might not be familiar to twenty-first century readers, including “Dutchman” (19), “roastingears” (51), and “larking” (95), as well as military terms like Napoleon gun (xx), vedette (4), the “long-roll” drum signal (14), Whitworth sharpshooters (144), and the “hollow square” infantry formation (157). Watkins frequently referenced Bible verses, Greek myths, and Roman history in his memoir, and Leigh dutifully explains these allusions and places them in proper context. He incorrectly identifies Roman consul Gaius Marius as “the Roman conqueror of Carthage” (265), but otherwise, his annotations are quite helpful.

Leigh’s battle overviews are his most significant contribution to this edition of Co. Aytch; he provides lengthy notes detailing all of the First Tennessee’s major engagements — in some cases explaining exactly where Watkins likely stood on the battlefield and what role, if any, Company H played in the fighting. Consequently, readers unfamiliar with the major battles in the Western Theater should still be able to understand and appreciate most of Watkins’ riveting (and oftentimes humorous) account.

The most significant parts of the book are not, however, Watkins’ discussions of battles. Rather, they are his vivid depictions of the “poor old Rebel webfoot private soldiers” (228) and the daily minutiae of soldiering. Thanks to Watkins, we know that the soldiers of Company H, like many common Civil War soldiers, foraged for corn and hogs, played poker and “chuck-a-luck” in camp (82), gawked at pretty girls, plundered civilian homes, ate rats and other varmints, longed for home, struggled to stay awake while on picket duty, suffered in hospitals, and tragically watched their comrades die. Watkins continuously reminded his readers that he did not aim to write history; rather, he sought only to convey his “own impressions” of the war (47), which represented only “a few sketches and incidents that came under the observation of a ‘high private’ in the rear ranks of the rebel army” (4), recorded “entirely from memory” some twenty years after the fighting (63). Thus, he self-effacingly claimed, people seeking authoritative battle narratives or stories “of great achievements of great men” (4) should “see the histories for that” (16). Unlike his elite contemporaries, Watkins aspired to depict the “fellows who did the shooting and killing, the fortifying and ditching, the sweeping of the streets, the drilling, the standing guard, picket and videt, and who drew . . . eleven dollars per month and rations, and also drew the ramrod and tore the cartridge” (4). Watkins undoubtedly achieved his objective, and it is because of this that his book remains relevant today. Undergraduate Civil War instructors looking for a Civil War memoir that captures “the real war” with a grace and humor that even Mark Twain could appreciate would be wise to consider Philip Leigh’s new edition of Co. Aytch.

David Schieffler is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Arkansas.