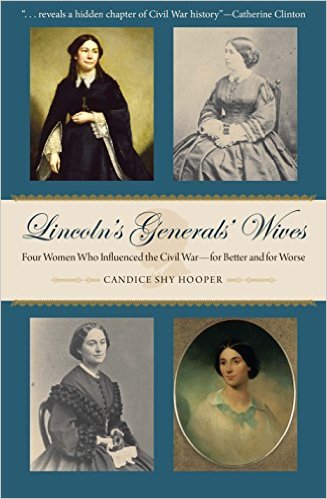

Lincoln’s Generals’ Wives: Four Women Who Influenced the Civil War—for Better and for Worse by Candice Shy Hooper. Kent State University Press, 2016. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1-60635-278-6. $39.95.

In this intricate comparative analysis, Candice Shy Hooper explores how Jessie Benton Fremont, Mary Ellen (“Nelly”) Marcy McClellan, Eleanor (“Ellen”) Ewing Sherman, and Julia Dent Grant motivated, guided, encouraged, and occasionally clashed with their famous husbands during the Civil War. Organized as a series of case studies and illustrated with photographs and distinctive maps, Lincoln’s Generals’ Wives provides an in-depth look at these women’s lives and their marriages as they evolved before, during, and after the war. Along the way, Hooper reviews in detail the military successes and failures of generals Fremont, McClellan, Sherman, and Grant. Hooper is particularly concerned with how each of the generals’ wives influenced her husband’s relationship with his commander-in-chief, President Abraham Lincoln.

In this intricate comparative analysis, Candice Shy Hooper explores how Jessie Benton Fremont, Mary Ellen (“Nelly”) Marcy McClellan, Eleanor (“Ellen”) Ewing Sherman, and Julia Dent Grant motivated, guided, encouraged, and occasionally clashed with their famous husbands during the Civil War. Organized as a series of case studies and illustrated with photographs and distinctive maps, Lincoln’s Generals’ Wives provides an in-depth look at these women’s lives and their marriages as they evolved before, during, and after the war. Along the way, Hooper reviews in detail the military successes and failures of generals Fremont, McClellan, Sherman, and Grant. Hooper is particularly concerned with how each of the generals’ wives influenced her husband’s relationship with his commander-in-chief, President Abraham Lincoln.

Hooper’s use of “for Better and for Worse” in the title of the book is not just clever word play. Ellen Sherman and Julia Grant clearly rose to the occasion of wartime spousal support and brought out the best in their husbands, while Jessie Fremont and Nelly McClellan did just the opposite. Hooper does not hide her disappointment in Fremont and McClellan, particularly the former, whose outspoken anti-slavery stance cemented her historical reputation in the nineteenth century.

Hooper’s section on Jessie Fremont is appropriately titled “Friendly Fire” and reflects the theme of Jessie’s propensity to encourage her husband John’s worst instincts for reckless decision-making and imperious leadership. Obviously devoted to her husband, Jessie played an active role in his Civil War generalship—to the extent that Hooper dubs her “his unofficial chief of staff” (5). Hooper reviews the various accounts of Jessie’s famously unsuccessful meeting with President Lincoln in September 1861 and determines that the incident revealed both faulty political instincts and poor judgement on her part. On the other hand, Hooper argues that Jessie deserves more credit than most historians have given her for her part in arranging for John Greenleaf Whittier to visit John Fremont in 1864 and convince him to withdraw from the presidential race. Hooper ultimately concludes that Jessie might have had a more positive influence on her husband’s career had she opposed him more often.

In the book’s introduction, Hooper writes that, “famous Jessie stands in stark contrast to obscure Nelly McClellan” (5). Like Jessie a strong-willed young woman, Nelly McClellan apparently squelched her independent streak after her marriage and wrapped herself in the garb of the subservient wife. Hooper writes that Nelly neither actively assisted her husband professionally nor contributed to the Union war effort in any demonstrable way. Because she left only a handful of writings behind, Nelly’s voice is more muted than that of the other women featured in Lincoln’s Generals’ Wives. As a result, the chapters about Nelly are often actually more about “Little Mac,” whom Hooper critiques with such pithy statements as “McClellan was always better at writing than fighting” (98). And write he certainly did—especially to Nelly. From the general’s revealing letters to Nelly, Hooper deduces that Nelly was McClellan’s “enabler,” reinforcing his character flaws of self-absorption, excessive pride, and paranoia and encouraging his distrust of President Lincoln (96).

In contrast to the somewhat one-sided portrayal of the McClellans’ marriage (based on the dearth of sources from Nelly’s viewpoint), Lincoln’s Generals’ Wives provides a nuanced interpretation of the relationship between Ellen and William T. Sherman, who saved many of his wife’s wartime letters. Hooper successfully depicts Ellen Sherman as a complex woman who was devoted to her husband, her father, the Catholic religion, and her country; Hooper emphasizes the intensity of Ellen’s hatred of secessionists and declares that she was “more Sherman than Sherman himself” (210). Hooper argues that while there was considerable tension within the Shermans’ marriage due to such issues as finances and his refusal to convert to Catholicism, Ellen proved to be a rock at low points in William’s military career. After the charge of insanity was leveled against him late in 1861, for example, she gave him essential emotional support, expressed her complete confidence in his abilities, set the formidable Ewing family clan to work on minimizing the damage, and directly corresponded with his superiors, including President Lincoln, on his behalf.

Like Ellen Sherman, Julia Grant was indispensable to her husband’s Civil War generalship. Hooper gets beneath the surface of the Grants’ storied lifelong love affair to show how critical Julia was to Ulysses’ ability to maintain his equilibrium in the maelstrom of war. “She was his center of gravity,” notes Hooper (310). Julia’s abject failure as a correspondent, which Hooper attributes in part to her eye defect of strabismus, convinced Ulysses to do everything in his power to have her with him in the field. Rallying to the occasion, Julia logged more than ten thousand miles from 1861 to 1865, prompting Hooper to dub her “the Civil War’s road warrior” (293). Hooper argues that in camp Julia served as a mediator between the general and his officers, but she focuses on how Julia’s cheerful disposition (which, unfortunately, does not come through in any of her photographs) contributed to Grant’s well-being throughout the war (he even asked her to refrain from visiting the wounded so that she would not speak to him of the horrors she encountered). Hooper emphasizes the importance of Julia’s insistence that her husband invite President Lincoln to City Point in March 1865, a visit that enabled Lincoln to get to Richmond quickly after it fell to Union forces.

Lincoln’s Generals’ Wives is a compelling read that will appeal to historians and laypeople alike. As a historian of women, I would have preferred more gender analysis and less detail on the generals’ careers. Yet, in the end, the focus of the book is on the lives of these four women as military wives. Hooper makes a strong case for their significance in that role during the Civil War.

Antoinette G. van Zelm is the assistant director of the Center for Historic Preservation at Middle Tennessee State University.