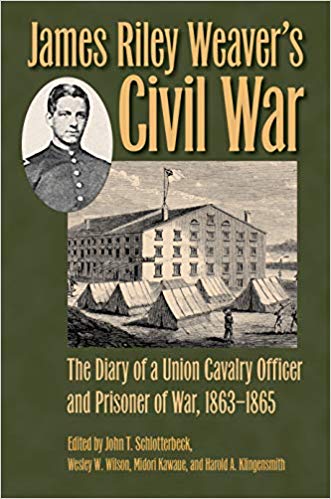

James Riley Weaver’s Civil War: The Diary of a Union Cavalry Officer and Prisoner of War, 1863-1865 edited by John T. Schlotterbeck, Wesley W. Wilson, Midori Kawaue, and Harold A. Klingensmith. Kent State University Press, 2019. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1-60635-368-4. $49.95.

James Riley Weaver’s Civil War: The Diary of a Union Cavalry Officer and Prisoner of War, 1863-1865 offers a new and unique perspective on the Civil War. James Riley Weaver, a Union officer in the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, spent almost seventeen months in seven Confederate officers’ prisons. From June 1, 1863, to April 1, 1865, Weaver detailed his experiences during the war. Scholars of the Civil War have long recognized the challenges of analyzing soldiers’ and prisoners’ personal narratives of the war—some memoirs were written years after the war, and some accounts written during the war focused exclusively on dramatic events. Memoirs published after the war by former Confederate and Union soldiers who spent time as prisoners of war often focused on sensationalizing the experiences within enemy prisons and vilifying captors. However, Weaver’s account as a prisoner of war differs from these dramatized accounts due to the fact that he wrote his diary during the war, rather than as a memoir in later years when his memories might have been skewed. His unbroken, 666-day record focused on daily observations rather than sensational stories, and he rarely relied on romanticized language to describe his conditions. Weaver’s writings provide rare insight into the complexities of the prisoner of war experience.

James Riley Weaver’s Civil War: The Diary of a Union Cavalry Officer and Prisoner of War, 1863-1865 offers a new and unique perspective on the Civil War. James Riley Weaver, a Union officer in the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, spent almost seventeen months in seven Confederate officers’ prisons. From June 1, 1863, to April 1, 1865, Weaver detailed his experiences during the war. Scholars of the Civil War have long recognized the challenges of analyzing soldiers’ and prisoners’ personal narratives of the war—some memoirs were written years after the war, and some accounts written during the war focused exclusively on dramatic events. Memoirs published after the war by former Confederate and Union soldiers who spent time as prisoners of war often focused on sensationalizing the experiences within enemy prisons and vilifying captors. However, Weaver’s account as a prisoner of war differs from these dramatized accounts due to the fact that he wrote his diary during the war, rather than as a memoir in later years when his memories might have been skewed. His unbroken, 666-day record focused on daily observations rather than sensational stories, and he rarely relied on romanticized language to describe his conditions. Weaver’s writings provide rare insight into the complexities of the prisoner of war experience.

Weaver never intended to publish his diary. He eventually published a reflection on his time in Libby Prison in 1899, “A Phi Psi’s Christmas in Libby,” which is included in the appendix of this book. Weaver’s descendants held onto the diary for generations, until they decided to make it available to DePauw University in 2011 under the condition that it would be transcribed and made available to the public. Editors John T. Schlotterbeck, Wesley W. Wilson, Midori Kawaue, and Harold A. Klingensmith worked collectively to transcribe Weaver’s writings, and to provide historical context for his diary. The editors also provide an introduction to the source material, a prologue to the beginning of the diary entries, short introductions to each chapter, and an epilogue that discusses Weaver’s postwar career and his work at DePauw University. These pieces of narration offer a greater sense of how Weaver’s story fits into the larger histories of the Civil War, and they also serve as excellent guides for understanding some of the key points within the diary entries.

Weaver’s incarceration began in October 1863 after a Battle at Brandy Station, in which he and thirty-one other men from the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry were captured by the 7th and 12th Virginia Infantry. Weaver and the other men were quickly taken to Libby Prison, where Weaver’s time as a prisoner in the “land of Secessia” began. (59) Weaver’s observations about Libby Prison confirm that conditions were harsh—there was unhealthy sanitation, furnishings were sparse, and the food varied in quantity and quality. Weaver notes mistreatment from Confederates from time to time, but he spends more time discussing news of the war than the guards within the prison. Weaver describes Libby as, “a little world in itself,” filled with men from “every class of society, high and low, rich, and poor, and from every country and clime.” (81) This description is fitting of the ways in which Weaver discussed all of the prisons and prison camps he resided in—each was its own little world that Weaver was able to observe, and as Weaver wrote his thoughts on the war continued to develop.

Weaver noted important events in his writings. For example, he discusses the Great Libby Prison Escape, but he admitted that he had been ignorant of any plans of the tunnel or an escape, and thus he went back to his daily life in prison after the event ended. Many of Weaver’s observations of important events during the war are similar in this respect; Weaver often made notes on events, detailed his thoughts on the matter, and then moved on. However, as the editors note, Weaver’s diary entries became longer and more reflective after he reached the one-year anniversary of his incarceration. Weaver admitted that the war had taught him to appreciate peace, and as Lincoln’s bid for re-election loomed closer, Weaver became anxious for the future. The day before the election he wrote, “Our Government will be established anew or the Confederacy will be a success.” (166) Such reflections demonstrate how Weaver’s time in prison made him contemplate the larger impact of the war on the United States.

Weaver’s diary provides new insights into the Civil War. His diary details numerous issues that will be fascinating to those interested in Civil War prisons—prison conditions, prisoner exchanges, attempts to escape, the emotional and mental challenges of imprisonment, and the daily life of a prisoner of war. Beyond imprisonment, Weaver’s early entries capture details of the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry’s battles, and his later entries continue to discuss the war in a larger scope. Ultimately, James Riley Weaver’s Civil War: The Diary of a Union Cavalry Officer and Prisoner of War, 1863-1865 offers new stories and a new perspective on the Civil War from a source that has been largely unread until now.

Carolyn Levy is a Ph.D. candidate in History & Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at The Pennsylvania State University.