Library of Congress

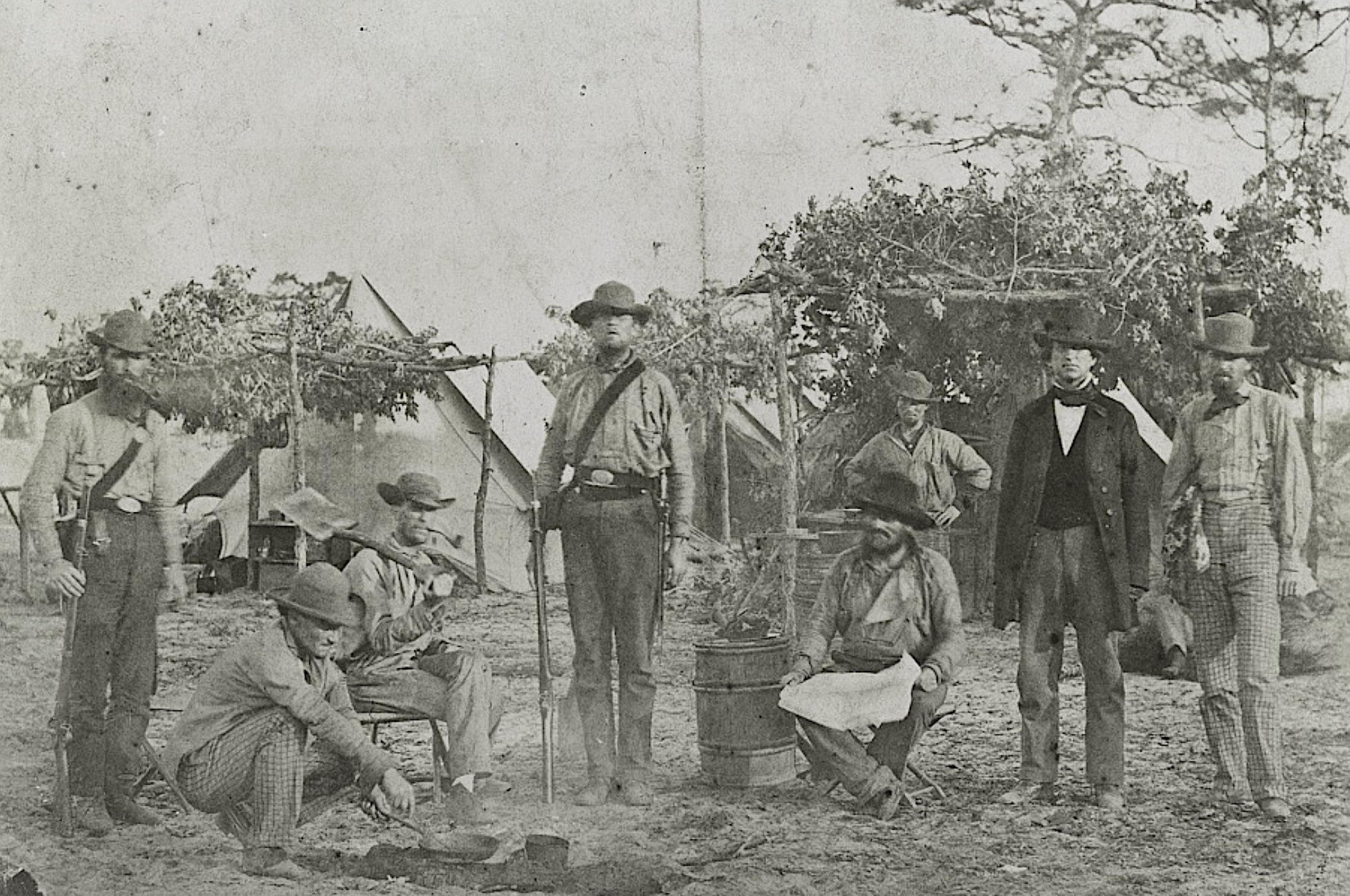

Library of CongressConfederate soldiers in camp at Pensacola, Florida, in 1861.

In the Voices section of our Summer 2025 issue we highlighted quotes by Confederate soldiers and civilians that reflect their intense feelings about their Yankee opponents. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“The invaders are at our gates and they must be repelled.”

—Louisiana officer Charles D. Dreux, in a letter to his wife shortly after arriving in Virginia, June 18, 1861. Weeks later, Dreux was killed in a skirmish with Union troops.

“The published accounts of the actings and doings of Lincoln’s army of clouts and scavengers … have filled the cup of indignation to overflowing and terrible will be the vengeance dealt out to them…. That day … is rapidly approaching.”

—A soldier in the 3rd Alabama Infantry, in a letter to the Georgia newspaper Columbus Sun, on reports of enemy activity in Alexandria, Virginia, June 1, 1861

“All of us … pay their wounded, as much attention as our own, for suffering knows no distinction of caste, kindred or condition; and Christian charity, under such circumstances, should make none.”

—Confederate surgeon Thomas A. Means, in a letter to his father about treating men wounded at the Battle of Bull Run, July 25, 1861

“We are still under the reign of terror…. This war is not one for the maintenance and perpetuity of the Union … but one for … the utter overthrow of the South and the extinction of slavery. But thanks to God … their pet schemes of conquests … received a glorious check in the salutary lesson taught them at Bull’s Run….”

—A pro-Confederate resident of Washington, D.C., in a letter to the newspaper Atlanta Southern Confederacy, July 30, 1861

“[It] is infested by numbers of faro dealers, many of whom have joined the army as privates for the purpose of swindling the poor soldier out of his hard-earned pittance of $11 per month.”

—A private in the 6th Alabama Infantry, on rumors about the Army of the Potomac, in a letter to the Georgia newspaper Columbus Sun, August 4, 1861

“The men are generally a fine, able-bodied set. Some appear, even yet, entirely ignorant of the result of the conflict in which they were engaged, and lament the personal misfortune to themselves, that they are prisoners, when their army won the battle! Others acknowledge their defeat, and regret the errand upon which they entered, while others, again, assume a bold, defiant, and even insolent tone, saying that if released they ‘would do the same thing over again.’ This number is small.”

—A soldier in the 20th Georgia Infantry, on his impression of Union soldiers taken prisoner at the Battle of Bull Run, in a letter to the Columbus Sun, August 5, 1861

“Near one of the dead Yankees I found a letter, written the day before the battle, addressed to his sweet heart, and telling her that he was about to start for Richmond—that there would be a slight battle at Manassas, where they would gain the victory, and in two more days would breakfast in Richmond. Poor girl! If she loved him, it will grieve her heart to hear how his high hopes melted away, when Southern prowess turned the tide of invasion at Manassas. Some of the Yankees, however, were pretty saucy, and said that we had done no thing great in killing a few men and taking a few cannon—that there was plenty of the same sort left where they came from.”

—Captain William H. Mitchell, 11th Georgia Infantry, in a letter to a friend in the wake of the Battle of Bull Run, August 11, 1861

Library of Congress

Library of CongressUnion officer Michael Corcoran

“I was introduced to Col. Corcoran…. He is doubtless a brave man and fought on the memorable 21st, for what he deemed principle and the respect he owed ‘the stars and stripes.’ Misguided being! It is a pity that his talent and courage had not been exerted in a better cause.”

—A soldier in the 15th Alabama Infantry, on meeting Michael Corcoran, colonel of the 69th New York Infantry, during a visit to a Richmond prison holding Union prisoners taken at the Battle of Bull Run, August 31, 1861. Corcoran, a native of Ireland who had played a key role in convincing fellow Irishmen to enlist in the Union army, would rise to the rank of brigadier general after his release.

“A church in this place is now used for a hospital. At one door lies a man wounded in the left leg, as he says, by a cannon ball, in the battle of Manassas…. Yesterday, with some friends, I visited him. We asked what state he was from. He replied, ‘from the United States.’ In speaking of his condition, he only regretted that he was not killed instead of being wounded. We told him that he would soon be well and could get an opportunity of having his desires accomplished.”

—A soldier in the 15th Georgia Infantry, in a letter to an Atlanta newspaper, September 24, 1861

“[General George] McClellan has made many excuses for not giving us a fight. Now I suppose it is cold weather. Ah! Yes; Mr. Yank is accustomed to quartering in warm houses in the winter and can’t expose himself to snow, though he ventures out occasionally to search for food for his starved horses, when our bold cavalry then dart out, pounce on him, and bring him … to Richmond where he has been desiring to go, … but not exactly in that style.”

—A soldier in the 8th Georgia Infantry, in a letter to a newspaper from his home state, December 3, 1861

“In nearly every battle they claimed a victory. Every letter to the New York press bore the lie upon the face of it. They are a nation of liars—unblushing, God-forsaken liars—and every effort to conceal the disaster to McClellan’s army only stamps them as liars.”

—Virgil A.S. Parks, 17th Georgia Infantry, in a letter to the Savannah Republican about the northern reaction to the recent defeat of George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac at the Seven Days Battles, July 11, 1862

“[I]t is best always not to underrate an enemy, and then every energy will be employed to meet him. Rather overrate than underrate him.”

—A letter from a soldier in the 2nd Georgia Infantry to a Savannah newspaper, July 31, 1862

“The Yankees fought like Devils.”

—A soldier in the 15th Alabama Infantry, on the Battle of Antietam, in a private letter published in the Georgia newspaper Columbus Sun, September 25, 1862

“Many of her butchers sleep now within sight of the smoke of her burning dwellings—their only anthem shall be the curses of an oppressed people. Like thieves they came and like dogs are they buried, their epitaphs shall not be written nor marked their graves, for their deeds have proven them unfit for place in Heaven or on earth.”

—A soldier in the 8th Georgia Infantry, on the battlefield graves of Union soldiers killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg, in a letter to an Atlanta newspaper, January 7, 1863

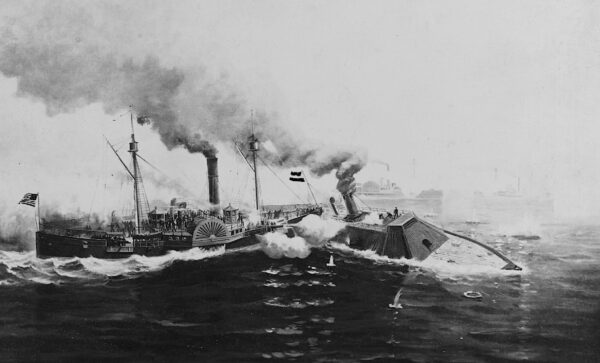

The New York Public Library

The New York Public LibraryThe Battle of Fredericksburg, as depicted by artist Thure de Thulstrup.

“We remain in status quo, facing the ‘nigger stealers,’ with nothing to vary the monotony of camp life, except the advent of the holidays.”

—A soldier in the Army of Northern Virginia in a letter to an Atlanta newspaper, January 9, 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation had gone into effect on January 1.

“Many a Yankee … is trembling now over the gloomy way to death which is so elegantly spread out before them.… The dread reality that these places must fall by storming terrible earthworks (which Yankees have never yet accomplished) with rebels behind them, has bread a perfect harvest of horror about Yankee gizzards.”

—A Confederate soldier based in Richmond, reflecting on the Union attempt to take Charleston and Savannah, in a letter dated March 10, 1863

“[T]he dead bodies of Yankees could be seen all around. Some had fallen at their guns—others had been killed on their way to the rear; some lying badly wounded, and the groans of the wounded and dying, though I hated the cause for which they fell, grated harshly on my ears, whilst I felt deep commiseration for the poor deluded victims of an abolition fanaticism.”

—John H. Bogart, 61st Virginia Infantry, in a letter about the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 8, 1863

“No doubt it was a purpose of showing southern generosity to a fallen foe, but the character of this foe was certainly not understood by them. The brave may be merciful to a dog, but there is little use of showing honors to such, because honors are lost on it. We cannot believe our women—the women of the South—could neglect those who are in the field to cultivate the favor of such off-cast wretches….”

—A Confederate soldier from Georgia, reacting to reports of the kind treatment Union soldiers received while passing through Atlanta and Augusta, in a letter to the Savannah Republican, May 24, 1863

“I think I made quite an impression on one young lady. She was exceedingly obliging in the way of bread, butter, milk, and complimentary remarks, which later, I returned to the best of my ability. I have no doubt that I could have made a rebel of her if I had tried. She was altogether the best looking girl I saw, but I would not consider her good looking out of Pennsylvania.”

—A Confederate soldier on a civilian he encountered on his march to Gettysburg, in a letter to an Alabama newspaper, July 18, 1863

“What a pleasant contrast is there presented between the Federal and Confederate soldier. The one a foreign mercenary on an errand of plunder, with no higher idea of liberty than the license to satiate a vitiated appetite, and gratify a corrupt lustful nature. The other, called to the field by a sense of honor and the higher obligation of duty, leaves all he holds dear and bares the bosom to the dangers of the battle field willingly, rather than to see his home despoiled by a brutal foe without honor or mercy.”

—A Confederate soldier, in a letter to the Augusta Weekly Chronicle & Sentinel, September 9, 1863

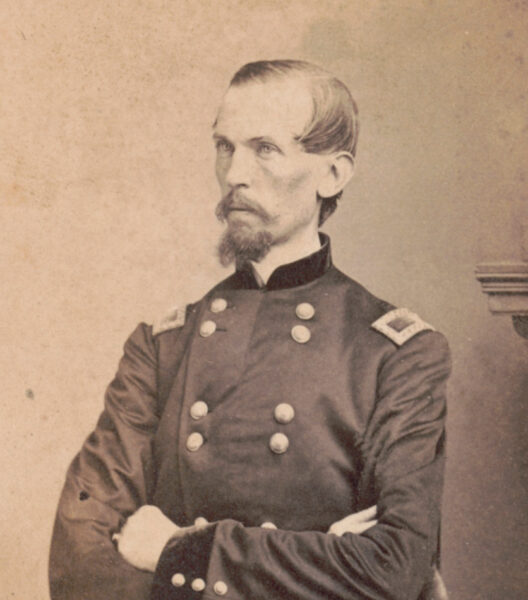

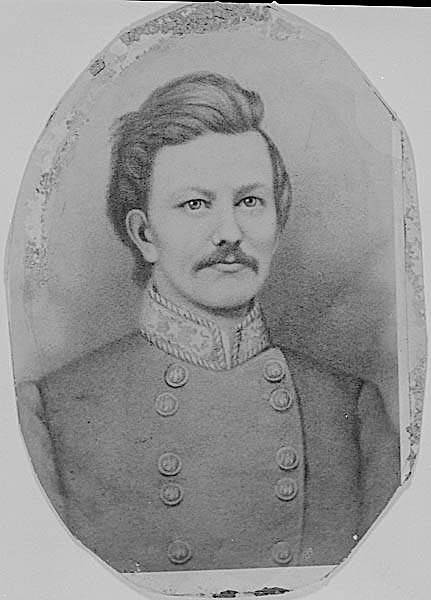

Small Print Collection, RG 48-2-1, Georgia Archives

Small Print Collection, RG 48-2-1, Georgia ArchivesConfederate colonel Clement A. Evans

“The mercenary hirelings of the Yankee army continue their inglorious, but merciless and barbarous warfare against ourselves, our homes, and our families, only for pay of hundreds of dollars in bounties and the sordid hope of future plunder.”

—Colonel Clement A. Evans, in a circular issued to the men of his brigade, February 4, 1864. Evans told his men that their motivation, by contrast, was “the delightful consciousness of doing right … without conscription or bribe.”

“If you ever want to see your son put up one of your old fashion Bull Dog fights just let him come in contact with a negro Regiment…. I intend to fight them until I am as bloody as a Butcher.”

—Virginia soldier William H. Phillips, in a letter to his parents on the prospect of facing black Union soldiers in battle, January 15, 1864

“[T]he men were perfectly exasperated at the idea of negroes opposed to them & rushed at them like so many devils.”

—North Carolina soldier Thomas R. Roulhac, in a letter to his mother about a battle at Suffolk, Virginia, where black Union soldiers were killed after surrendering, March 13, 1864

“The scum of the North cannot face the chivalric spirit of the South.”

—Confederate officer Henry Ewing, in a letter to a friend, May 1, 1861

“Not a hoof should be left behind, not a grain unconsumed, not a factory, bridge, or rail road undestroyed—thus and thus only can we teach our uncivilized opponents a just appreciation of our rights and of the rules of war.”

—Confederate soldier R.H. Simpson, in a letter home about his wishes for Robert E. Lee’s planned campaign into Pennsylvania, June 22, 1863

“They have been living as if no war existed in America…. It is just that they should feel the war: all persons South with few exceptions have suffered.”

—Alabama officer Elias Davis, in a letter to his wife during the early days of Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania, June 27, 1863

“The Yankees are like ferocious monkeys.”

—Alexander Cheves Haskell, 1st South Carolina Infantry, outlining his perception of the enemy at war’s outset in a letter to his mother, May 4, 1861

“I certainly love to live to hate the base usurping vandals, if it is a Sin to hate them, then I am guilty of the unpardonable one.”

—Confederate soldier H.C. Kendricks, on his feelings toward Union soldiers, in a letter home written in early 1863

“[T]he cold-hearted Yankees … [are] fit descendants of the intolerant and murderous race who first landed at Plymouth rock.”

—Andrew DeVilbiss, 11th Louisiana Infantry, in a letter home, October 14, 1861

“[T]he Yankey army is now as good as ours.”

—Shepherd Green Pryor, 12th Georgia, in a letter to his wife after the Battle of Antietam, October 3, 1862

“[S]ince I have seen how well people live without Negras I am tempted to wish I never had one. I seen something of private life in a free State while in Penn.”

—Mississippi soldier Jerome B. Yates, in a letter home after the conclusion of the Gettysburg Campaign, August 14, 1863

“Teach my children to hate them with that bitter hatred that will never permit them to meet under any circumstances without seeking to destroy each other. I know the breach is now wide & deep between us & the Yankees let it widen & deepen until all Yankees or no Yankees are to live in the South.”

—Georgia soldier T.W. Montfort, in a letter to his wife, March 18, 1862

“I would send you a sample of them, but I am ashamed they are so vulgar…. I do not believe God will ever suffer us to be subjugated by such a motly crew of infidels.”

—Confederate soldier John Crittenden, in a letter to his wife about Union soldiers’ letters he had found and read during the Atlanta Campaign, May 29, 1864

“Poor fools…. [T]he Yankees treated them so badly, they thought we would do the same. They soon found out that there is a great difference. The Yankee army is filled up with the scum of creation and ours with the best blood of the grand old Southland.”

—Confederate soldier George W. Jones, on the civilian reaction to him and his comrades in Braxton Bragg’s army during their march through Kentucky, in his diary, September 10, 1862

Sources

Writing and Fighting from the Army of Northern Virginia ed. by William B. Styple (2003); Randall C. Jimerson, The Private Civil War (1988); Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb (1943).