Union soldier Francis M. Ingram “did not enjoy the 6 of April as well as I hav enjoyed some Sundays.”[2] On the banks of the Tennessee River, the “Rebel tide … was coming in like a wave of the sea unresisted and irresistible.” Around 65,000 Federal troops faced off against 45,000 Confederates under the command of General Albert Sidney Johnston. “Here we were a new Regt which had never until this morning heard an enemies gun fire[,] thrown into this hell of battle—without warning,” recalled Sergeant Cyrus F. Boyd of the 15th Iowa Infantry. Amid the dense smoke and spray of bullets, companies in the heat of battle “became all mixed up and without organization.” Boyd watched the lush vegetation “cut down as if a mowing machine had gone through the field and limbs fell like autumn leaves in the leaden and iron storm.” Men, too, were mowed down, and “acres of dead and wounded told the fearful tale of sacrifice.” As dusk fell, the moans and wails of the dead and dying punctuated the bloody hellscape.[3]

For many young men, the Battle of Shiloh was their first taste of combat, and the experience rarely lived up to their expectations. The 22-year-old Ingram admitted, “well darn the fight … it aint the thing it is cracked up to be.” He told a friend, “I hav see the monkey dance.” Others would remember April 6, 1862, as the fateful day where they first “saw the elephant.”[4]

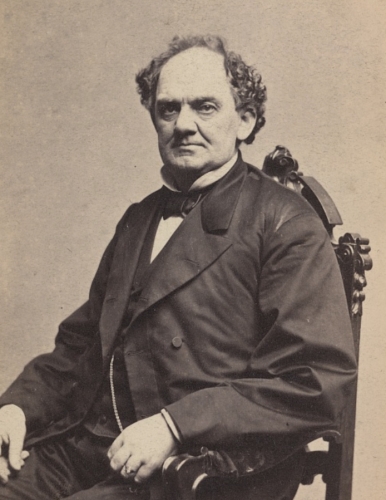

P.T. Barnum

In early America, the circus was a rare treat. In May 1808, Americans had the opportunity to visit “a living elephant” at the Washington Tavern in Richmond, Virginia. According to the newspaper, “this generation may never have the opportunity of seeing the elephant again, as this is the only one in the United States.” Traveling menageries grew in popularity as show business prospered. In 1850, agents of circus pioneer P.T. Barnum traveled to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and captured “thirteen elephant of a suitable size for their purpose, with a female and her calf, or ‘baby’ elephant, only six months old.” Upon their return to New York, Barnum added tents, carriages, horses, “a caravan of wild animals,” and General Tom Thumb, a dwarf. Barnum’s Great Asiatic Caravan, Museum, and Menagerie toured for four years, grossing nearly $1 million.[5] By midcentury, customers North and South could see the elephant for mere pennies.[6] Yankee Notions, a satirical publication, reported on Barnum’s Fourth of July show in Springfield, Massachusetts. An eager visitor had set off to see the elephant, but his expectations were not met. “Before I got in town,” he lamented, “they’d got all through the paradin’, the elephants was unharnessed, and the Car of Jugglenot was backed into a woodshed. I made up my mind right off, then, that the hull consarn was humbug.”[7]

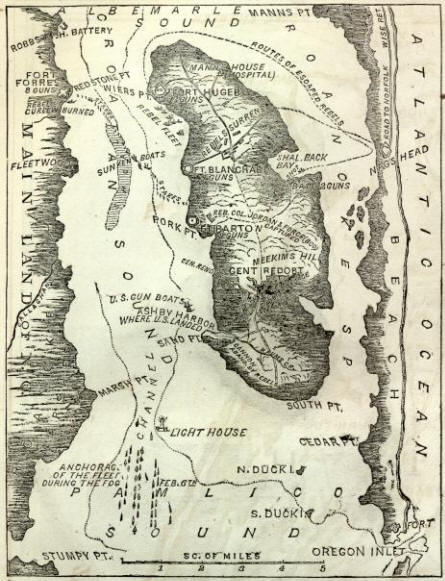

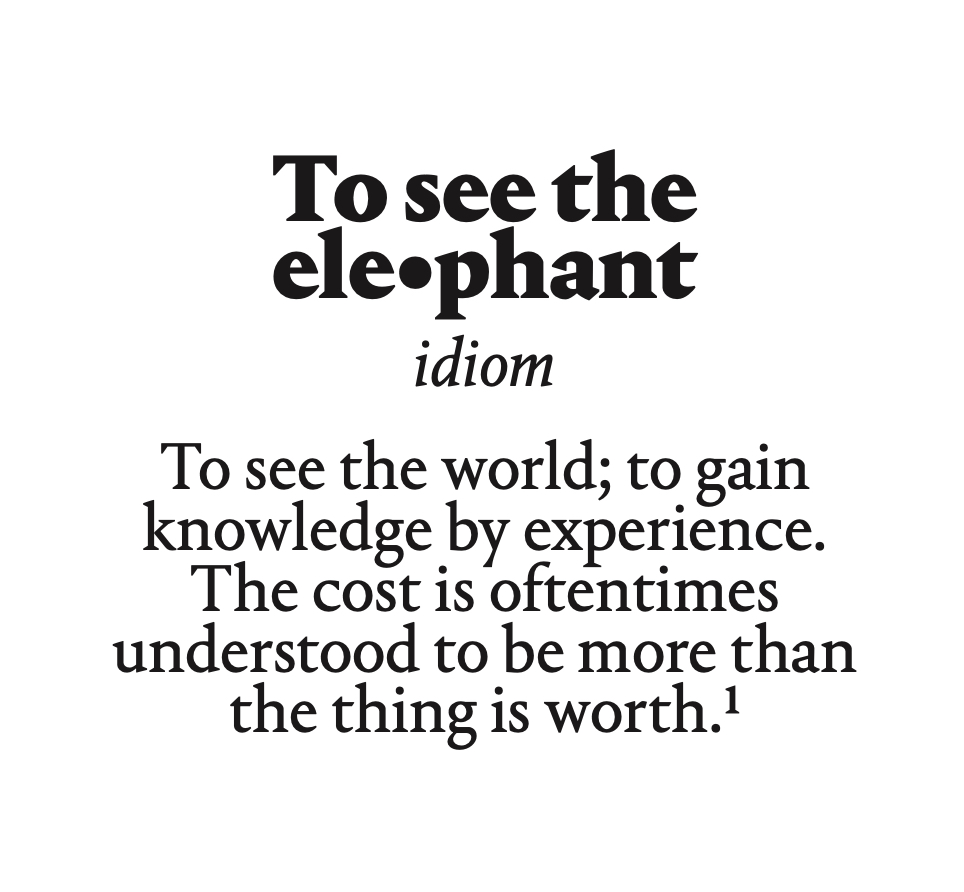

While circus performances were generally associated with the Northeast, the phrase seeing the elephant originated in the Southwest in the 1840s. Young men went west in droves in the 1840s and 1850s, and for many of them the impressive landscape alone conjured notions of militant manhood, rugged individualism, and white independence. While accompanying the 1841 Texan Santa Fe Expedition, journalist George Wilkins Kendall first heard the phrase spoken by an “old campaigner” in Cross Timbers, Texas. “I had already seen ‘sights’ of almost every kind, animals of almost every species … and I felt ready and willing to believe almost anything I might hear as to what I was yet to see; but I knew very well that we were not in an elephant range, and when I first heard one of our men say that he had seen the animal in question, I was utterly at a loss to fathom his meaning,” Kendall wrote. After a round of laughter at the newcomers’ confusion, someone explained the expression’s meaning: “When a man is disappointed in anything he undertakes, when he has seen enough, when he gets sick and tired of any job he may have set about himself, he has ‘seen the elephant.’” This is one of the first recorded uses of the idiom in print.[8]

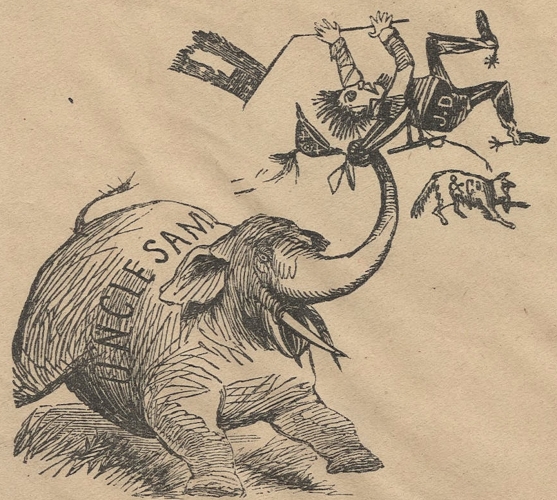

In this illustration from a wartime envelope, Confederate president Jefferson Davis “sees the elephant” in the form of a pachyderm labeled “Uncle Sam.”

The Mexican War popularized the expression, and soldiers began to associate seeing the elephant with military service. The romance of the West and the excitement of a soldier’s life quickly dissipated in the face of military reality. “If you think this a romantic spot, or that there is poetry connected with our situation,” cautioned an Indiana volunteer, “you need only imagine us trudging through a swamp, lugging our moldy crackers and fat bacon … to become convinced that this is not a visionary abode.” After crossing the desert along the lower Colorado River, an army surgeon wrote home, “I have seen the Elephant and I hope I shall never be compelled to cross it again.” For American soldiers in the Southwest, “the elephant” assumed various forms: arid landscapes, rough river crossings, boredom in camp, sickness, and military combat. One newspaper correspondent in Matamoros described his dispatches as “the features of the elephant.”[9]

By midcentury, this southwestern expression was in common usage across the United States. John Russell Bartlett’s 1848 Dictionary of Americanisms first defined the term and specifically linked the idiom to Mexican War service. “For instance, men who have volunteered for the Mexican war, expecting to reap lots of glory and enjoyment, but instead have found only sickness, fatigue, privations, and suffering, are currently said to have ‘seen the elephant.’”[10] The war had broadened the meaning of the phrase to encompass terror and fright as well as disappointment and hardship—all common aspects of camp and combat.

Not many years later, thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers saw the elephant for themselves. These men anticipated their first battle with a mixture of intrigue and dread. Would they live up to Victorian-era expectations and prove themselves honorable men and courageous soldiers? Confederate private Andrew J. White wrote to his wife in Georgia of his to desire to see “you and all the childering be fore I went becaus we are Shore to see the Elephant this time I thi[n]k.”[11] Thomas Murray of the 20th Iowa Infantry, meanwhile, thought battle transformed men for the better and urged his cousin to “try and get him to come to war I think that would take a little of the dandy out of him If he was down here in the rear of Vicksburg I think he would see the Elephant.”[12] Civil War combat spawned other idioms: saw the monkey dance and saw the monkey show. Synonymous with seeing the elephant, these circus-inspired expressions gave voice to the disappointing yet horrifying experience of combat. These idioms mostly fell out of favor in the succeeding decades, and soldiers in the next century’s world wars rarely referred to seeing the elephant. Today, the expression has become almost exclusively linked to Civil War-era combat and few remember its origins during the era of circus show business and westward expansion.

TRACY L. BARNETT IS A DOCTORAL CANDIDATE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA. HER DISSERTATION ANALYZES THE HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF AMERICA’S GUN CULTURE AND ITS MUTUALLY CONSTITUTIVE RELATIONSHIP TO WHITE SUPREMACIST IDEOLOGY. AS THE DIGITAL HUMANITIES RESEARCH FELLOW, SHE WORKED AS A RESEARCH ASSISTANT FOR PRIVATE VOICES, A WEBSITE DEVOTED TO CIVIL WAR LANGUAGE.

This article appeared in the Winter 2021 issue (Vol. 11, No 4) of The Civil War Monitor.