SCAL•A•WAG | noun | A word signifying a low, worthless fellow. During the reconstruction period following the Civil War, it was at the South applied to Southerners who joined the Republican party and aided them in the reconstruction.1

Harper's Weekly

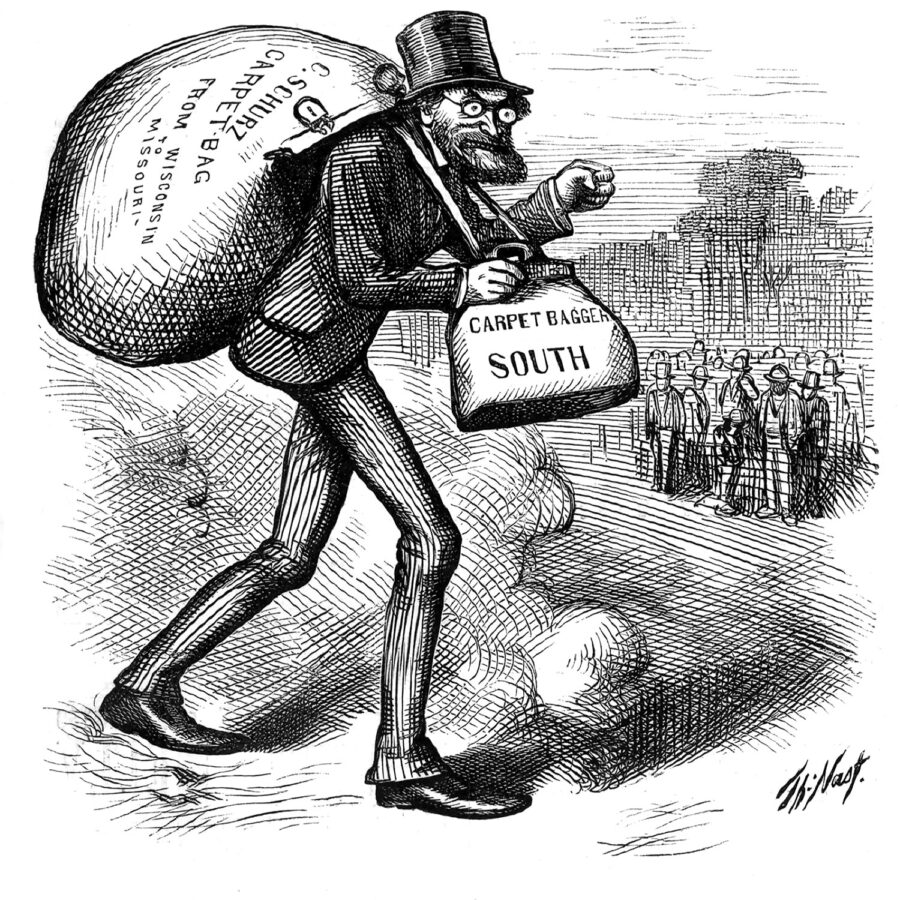

Harper's WeeklyThe term “scalawag,” used before and during the War to describe undesirable creatures—from animals to people—came to be associated during Reconstruction with white Southerners who supported the Republican Party. After 1868, the Southern press and public generally used “scalawag” and the term “carpetbagger”— applied to white Northerners who moved to the south during Reconstruction—interchangeably. shown here: Thomas Nast’s depiction of a “carpetbagger” in the November 9, 1872, issue of Harper’s Weekly.

The term Scalawag entered American parlance in the early 1800s. Its origins can probably be traced to 17th-century Scotland, where farmers sold their inferior livestock at markets in Scalloway, once the capital of the Shetland Islands northeast of the mainland. The Gaelic speaking residents of the Hebrides, the archipelago northwest of the mainland, used scallag to denote a person without stature or a drifter who performed menial tasks. Scotch-Irish immigrants probably brought the term with them to the United States.2 Both the spelling and meaning varied considerably in the Early American Republic. In an agricultural context, it referred to poor-quality farm animals selling at low prices; according to a late 19th-century Virginia newspaper, the term “applied to all of the mean, lean, mangy, hidebound skiny, worthless cattle in every particular drove.”3 It also functioned as a popular slur, hurled in fights, political squabbles, and business disagreements. In one of the term’s first appearances in print, an Ohio newspaper reported in 1839 on the presence of one Judge Lynch, who “remained here long enough to give a worthless scalawag a genteel suit, from ‘head to heels’ of tar and feathers.”4 Published in 1848, the first edition of John Russell Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms defined scallawag as “a favorite epithet in western New York for a mean fellow; a scape-grace.”5 In the 1850s, newspapers across the United States, but especially in the Midwest, referred to unscrupulous politicians, petty thieves, fraudulent currency, and undesirable cattle as scalawags.6

By 1861, Americans were familiar with the term and Union and Confederate soldiers occasionally employed it to insult their comrades and commanders. Bounty jumpers, hospital attendants, and cowards, in particular, often found the term applied to them. Proposing a new cash bounty system to spur military enlistment, federal and state supporters claimed the payments benefited the destitute families of soldiers, encouraged volunteerism, and prevented harsher conscription policies. An opponent, meanwhile,“ thought that none but scalawags” would sign up for the bounty and “he wanted a draft to bring the proper persons into the service, they will not go for a bounty, they should be drafted.” After considerable debate in Scott County, Iowa, the Board of Supervisors adopted the bounty to incentivize enlistment, paying $75 to married men and $50 to single men.7 In Annapolis, Maryland, a Union soldier claimed that “more than two-thirds of the hirelings styled nurses and servants … were cowards and skulkers of the vilest order, who ran away from their comrades in the day of battle.”8 The ambulance crew facilitated the removal of battlefield wounded, but “officers and men of doubtful courage used every exertion to be detailed for this service, because they considered it a safe position.” When requested to detail 10 soldiers for ambulance duty, it was reported that a Union commander refused, saying “take the most worthless cowards and stragglers that you have got; I won’t insult my good and brave men by sending them to such a lot of scalawags.”9

In 1864 and 1865, scalawags lacked a fixed political identity, and the term functioned as an insult for either abolitionist Republicans or anti-war Democrats. Northerners in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa lobbed slurs against their political adversaries during the contentious 1864 campaign between incumbent President Abraham Lincoln and his challenger, Democrat George B. McClellan. In these agricultural communities, many Democrats and recent immigrants opposed emancipation and instead advocated for the immediate end of wartime hostilities. In August 1864, James Trimble, a political activist from Tennessee, traveled throughout Ohio on behalf of Lincoln, making “speeches wherever he goes, denouncing Democrats as ‘Copperheads’ and stigmatizing them as ‘secession sympathizers.’” Inciting local Democrats, The Daily Ohio Statesman declared Trimble an “Abolition Scallaway” and a “Humbug and a Bore.”10 More often than not, Republicans considered anti-war northern Democrats to be Copperheads, but some were occasionally labeled scalawags. In central Iowa, the Charles City Intelligencer reported “the worst set of scalawags ever known in that country have taken up their abode” since the 1864 presidential election. Offering a physical description of the offending parties, the story continued, “They have bogs on their feet, wool in their eyes…. Owing to the scarcity of cheap whiskey, they have very sour stomachs. They smoke copper pipes and are said to be fixing themselves up with butternut uniforms.”11

After the war, the federal government began the decades-long process of reconstructing the South and reckoning with the effects of emancipation. Radical Republicans in Congress openly clashed with Lincoln’s successor, President Andrew Johnson, a former Democrat from Tennessee who envisioned a lenient reunion that preserved the legacy and vestiges of white supremacy. Within the contentious political environment of 1865 and 1866, the southern press vilified native-born southern Republicans, calling them “southern loyalists,” “southern renegades,” “mean native whites,” “Judas Iscariots,” and “southern white simon-pure loyalists.”12 Several thousand white northerners, many of them from mid-Atlantic and New England states, packed their personal effects in black valises, or carpetbags, and moved South during and immediately after the war. Seeking political office, career advancement, and business opportunities, these Union veterans, Freedmen’s Bureau agents, schoolteachers, and other northerners purchased former plantations and opened businesses across the South, most retaining their political affiliation as Republicans.

In March 1867, Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act, which divided the former Confederacy into five military districts and outlined the process for southern states to be readmitted to the Union. In addition to ratifying the 14th Amendment, each state was required to rewrite its state constitution and have it approved by the majority of voters, including newly enfranchised black men. In 1867 and 1868, white and black delegates formed state conventions and assembled in capital cities across the South. From November 5 to December 6, 1867, delegates gathered in Montgomery, Alabama, and journalists covered the proceedings of the “Black and Tan” convention—as the black and white delegates were mockingly described—with intense interest.13 Montgomery’s Daily Mail, led by Joseph Hodgson from Virginia, claimed that delegate Charles A. Miller “does not even pretend to deposit his black carpet-sack in Lowndes County.” Investigating Miller’s origins, the newspaper claimed to “have made diligent inquiry as to his antecedents … but the invariable response is ‘Don’t know him!’ ‘Think he is from Ohio!’—‘Believe he is from Maine!’ ‘May be he is from Russian America!’”14 The Daily Mail christened other northern delegates as “carpet bag gentry,” “carpet bag Bureau man,” and “carpet bag fellow.”15 On February 13, 1868, a New York newspaper adopted the term: A “good deal of bitterness of feeling has been shown in all the conventions in regard to the presence and great prominence as members, of what the Louisiana people call ‘carpet-baggers’—men, that is, who are new-comers in the country.”16 The epithet stuck, and by early 1868, white northerners who had moved South were known nationwide as carpetbaggers.

In mid-1867 another slur entered into the Reconstruction era discourse: scalawags. Initially a catchall term for northern and southern-born Republicans, a newspaper from Columbus, South Carolina, professed to prefer black political leadership to “the scallawags, great and small, native and imported.”17 The meaning of the term was refined later that year, when the Chronicle and Sentinel, based in Augusta, Georgia, applied the term exclusively to white southern Republicans.18 According to W.C. Elm’s 1871 biographical sketch, “‘Scalawags’ are verminous, shabby, scabby, scrubby, scurvy cattle. Therefore there is a manifest fitness in calling the native Southerner, of white complexion, who adopts the politics of the Radical party, a Scalawag. It is not so much because he is for negro equality and all that stuff, that he is and should be called a Scalawag, but because he renounced all his previous professions and practices, slinks from his own color and kindred, and foregathers with dirt freemen, to gain whose favor and votes he maligns all respectable citizens and incites the colored rabble to all sorts of absurd pretensions, or worse, to deeds of violence and blood.”19 After 1868, the southern press and the general public often used carpetbagger and scalawag in tandem. According to a black preacher, “A carpet-bagger came down here from some place and stole enough to fill his carpet-bag, but the scalawag was a man who knew the woods and swamps better than the carpet-bagger did, and he stole the carpet-bagger’s carpet-bag and ran off with it.”20

According to historian James Alex Baggett’s statistical study, the majority of scalawags were lawyers, teachers, and urban professionals, and approximately one-third had been born abroad or outside the slaveholding South. In the upper South, they were former Whigs; in the southwest, they had previously lent their support to Stephen A. Douglas’ wing of the Democratic Party. In 1860 and 1861, they had opposed secession, supporting the preservation of the Union. Some, but not all, had fought in the Confederate army, and most formally joined the Republican Party only after the end of the Civil War.21

Most white southerners vilified the scalawags in their midst and subjected them to social exclusion and sometimes physical violence. Georgia’s Rome Tri-Weekly Courier supported Democrats’ attempts “to prosecute the good work until there shall not be a carpet-bag or scalawag office-holder in the State. We intend to drive them from power as we would a band of marauders seeking to despoil the ‘Empire State of the South’ of her honor and her treasures.”22 White supremacist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan targeted black voters and, to a lesser extent, white southern Republicans. In Hamburg, South Carolina, a white supremacist group attacked the majority-black town in July 1876—an event known as the Hamburg Massacre—during the leadup to elections. Louis Schiller, a former Confederate cavalryman and the town printer, “tried to help” black voters “as much as I could, in regard to governing themselves, [and have] been a leader among the republican party.” In response, white Democrats refused to recognize him socially and, during the violence, threatened to kill his wife and children.

Testifying before the U.S. Senate, Schiller said, “I was what they called a scalawag. I have been in the republican party since 1868.”23 A white Louisianan succinctly summarized the plight of white southern Republicans during Reconstruction: “being a scalawag places a man rather below par … politically.”24

Reconstruction mandates ended in 1877, leaving southern white Democrats to disenfranchise black men, terrorize Republican voters, and oust the scalawags and carpetbaggers from their political offices. In 1888, Everit Brown’s Dictionary of American Politics defined scalawag as “A word signifying a low, worthless fellow. During the reconstruction period following the Civil War, it was at the South applied to Southerners who joined the Republican party and aided them in the reconstruction.”25 While few southern Republicans remained in office during the 1880s and 1890s, the term had entered the American lexicon and would remain forever associated with the turbulent era of Reconstruction.

Tracy L. Barnett is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia. Her dissertation analyzes the historical origins of America’s gun culture and its relationship to white supremacist ideology. She teaches history at Loyola University Maryland.

Notes

1. Everit Brown, Dictionary of American Politics (Troy, NY, 1888), 461.

2. James Alex Baggett, Scalawags: Southern Dissenters in the Civil War and Reconstruction (Baton Rouge, 2003), 1–2.

3. Richmond Daily Enquirer and Examiner, June 13, 1868.

4. Maumee City Express (Maumee City, Ohio), August 3, 1839.

5. John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States, First Edition (New York, 1848), 284.

6. The Tipton Advertiser (Tipton, Iowa), October 8, 1859; Kenosha Telegraph (Kenosha, Wisconsin), October 11, 1850; The Republic (Washington, D.C.), September 8, 1852; Daily American Telegraph (Washington, D.C.), October 20, 1852; New York Herald, October 14, 1856.

7. Daily Democrat and News (Davenport, Iowa), August 15, 1862.

8. Henry Nichols Blake, Three Years in the Army of the Potomac (Boston, 1865), 300.

9. Ibid., 304–305.

10. Daily Ohio Statesman (Columbus, Ohio), August 4, 1864.

11. Charles City Intelligencer (Charles City, Iowa), December 8, 1864.

12. Ted Tunnell, “Creating ‘The Propaganda of History’: Southern Editors and the Origins of ‘Carpetbagger and Scalawag,’” Journal of Southern History, Vol. 72, No. 4 (November 2006): 802–803.

13. Ibid., 795–796.

14. Daily Mail (Montgomery, Alabama), September 28, 1867.

15. Ibid., November 12, 14, 19, December 3,1867.

16. The Nation, February 13, 1868.

17. Daily Sun (Columbus, South Carolina), September 7, 1867.

18. Tunnell, “Creating ‘The Propaganda of History,’” 792–793, 797, 801.

19. W.C. Elm, “A Scalawag,” The Southern Magazine, Vol. 8 (April 1871): 456.

20. House Misc. Doc, 42 Congress, 2 Session, No. 211, 478, as quoted in Ella Lonn, Reconstruction in Louisiana After 1868 (New York, 1918), 10.

21. Baggett, Scalawags, 261, 270.

22. Rome Tri-Weekly Courier (Rome, Georgia), February 25, 1874.

23. Testimony as to the Denial of Elective Franchise in South Carolina at the Elections of 1875 and 1876, Taken Under Resolution of the Senate December 5, 1876, Vol. 1 (Washington, 1877), 155.

24. Reports of Committees of the Senate of the United States for the Third Session of the Forty-Fifth Congress, 1878-1879, Vol. 1 (Washington, 1879), 264.

25. Brown, Dictionary of American Politics, 461.

Related topics: Reconstruction