Library of Congress

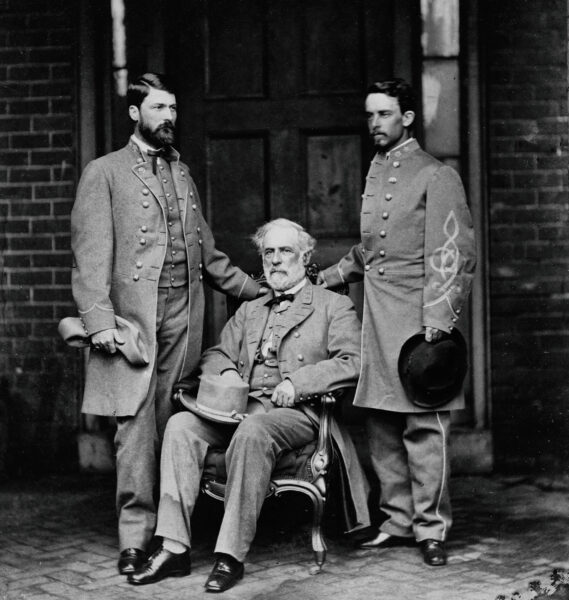

Library of CongressSanitary conditions—in particular the situating of latrines—were a vital and often overlooked consideration when arranging regimental camps. Shown here: The camp of the 66th New York Infantry at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1862.

For every one soldier killed in battle in the Civil War, two died of disease. The greatest killer was dysentery, a stomach infection that is usually spread by the improper handling of human waste. The most dangerous place in the bloodiest conflict in American history was not the battlefield, but the latrine.1 Military manuals from the period detail the proper layout of an encampment, including the construction and placement of latrines (or “sinks”). One might assume that these standards were implemented and enforced. But casualty lists and official orders issued during the war, along with the letters, diaries, and memoirs of participants, prove that the textbook military latrine was an aspiration rather than a reality. Many volunteer officers were ignorant of proper latrine discipline and rarely ordered the construction or maintenance of latrines as manuals outlined; soldiers proved reluctant to use latrines as well. These difficulties were compounded by a disturbing degree of institutional confusion. Officers often ordered the construction of sinks near or directly on bodies of fresh water—fueling epidemics of dysentery.

Many historians have argued that military discipline improved over the course of the war, detailing how the raw volunteers of 1861 became professional soldiers by 1865. But that development looks different viewed from the latrine. In terms of waste management, there was no linear improvement over time. Latrine discipline waxed and waned depending on a variety of factors. Indiscipline plagued the construction, maintenance, and use of the latrine throughout the conflict, and offers insight into how and why discipline broke down in Civil War armies. The latrine pitted military discipline against the anarchic, irrepressible calls of nature, illustrating how discipline worked—and didn’t work—in Civil War armies.2

To understand why the latrine failed, we need to understand how it was supposed to succeed. The latrine was only one apparatus in a larger system of discipline, surveillance, and sanitation. The 19th-century military camp was laid out in manuals as a model of circulation. Contemporary medical belief held that bad air (miasma) was one of the main causes of disease. Everyone from housewives to government officials sought to circulate fresh air as much as possible. Military manuals commanded that all forms of encampment be laid out to encourage rapid circulation of air, men, material, and refuse. Circulation promoted rapid response to external threats—both the enemy and disease.3

In this scheme, the malodorous latrine was placed as far from the camp as could be managed. Manuals stipulated that latrines were to be dug 300 paces to the front and rear of a camp. Guards were posted at the same distance. The latrine itself, as prescribed by manual and official order, was a 6-to-8-foot trench with a log or rail perched over the edge. Every evening a detail of soldiers covered the accumulated waste with six inches of earth. Once the latrine was filled, it was to be completely sealed, and a new latrine dug immediately. Latrines were understood to be vectors of disease due to their bad odors and emanations. Their placement at the extreme edge of the camp was intentional in order to keep waste, and its smell, as far from the men as possible. Manuals charged junior officers with patrolling the camp, keeping it “clear of filth, holes, and obstructions; clearing the parade and streets every morning.”4

However, a disciplinary tension governed the placement of the latrine. Waste needed to be deposited as far away as possible, but men could not be allowed to leave camp to do their business. Latrines needed to be within the confines of the camp guards’ beat to prevent desertion, something that plagued 19th-century armies. As one military manual ordered, “The soldiers must not be suffered to straggle from the camp; when found a mile from it, without a pass, they are by the articles of war to be reputed deserters.”5 The placement of the latrine in the same proximity of the outer guard was no coincidence.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressIn their letters, diaries, and memoirs, soldiers reported the placement and use of latrines, or “sinks,” varied widely in their units. Seen here (circled) in the foreground of a photo of Fort Morton, a Union position at Petersburg, Virginia, is a sit-down latrine, with a log seat fitted atop two notched logs.

In short, the latrine was a compromise between the twin objectives of curtailing disease and desertion. Placed at the extreme edge of the camp yet under the supervision of guards the ideal sink ensured that the soldier enjoyed no privacy for his most private act. This disciplinary ideal was imagined for professional soldiers, who served their entire careers under military authority. But the American Civil War was not prosecuted by professional soldiers. Trained “regulars” made up only a tiny minority of the servicemen who fought and died. North and South resorted to levée en masse to draw millions of men into service. The antebellum United States had no mandatory conscription system and no coherent militia system. During the conflict, the army’s institutional prescriptions regarding waste management had to compete with a sudden influx of millions of volunteers, almost none of whom were aware of the proper layout of a military encampment, let alone the placement, construction, and maintenance of a latrine. The result was a complete neglect of waste discipline.6

Hardtack and Coffee (1887)

Hardtack and Coffee (1887)Many soldiers avoided digging or using latrines whenever possible; as a result, sanitary conditions in a camp could be abhorrent. Above: An illustration from Union soldier John Billings’ book Hardtack and Coffee depicts two comrades on latrine-digging duty

The 1862 pamphlet Sanitary Conditions of the Southern Army explained the difficulty establishing latrine discipline among recently enlisted volunteers. “One of the strongest reasons why regulars enjoy better health than volunteers is that they are daily inspected by their officers, who insist upon their faces being washed, head combed, &c.” But among the volunteers who made up the majority of Civil War troops, “the regulations of a strict discipline are not enforced and they are allowed to abuse the privilege of following the bent of their own inclinations.” Sanitary Conditions explains a situation in which many male volunteers, fresh from a life of liberties and jealous of their autonomy, refused to accommodate the demands military discipline made on their bodies. The author complained that the “Gentlemen who composed our volunteer regiment would not be ordered to these ditches [latrines]; and as the officers did not insist upon what the men objected to as unnecessarily troublesome, the result was that, with but few exceptions, our regimental camps were accumulations of filth of every description, which could be smelt at a distance whilst approaching them. It was not surprising that disease and death followed in the wake of such indifferences to all laws of decency and hygiene.”7

Sanitary Conditions highlighted how waste indiscipline grew not only from ignorance of military standards, but out of defiance. Civilians roughly pressed into service and eager volunteers alike were repelled by the idea of using, let alone maintaining, latrines. Their hesitance was compounded by the fact that the men ordering them to the latrines were often their former neighbors. The disciplinary regime volunteers found themselves under was often represented by the unlikely characters of small-town lawyers, business owners, and local notables. Historian Andrew Bledsoe, who examines the fraught confrontations between these volunteer officers and the men under their command, argues that men who knew each other as peers and equals in civil life struggled to adjust to the inherent inequalities of the military. He writes, “Since the citizen-soldier ethos encouraged volunteers to guard their democratic prerogatives jealously, Civil War commanders were bound by the limits imposed upon them by their men.”8 The latrine formed just one site of confrontation between newly minted officers and enlisted men, with the latter frequently getting their way.

Evidence suggests that men in both armies dodged duties related to the latrine whenever possible. Iowan Isaac Marsh bragged in October 1862 that “I have got the apointment of first corporal that will exempt me from all fatigue duty such as cooking digging sinks and standing gard.”9 It is not surprising that Marsh was eager to avoid digging latrines. Such dirty work was stigmatized in the 19th century. Historian Alain Corbin outlines in The Foul and the Fragrant how European administrators encouraged the employment of the poor in the creation, care, and maintenance of public latrines. It was believed that the supposedly unhygienic poor were to learn the habits of cleanliness through daily tutoring in cleaning public toilets, accomplishing the dual goal of mental reformation and public sanitation. Similar practices prevailed in urban areas of the United States. In the South, disposal of waste and care for bathrooms and outhouses was reserved for enslaved people. The latrine, therefore, was doubly damned by association with poverty and enslavement.10

The latrine was further stigmatized in Civil War camps by linking it to disciplinary punishment. Officers recognized the enlisted man’s reluctance to both use and maintain latrines and mobilized that aversion for the maintenance of discipline in general. “Blacklisted” soldiers were those found guilty of petty offenses and assigned extra duties as punishment. “Among the tasks that were thought quite interesting and profitable pastimes for the blacklisted to engage in,” noted Union artillerist John Billings in his memoir of army life, Hardtack and Coffee, “were policing the camp and digging and fitting up new company sinks and filling up abandoned ones.”11

There is also the simple matter of emergency, to which Civil War soldiers were not immune. But their responses to the calls of nature challenged military authority nonetheless. Billings remembered that the early-morning ritual of roll call “was always a powerful cathartic on a large number, who must go at once to the sinks, and let the Rebel army wait, if it wanted to fight, until their return.” Every morning, officers had to watch as their authority was undermined by the truism: “When you gotta go, you gotta go.” He concluded, “The exodus in that direction at the sounding of the assembly was really quite a feature.”12

The result of waste indiscipline was that millions of volunteers refused or failed to use the latrine. Soldiers continued to relieve themselves when and where they wished in contravention of military discipline. In a letter home, Union soldier James Pratt complained that an armed guard was required to keep his comrades from defecating on the parade ground: “I am on Guard to day to Guard the Praid Parraid Ground from Nusance we have sinks dug for that Purpace but they will drop It if there is no Guard.”13 Other evidence implies that this was not at all unusual. In 1862, a Union army surgeon complained that “There are frequently some dirty fellows in camp, who defecate inside the camp limits, being too lazy to go to the sink.” The surgeon explained: “Whenever [latrines] are found unclean and offensive, the men will resort to the bushes, &c., in the neighborhood of the camp, and the surgeon may soon expect his sick list to increase.”14

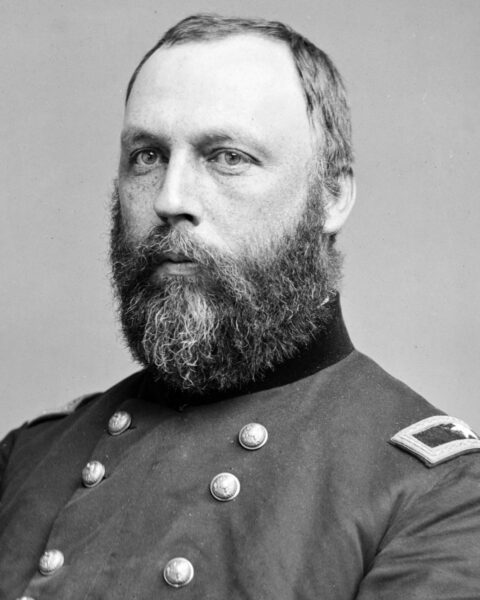

Library of Congress

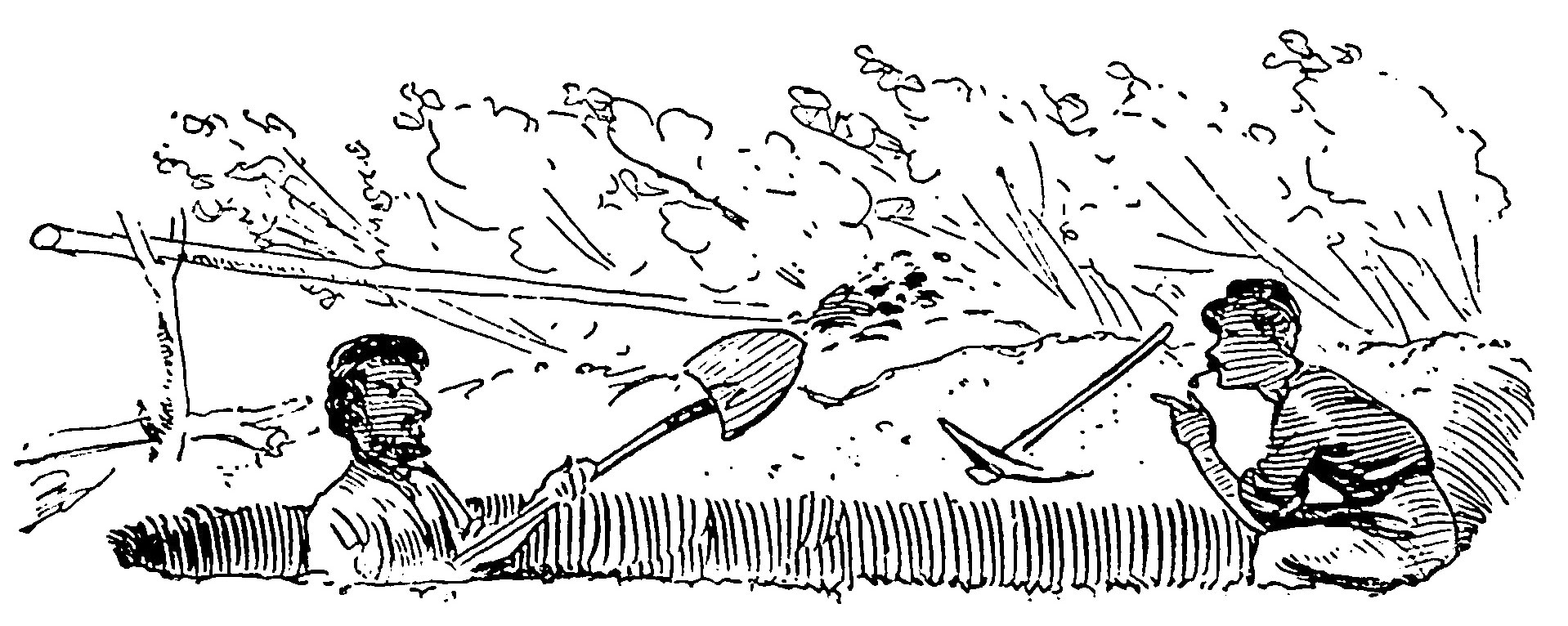

Library of CongressUnion general George G. Meade (above), who lamented the poor sanitary conditions in the Army of the Potomac.

The problem endured throughout the war. Major General George Meade found sanitary conditions abhorrent in the Army of the Potomac on June 5, 1864. “Very few regiments provided sinks for the men, and their excreta are deposited upon hill sides to be washed from thence into the streams, thus furnishing an additional source of contamination to the water[.]” Meade continued, “As is to be expected, under such circumstances, sickness is increasing in the army, diarrhea being especially prevalent.” The Army of the Potomac’s medical director noted that even patients in military hospitals disregarded the latrine in favor of relieving themselves where they wished. “No attention seemed to be paid to cleaning up the grounds immediately in and about the hospital, nor was proper attention bestowed upon the sinks. The ground between the hospital and the sinks had been used for uncleanly purposes by the patients, making it offensive to the sight as well as the smell.”15

The waste indiscipline that plagued army camps must also be blamed on the citizen officers’ lack of understanding of the proper latrine. The Sanitary Conditions observation that “the officers did not insist upon what the men objected to as unnecessarily troublesome,” captures how citizen officers failed to grasp the nature and importance of latrine discipline.16 The newly minted cadre of junior citizen officers in both the northern and southern armies often knew as much about sinks as their men. Their lack of knowledge about proper sanitary practices is illustrated by the frequent corrective orders issued by senior military authorities. General surgeons and high-ranking officers had to remind the amateurs of their duties regarding their men’s effluvia.

Library of Congress

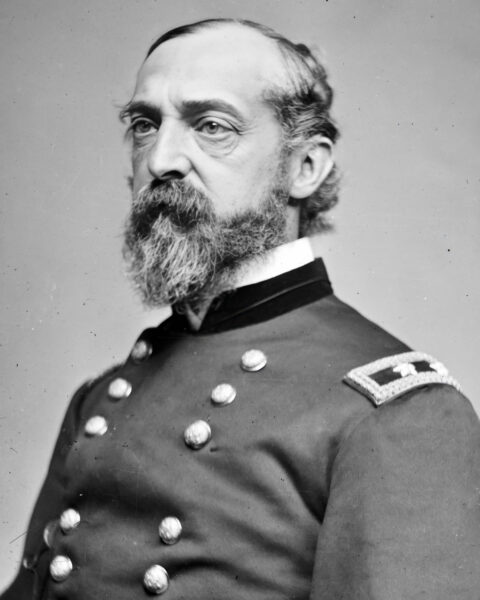

Library of CongressThe sanitary conditions at Fort Davis (pictured above), part of the Union siege lines outside Petersburg, Virginia, were so poor that a general order was issued in July 1864 to try to remedy them.

As late as July 29, 1864, the headquarters of the First Brigade, Third Division of the Army of the Potomac’s V Corps—stationed at Fort Davis, part of the Union siege lines outside Petersburg, Virginia—was compelled to distribute General Orders No. 17. These orders stated that each camp was to be “thoroughly policed every morning” under the “personal supervision of a commissioned officer appointed for that purpose by the regimental commander.” The accumulated “offal, garbage and dirt” was to be swept off the company streets and deposited outside the fort in sink holes “dug for that purpose for each regiment.” Every company was to be provided with boxes and barrels “to hold dirt, slops, garbage, urine, etc.” Trash on the company streets within the fort seemed to be especially troublesome. The order reiterated: “No refuse matter whatever will be thrown on the ground, but will be placed in the boxes and barrels, which will be emptied into the sink holes twice daily[.]” Regarding human waste, General Orders No. 17 outlined that officers and men should not be allowed to urinate within the walls of the fort during the day, and only use specially constructed urinals at night. In addition to each regiment’s sink for garbage, the order mandated that each regiment construct another sink for human waste, located 100 yards from the fort. They were to be covered with a layer of dirt every day. A special sink was to be constructed for the use of the officers of the brigade.

The brigade’s commanding officer also noted that, since “all officers and men must see the necessity of a strict observance of the above regulations in the present crowded state of the command,” he expected “prompt and cheerful compliance with all measures he may adopt to promote comfort, cleanliness, and prevent disease.” Perhaps recognizing that the volunteers under their command had never been made aware of these disciplinary standards, General Orders No. 17 included the directive, “This order will be read to each company in the command.”17

Citizen officers, when they bothered to think of latrines at all, frequently left their construction and use to the enlisted men. This anarchic approach resulted in the random placement of latrines—which often led to disgusting consequences. James Emmerton of the 22nd Massachusetts Infantry recalled with “grim humor” how a party of his comrades, caught between Union and Confederate lines during the Siege of Petersburg, dived into “What seemed, in the half-light, rifle-pits deserted by the enemy” but immediately “another sense came into play. As they lay low to escape the whizzing bullets, their noses informed them that the rebels did not dig, nor use, those holes for riflepits.”18 Servicemen in both armies were always at the hazard of an incorrectly placed latrine. A Union artillerist remembered that during battery drill, which entailed large teams of horses, cannon, and caissons rapidly maneuvering through open areas, the threat of a randomly placed latrine was omnipresent. The cannoneer remembered clinging to a caisson and “momently expecting to be hurled head-long as the carriages plunged into an old sink or tent ditch or the gutter of an old company street….”19

Library of Congress

Library of CongressWilliam Alexander Hammond

It would be unfair to attribute the absence of proper latrine discipline completely to the ignorance of citizen officers. Many of the mistakes and misplacements were motivated by a genuine desire to pursue the most healthful and sanitary practices. Guided by the prevailing conceptions of disease, namely that miasmatic air caused illness, amateur officers looked to remove filth from the camp to the greatest extent possible. It seems equally likely that, guided by the same fear of miasma, officers permitted their men to relieve themselves where they wished beyond the confines of the camp in order to disperse the smell and waste as much as possible. It is also important to note that the citizen officers were not immune from the same hostility to military discipline that the men under their command evinced. Many were no less inclined to potty train their men than their subordinates were inclined to accept such condescension.

Ignorant citizen officers, reluctant volunteers, and chaotic circumstances, however, do not deserve all the blame for the failure of latrine discipline during the war. Even the best attempts to construct proper latrines collided with institutional confusion regarding waste management. In particular, a dangerous incoherence reigned regarding the latrine’s relationship to running water. As William Alexander Hammond, surgeon general of the U.S. Army, advised in his 1863 Treatise on Hygiene: With Special Reference to Military Service, “Latrines should not be made over streams of water or in the vicinity of springs or wells. In either case the water will become contaminated, and serious disease may be the result.”20 In contrast, the adjutant general of Georgia provided the opposite advice to the state’s militia: “Your camp will be selected, having a view to an abundant supply of water….” While the order did not stipulate the location of the latrines, the adjutant general noted that “The location of the site of your camp under these instructions is left with yourself.”21 The same confusion reigned in Federal military facilities. Union surgeon Charles Smart recounted that in one prisoner of war camp in the North, “The sinks were at first simply pits, from which the accumulations were removed by carts and thrown into the river. At later dates these were abandoned and a large latrine was constructed in the prison, communicating with the river by means of a trench. Daily flushing swept the deposits into the river.”22

The consequences of widespread and longstanding latrine indiscipline were epidemics of waste-borne disease. Linking latrine indiscipline to epidemic disease can be challenging due to the incongruity between modern epidemiological practices and available sources from the Civil War. However, evidence from both soldiers’ accounts and official records allows for substantial links to be made between latrines and outbreaks of disease. Improper placement and management of latrines contaminated water supplies, leading to dysentery and other deadly illnesses.

Lyman Beebe of the 151st Pennsylvania Infantry captured how the latrine formed the locus of gastrointestinal disease in a Civil War camp. In January 1863 Beebe complained that, “I was taken with the back door trot day before yesterday and from dark to the next morning I went from my quarters to the sink eight times before morning[.]” This spell of diarrhea left Beebe “so reduced I did not know as I but should be able to get there when I started,” perhaps implying that once or twice he did not make it. This awful experience was compounded by rain and snow that transformed the “thirty and forty rods” to the latrine into a morass of shoe-deep mud. Beebe reported himself sick and was given some medicine “which helpt me right away,” but he still felt “very weak the diarhea is the prevailing disease here now[.]”23 North Carolina soldier James Zimmerman also captured the geographic problem of waste disposal in camps. He wrote on December 2, 1862, “there was a man died last night going to the sinks with the diarear that is two that has died very sudden in a short time.”24 An Ohioan complained in the fall of 1863, “I dont feel very wel have to run to the Sink most to often but think I shal get beter in a fu days.”25

While these accounts from soldiers in camp do not elaborate on the relationship between latrines, waste, and contaminated water, army surgeons realized what was happening. In one Federal camp, one of them noted, “The two hospital tents of the battalion were situated on the low ground near the head of a small ravine; there was a shallow sink not more than twenty-five feet behind one of them and above it, the ground being higher than in front.” The surgeon analyzing the situation concluded, “The four typhus cases occurred in the tent on the low ground near the sink.” Union army assistant surgeon Henry S. Schell analyzed a similar outbreak of fever in a camp in Miner’s Hill, Virginia, in 1862. “In estimating the causes of this disease” Schell attributed the outbreak to “exposure to effluvia of badly regulated sinks, half or totally unburied offal from slaughter pens and excrement deposited in improper places, and the continued occupation of the same camping ground.”26

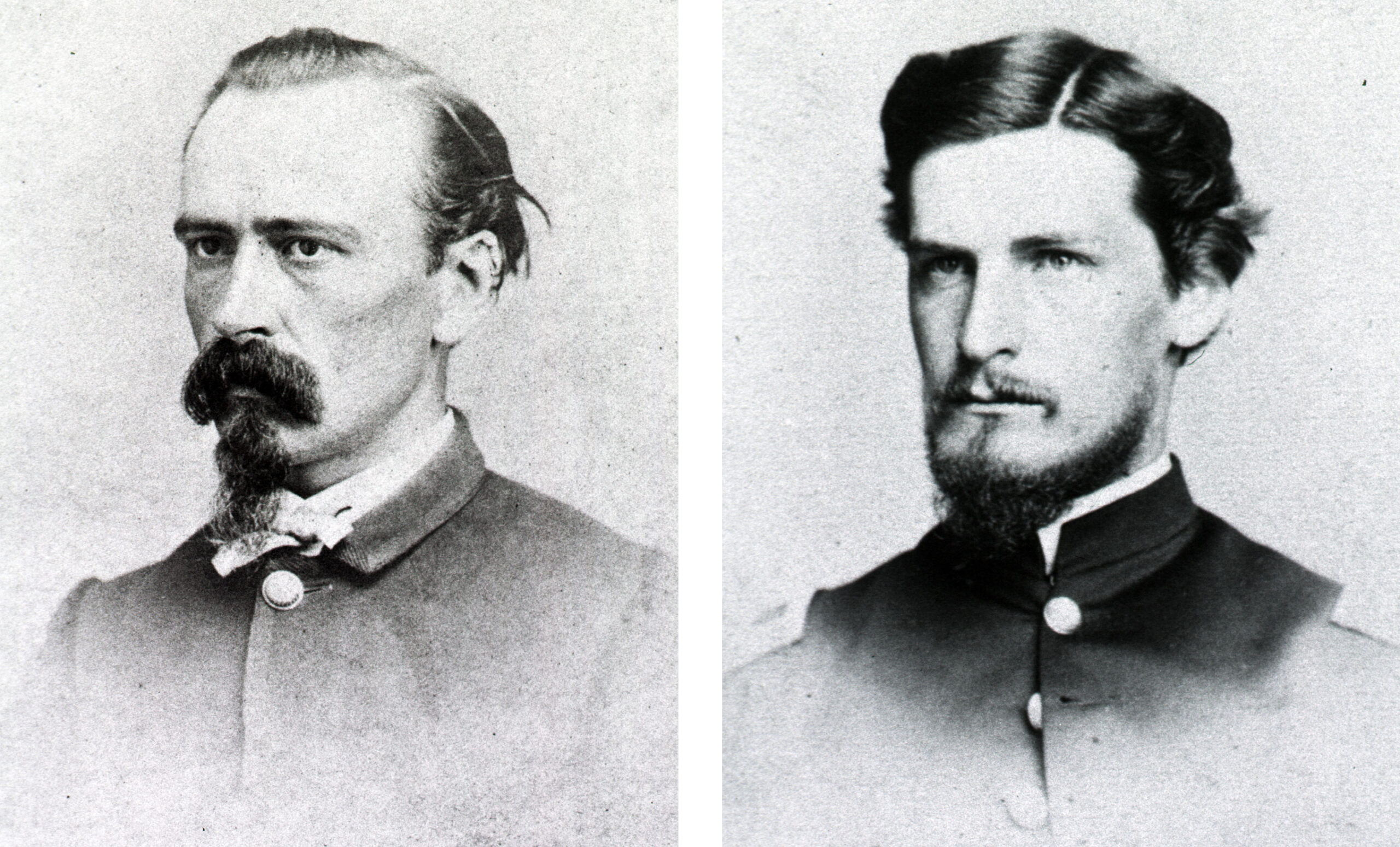

National Library of Medicine (2)

National Library of Medicine (2)Charles Smart (left) and Henry S. Schell

Latrines were killing the men of the armies and this fact was not lost on the medical officers charged with maintaining soldiers’ health in wartime. But what surgeons and officers should and could do to solve this problem was more ambiguous. Textbooks illustrated the proper methods of construction and placement of latrines but failed to provide guidance for what to do if the men refused to use them. Some surgeons addressed the problem by adopting a disciplinary role and forcing men to use the latrine.

On May 12, 1863, Jonathan Letterman, medical director of the Army of the Potomac, was compelled to reissue an order first distributed in 1861. The cause: waste indiscipline. “In every camp sinks should be dug and used, and the men on no consideration be allowed to commit any nuisance anywhere within the limits of this Army.” Letterman reiterated the military regulations for depth and maintenance, and emphasized their importance by noting “No one thing procures more deleterious effects upon the health than the emanations from the human body, especially when in process of decay; and this one item of police should receive special attention.”27

Letterman recognized that this was first and foremost a disciplinary problem. The continued failure to achieve correct military waste management required that disciplinary considerations be emphasized. He realized that the junior officers of the Union army were not completing their assigned duty of managing the latrine. Letterman complained, “Spasmodic effects, in a matter of such paramount importance as police in an army, can be of no service,” he wrote. “I recommend that regimental and other commanders be required to see that these suggestions, if they meet the approval of the commanding general, be full and continuously carried into effect.”28

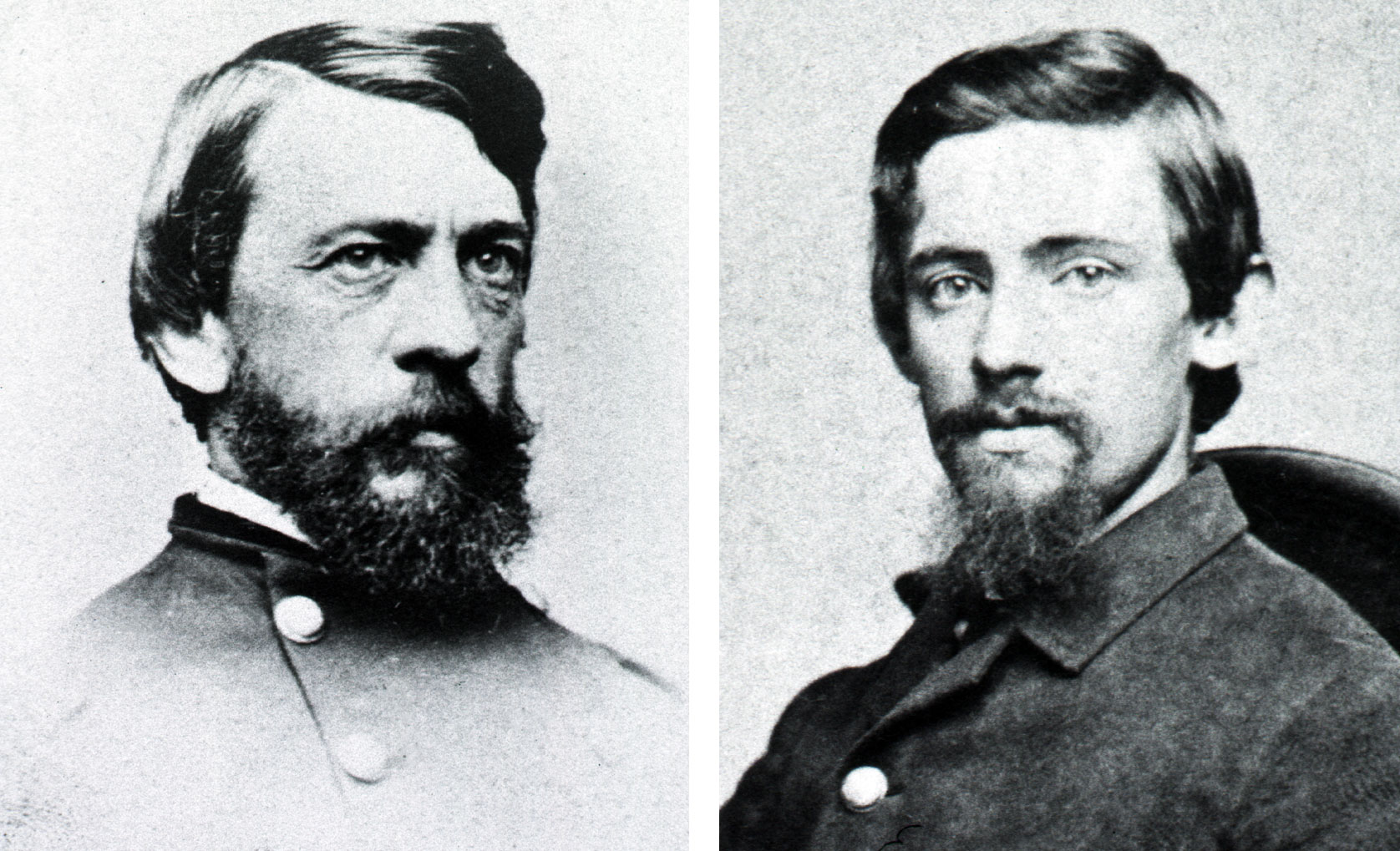

National Library of Medicine (2)

National Library of Medicine (2)Jonathan Letterman (left) and J.T. Calhoun

Letterman was typical of Civil War surgeons in responding to the failure of military waste management by calling for greater discipline. The surgeon, seemingly separate from the military hierarchy, actually assumed a prominent role in controlling the movement of the private soldiers in his unit during the war. J.T. Calhoun, a surgeon serving in the Union army, wrote to the Medical and Surgical Reporter in 1862, explaining the role he and his colleagues played in the hierarchy of military authority. “As a colonel is responsible for the discipline and military training of the regiment, the surgeon has the far greater responsibility of the health of the command.”29

Latrines were a focus of the surgeon’s mandate to establish discipline. In 1863, the North American Review published “A Treatise on Military Hygiene,” which instructed its readers that volunteers “must be under strict police, with regard to latrines, slaughter and cooking places, and all rubbish.”30 Calhoun agreed that “Well regulated sinks are essential to a good regiment…. An illy disciplined regiment can always be known by its dirty sinks.”31 Military surgeons understood that this was linked to the volunteers’ ignorance of the importance of latrine discipline. “The habits of the soldiers are, almost unavoidably, somewhat dirty,” noted the author of the “Treatise on Military Hygiene.” “Removed from the customary conveniences of home,” the volunteer “inevitably becomes careless and filthy unless prevented by the strictest discipline. All this operates to engender, communicate, and prolong disease.”32 In order to preempt the spread of disease, surgeons needed to establish a disciplinary control over the volunteer to prevent behaviors that spread disease.

Surgeons’ focus on curbing volunteers’ bad habits provides more insight into waste indiscipline during the war. Calhoun complained that most instances of waste indiscipline were “done at night, and when caught the offender should be severely punished.” He outlined other unacceptable practices related to waste. “A more common and but little less dirty habit is that of urinating in the company streets. In the Rebel army this is always considered a punishable offence. I am sorry to admit that in many regiments of our own army this is not the case.” Calhoun concluded, “By all the laws of decency and propriety, to say nothing of health, officers and men should be compelled to go to the latrine to urinate, and prompt punishment should follow detection of any culprit caught disobeying the order.”

While most military manuals provided vague commands to enforce the “strictest policing,” Calhoun provided specific instructions for his fellow doctors in arms in how to punish offenders against latrine discipline. “A most effectual punishment was used last winter in some camps. The head of the offender was thrust through a barrel, which rested upon his shoulders and encircled him on all sides. The offensive matter was then shoveled on the barrel head, directly under the offender’s nostrils, and thus he was paraded around camp. He would never be guilty of the offence a second time.”33

Mobilization during the Civil War has been viewed as a huge boon for government authority, as massive swaths of the population experienced a direct relationship with the military for the first time in their lives. But from the perspective of the latrine, mobilization and the assertion of governmentality over the American populace was constantly incomplete and disastrously ineffective. There simply weren’t enough trained eyes on the volunteers of the Union and Confederate armies to ensure that they constructed and used the correct facilities and maintained them properly. Ideological aversion to the latrine and its maintenance, general ignorance of proper latrine discipline, and the irresistible call of nature made the creation and use of the military latrine difficult.

Recent scholarship on mass indiscipline during the Civil War advances the idea that the failures of discipline were sometimes more important than their successes.34 The Confederacy, it is proposed, collapsed due to the mass desertion of soldiers and enslaved people alike.35 The latrine represents another disciplinary failure with far-reaching consequences. Strict latrine discipline was rarely implemented and often ignored. Epidemic disease ravaged the field armies on both sides, sometimes substantially affecting their ability to achieve strategic objectives.36 At least some of the blame for these epidemics must be attributed to the unused, unmaintained, and unconstructed latrines of the Union and Confederate armies.

The story of latrine indiscipline does not end in 1865. The urban reforms of the 19th century and the massive technological advances of the 20th and 21st centuries revolutionized waste management, with resultant declines in disease and mortality. However, military mobilization has yet to completely escape the deadly consequences of waste indiscipline and consequent disease. United Nations peacekeepers from Nepal were dispatched to Haiti in the wake of the 2010 earthquake. The Nepalese soldiers unknowingly brought cholera with them, and after their arrival, the disease passed to the Haitians. The researcher responsible for identifying the cause of this disaster wrote that “the negligent and haphazard sanitation facilities within the U.N. base itself” was the “immediate cause” of the outbreak. A United Nations expert panel admitted “that the construction of sanitation and water pipes was haphazard” and that the improper construction of latrines “led to the contamination of the tributary by human waste flowing out of the U.N. base.” In 2013, it was hypothesized that the epidemic had killed 8,000 and sickened over 600,000 in Haiti.37

Military mobilization and proper latrine discipline remain unmastered problems of even the most technologically adept international organizations. The cholera outbreak in Haiti is a grim reminder that the past is present, and the disciplinary projects of the 19th century remain unfinished today.

Ben Roy is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia who specializes in the social and cultural history of the Civil War. His research on Confederate monuments was recently published in The Public Historian and he is currently completing work on the legal attempts to conscript resident aliens into Confederate service.

Notes

1. Eyewitness to the Civil War: The Complete History from Secession to Reconstruction, ed. by Neil Kagan and Stephen G. Hyslop (Washington, D.C., 2013), 344. “Disease and Medical Care,” John Terrill Cheney Exhibit, U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center.

2. Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (Baton Rouge, 1952) and The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (Baton Rouge, 1943).

3. “Disinfectants,” Medical and Surgical Reporter, December 26, 1863; Ruth Goodman, How to be a Victorian: A Dawn to Dusk Guide to Victorian Life (New York, 2015); The Historical Archaeology of Military Encampment During the American Civil War, ed. by Gerald R. Orr et. al. (Tallahassee, 2006).

4. John Letterman, Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac (New York, 1866), 14. William Duane, The American Military Library; Or, Compendium of the Modern Tactics (Philadelphia, 1809), 170–175, 185.

5. Duane, The American Military Library, 170–175; Mark A. Weitz, More Damning than Slaughter: Desertion in the Confederate Army (Lincoln, 2005).

6. Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb, 15, The Life of Billy Yank, 17.

7. “Review of The Sanitary Condition of the Southern Army,” Medical and Surgical Reporter, November 1,1862.

8. Andrew Bledsoe, Citizen Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (Baton Rouge, 2019), 23–24.

9. Isaac Marsh (Marsh Papers Duke), quoted in “Gone up the Spout,” Private Voices.

10. Alain Corbin, The Foul and the Fragrant: Odour and the Social Imagination (New York, 1968), 117, 173; Seth Rockman, Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore, 2009), 1–2; Eugene Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York, 1974), 550–561.

11. John Billings, Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life (Lincoln, 1885, 1993), 145.

12. Ibid., 167.

13. James Pratt to Charlotte Pratt, October 2, 1862, James and Charlotte Pratt Papers, U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

14. J.T. Calhoun, “Rough Notes Of An Army Surgeon’s Experience During The Great Rebellion: No. 4, The Camp, Its Location, Latrines,” Medical and Surgical Reporter, November 8, 1862 (hereafter cited as “Rough Notes”).

15. Both sources quoted in Carole Adrienne, “What are Civil War Sinks (Latrines)?” Civil War RX: The Source Guide to Civil War Medicine.

16. “Review of The Sanitary Condition of the Southern Army,” Medical and Surgical Reporter, November 1, 1862.

17. Order quoted in Levi Wood Baker, History of the Ninth Massachusetts Battery (Framingham, MA, 1888), 129–130.

18. James Arthur Emmerton, A Record of the Twenty Third Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865 (Boston, 1885), 222.

19. Billings, Hardtack and Coffee, 184.

20. William Alexander Hammond, A Treatise on Hygiene: With Special Reference to Military Service (1863), 460.

21. Adjutant and Inspector General of Georgia to Brigadier General Mercer, May 19, 1863, Adjutant General’s Letter Book Volume No. 15, 414, Georgia State Archives, Morrow, GA.

22. Charles Smart, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (Washington D.C., 1888), 1: 52 (hereafter MSH).

23. Lyman Beebe to Phebe Beebe, January 26, 1863, Lyman Beebe Papers, U.S. Army Military History Institute, quoted in Private Voices, altchive.org/node/14248.

24. James Zimmerman, Zimmerman Papers, Duke University, quoted in “Gone up the Spout,” Private Voices.

25. Charles Caley, University of Notre Dame, quoted in “Gone up the Spout,” Private Voices.

26. MSH, 1: 273, 328.

27. Letterman, Medical Recollections, 147.

28. Ibid., 14, 148.

29. Calhoun, “Rough Notes.”

30. “ART. IX—A Treatise on Hygiene,” The North American Review vol. 97, no. 201 (1863), 483-507.

31. Calhoun, “Rough Notes.”

32. “A Treatise on Hygiene,” 483–507.

33. Calhoun, “Rough Notes.”

34. James C. Scott, Two Cheers for Anarchism (Princeton, 2012), 8–10.

35. Steven Hahn, A Nation Without Borders: The United States and Its World in an Age of Civil Wars, 1830–1910 (New York, 2016), 548; Peter S. Carmichael, The War for the Common Soldier: How Men Thought, Fought, and Survived in Civil War Armies (Chapel Hill, 2018), 79–87, 174–230.

36. Kenneth Noe, The Howling Storm: Weather, Climate, and the American Civil War (Baton Rouge, 2023), 203–227; Megan Kate Nelson, The Three Cornered War: The Union, the Confederacy, and Native Peoples in the Fight for the West (New York, 2020).

37. “Haiti’s Cholera Outbreak Tied To Nepalese U.N. Peacekeepers,” All Things Considered, National Public Radio, August 12, 2013.