National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

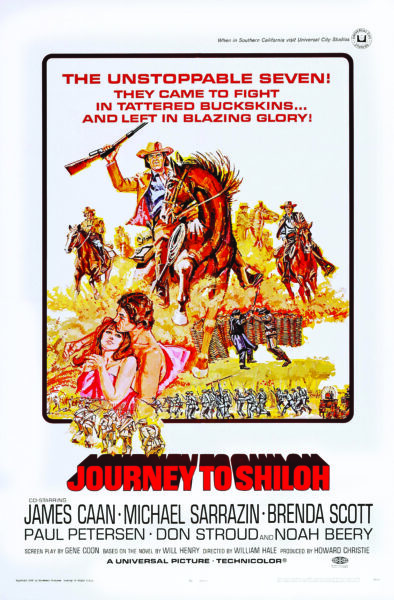

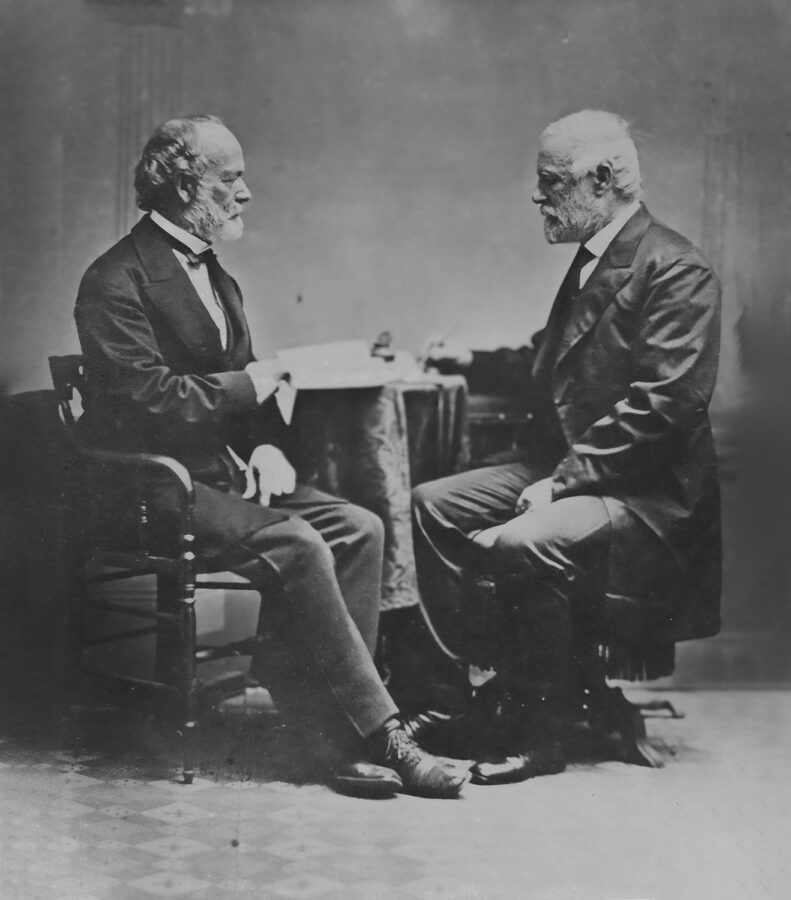

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionFormer Confederate generals Joseph E. Johnston (left) and Robert E. Lee sit together in this photograph made in 1870. Lee died later that year, never having written a memoir of this wartime experiences. Johnston published his memoir in 1874.

Students of the Civil War are blessed with an abundance of personal narratives from thousands of people, some famous, most not. From the former, we have memoirs by Union soldiers Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, George Brinton McClellan, Philip Henry Sheridan, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, and many others. From famous Confederates, the list includes Jefferson Davis, Joseph Eggleston Johnston, Jubal Anderson Early, James Longstreet, Richard Taylor, John Bell Hood, Edward Porter Alexander, John Brown Gordon, John Singleton Mosby, and many more.1

From this roll there is one famous absentee: Robert Edward Lee. He did not write a memoir, so we don’t have his accounts, for example, of the Virginia campaigns that ended at Appomattox in April 1865. The memoir boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries gave us Grant’s version of the surrender, but we can’t compare it with Lee’s, the way we can compare Sherman’s version of the surrender at the Bennett farmhouse in North Carolina with his counterpart Joe Johnston’s account.

On the major events in the eastern theater of war from 1862 to 1865, from the Peninsula Campaign to the breakthrough at Petersburg and the week that followed, we do not hear from Lee, at least not in memoir form. On April 21, 1865, in Richmond, Lee gave Thomas M. Cook of the New York Herald his only formal postwar interview (it produced a paraphrase by Cook, not a verbatim transcript), and in February 1866 Lee gave recorded testimony in Washington, D.C., before the Joint Congressional Committee on Reconstruction. Otherwise, there are only Lee’s private letters and statements to others, later reported by them. These are valuable, but they’re not the same as a book of some heft written by him.2

Lee was 63 when he died in 1870, before the postwar memoir boom of that decade and the next. So he died too early? For Lee’s irascible lieutenant general Jubal Early, until 1870 was more than enough time to rush a memoir into print. Having lit out for Canada immediately after the war ended, Early had by 1866 published A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence in the Confederate States of America with the Toronto firm Lovell and Gibson. If Lee had had more of Early’s spleen and devotion to promoting the Lost Cause view of the war, he could have done the same. Then again, if Lee had been more like Early, the war may have had a more protracted and much messier ending. Early’s example counters the argument that “Lee died too soon.” Behind the absence of a memoir hovers a bigger story about Robert E. Lee, a story that can be sketched around a few key dates.

1812

This is the year Robert turned 5 and his father, Henry Lee, published Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States with the Philadelphia publisher Bradford and Inskeep. The title page identified Lee as “Lieutenant Colonel Commandant of the Partisan Legion During the American War.” The page also includes an epigraph from Virgil’s Aeneid, showing that the author claimed not only military authority and standing but also a classical education. The line is a famous one, spoken by Aeneas to Dido about the sack of Troy: Quaeque ipse miserrima vidi / Et quorum pars [magna] fui. (“And most terrible things I myself saw, and of which I was a [great] part.” Lee’s title page omitted Virgil’s magna.)

Iandagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo

Iandagnall Computing / Alamy Stock PhotoHenry Lee III (shown here in an early 19th-century painting by Gilbert Stuart) wrote an account of his wartime service in the Revolutionary War, where he earned the nickname “Light-Horse Harry” for the speed with which he maneuvered against British forces. One of his sons grew up to be a famous Confederate general but not a memoirist.

What the title page does not say is that the author Henry Lee was Henry Lee III, nicknamed “Light-Horse Harry” for the speed with which his mixed legion of cavalry and infantry maneuvered and struck the British during the American Revolution. Nor does the book say that after the war he served as governor of Virginia and as its congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives. It does not say that he married his second cousin, Matilda Lee, who had inherited Stratford Hall, where the young family lived; it does not say that Matilda died and that Light-Horse Harry then married Ann Hill Carter, with whom he became the father of Robert Edward Lee and his siblings. And it does not say that he wrote a large part of this memoir during 1809 and 1810 in the Spotsylvania County jail, where he was imprisoned for debt. But to a second key date:

1815

There appeared this year the Catalogue of the Library of the United States: to which is annexed, a copious index, alphabetically arranged, printed in Washington, D.C., by Jonathan Elliot. This catalog, of over 6,000 books that formed the nucleus of the Library of Congress, was based on Thomas Jefferson’s list of his personal library, which he offered to the nation after the British burned the congressional library in 1814. What matters here is the classification system Jefferson used. “Books may be classed according to the faculties of the mind employed on them: these are—I. MEMORY. II. REASON. III. IMAGINATION.” In this way, Jefferson introduced a scheme borrowed from an 18th-century encyclopedia, as he mapped the mental faculties onto three areas of knowledge, so that Memory, Reason, and Imagination corresponded respectively to History, Philosophy, and Fine Arts.3

Iandagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo

Iandagnall Computing / Alamy Stock PhotoWhile serving as superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in the 1850s, Lee (depicted here as he appeared then) was approached to write about his life for a series of biographical encyclopedias. He declined the offer.

The result was 44 subdivided classes of books, each a numbered “chapter” in this scheme. Chapter 4, for example, is labeled “American,” under the general heading History. Here Jefferson placed his copy of Henry Lee’s Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States, one of 78 books he listed under American History. Five others had the word “memoir” or “memoirs” in their titles.

What’s notable is that Henry Lee’s book and the other memoirs Jefferson owned show that the word “memoir” meant something different to 18th- and 19th-century authors and readers than what it means today. To Lee, to Jefferson, to the Englishman Samuel Johnson, whose dictionary of the English language came out in 1755, to founding father Noah Webster, whose American Dictionary of the English Language appeared in 1828—to those men memoir didn’t have to mean anything either autobiographical or personal.

The word “memoir” meant something different to 18th- and 19th-century authors and readers than what it means today.

Webster defined memoir as “A species of history written by a person who had some share in the transactions related,” adding, “Persons often write their own memoirs.” But apparently often they didn’t. Light-Horse Harry Lee did not. He certainly had some share in the transactions related, as did Aeneas in the war at Troy. But Lee wrote his memoir mostly about his superior, General Nathaniel Greene, not about himself.

1854

The year of the Kansas-Nebraska Act found Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee serving as superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Lee held the position, which he accepted reluctantly, from 1852–1855, when he was transferred to the cavalry in Texas. And this year his oldest son, Custis, graduated from West Point. And this same year, Lee received a letter from New York lawyer-editor-entrepreneur John Livingston asking him to write about his life for a series of biographical encyclopedias with titles such as Biographical Sketches of Distinguished Americans Now Living, Livingston’s Portraits and Memoirs of Eminent Americans Now Living, and Portraits of Eminent Americans Now Living.

Whether beyond the military academy Robert E. Lee would have been considered eminent in 1854, he certainly had distinguished himself serving under General Winfield Scott in the Mexican-American War of the 1840s. Nevertheless, Lee turned Livingston down. In a letter dated October 20, 1854, written from West Point, he wasted no time: “I have recd your letter calling my attention to the American Portrait Gallery & am very much obliged to you for your kind offer to place my name in its pages. I fear the little incidents of my life would add nothing to the interest of your work, nor would your readers be compensated for the trouble of their perusal. I must therefore gratefully decline your proposition; but being fully sensible of the value of the work, accept your offer of the 4 Vols. now published, which I propose to place in the library of the Acady, in the hopes that the memoirs of men, who have acquired distinction & usefulness[,] may have their effect upon the characters of the Cadets, & excite them to exertion & industry.”4

People can disagree about how to read this letter. Some may hear false modesty, others the self-effacing humility of a military officer. Whatever modern readers may hear, it would be difficult to miss the undertones from the writer for whom the standard of those “who have acquired distinction & usefulness” was very high. In the worldview of Robert E. Lee, not every prominent man was above average and not every prominent man deserved a trophy.

Not only was the bar high for a man’s distinction and usefulness, it was high for his memoirs, and so for Lee. Perusal of such memoirs must, he believed, enhance the characters of future leaders, in this case military ones, and “excite them to exertion & industry.” Brevet Colonel Lee had no liking for a distinguished person’s memoir if all it did was air grievances while justifying the record of the writer, especially one who indulged in boasting and blaming. The Civil War produced plenty of such memoirs, particularly among Union and Confederate generals, and were a long-lost such memoir to appear now, resurrected from somewhere, it might soar to bestseller status. But in 1854 the West Point superintendent saw nothing appealing in publicizing himself.

1861

“Key” is inadequate for the significance of this year in Lee’s never-written memoir—the year of the April bombardment of Fort Sumter and the beginning of the War of the Rebellion, as it was to be called in the government printing of Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. But the historic date also matters because it marks the appearance of the first personal wartime narratives, the first Civil War memoirs. Among the earliest was one written by Alfred Edward Mathews, a typesetter and artist in Ohio. He later served in the 31st Ohio Infantry, and during his service he made sketches of Vicksburg, which Grant, the city’s captor, praised. In his book, printed by an unknown press in New Philadelphia, Ohio, Mathews dated his introduction July 1861, the month of the Battle of First Manassas. The whopper of a title reads Interesting narrative: being a journal of the flight of Alfred E. Mathews, of Stark Co., Ohio, from the State of Texas, on the 20th of April, and his arrival at Chicago on the 28th of May, after traversing on foot and alone a distance of over 800 miles across the States of Louisiana, Arkansas and Missouri, by the most unfrequented routes; together with interesting descriptions of men and things; of what he saw and heard; appearance of the country, habits of the people, &c., &c., &c.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionWhen he penned his memoir in 1863, Mexican War veteran and former General-in-Chief Winfield Scott (shown here in a photograph from 1861) was clear about his motivation: “The English language is singularly barren of autobiographies or memoirs by leading actors in the public events of their times.”

Mathews’ “interesting narrative” is significant because it shows that Civil War generals did not invent personal narratives or pioneer the war memoir genre. Personal wartime narratives came from women as well as men, southerners and northerners, civilians and combatants, professional writers and amateurs. Many of the earliest narratives recounted ordeals in prisons or in hospitals. Louisa May Alcott’s Hospital Sketches (1863) and Sarah Edmonds’ Nurse and Spy (1865) are well-known examples that appeared even before Jubal Early’s book. By 1885, when Grant wrote his memoirs, the genre was in full swing. If Lee had managed to write one before he died, his father’s memoir would not have been his only model. He and his publisher would have had to figure out how to bring his contribution into an established marketplace.

Civil War generals did not invent personal narratives or pioneer the war memoir genre.

1863

This year was key for the Emancipation Proclamation, Lee’s victory at Chancellorsville, the death of Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson there, Grant’s capture of Vicksburg, and Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg and retreat across the Potomac River into Virginia. The same year was spent by former commanding general of the United States Army Winfield Scott (Lee’s superior in Mexico) writing his memoir. Scott was born in Petersburg, a detail that complicates his attempt in 1861 to persuade Lee to choose serving the United States over serving their home state. Though Scott neither owned slaves nor supported slavery, his anti-slavery position had cost him in the presidential election of 1852, which he lost in a landslide to Franklin Pierce.

As Abraham Lincoln came to rely more and more on McClellan in the first months of the war, Winfield Scott stepped aside and retired to West Point, where he wrote his book. Published in New York by Sheldon and Company in 1864, Memoirs of Lieut.-Gen General Scott, LL. D. / Written by Himself shows that Scott wanted to differentiate his book from Henry-Lee-style memoirs of people written by other people. He dated his introduction July 5, 1863, two days after Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg and the day after Vicksburg surrendered to Grant. The opening provides a significant benchmark in the history of American memoirs as Scott wrote: “The English language is singularly barren of autobiographies or memoirs by leading actors in the public events of their times. Statesmen, diplomatists, and warriors on land or water, who have made or moulded the fortunes of England or the United States, have nearly all, in this respect, failed in their duty to posterity and themselves…. It was otherwise with very eminent men of antiquity.”

Scott’s list of those memoirists led with Moses and Joshua before adding the examples of two generals, Xenophon and Julius Caesar, one Greek, one Roman, whom the learned Scott hoped to emulate. One way he did that was in his choice of personal pronouns, Xenophon and Caesar having written about themselves in the third person. Although Winfield Scott began his memoir in the first person, by Chapter 6 and the War of 1812, he was Lieutenant-Colonel Scott, in the third person for the rest of the narrative. Looking back to 1863, we read someone quite distinguished stating that the country suffered from a dearth of memoirs by eminent people who play leading roles in the events of their times. That claim could not be made a mere 25 years later.

1869

This was the year Grant was sworn in as the nation’s 18th president and the golden spike was hammered down in Promontory, Utah, completing the first transcontinental railroad, a project in which Sherman was deeply involved. It was also the year Charles B. Richardson, a publisher in New York and Baltimore, brought out a third edition of Henry Lee’s Memoirs in the Southern Department of the United States. It opened with a new 70-page section titled “The Life of General Henry Lee” written by the president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia, and former General-in-Chief of the Armies of the Confederate States Robert E. Lee.

The story of Lee’s involvement with Richardson had begun on May 5, 1865, just weeks after Appomattox. Richardson wrote to Lee, “With regard to the suggestion I made to you referring to the proposed volume upon your campaigns, it is suitable that you should know to what extent I feel a personal interest in the matter. Having already issued several volumes relating to the Confederate cause, it would be specially gratifying to add to the number such work as would come from your pen.”5

What was Richardson’s angle? Descended from a long line of New Englanders, Richardson would soon publish Virginia journalist Edward A. Pollard, whose pro-Confederate histories of the war originated the term “Lost Cause.” Was Richardson a northern Copperhead? Was he, as he suggests in the letter to Lee, genuinely interested in reconciling the warring sections? Was he a sharp Yankee with a nose for business? Was he all of these?

What we know from Richardson’s correspondence with Lee is that his goal was to publish a book by Lee about the history of the Army of Northern Virginia. Publishing the third edition of Henry Lee’s memoirs was one of Richardson’s strategies for coaxing Lee to sign a contract for a historical memoir of his army. Because one of Lee’s big problems in attempting to write such a book would have been the loss or destruction of Confederate records, Richardson’s other strategies included sending Lee new books about the war, reports by northern generals, all the paper Lee would need, and a golden pen. He also offered to make substantial contributions to the Washington College library.

Thanks to a 1963 essay by Allen Wesley Moger, who taught at Washington and Lee for almost 60 years, we know a great deal about Lee’s dealings with Richardson and with many other publishers, American and British, who also went after Lee. This passage appears in a letter Lee wrote to his older brother Charles, dated August 18, 1865: “As regards the publication of the works proposed by Mr Richardson, he offered to pay me if I should prepare them, 10% per cent on the retail price of each work, he taking upon himself the whole expense. He spoke of it as the usual price. Of that I do not know, but all the profits on our fathers memoirs you can take. I am fully alive to the propriety of making both works if possible a source of profit. For I have to labour for my living & I am ashamed to do nothing that will give me an honest support.”6

This letter tells us that months after Appomattox, Lee was thinking about money and his need to earn it. He does not sound like an aristocrat unwilling to soil his dignity by doing business. His motives were twofold. First, he wanted to make sure northern writers didn’t exercise exclusive control over narratives of the Civil War, particularly when it came to his beloved Army of Northern Virginia. Second, he needed an income. In this respect, he was like his counterpart, Grant, who years from now would lose his money in a Wall Street swindle and find himself with not even a pension for having served as General of the Army or two-term president of the United States.

So along with Lee-died-too-young, we can throw out Lee-didn’t-want-to-talk-about-the-war-in-any-partisan-way and Lee-didn’t-want-to-stoop-to-business-concerns to explain his reluctance to write a memoir. And discard Lee-was-too-sick; nobody was sicker than Grant (both men died at 63) when he wrote his memoirs, suffering from cancer in his throat and jaw, his doctor dosing him every day with combinations of morphine, cocaine, and brandy.

Lee, despite the heart trouble from which he suffered during the war, was healthy enough to write the introductory 70-page biography Richardson asked for, the longest prose piece Lee ever composed. True, a memoir of the same gravity as Grant’s or Sherman’s or Johnston’s or Longstreet’s would need to be 10 times as long. But those pages give the reader an idea of what a longer memoir by Henry Lee’s famous son might have been like.

What kind of 700-page book would Robert E. Lee have produced? Historians and writers who have weighed in on the subject tend to agree it would have been tough going and possibly disappointing. Consider two statements by prominent admirers of Lee who studied and thought about him a good deal. Gamaliel Bradford in Lee the American (1912) writes: “Here [in Lee’s biography of his father], as in so many other matters, we see curiously the inheritance of the eighteenth century, its dignified finish, its determination to clothe even common things in lofty phraseology.” “Lofty phraseology” doesn’t sound so bad until one considers it in light of a second, more straightforward statement by Douglas Southall Freeman in R.E. Lee: A Biography (1934): “Occupying sixty-eight pages and containing nearly 34,000 words, from no point of view can it [Lee’s biography of his father] be accounted an effective piece of writing…. [When Lee] came to formal composition, most of the grace and all the spontaneity of his style [in his letters] disappeared. What he wrote became ponderous and dull.”7

1885

Grant published the first of his two-volume Personal Memoirs, finished 15 years after Lee’s death and just three days before Grant himself died. Immediately noteworthy is Grant’s title, surely the suggestion of his publisher, Mark Twain. The title shows that a new kind of memoir was emerging. It would not only be written by the memoirist himself, it would be about him. Although Confederate lieutenant general Richard Taylor used “personal” in the subtitle of his memoir Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War (1879), Grant’s memoir moved the word into its main title. Twain used it again in 1888, for Personal Memoirs of Philip H. Sheridan and two years after that, in 1890, when his New York firm, Webster and Company, published a third edition of Sherman’s memoirs titled Personal Memoirs of Gen’l. W.T. Sherman.

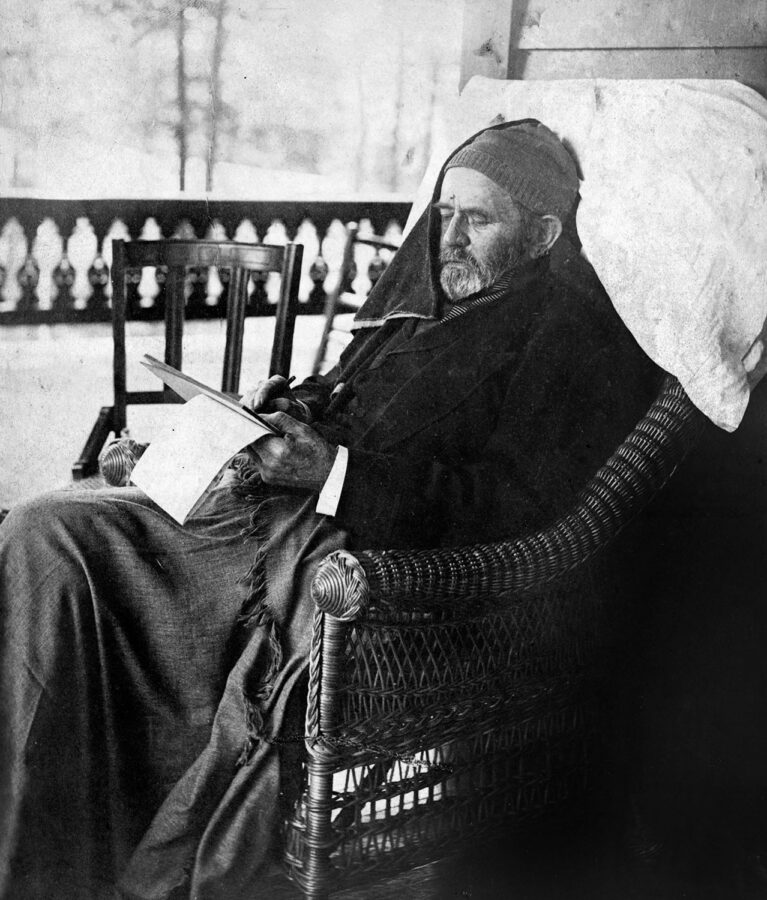

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAn ailing Ulysses S. Grant is shown writing his memoirs in this image made in June 1885, a month before he succumbed to cancer at 63. Grant’s work represented a new kind of memoir—one written by, and about, the memoirist himself.

To underscore that the writer was going to get personal with the reader, Grant began the first sentence of this first volume in the first person: “My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral.” By contrast, Lee’s biography of his father approached his genealogy from the third person: “The Lee family in Virginia is the younger branch of one of the oldest families in England.” Lee scrupulously avoided any personal touches throughout the biography.8

What made Grant’s book otherwise important was the convergence of first-person storytelling with the most extensive violence yet visited on people living in the United States. No one aware of that violence, suffered firsthand or witnessed from a distance, could comprehend the whole of it; each could know it only from an individual point of view. Grant’s and other generals’ memoirs of the 1870s and 1880s proved especially effective in the Civil War memory market because of their innovative application of the personal to the impersonal, of private sensibility to public events. Twain knew the 19th-century reading public, he knew the Civil War memory market, and he knew that public reading tastes had been shaped by increasingly sophisticated first-person combinations of materials into new imaginative wholes.

Lee scrupulously avoided any personal touches throughout the biography [of his father].

During the 1830s and 1840s, readers became familiar with Edgar Allan Poe’s first-person narrators, many of them extravagantly unreliable. In 1847 came Charlotte Bronte’s groundbreaking narrative experiment, Jane Eyre. The years 1849–1850 and 1860–1861 brought the serialization of two first-person masterworks by Charles Dickens: David Copperfield, which Grant read, and Great Expectations, which Sherman was rereading the day he died. By 1865 more than a hundred slave narratives had appeared in North America, over half of them in the 1840s and 1850s, and many of these narratives employed a first-person voice. And by the time that many American readers came to read Civil War generals’ memoirs, they had before them the greatest experiment in first-person colloquial narrative the country had yet produced, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884).

Twain, the showman and literary P.T. Barnum of publicity, was gambling that what the reading public wanted was not Robert E. Lee-style British 18th-century prose, ponderous and dull, with its dignified and impersonal veneer, its clothing of even common things in lofty phraseology. Readers wanted someone speaking directly to them, in their own vernacular idiom, about the national convulsion they had just been through. What’s more, whereas Lee’s prose about his father was humorless, Grant offered examples of dry wit, self-mockery, and wry understatement in the style of Lincoln.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressMark Twain in 1896

Blockbuster sales of Grant’s book confirmed Twain’s intuition. Eventually Twain paid Grant’s widow, Julia Dent Grant, the equivalent in today’s dollars of between $10 million and $11 million. Because Twain agreed to give Grant royalties of 70 percent, the book must have earned what would be between $14 million and $15 million in today’s dollars.

This was a watershed moment in the history of American memoir. Grant’s book, and Twain’s marketing of it, established a new precedent: Americans wanted to read the personal recollections of famous people who talk about themselves and they made it lucrative for memoirists. Type “memoir” into the Amazon search bar and it returns over 100,000 results. Type “memoir” into the search bar of WorldCat, the most comprehensive database of library collections, and the results exceed 1 million.

Most of those authors have not read Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant nor do they realize that the U.S. market for their wares took off with Grant’s book. There is no question that since the late 19th century other tributaries have been flowing into the changeable course of first-person memory narratives. The 20th-century rise of psychotherapy has played a significant role, as have 21st-century technologies designed to exhibit and disseminate people’s own words and images. One does not have to be a leading actor in public affairs or public service—or to be even “public” beforehand—to command an audience of hundreds, thousands, even millions.

At the same time, it has become increasingly commonplace for all those personalities to proceed directly to lucrative contracts for their memoirs. This path—amid and after events described and interpreted in the memoirs of their leading actors—was smoothed by the proliferation of Civil War memory over the last decades of the 19th century. And the evidence we have suggests that Robert E. Lee—perhaps intimidated by historical and literary standards, or worried about too-great expectations, or fearful of diminishing his warrior legend—could not bring himself to enter that procession.

Stephen Cushman’s recent books are The Generals’ Civil War: What Their Memoirs Can Teach Us Today (UNC, 2021) and, co-edited with Gary W. Gallagher, Civil War Witnesses and Their Books: New Perspectives on Iconic Works (LSU, 2021). Cushman serves on the executive council of the NAU Center for Civil War History at the University of Virginia, where he is Robert C. Taylor Professor of English.

Notes

1. My thanks to Dr. Gordon Blaine Steffey, Director of Research and the Jessie Ball duPont Memorial Library, Stratford Hall Historic Preserve, for an invitation to present an early version of this essay as the Annual Lee Lecture, January 20, 2024.

2. Thomas M. Cook, “The Rebellion: Views of General Robert E. Lee,” New York Herald, April 29, 1865. “Mr. Thomas M. Cook’s Despatch” was dated April 24, 1865. This issue of the New York Herald should not be confused with that of the New York Weekly Herald published the same day, which contained extensive coverage of “Obsequies to Abraham Lincoln,” including the funeral procession in New York, as well as coverage of Sherman’s negotiations with Johnston in North Carolina and the rejection of their agreement by President Andrew Johnson and his cabinet. For transcriptions of three postwar “conversations” with Lee, see Gary W. Gallagher, ed., Lee: The Soldier (Lincoln, 1996), 3–34.

3. James Gilreath and Douglas L. Wilson, eds, Thomas Jefferson’s Library: A Catalog with the Entries in His Own Order (Washington, D.C., 1989), ix.

4. Robert E. Lee to John Livingston, October 20, 1854, Stratford Hall Historic Preserve Lee Family Digital Archive, leefamilyarchive.org/history-papers-letters-transcripts-wp-wp469/ (retrieved May 21, 2024).

5. Charles Benjamin Richardson to Robert E. Lee, May 5, 1865, Stratford Hall Historic Preserve Lee Family Digital Archive, leefamilyarchive.org/charles-benjamin-richardson-to-robert-e-lee-1865-may-5/ (retrieved May 23, 2024).

6. Allen W. Moger, “General Lee’s Unwritten ‘History of the Army of Northern Virginia,’” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 71, 3 (July 1963): 341–363; Robert E. Lee to Charles Carter Lee, August 18, 1865, Stratford Hall Historic Preserve Lee Family Digital Archive, leefamilyarchive.org/history-papers-letters-transcripts-wl-w232/ (retrieved May 23, 2024).

7. Bradford’s sentence appeared first in Gamaliel Bradford Jr., “The Spiritual Life of Robert E. Lee,” The Atlantic Monthly (October 1, 1911): 501, then in Lee the American (Boston, 1912), 221–222. For Freeman’s comments, see Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee, a Biography, 4 vols. (New York, 1934), 4:417.

8. Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, 2 vols. (New York, 1885-1886), 1:17; Henry Lee, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States, new rev. ed. with biography of the author by Robert E. Lee (New York, 1869), 11.

Related topics: Confederacy, Robert E. Lee