National Postal Museum

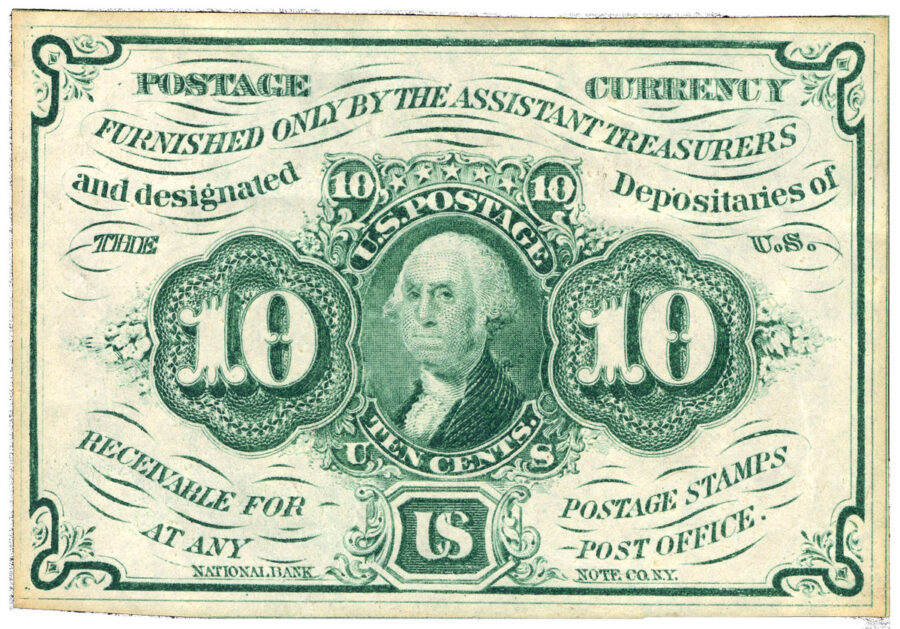

National Postal MuseumAn example of “postal currency,” which, like “postage stamps,” were used during the Civil War in lieu of gold and silver coins.

Postal Currency | noun | Postage-stamps in circulation as currency during the early part of the late civil war. See Stamps.1

Stamps | noun | Bank-notes, greenbacks, or any other paper money. Perhaps from postage-stamps, which were used as money in 1861-62. See Postal Currency.2

Published in 1877, the updated edition of John Russell Bartlett’s Dictionary of Americanisms recognized notable linguistic changes wrought by the American Civil War. “During the eighteen years that have passed since the last revision [in 1859 and 1860], the vocabulary of our colloquial language has had large additions,” he wrote. “The late civil war has given rise to many singular words.

Some of these, in common use among our soldiers during the late war, have since been dropped. Others have not only been preserved in our colloquial dialect, but have been transplanted to and adopted in foreign countries where the England language is spoken.”3 Some additions included: contraband, bummer, copperhead, confederates, carpet-bagger, jayhawker, and skedaddle. Four new terms, in particular, related to the evolution of American currency: greenbacks, soft money, stamps, and postal currency.4

Uncertain times often generate shortages. In 2020, Americans hoarded toilet paper in the face of a pandemic that confined them to their homes. When the Civil War commenced, Americans stockpiled provisions to prepare for impending hardships and shortages. By early 1862, millions of dollars in gold and silver coins had disappeared from circulation.

In the North, the United States Mint in Philadelphia began issuing copper-nickel coins, but demand outpaced supply.5 Without access to federally minted coins, Americans conducted their daily business with an assortment of legitimate and illegitimate currencies: state bank notes, shinplaster (a piece of privately issued paper currency), counterfeits, metal tokens, credit, bartering, and other innovative alternatives. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported, “treasury demand notes, bank notes and credits, without regard to specie reserves, good-looking counterfeit notes, bad-looking shinplasters, worthless promises, undeveloped stump-tail, anything that public credulity consents to circulate, is, for the time, a perfect medium of exchange.”6

The United States banking system was ill-prepared for war, and government officials were troubled by the conflict’s mounting financial burden, lack of species, proliferation of illegitimate currencies, and commodity inflation. In the summer of 1861, the United States government authorized the borrowing of $250 million to finance the war and issued bonds payable in 20 years, and it also printed a series of “demand notes,” consisting of $5, $10, and $20 notes intended for circulation.

In an effort to maintain the hard-money doctrine, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase met with bankers in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia to obtain $150 million in government securities; he insisted they pay for bonds in species. Americans, in turn, flocked to the banks and presented their newly issued demand notes in exchange for hard money, causing gold and silver coins to flow into the hands of citizens and speculators. Neither the government nor banks managed to accumulate coins, and the banks suspended all specie payments on their notes in December 1861.7 The currency problem had not been resolved.

Examples of “postal currency,” which, like “postage stamps,” were used during the Civil War in lieu of gold and silver coins. National Postal Museum

National Postal Museum

Although not considered legal tender, postage stamps—with a definite value of less than $1 printed on their front—entered into circulation in 1861 as a means of exchanging small denominations. Postage stamps were a relatively new concept. In the nation’s early years, mail often went missing and letters traveled postage due; to claim a letter the recipient paid a fee based on the weight and distance traveled.

In 1847, Congress authorized the development of prepaid postage stamps, and the first batch of adhesive stamps went on sale that summer in New York. The 5-cent stamp featured Ben Franklin, the nation’s first postmaster general, and the 10-cent stamp depicted George Washington. Prepaid stamps were initially unpopular with consumers, and it took until 1855 for Congress to make the use of stamps compulsory.8

When war broke out in 1861, Americans had been using postage stamps for only six years. Yet, in the absence of gold and silver coins, postage stamps emerged as a means of exchange for small transactions under a dollar. “When the Post Office sells postage stamps for money it promises to render a service in exchange for the money…. Every one has occasion to send letter by post, and therefore they are willing to receive postage stamps instead of small amounts of money,” observed a Scottish economist.9 In New York, the Central Railroad, New Bowery Theatre, Niblo’s Garden, and Francis Duffy’s Oyster and Dining Saloon, all issued change to wartime customers in envelopes containing various postage stamps.10

Postage stamps proved inadequate as currency. As Scottish-born author and publisher John Phin noted in Common Sense Currency, his 1894 book on the American financial system, “As may well be supposed, gummed postage stamps were not a very convenient medium of exchange; they easily became soiled and defaced, and besides this, they stuck to each other and to everything else.”11

On a stormy winter night, a patron attempted to pay his six cent Broadway stagecoach fare only to have the stamp “stick to his wet woolen gloves” or fall and get “lost in the straw on the floor.”12 Another consumer complained, “the present currency, if carried losse [sic] in the pockets upon a warm day, when taken out resembles in appearance a spit-ball rolled in the gutter.”13

The Post Office, in turn, refused to accept soiled stamps for mailing letters.14 As Phin noted, people soon devised contraptions for carrying large quantities of stamps, “some of these were mere envelopes made of transparent papers, through which the stamps could be seen and counted, thus avoiding all necessity for handling them. The favorite form consisted of a case of thin sheet brass in which the stamp was enclosed and the face covered with mica, or isinglass.”15

In August 1862, New Yorker John Gault received a patent for his “Design for Encasing Government Stamps.” Resembling a coin, this new device encased a single postage stamp inside a round silver or brass cover. To increase his profit margin, the entrepreneurial Gault printed advertisements on the back of stamp cases for approximately thirty northern businesses, including J.C. Ayer & Company’s “Sarsaparilla To Purify the Blood.” About $50,000 in encased postage stamps circulated during the Civil War.16

In February 1862, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, which authorized $50 million in new demand notes and $100 million in new legal tender notes, which were printed on the reverse with green ink. This new national currency was not tied to specific government specie reserves and was guaranteed to be accepted for “all debts Public and Private except, Duties on Imports and Interest on the Public Debt, and … exchangeable for U.S. Six per cent Twenty Year Bonds, redeemable at the pleasure of the U. States after Five Years.”17

The issuing of greenbacks commenced with $5 notes, and soon added $1 and $2 notes. Greenbacks entered into widespread circulation in 1862, but that failed to resolve the coin shortage. A “desperate” man contacted an editor at The New York Times requesting that the government issue new bills in $1.10, $1.20, $1.25, $1.30, $1.40, $1.50, $1.60, $1.70, $1.75, $1.80, and $1.90 increments. “Wife complains terribly,” he wrote. “A $5 bill is good for nothing, unless a dollar’s worth is wanted. What’s a poor fellow to do, that has got no credit at the grocer’s?”18

In July 1862, Congress passed legislation that prohibited the circulation of shinplaster from private corporations, banks, and individuals in amounts under one dollar, and also authorized the Treasury Department to make “postage and other stamps” exchangeable for United States notes and accepted for payment for dues less than $5. The vaguely worded Stamp Payments Act did not expressly authorize the circulation of postage stamps as legal tender, but rather authorized the government to print new postal currency in 5-, 10-, 25-, and 50-cent denominations.19

Clarifying the distinction between postal stamps and postal currency, New York City’s postmaster Abram Wakeman explained: “‘Postage stamps’ have been and are very generally confounded with ‘postage currency.’ This error has been the cause of misapprehensions and difficulties…. ‘Postage currency’ is issued only by the Secretary of the Treasury or his Assistants pursuant to the act of Congress approved July 17, 1862, and cannot be used for prepayment of postage, . . . and was intended to be used for the purchase of ‘postage stamps’ and as currency.” He continued, “‘Postage stamps’ cannot be used as currency without diverting them from the purpose for which they were designed, and violating the orders of the Post-office Department. To use them as such is to wrest them from their proper office, and apply them to a purpose for which they were not designed. or adapted.”20

Featuring postal iconography, the new postal currency omitted the adhesive backing and was printed on paper “forty times stronger than … now used. It can be washed like a piece of linen, without in any way injuring the engraving and withal it cannot be photographed, as it photographs, a dark brown instead of white like ordinary paper.”21

Problems arose immediately. Printing commenced in August 1862, but the National Bank Note Company experienced numerous delays, resulting in a shortage of the new currency. Consumers failed to distinguish between postal stamps and postal currency, and merchants abhorred the adhesive-backed stamps and preferred shinplaster. The stamps also proved remarkably easy to counterfeit, and, as The New York Times noted, “probably there is not a town of twenty thousand inhabitants in the Union that cannot turn out an engraver who can duplicate the plate of any Postage Currency note now in circulation.”22

After mere months in circulation, fractional currency replaced postal currency in the spring of 1863. For the remainder of the war, the United States government continued to refine its monetary policy, and the National Currency Act of 1863 and National Bank Acts of 1864, 1865, and 1866 resulted in the gradual development of a new and uniform system of nationally chartered banks. The Civil War transformed American currency. In the end, postage stamps and postal currency were just steps in the nation’s journey toward a monetary system based on a uniform currency.

Tracy L. Barnett is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia. Her dissertation analyzes the historical origins of America’s gun culture and its mutually constitutive relationship to white supremacist ideology. She teaches history at Loyola University Maryland.

Notes

1. John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States, Fourth Edition (Boston, 1877), 486.

2. Ibid., 654.

3. Ibid., III, VI.

4. John Russell Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms: A Glossary of Words and Phrases Usually Regarded as Peculiar to the United States, Third Edition (Boston, 1860); Bartlett, Dictionary of Americanisms, Fourth Edition, 263, 486, 624, 654.

5. “Repudiation of Postage Stamps,” The New York Times, November 14, 1862; James E. Kloetzel, “Encased Postage Stamps,” Smithsonian National Postage Museum.

6. Chicago Daily Tribune, September 5, 1861, as quoted in Joshua R. Greenberg, Bank Notes and Shinplasters: The Rage for Paper Money in the Early Republic (Philadelphia, 2020), 163.

7. Stephen Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters: Capitalists, Con Men, and the Making of the United States (Cambridge, 2009), 310–311.

8. John F. Ross, “Stamps, What an Idea!” Smithsonian Magazine (January 1998).

9. Henry Dunning Macleod, The Theory and Practice of Banking, Vol. 1, Third Edition (London, 1875), 19.

10. Thomas Cunningham, “Postal and Fractional Currency,” American Journal of Numismatics, and Bulletin of the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society, Vol. 27, No. 4 (April 1893): 75; Henry Russell Drowne, “U.S. Postage Stamps as Necessity War Money,” The Numismatist, Vol. 33, No. 5 (May 1920): 182–186.

11. John Phin, Common Sense Currency: A Practical Treatise on Money in Its Relations to National Wealth and Prosperity (New York, 1894), 137.

12. Drowne, “U.S. Postage Stamps as Necessity War Money,” 181.

13. The Daily Register (Wheeling, WV), September 18, 1863.

14. “Postage Stamps as Currency,” The New York Times, October 4, 1862.

15. Phin, Common Sense Currency, 137–138.

16. James E. Kloetzel, “Encased Postage Stamps,” Smithsonian, National Postage Museum.

17. Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters, 315, 318; Joshua R. Greenberg, Bank Notes and Shinplasters: The Rage for Paper Money in the Early Republic (Philadelphia, 2020), 163.

18. “The Danger of Shinplasters,” The New York Times, July 13, 1862.

19. Greenberg, Bank Notes and Shinplasters, 162–165.

20. “The Postage Stamp Currency,” The New York Times, October 11, 1862.

21. The Daily Register (Wheeling, WV), September 18, 1863.

22. “Counterfeit Postal Currency,” The New York Times, December 22, 1862.