CWM Collection

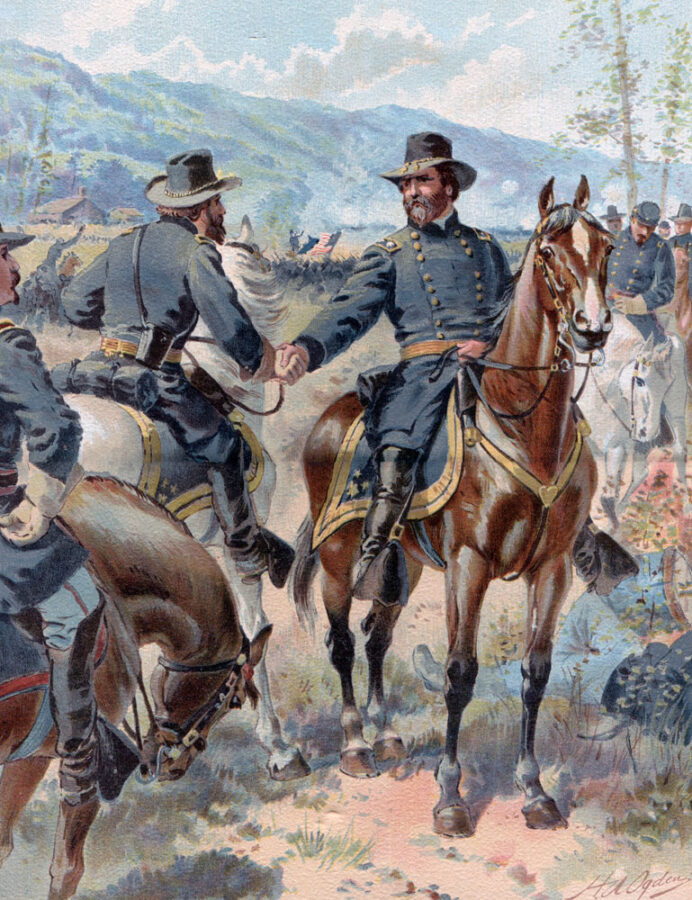

CWM CollectionIn this postwar illustration by Henry Alexander Ogden, Union general George H. Thomas is shown riding the field during the Battle of Chickamauga. While his quick thinking during that engagement earned Thomas praise, a decision by Union officers John Mendenhall and Thomas Crittenden tarnished Crittenden’s reputation, though he challenged the criticism.

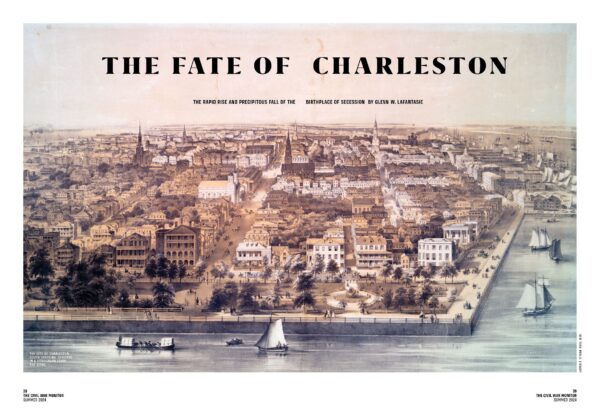

At a little past noon on September 20, 1863, the Union Army of the Cumberland was in crisis. In its third day of fighting in the woods and fields near Chickamauga Creek in northwest Georgia, Major General William S. Rosecrans’ men had managed to withstand the battering of General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, despite the Confederates’ strenuous efforts to outflank them. The objective of the battle and its accompanying campaign was the strategically critical city of Chattanooga.

The stubborn Federals had done well so far, managing to withstand vigorous but disjointed attacks all along the left of their strong defensive position. While Bragg had not succeeded in turning the Union flank that morning, Major General George H. Thomas, the officer overseeing the sector, was understandably concerned. Thomas repeatedly asked Rosecrans for reinforcements and support throughout the morning; Rosecrans, worn out and overstressed by his exertions, misinterpreted Thomas’ requests and assumed that a gap had somehow been opened in his army’s line. No such gap existed.1

Rosecrans then committed a serious error by ordering Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood’s division out of its position near the Federal center to plug this imaginary hole. Wood received Rosecrans’ order at around 10:40 a.m., and began his withdrawal at about 11 a.m., creating a division-sized gap in the Federal defenses. Coincidentally, a massive assault by Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s corps stepped off at 11:10 a.m. and struck this new gap at the precise time and place the Federals were most vulnerable. Their line shattered under the force of the attack, and a major part of the Army of the Cumberland began to rout. As Longstreet’s attack split the Union forces in two, Bushrod Johnson’s division pivoted north, seeking enemy targets; the Confederates soon found a tantalizing objective on a ridge overlooking the fields belonging to the Dyer family, behind the Federal left.

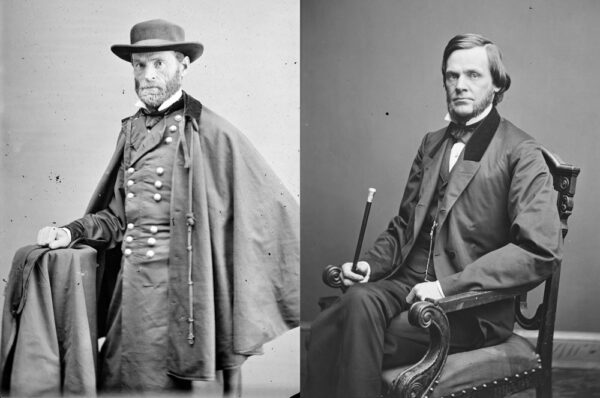

Major John R. Mendenhall, chief of artillery for Major General Thomas L. Crittenden’s XXI Corps, consulted with his boss about where and how to best make use of his guns. The day before, other commands had scooped units from the XXI corps as Rosecrans and Thomas cobbled together a defensive effort against determined Confederate pressure. The densely wooded battlefield was not the best landscape for artillery, and several Union batteries had been lost during the confused close-quarter firefights that day. Mindful of this problem and hoping to employ their guns in a more effective manner, Crittenden and Mendenhall made an important decision. Crittenden had Mendenhall gather any available artillery and post them along the ridge near the Dyer property, which provided a commanding slope and clear fields of fire to their front. It seemed a good position, and, as Crittenden would later report, would allow the guns to “cover our retreat” in “the event of any reverse” that might befall the Union army.2

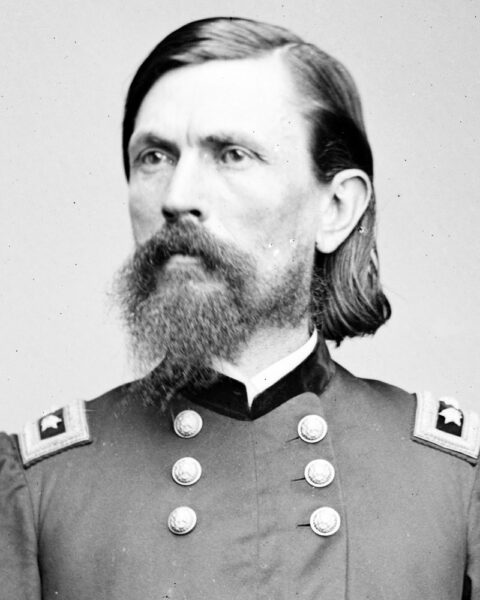

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThomas Crittenden

Tactically, however, the Dyer ridge position had fatal problems. The clear fields of fire forward of the proposed gun line afforded a spectacular view that terminated in lines of timber. Any Confederate attack would need to pass through those trees in order to reach Mendenhall’s guns. But the distance across the Dyer fields from the cover of the tree line was barely 400 yards, which was not nearly enough to permit even seasoned Union gunners the time needed to repulse a determined enemy assault—at least not without infantry support to protect the gun crews.

It is unclear whether Mendenhall and Crittenden disagreed at any point in their planning. Certainly Mendenhall, a young major, would have found it politically difficult to raise any serious objection with Crittenden, a corps commander. Moreover, time was of the essence as the Confederate breakthrough had unleashed the start of an unfolding disaster. Both officers understood the situation was dire, and with the decision made, Mendenhall leapt into action.

Throwing any available piece and crew into the line, Mendenhall personally assembled a formidable row of 26 guns. Among them was Captain Alanson J. Stevens’ 26th Pennsylvania battery (notably, Stevens was the nephew of the famous Radical Republican U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens). As Mendenhall rode to and fro marshaling batteries, Crittenden tried to scrape together whatever infantry he could find. Mendenhall and his makeshift gun line watched for about an hour as the ominous roar of the approaching storm echoed through the woods beyond the Dyer field. Behind them, thick timber and a rocky drop led to a road that might promise an avenue of retreat to the fortifications of Chattanooga.

Unfortunately, the Federal gunners would have to negotiate tangled thickets and trees to get there—all without benefit of infantry support to cover their possible escape. A few infantry units took up defensive spots on the slope, but they were not enough to reassure the nervous Federal gunners. For the moment, Mendenhall could only wait and hope that the decision to make a stand would not prove disastrous. It was a vain hope. A strong force of multiple Confederate brigades, flush from their exhilarating breakthrough, burst through the woods to Mendenhall’s front and rushed the Federal gun line.

The artillerists let loose with a deafening barrage, and for a time, it looked as if the devastating fire from the Union guns might stem the tide. As the gunners pounded the Confederate formations crossing the Dyer fields, additional Rebel brigades began sweeping around both flanks of Mendenhall’s vulnerable position. Soon they found their position outflanked and, eventually, nearly encircled, and Mendenhall’s batteries began to fall. Horses and men were hit, and crews tried desperately to pull back into the woods. Canister and bullets raked the gunners, and many crews simply abandoned their pieces rather than be slaughtered by the exultant Confederates.3 In the end, the Rebels captured 14 of the 26 pieces in Mendenhall’s force.4

Crittenden’s reputation did not long survive the debacle, partly because of his reaction to the disaster. The corps commander was not with Mendenhall and the guns when Confederates overran the position; he was still attempting to gather infantry to reinforce the line. When his position disintegrated, he had virtually no troops left in his charge. Those who remained in fighting condition had been divvied up among other commands and were fighting desperately in other actions. Crittenden waited for some time, as stragglers fled the area ahead of the Confederate attack, until he finally declared to his staff, “I believe I have done all I can.” Rosecrans’ headquarters had also been overrun; the general had already departed the battlefield for Chattanooga, and Crittenden was at a loss for what to do next. He turned to the staffers and asked, “Can any of you make a suggestion?” One staffer suggested that Crittenden’s reputation would suffer if he quit the field, and that the best course might be to report to Thomas, the senior general still remaining. Crittenden demurred, electing instead to join Rosecrans in Chattanooga.5

Crittenden would go on to be relieved of command of the XXI Corps, and though he was later exonerated of blame for the rout at Chickamauga, he had lost the confidence of his superiors in the West. Mendenhall, on the other hand, received praise for his desperate stand and continued to serve as an artillery commander until the end of the war. Responsibility ultimately rests with the leader in charge, and Crittenden was that leader.

Although the officers’ decision to form a gun line and attempt to stem the tide of the Confederate breakthrough was a bold one, it was also born of desperation. Decisions in war are often made under intense pressure, with incomplete information, imperfect circumstances, and life-and-death stakes. In hindsight, the better choice would have been to attempt to salvage any units still intact after the Confederate breakthrough and send them to the aid of Thomas, fighting on the far left of the Union line, or instead, put them on the road north to Chattanooga. Errors and miscalculations such as this do not always become legible until after days, months, or even years of close study. But there is always wisdom to glean from examining the decisions that contribute to defeat or failure.

Andrew S. Bledsoe is associate professor of history at Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. He is the author of Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (Louisiana State University Press, 2015); co-editor, with Andrew F. Lang, of Upon the Field of Battle: Essays on the Military History of America’s Civil War (LSU Press, 2019); and author of the recently released Decisions at Franklin: The Nineteen Critical Decisions That Defined the Battle (University of Tennessee Press).

Notes

1. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records 129 vols. (Washington, 1880–1901), Series I, vol. 30, pt. 1, 635 (hereafter OR).

2. OR, Series 1, vol. 30, pt. 1, 609–610.

3. Ibid., 800, 977, 984.

4. Ibid., pt. 2, 497–498. Post-battle disputes among Confederates varied between 9 and 15 guns captured. Historian David Powell places the most reliable figure at 14 guns. David A. Powell, The Chickamauga Campaign: Glory or the Grave (El Dorado Hills, CA, 2015), 346–347, n. 41.

5. OR, Series 1, vol. 30, pt. 1, 984.