“It is the best one-volume treatment of its subject I have ever come across. It may actually be the best ever published. It is comprehensive yet succinct, scholarly without being pedantic, eloquent but unrhetorical. It is compellingly readable. I was swept away, feeling as if I had never heard the saga before. It is most welcome.” So wrote a reviewer in The New York Times about Princeton University history professor James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, shortly after the book’s 1988 release. Published by Oxford University Press as part of its Oxford History of the United States series, Battle Cry of Freedom was an instant—and huge—success. Despite its size (900-plus pages), scope (the first 233 are devoted to the burgeoning secession crisis between 1848–1860), and copious footnotes, McPherson’s scholarly narrative history was embraced by a popular audience, spending 16 weeks on The New York Times hardcover bestseller list (and later 12 weeks on the paperback list). It also garnered praise from fellow professional historians, winning the 1989 Pulitzer Prize in History. While McPherson’s distinguished career includes over 20 books on the Civil War era, many of them also earning critical acclaim and distinguished awards, Battle Cry of Freedom remains, especially in the popular mind, his greatest literary achievement. To mark Battle Cry’s 35th anniversary, we asked a few historians to weigh in on the book and its author. Their observations follow, along with remarks by McPherson, who currently serves as the George Henry Davis 1886 Professor of American History emeritus at Princeton.

The 35th Anniversary of Battle Cry of Freedom

By Jennifer L. Weber

Those 35 years went fast. And in the years since Oxford University Press published James M. McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, universities have granted Ph.Ds. to a couple of generations of historians, historians have done more research on the Civil War, and we learn more about the war all the time. Today, historians of the war are thinking more about the experiences of black men and women. We’re putting the American Civil War into a global context. We’re learning more about how the war played out in various communities, be they actual towns or something more imagined, such as political communities. And still, with all that new research, Battle Cry remains the single best book on the war. The reason for that is simple: It is both meticulously researched and incredibly well written. It is clear. It is straightforward. It is sometimes funny, as with McPherson’s wry observation about the hard-drinking Joe Hooker’s failure at Chancellorsville: “Perhaps his resolve three months earlier to go on the wagon had been a mistake, for he seemed at this moment to need some liquid courage.” Like its author, the book is utterly unpretentious. It is, in a word, accessible—again, just like its author.1

More than 25 years ago, I reached out to McPherson as I was working on a master’s degree. This was an after-hours hobby for me. During the day, I was a copy editor at The Sacramento Bee. I had a class that had two assignments: Write a historiography of a famous living historian’s works and write about a historiographical debate. McPherson fit the bill for both assignments. I had long been a fan of his work, and I’d also read an article of his in which he made the case for a more narrative voice in writing history. As I recall, he said that the narrative and analysis did not have to be mutually exclusive. I called McPherson and left a message on his phone at Princeton University. A couple of days later he called me back and we spent an hour and a half talking about his scholarly progression from African-American historian to Civil War historian, and his thoughts on writing. What was remarkable was that this man—arguably the most famous historian in America at the time and still the dean of Civil War specialists—spent that much time with an interested and informed person whom he had never met.

A couple of years after that phone call, I went to Princeton to earn my doctorate under McPherson’s mentorship. What I quickly learned is that my conversation with him was not an outlier. I often walked into his office while he was on the phone with the Washington Post, say, or CNN. He sat with any number of documentary makers to share his insights and his ideas. He used his powers to keep the Walt Disney Company from building a history-based theme park (plus homes, hotels, and retail and commercial centers) near the site of the first Civil War battlefield at Manassas, Virginia. McPherson’s argument at the time was that the park could “not only destroy important Civil War sites but would trivialize and sanitize American history,” according to The New York Times. He returned every call and responded to every piece of mail, whether the writer was a 10-year-old looking for information about the war or a random adult interested in talking with him about history and the narrative form. This changed only in the early aughts, after he said something publicly about the problematic nature of the Confederate battle flag. He received hundreds of postcards torn out of the magazines of Confederate heritage groups objecting to his statement. They showed up in his mailbox each day, stacks of them tightly bundled together with rubber bands. He could not begin to respond to the deluge. But it did not make him change his mind.2

Meanwhile, McPherson was also conducting tours of Civil War sites. Some of these were in conjunction with various paid tour organizations, but most of them were for his friends or Princeton students and alumni. Every April, for instance, he took his Civil War class to Gettysburg. The trip became such a hot ticket that not only his students came, but so did their friends, roommates, and parents. Between 200 and 300 people would decamp from Princeton at the ungodly hour of 7 a.m. After covering the first day of the battle, the group had lunch. No breaks after that. By the time McPherson reached the end of the tour in the cemetery at twilight, the group had dwindled to a couple of dozen. Those college students could not keep pace with him.

In all these ways, McPherson very quietly became a sort of Pied Piper for the historical profession. He has long reached beyond the ivy-covered walls to speak to regular Americans and teach them about their history, good and bad. His colleagues were largely unaware of his grass-roots activities, but McPherson has made history interesting and relevant for several generations of Americans now. Battle Cry, which won the Pulitzer Prize, is the most notable of McPherson’s books, at least to the general public. But his greatest legacy is in his outreach efforts: He hasn’t taught just students at Princeton. He has taught us all.

Jennifer L. Weber is an associate professor of history at the United State Air Force Academy. The views expressed in Jennifer L. Weber’s essay do not necessarily represent those of the United States Air Force Academy, the United States Air Force, or the Department of Defense.

McPherson’s Many Meanings of Freedom

By Matthew E. Stanley

Calls for “freedom”—so ubiquitous in American history and political discourse—require a series of modifiers: Freedom of what? Freedom from what? Freedom to do what? Freedom for whom?

James M. McPherson’s 1988 classic Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era is a magisterial tome that seamlessly blends social, political, economic, and military history. The result is arguably the best single-volume treatment of the coming of the Civil War and the conflict itself. It is a monumental and wide-ranging piece of scholarship.

And despite its breadth and sophistication, a central theme emerges: the multivocal and contested nature of freedom, a word from the title that appears 98 times in the narrative. Accounting for both negative (freedom from) and positive (freedom to) definitions, McPherson’s opus details how a shifting antebellum economy engendered sectionalism, social reform, and party cleavages that delineated and changed how freedom was understood. McPherson begins the book’s preface, “Both sides in the American Civil War professed to be fighting for freedom.”

Yet Battle Cry of Freedom soon reveals that there were more than “two sides” and more than two meanings of freedom. In fact, freedom during the “Middle Period” of American history was not only sectionalized, but also racialized, classed, gendered, and regionalized, splitting both along and within party lines. During the 1830s and 1840s, Whigs found freedom in tariffs, internal improvements, and market dynamism; Democrats, conversely, worried that the pace of economic transformation and concomitant concentrations of both state and corporate power would upend “free” republicanism. And while reformers identified freedom in women’s rights, public schools, Protestant missionizing, temperance, and, above all, opposition to slavery, anti-reformers, whether Catholic immigrants or Jacksonian yeomanry, espoused the “freedom to live as they pleased.”

As class lines sharpened, northern owners increasingly viewed freedom as an unregulated wage labor system, with the right to pay workers as little, work them as long, and monopolize as many resources and profits as possible. At the same time, to a growing class of workers—“wage slaves” free to sell their surplus labor or starve—to be free called for autonomy and non-domination in the workplace, along with greater equalization of property.

By the 1850s a “free labor” ideology had emerged in the non-slave states. Institutionalized within the nascent Republican Party, or what Massachusetts politician Charles Sumner had hoped for as “one grand Northern party of Freedom,” it resulted in a cross-class and (in places) interracial electoral coalition. The new, hybridized Republican definition of freedom included open immigration, free land to surplus workers (which required further losses of freedom for Indigenous populations), and a chimerical escape from the wage system through upward mobility within an expanding and increasingly capricious capitalist order. Most importantly, its version of freedom was predicated on the absence of competition with slave labor.

Unsurprisingly, understandings of freedom shifted dramatically based on nearness to the plantation heartlands. To slaveholders and those who aspired to slave ownership, freedom was a condition created by the slave system. Formulations of “white liberty,” which McPherson describes as “Orwellian” in their authoritarianism, denoted a small white elite lording over both propertyless whites and an enslaved black labor force. It included not only ownership and absolute control over enslaved people, but also the free movement of slave property into U.S. territories and the perpetual growth of slavery’s empire through state expansion. As such, slavers championed the freedom to possess human property unencumbered by federal control (unless, of course, the capacity of the central state could be harnessed in their economic interests, as it often was). These contradictions led British radical John Bright to proclaim slaveholders “the worst foes of freedom that the world has ever seen.”

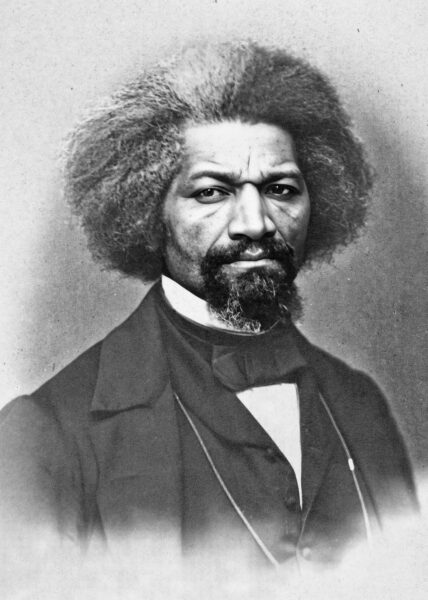

Notions of freedom for enslaved people, meanwhile, were immediate and concrete. They sought freedom when and where they could, finding glimmers of it in cultural and labor autonomy, as well as in acts of resistance. Fugitive slaves “stole” their own bodies and risked their lives in pursuit of freedom. Others achieved it through freedom suits, or the process by which enslaved plaintiffs sued for their freedom in court by claiming wrongful enslavement.

As McPherson makes clear, by 1860 freedom had become fatally binary. Despite its definitional diversity according to ethno-religious difference, reform orientation, and partisan affiliation, most white northerners by the time of the war took freedom to mean, on a basic level, political democracy (for some) and the preservation of the government. Through secession, white southern elites, who portrayed themselves as “slaves” of “Yankee rule,” espoused non-submission to “Black Republicans” and the freedom to leave the Union.

Yet McPherson suggests that even in a consensus-forging wartime climate, the sectionalization of freedom was far from total. Southern Unionists found freedom to be incompatible with a domineering Confederate state and resisted accordingly. Farther north, many border people saw freedom in the hope for sectional compromise. Anti-war Copperheads accused the Lincoln government of violating freedoms of speech and the press and the “natural” racial order. Articulating this sense of white grievance, Democrat and Copperhead leader Clement Vallandigham denounced the war as one “for the freedom of the blacks and the enslavement of the whites.”

Abolitionists held a sharply contrasting perspective. Advocating a “radical revolution” against slavery, they viewed emancipation, hard war, and material redistribution as necessary to, in the words of Republican congressman Thaddeus Stevens, “preserve this temple of freedom.” In time, the exigencies of war led the northern public toward a notion of freedom predicated on slavery’s destruction, or the idea that, as Lincoln phrased it, “freedom to the slave” would “assure freedom to the free.”

Yet to many white northerners this “new birth of freedom” for black people meant the freedom to work for wages and nothing else, or what former Union general (and future president) James Garfield denounced as “the bare privilege of not being chained.” “If this is the definition [of freedom] which the administration and people prefer,” observed one radical newspaper, “we have got to go through a longer and severer struggle than ever.”

Conversely, newly emancipated people yearned for a liberation based on civil rights, education, and land ownership. Their aspirations were more overtly bound to state policy by way of the Confiscation Acts, the Emancipation Proclamation, and Union military victories (and later the Freedmen’s Bureau and hopes for federal land redistribution). As abolitionist Wendell Phillips predicted, any postwar program that failed to break up large plantations and reallocate land and political power would “make the negro’s freedom a mere sham.”

Indeed, if McPherson successfully elucidates “what freedom(s) meant,” then the experiences of freedpeople illustrate how freedom was made tangible, and their freedom dreams—too often vacated—reveal how it could have been rendered even more substantial.

Overall, McPherson’s study of a conflict in which “all sides claimed liberty” illuminates how a shared political language of “freedom”—or of “democracy,” “justice,” and “equality,” for that matter—can yield so many divergent and, at times, diametrically opposed, interpretations. In that sense, Battle Cry of Freedom’s enduring popularity—35 years after its publication—stands as a testament not only to its unsurpassed craftsmanship, but also to the continued relevance of its themes, including “freedom” and its many meanings.

Matthew E. Stanley is an associate professor of history at the University of Arkansas.

Battle Cry as Military History

By Joseph T. Glatthaar

Since early in the 20th century there has existed a stark division among Civil War scholars and enthusiasts on the subject of military history. Influenced by the Civil War Centennial and the Vietnam War, many scholars avoided the actual war, focusing on political, economic, social, cultural, racial, and, more recently, gender issues. They viewed military scholarship as a world in which pedestrian battle studies dominated. Scholars argued that these volumes focused on minor activities and movements, lacked originality, introduced new information on the outcome of the war that was largely inconsequential, and offered little advancement in our understanding of the human condition. Some critics even believed that studying military aspects of the war promoted war and violence. By contrast, Civil War military enthusiasts viewed academic scholarship as detached from the critical aspect of the era, the war itself. They believed that professional historians investigated topics in all sorts of areas but ignored the battlefield, and it, and the Civil War’s leaders, were the only aspects that intrigued these devotees.

In the original edition of Battle Cry of Freedom, James McPherson succeeded by marrying the two worlds. The book possesses an extraordinary breadth and depth in its coverage of the Civil War era. McPherson views military history broadly. With the war as the central and defining element of that time period, he skillfully manages to incorporate political, diplomatic, social, economic, cultural, racial, and gender issues in his narrative, while maintaining a strong focus on the more conventional aspects of the conflict. His coverage meets the interests and highest standards of academics while appealing to military enthusiasts. For that reason, it was a runaway bestseller.

Battle Cry of Freedom still stands as a masterpiece in military history writ large. New scholarship only buttresses McPherson’s argument that slaveholders drove the secession movement and therefore the war with a kind of preemptive strike. His early chapter entitled “Amateurs Go To War” brilliantly exposes the chaos and lack of physical, mental, and emotional preparedness on both sides. With far too few exceptions the leaders and participants exhibited shocking naivete, and McPherson sets the stage for the extraordinary transformation of soldiers and sailors as they adapted to the harsh realities of war. Later in the book he notes how the Union ratcheted up its war effort to crush resistance to Federal authority. Union troops confiscated property, including slaves, and destroyed or seized anything of military value. Yankee leaders then flexed their military muscle by checking Confederate armies and marching through the Rebel interior, breaking any resistance of Federal power.

McPherson’s ability to master all aspects of the conflict is truly impressive. He explores financing the war on the two sides and unravels a complex maze of monetary and fiscal policies and legislation so that those with a limited background in economics can understand the tremendous advantage the Union possessed in raising money to pay for the war. He generates some interesting statistics on combat casualties and disease that challenge long-held assumptions, helping to show that westerners North and South were not necessarily the superior soldiers that most people assumed. The Union troops from the northeast largely came from urban areas, where they were exposed to diseases and had developed some resistance to the medical maladies that plagued camp life. Rural troops died or were discharged at a higher rate from disease than their eastern counterparts. Nor were easterners disadvantaged as soldiers. The largest battles with the heaviest casualties came in the Virginia theater, where a disproportionate number of troops came from eastern states. As he works his way through the war, McPherson moves seamlessly from Federals to Confederates and gives fair treatment to the underdeveloped aspects of the war, such as the blue- and brown-water navies, the home front, and foreign policy.

An expert on abolitionism and black military service in the war, McPherson clearly articulated the impacts of emancipation and recruitment of black soldiers and workers. Initially, the destruction of slavery through the two Confiscation Acts and the enlistment of blacks in the Union army was a means to victory. President Abraham Lincoln wrote Major General Ulysses S. Grant that it worked “doubly,” taking from the Confederacy and adding to the Federal cause. It stripped southerners of property, and these Contrabands then contributed to the Union war effort in and out of uniform. The ancillary benefits were that it introduced a powerful emotional component as southerners’ greatest fear, the loss of control of their enslaved people, came to fruition, and at the same time it heightened an important motivation for Union enlistment to a wartime objective. Thus, the Union elevated this “means” to victory to an end goal of the war. The destruction of slavery removed the one great division between the United States and the Confederate States. Otherwise, the reunited sections would have fought the same political battles over and over again.

Since the publication of Battle Cry of Freedom, scholars and enthusiasts have nibbled around the edges of McPherson’s military presentation, but there have been no monumental changes. Amid the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan scholars began emphasizing guerrilla warfare, certainly a neglected area in Civil War literature. McPherson covers guerrillas, perhaps not as much as these scholars wish, but while the actions of such comparatively small numbers affected their victims, they had no demonstrative impact on the war’s outcome. Civil War authors have since expanded their studies on black soldiers and refugees, some of which are very impressive, but again with the effect of building upon McPherson’s work, not tearing it down.

The one aspect of Battle Cry of Freedom that McPherson would probably change is his explanations of Federal soldiers’ motivation, specifically their devotion to the Union. He long held a healthy respect for the force of abolitionism as a rallying cry among Federal volunteers. Yet reading the letters of naval officer Roswell H. Lamson, which McPherson and his late wife, Patricia, published in Lamson of the Gettysburg (1997), he realized that in the minds of northerners the Union was the basis for freedoms, equality, and economic opportunity under the Constitution. Secession nullified the concept of a more perfect union and threatened everything that came with it. In his later books What They Fought For, 1861–1865 (1994) and For Cause and Comrades (1997), McPherson rectified that shortcoming.

As I look back over the great authors and books on the Civil War, it saddens me to know how little students of that era read Allan Nevins, Bell Wiley, or David Donald, to mention just a few. Yet McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom has retained its stature. It is still the finest single volume on the Civil War era, including the military aspects of that defining event in American history. Rather than suffer challenges that sought to overturn its arguments, Battle Cry of Freedom serves today as yesterday as a platform for additional scholarship. And while subsequent editions have incorporated subtle changes and linked the book to more contemporary literature, the original volume has withstood the test of time brilliantly.

Joseph T. Glatthaar is Stephenson Distinguished Professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Battle Cry of Freedom and the Confederacy

By Gary W. Gallagher

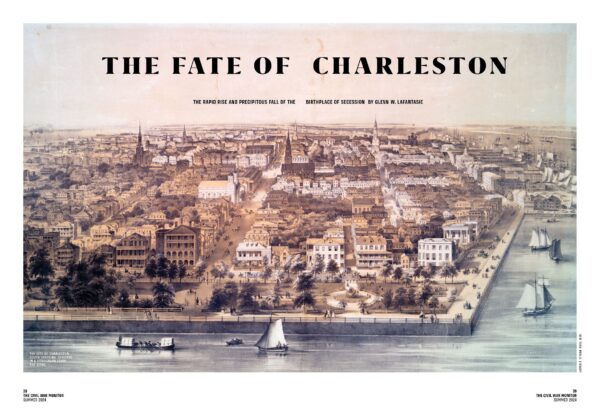

James M. McPherson crafted Battle Cry of Freedom as a detailed narrative that underscored the power of historical contingency. He focused most expansively, though not by any means exclusively, on political and military developments and countered the Lost Cause fiction that Union numbers and resources dictated the war’s outcome.3 In a text highlighting the unpredictable trajectory of unfolding events, McPherson insinuated analytical passages addressing the origins, progress, and demise of the Confederacy. For example, he left no doubt that “the fundamental issue of slavery” stood at the center of the sectional upheaval of 1860–1865. Although pro-secessionist rhetoric “bristled with references to rights, liberty, state sovereignty, honor, resistance to coercion, and identity with southern brothers,” both the lower and upper South “went to war to defend the freedom of white men to own slaves and to take them into the territories as they saw fit, lest these white men be enslaved by Black Republicans who threatened to deprive them of these liberties.”4

Military campaigns played so large a part in McPherson’s book that Oxford series editor C. Vann Woodward thought it necessary to anticipate complaints from those who marginalized the impact of martial activities. “[I]n the final reckoning,” noted Woodward, “American lives lost in the Civil War exceed the total of those lost in all the other wars the country has fought added together, world wars included. Questions raised about the proportion of space devoted to military events of this period might be considered in light of these facts.”5

The importance of military contingency lay at the heart of McPherson’s contribution to a debate, fiercely contested in the 1970s and 1980s, about whether the Confederacy collapsed due to internal or external factors.6 An influential stream of scholarship attributed defeat to class tensions, restive enslaved people, disaffected slaveholders who questioned the Confederate cause, and a general absence of true national sentiment. McPherson addressed this scholarship and its conclusions in his final chapter: “‘So the Confederacy succumbed to internal rather than external causes,’ according to numerous historians. The South suffered from a ‘weakness in morale,’ a ‘loss of the will to fight.’ The Confederacy did not lack ‘the means to continue the struggle,’ but ‘the will to do so.’”7

McPherson labeled such arguments less than convincing because “the North experienced similar internal divisions, and if the war had come out differently the Yankees’ lack of unity and will to win could be cited with equal plausibility to explain that outcome.” Among all explanations for Confederate failure, “the loss of will thesis suffers most from its own particular fallacy of reversibility—that of putting the cart before the horse. Defeat causes demoralization and loss of will; victory pumps up morale and the will to win.”8

This is not to say McPherson failed to examine how internal ruptures and friction plagued the Confederate war effort. He detailed economic hardships that undercut efforts to field and supply armies while also providing goods for people on the home front. “Under the pressures of blockade, invasion, and a flood of paper money,” he observed, “the South’s unbalanced agrarian economy simply could not produce both guns and butter without shortages and inflation.”9 “The specter of class conflict also haunted the South,” a phenomenon that, as in the United States, worsened with conscription. Anti-war and peace groups arose in the Confederacy, and a “rich man’s war/poor man’s fight theme stimulated the growth of these societies just as it strengthened copperheads in the North.” Such activity “drained vitality from the Confederate war effort in certain regions and formed the nucleus for a significant peace movement if the war should take a turn for the worse.” Overall, however, it was not “especially a poor man’s fight” in the Confederacy—“Probably no more than it was in the North.”10

McPherson gave military operations primacy in explaining fluctuations of morale—or the will to resist—in the Confederacy. Amid an array of economic stresses on the home front during the winter of 1862–1863, “Military success was a strong antidote for hunger. Buoyed by past victories in Virginia and the apparent frustration of Grant’s designs against Vicksburg, the South faced the spring military campaigns with confidence.”11 Over the long sweep of the conflict, Confederate military leadership could have won the war; in fact, in the eastern theater “the genius of Lee and his lieutenants nearly won it, despite all the South’s disadvantages.”12

Yet Union military triumphs at crucial periods proved fatal to the Confederacy. “Most attempts to explain southern defeat or northern victory,” insisted McPherson, “lack the dimension of contingency—the recognition that at numerous critical points during the war things might have gone altogether differently.”13 He offered four major turning points that profoundly shaped the direction of the war, the last three of which featured Union victories: In the summer of 1862, Confederate counteroffensives derailed what appeared to be decisive Union operations against Richmond and in the West; that autumn, United States forces turned back Confederate invasions of Kentucky and Maryland; between July and November 1863, victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga shifted the tide toward ultimate Union victory; and in the fall of 1864, operations against Atlanta and in the Shenandoah Valley reelected Abraham Lincoln and extinguished any serious possibility for Confederate independence. Absent William Tecumseh Sherman’s and Philip H. Sheridan’s victories in September and October, Lincoln faced possible defeat in 1864, “as he anticipated in August,” in which case “history might record Davis as the great war leader and Lincoln as an also-ran.”14

Although McPherson did not specifically engage with literature that debated whether Confederates developed a sense of true nationalism, he illuminated the issue in his treatment of controversy in late 1864 and 1865 about arming some enslaved men.15 Ardent Confederate nationalists such as Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee supported the idea, and Lee, who thought the proposal “not only expedient but necessary,” would exert “a decisive influence” in marshaling support.16 Confederates who had established a new republic to safeguard their slavery-based society thus loosened control over millions of enslaved people in pursuit of national independence. In the end, they lost both their republic and the institution of slavery.

Gary W. Gallagher is the John L. Nau III Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Virginia.

Responses and Reflections

By James M. McPherson

Joe Glatthaar’s succinct summary of the dueling traditions in Civil War historiography pays Battle Cry of Freedom a handsome compliment when he writes that it successfully married the two. That is precisely what I tried to do in the book. Joe correctly asserts that most academic scholars focused mainly on the political, social, economic, cultural, racial, or gender issues of the era and largely avoided the actual war, which resulted in the deaths of more Americans than in all the rest of the nation’s wars combined. This omission left a huge hole in our understanding of the war’s impact that I was determined to fill. As I wrote in the preface of Battle Cry, “Most of the things that we consider important in this era of American history—the fate of slavery, the structure of society in both North and South, the direction of the American economy, the destiny of competing nationalisms in North and South, the definition of freedom, the very survival of the United States—rested on the shoulders of those weary men in blue and gray who fought it out during four years of ferocity unmatched in the Western world between the Napoleonic Wars and World War I.”

Glatthaar has nicely fitted Battle Cry into the context of Civil War scholarship. There is also another context for the book—it is one of 10 volumes in the Oxford History of the United States. This series was the brainchild of three giants of 20th-century American history scholarship and publishing: C. Vann Woodward, Richard Hofstadter, and Sheldon Meyer, the history editor of the American branch of Oxford University Press. In the early 1960s they conceived the series as a counterpart to the famous Oxford History of England. Each volume was to treat a distinct period in American history: for example, the Revolution and formation of the Constitution (1763–1789); the Jacksonian Era (1815–1848); and so on. Two specialty volumes were to cover the entire chronology of the American experience: economic history and diplomatic history, but these were not to preclude treatment of the same topics in the chronological volumes. Each book was to be written by a leading historian in its field, to bring the best and most recent scholarship to a broad reading public as well as to fellow historians, to weave together political, social, economic, military, and cultural history, and to be written in an accessible narrative style intended to reach a large readership.

Edited in Prisma app with Curly Hair

This was a tall order, but Woodward, Hofstadter, and Meyer were confident they could pull it off. They set forth to recruit authors with the hope that some—perhaps even all—of the volumes could be published by the time of the bicentennial in 1976. This hope turned out to be wildly overoptimistic. The series was star-crossed from the outset. Hofstadter became ill and died prematurely in 1970. Several potential authors declined invitations to write volumes that seemed impossibly ambitious. Others accepted the assignment but subsequently backed out. Three historians actually produced manuscripts on Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, the Jacksonian period, and economic history that were rejected by Woodward and Meyer because they fell short of the criteria of coverage or accessibility. The first volume to be published, in 1982, was Robert Middlekauff’s The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789.

Meanwhile, Vann Woodward persuaded me in 1976 to sign a contract to write the Reconstruction/Gilded Age volume. The timing of this commitment was not ideal, for while I had taught a course on this period for several years, and had just finished a book on the 1870–1910 period (The Abolitionist Legacy), my first two books had been about the Civil War, I was now teaching a course on that subject, and was working on a Civil War textbook (Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction, published in 1981). The planned volume on the Civil War era in the Oxford History (1848–1865) had experienced its own tribulations. Woodward and Hofstadter had first offered that volume to Bruce Catton, but he declined because while he was confident he could handle the military and politics of the subject he had little desire to undertake the broader scope of the series parameters. The editors next went to Kenneth Stampp, who agreed but later backed out because he was reluctant to take on the military dimension and did not want to write Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark. Woodward next talked Willie Lee Rose into accepting the task. She would have done a great job, I think, but in 1978 she suffered a stroke that severely impaired her ability to speak and write. As it became clear that she would not recover that capacity and that my own recommitment to the Civil War was ascending while my commitment to the Gilded Age was fading, I persuaded Woodward and Meyer to let me switch to the 1848–1865 volume. And thus Battle Cry was born.

When I recently reread the book for the first time in many years, I found myself reflecting on some of the points made by the four historians who have commented on it above. I did not realize that, as Matthew Stanley notes, the word freedom appears 98 times in the text as well as once in the title. The book explores the profound irony that both sides—or as Stanley puts it, all sides—professed to be fighting for that precious heritage from the events of four score and seven years earlier. The Civil War shaped a new birth of freedom whose meanings and significance we are still trying to understand and implement today.

And as Jenny Weber notes, my purpose in the book was to embed analysis in the narrative. This effort not only fit the purpose of the Oxford History series but also represents my own approach to the writing of history. After all, history is a story of events that took place in the past and that help us understand how the present came to be. And as Gary Gallagher writes, I “crafted Battle Cry as a detailed narrative that underscored the power of historical contingency.” This theme of contingency lies at the heart of the book, indeed at the heart of history itself and at the heart of any story, fictional or nonfictional. What is historical contingency? It is a recognition that human events are not foreordained or inevitable; that they are unpredictable consequences of human agency, human decisions. Confederate militia at Charleston were not foreordained to fire on the American flag at Fort Sumter; that event was contingent on Abraham Lincoln’s decision to resupply the fort and Jefferson Davis’ decision to prevent that resupply and to capture the fort. Richmond was not certain to remain under Confederate control in June 1862; that outcome of George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign was the result of the general’s timidity and Lee’s aggressive counteroffensive. Lincoln’s reelection in 1864 was not inevitable; it was dependent on William T. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta and Philip Sheridan’s decisive victories in the Shenandoah Valley. The abolition of slavery was not certain before 1865; it was contingent on Union victory, which appeared unlikely during much of the previous four years. I think that part of the success of Battle Cry came about because it was written in a manner that took into account the uncertain contingencies of these and many other events and developments in the war. One of my favorite moments during the numerous interviews and lectures I did to publicize the book was the remark by a South Carolinian that Battle Cry was his favorite Civil War book because while reading it he fantasized that the war might come out differently.

Notes

1. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York, 1988), 640.

2. “Disney Vows to Seek Another Park Site,” The New York Times, September 30, 1994

3. McPherson finished the book just before scholars produced rich bodies of work on, among other topics, common soldiers and women and gender. See, for example, George C. Rable’s Civil Wars: Women and the Crisis of Southern Nationalism (1989), Drew Gilpin Faust’s Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War (1996), and Reid Mitchell’s Civil War Soldiers: Their Expectations and Experiences (1988).

4. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 283–284.

5. Ibid., xix.

6. For two key titles that highlighted internal causes, both of which McPherson cited, see Richard E. Beringer, Herman Hattaway, Archer Jones, and William N. Still Jr., Why the South Lost the Civil War (1986), and Kenneth M. Stampp, The Imperiled Union: Essays on the Background of the Civil War (1980), especially chapter 8.

7. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 855.

8. Ibid., 856, 858.

9. Ibid., 442.

10. Ibid., 611, 613–614.

11. Ibid., 625.

12. Ibid., 857.

13. Ibid., 857–858.

14. Ibid., 857.

15. On Confederate nationalism, see Emory M. Thomas, The Confederate Nation, 1861–1865 (1977); Beringer et al., Why the South Lost; and Drew Gilpin Faust, The Creation of Confederate Nationalism: Ideology and Identity in the Civil War South (1988). For the trajectory of internal cause arguments, see Gary W. Gallagher, “Disaffection, Persistence, and Nation: Some Directions in Recent Scholarship on the Confederacy, in Civil War History 55 (September 2009): 329–353.

16. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 836.