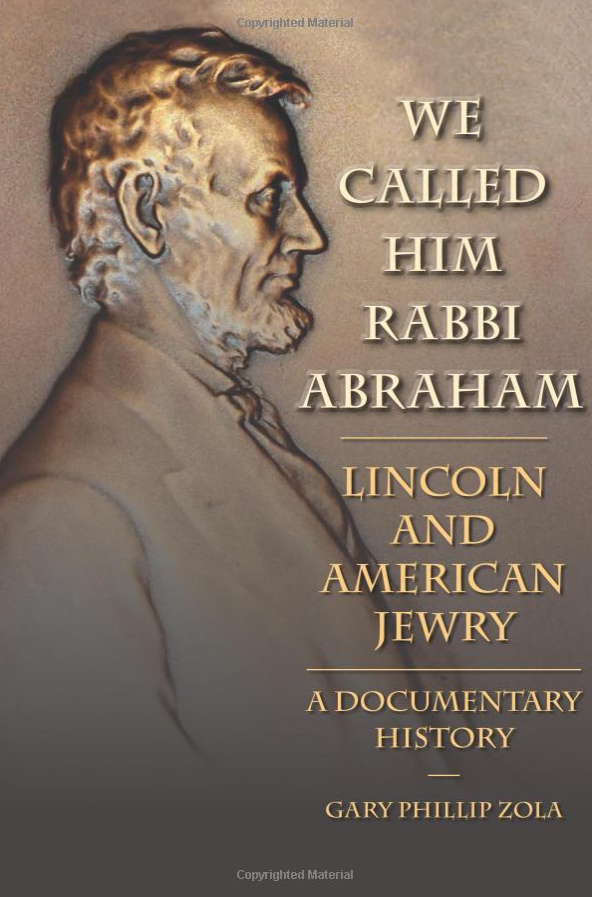

We Called Him Rabbi Abraham: Lincoln and American Jewry, A Documentary History by Gary Phillip Zola. Southern Illinois University Press, 2014. Cloth, IBSN: 978-0809332922. $49.50

A number of years ago, I presented a paper on the Jews of New York City during the Civil War in which I described the hostility of the majority of the Jewish community to the Republican party in general and Lincoln in particular. I noticed a sudden reversal took place after Lincoln’s assassination. Not only was there universal mourning of the martyred president, but it triggered a transformation that reached deeply into the city’s soul including its sizable Jewish population. It is not surprising that the most prominent New Yorker after the War was no longer Democrat August Belmont, but rather banker Joseph Seligman, long a supporter of Lincoln.

A number of years ago, I presented a paper on the Jews of New York City during the Civil War in which I described the hostility of the majority of the Jewish community to the Republican party in general and Lincoln in particular. I noticed a sudden reversal took place after Lincoln’s assassination. Not only was there universal mourning of the martyred president, but it triggered a transformation that reached deeply into the city’s soul including its sizable Jewish population. It is not surprising that the most prominent New Yorker after the War was no longer Democrat August Belmont, but rather banker Joseph Seligman, long a supporter of Lincoln.

Gary Zola’s fine book justifies my tentative hypothesis. He presents both a narrative and a documentary history of Jews’ relationships with Lincoln, both when the president was alive and after his assassination. Not surprisingly, two thirds of the book discusses the period after Lincoln’s death, for Jewish encounters with Lincoln were relatively few in his years as an Illinois lawyer and politician and as President. But Zola demonstrates that they were uniformly benevolent. In the most notable confrontation—the infamous Orders No. 11 in December 1862 that ordered all Jews out of Grant’s military Department of Mississippi because the Jews “as a class” violated “every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department”—Lincoln treated the Jewish delegations with great kindness and, more importantly, acted immediately to rectify the situation. The exchange between Lincoln and Cesar Kaskel, an emissary to Lincoln, is exemplary:

Lincoln: So the Children of Abraham were driven from the happy land of Canaan?

Kaskel: Yes and that is why we have come unto Father Abraham’s bosom, asking protection.

Lincoln: And this protection they shall have at once. (98)

In a second mater of great concern, Lincoln quickly moved to have Congress permit Jewish chaplains, and that was quickly accomplished.

Zola demonstrates the ambivalent and even hostile feelings toward Lincoln felt by many Jewish leaders such as Isaac Mayer Wise, leader of the Reform movement, and Morris Raphall, the most prominent rabbi in New York City. Wise considered Lincoln’s election “one of the greatest blunders a nation can commit.” He thought Lincoln an amateur, criticizing his extravagance and his “careless” writing. He noted that Lincoln received “the heaviest vote of infidels ever given to any man in this country” (205). As late as August 1864, he criticized the Republicans equally with slaveholders as factions that “hurled this nation into this abyss of destruction” (208). Raphall, who had in 1861 given a notorious speech arguing that the Bible justified slavery, remained critical of Lincoln throughout the war, blaming the conflict on “demagogues, fanatics and a partisan press” (215).

Wise changed his mind decidedly after the war, as did almost all Jewish leaders. During the next half-century, Lincoln became a hero of Jewish society, incorporated by some as a member of the community. Indeed, Wise, who quickly became one of Lincoln’s prominent eulogists, declared: “Remember, simply, that our President, the chosen banner-bearer of our People. The Messiah of this country, was slain by the assassin’s hand in the midst of is people and we must cry with Cain, “Mine iniquity is greater than I can bear” (163). Wise also asserted that Lincoln told him that he “believed himself to be bone from our bone and flesh from our flesh. He supposed himself to be a descendant of Hebrew parentage. And, indeed, he preserved numerous features of the Hebrew race, both in countenance and culture.”

Whether or not most Jews believed that Lincoln was actually a Jew, the writings of many prominent Jewish leaders in the next half century clearly showed that they cherished that Lincoln had adopted the tenets of the Jewish religion in many of his writings and orations. In 1909, Rabbi Leonard Levy of Pittsburgh remarked that, “Lincoln, though religious, was not a believing and confessing Christian.” Levy vowed that he “shall trust myself to the God Lincoln loved, with much more confidence that the god of recreant kings and persecuting ecclesiastics” (259). Like Moses, Lincoln was a liberator, and the “cause of the downtrodden and the oppressed” was his cause. Jewish educator Edward A. Fischkin praised Lincoln as an upholder of Jewish ideals, notably the Ten Commandments, as “antislavery is the livening idea, the moving spirit, the essence of the Thora” (261). Lincoln’s words and actions reverberated with the Jewish soul. Solomon Schechter, the great scholar and founder of the American conservative movement, was from an early age a student and admirer of Lincoln. He was deeply moved by the Second Inaugural in its understanding of the inscrutable ways of God. He saw great profundity in Lincoln’s words: “To take upon one’s self the burden of humiliation in which a whole nation should share, is another feature of religious mysticism which realizes in the sphere of morality the unity of humanity and in the realm of history the union of the nation, so that it does not hesitate to suffer and to atone for the sins of the generation” (263).

Zola’s book is encompassing. He discusses Jewish sculptors of Lincoln, the design of the Lincoln penny, and the biographies of Samuel Markens and Emmanuel Herz, both of whom spent their lifetimes gathering information on Lincoln and the Jews. In a chapter entitled “Lincoln! Though sholdst be Living at this Hour!,” he reveals how Lincoln was invoked by Jewish leaders in times of industrial conflict, at the coming of World War II, and during the years of McCarthyism and the struggle for Civil Rights. In sum, this timely, well researched, and immensely thorough book will give readers valuable insight and understanding into the role that Lincoln played within the various Jewish communities both before and during his presidency. Most importantly, it shows just how deeply Lincoln became embedded into the saga of American Jewry, despite the fact that most Jews and their families immigrated long after his death.

Howard B. Rock is Professor of History, Emeritus at Florida International University and the author of Haven of Liberty: New York Jews in the New World, 1654-1865 (2013).