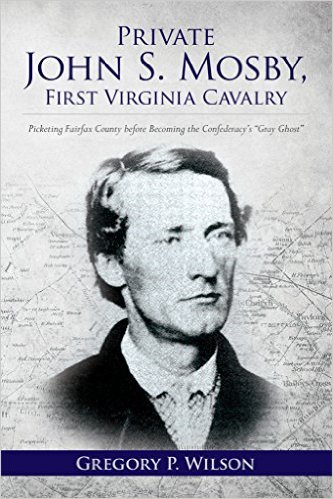

Private John S. Mosby, First Virginia Cavalry: Picketing Fairfax County Before Becoming the Confederacy’s “Gray Ghost” by Gregory Wilson. CreateSpace, 2015. Paper, ISBN: 978-1517255855. $25.00.

Before he rode to glory at the head of his Rangers, John S. Mosby was a lowly private in the First Virginia Cavalry, serving in northern Virginia. It was here that this unassuming Virginia lawyer learned the craft of war and went on to become the “Gray Ghost of the Confederacy.” Mosby’s early career is chronicled in a new book by Gregory Wilson, who is a consultant in the financial industry.

Before he rode to glory at the head of his Rangers, John S. Mosby was a lowly private in the First Virginia Cavalry, serving in northern Virginia. It was here that this unassuming Virginia lawyer learned the craft of war and went on to become the “Gray Ghost of the Confederacy.” Mosby’s early career is chronicled in a new book by Gregory Wilson, who is a consultant in the financial industry.

The author’s aim is to provide background on Mosby and how he later developed into the guerilla chieftain. The book opens with a brief biography of his early years in Virginia, his attendance at the University of Virginia, and Mosby’s years as a lawyer in the Virginia piedmont. On a lark, he was asked by a close friend, William W. Blackford (later a key member of J.E.B. Stuart’s staff), to join the local cavalry militia company, the Washington Mounted Rifles. The author writes that Mosby was an “indifferent soldier” who missed drills.

Mosby was initially pro-Union, but he cast his lot with Virginia when his state seceded. Wilson downplays Mosby’s ownership of two young female slaves, but notes that he brought one of his father’s slaves, Aaron Burton, with him to war to act as his camp servant. Wilson observes that Burton and Mosby formed a close friendship together. Shortly before he died, Mosby penned in a private letter that “slavery was, in fact, the primary impetus for the South’s rebellion and the cause of the war.”

Mosby missed the fighting at First Manassas and spent the remaining months of 1861 on picket duty in northern Virginia. The author includes some of Mosby’s wartime letters within the text and then presents some views from Mosby’s postwar memoirs. In several instances, t is interesting to see how his views changed and/or were distorted from the contemporary letters to the memoirs, published long after the war. The author chronicles Mosby’s participation in several forgotten skirmishes in northern Virginia through the end of 1861 and 1862. He participated as a scout on Stuart’s staff, gaining experience that he would later use as commander of the Rangers. The book concludes with Mosby’s transfer to the Virginia Peninsula and eventual return to northern Virginia as commander of the 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, better known as “Mosby’s Rangers.”

This book does present an interesting view of the development of John Mosby from a rural Virginia lawyer into the feared guerilla leader of “Mosby’s Confederacy.” It is clear that his experience as a member of the First Virginia Cavalry prepared him for his role later in the war. While the book is well written, it does suffer from a few of the drawbacks common to the current print on demand publishing system. The maps are of decent quality, but many of the images in the book did not reproduce clearly and are distracting. In addition, while Wilson used a good number of printed primary sources and some period newspaper accounts, a little digging through some archives might have turned up some Mosby sources not previously known. Despite this, for those wanting an understanding of the development of John Mosby, this is a good read.

Robert Grandchamp earned his M.A. in American History from Rhode Island College. The author of nine books on American military history, he is an analyst with the federal government and resides in Jericho Center, Vermont.