Author's collection

Author's collectionRich Condon addresses the audience at a public history event held in Pittsburgh in 2019.

What is public history? What makes it “public?” How is it different from the history concentration in a school catalog? What sets public historians apart from academics? These are all questions I have encountered over my decade in the history field. Whether I was working as an interpreter for the Battle of Franklin Trust, volunteering to lead educational programs through the halls of Pittsburgh’s Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall and Museum, or in my six years as a ranger with the National Park Service, these questions always sparked constructive conversation about an area of the history discipline that has existed for generations, yet only recently been understood as an important part of historical interpretation. If you have ever traveled to favorite museums, battlefields, national parks, and historic sites and enjoyed an educational, or “interpretive,” program with a park ranger, a volunteer, a docent, a living history actor, or a museum professional, or interacted with a site’s exhibit space, you, too, have engaged public history.

The field has in recent years become more familiar to those who study history, but they may still have a difficult time assigning an all-encompassing definition to this area of historical study. Public history can be seen as a bridge between academic studies and the general public’s broader understanding of history. Public historians are communicators, storytellers, and supporters of broader historical enlightenment through tangible and intangible interactions. Our successes can be measured in our fueling of public interest in our shared history, or feeding the imaginations of future historians who will be the next generation to walk the halls of our museums, schools, historic sites, and battlefield parks. In many cases, we answer the unexpected questions, the larger and more complex questions related to our subject, our site, or our stories—the most common and overarching one being: Why does what happened here matter? History’s relevance to a society, its impact on contemporary communities, and how it shapes our modern world are all routes to a dialogue that produces a deeper connection between questioner and the historical past.

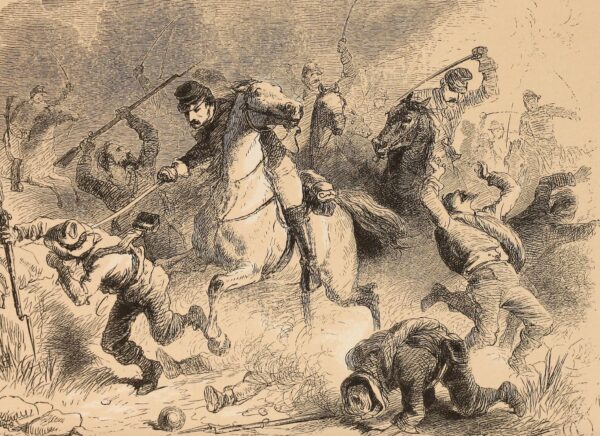

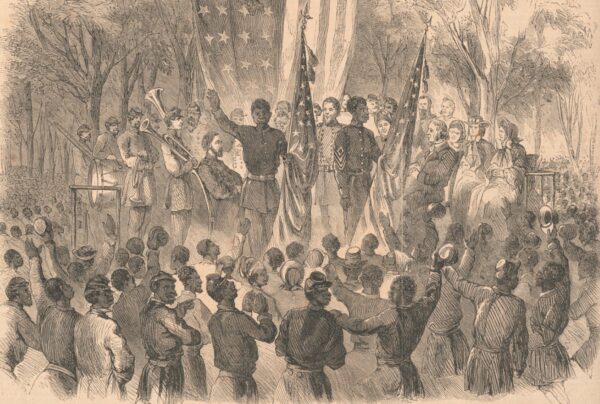

This is not to say that public history doesn’t have its share of challenges. The history that is interpreted at sites can vary from stories of local interest to broad conversations of national import. Public historians are often charged with addressing difficult conversations ranging from the enslavement of African people in America to the long and bloody Civil War that ended that peculiar institution, from the Reconstruction period to the Civil Rights era that attempted to deliver on promises made a century earlier. It is the job of public historians to make events and their repercussions as approachable as possible while doing justice to the stories of real people being interpreted on a day-to-day basis. Their task is to convey a shared history while also preparing for not-always-predictable reactions from their audience. A common challenge is disagreement about how a story is interpreted. Just as, for example, the effects of a novel, a made-up story, on a reader may differ, the same may apply to the effects of documented history, a true story, on a citizen. What historical event one visitor considers traumatic and painful may be viewed by another with indifference or callousness. For many years, Confederate iconography has sparked controversy across the nation, leading to conversations about the impact of historical myth and memory and, from there, discussions about the causes of the Civil War and the goals of Reconstruction.

Author's collection

Author's collectionThe author talks to visitors during a public program held at Beaufort National Cemetery in the summer of 2023.

Though the past is set, history is our ever-refining comprehension and interpretation of the past built on evidence including artifacts, journals, letters, oral histories, photography, film, and other primary sources in whatever form they exist. It is up to us public historians to use these tools to tell a fuller story to the best of our ability. Modern forms of communication, such as digitized archives and historical photography, television and movies, podcasts, social media, magazines and books, all help to usher history into the homes of those who may not otherwise have access to such resources. Many people have probably at least once absorbed history through a popular podcast or radio show, a new historically influenced movie, or an article trending online. In many cases, people may not even realize they are engaging with a form of public history. If you have explored historical roots in your community with a friend, or discussed family history with a relative, you have actively engaged with a shared history, or the discipline of public history, in some capacity. With that being said, good public historians base their programming around current scholarship along with well-sourced research, and often are on the frontline of interpretation, interacting with those who seek to know more.

As defined by the National Council on Public History, public historians “come in all shapes and sizes” as “historical consultants, museum professionals, government historians, archivists, oral historians, cultural resource managers, curators, film and media producers, historical interpreters, historic preservationists, policy advisers, local historians, and community activists,” in addition to playing many other roles. In most cases public historians’ work is done alongside those who provide services complementary to the historians’ field. Examples can be found at any National Park Service managed battlefield park. A public historian, also referred to as an interpreter, connects visitors to the park’s resources—whether it be artifacts, historic structures, natural landmarks, or the battlefield itself—through research and interactive programming. Those resources need protection and management through maintenance, law enforcement, and administrative coordination. While the associated parties involved might not have the background, or training, that a public historian does, their valuable skills and cohesive efforts contribute toward a common goal: preserving the natural and cultural resources of their site for the “enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” This is all done through professional collaboration, community partnerships, and stakeholder relationships—all of which have a connection with the public historian.

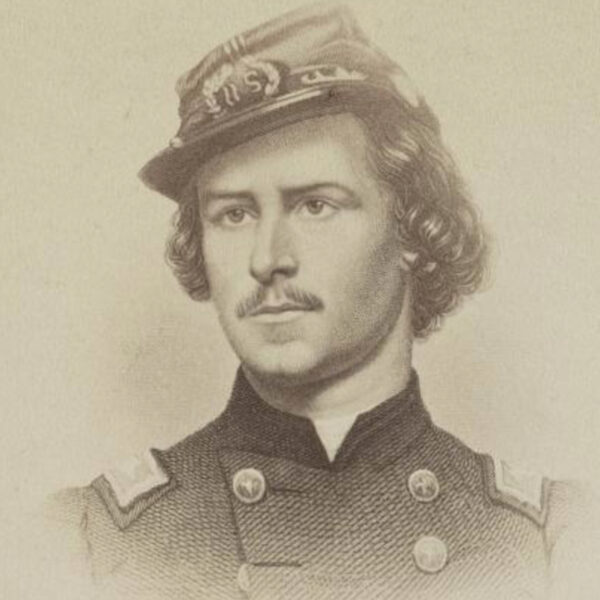

Public historian, author, and my fellow Pittsburgh native David McCullough reflected on his career path in a 2003 speech delivered to the Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities. He recalled the moment that began his love affair with history, the graduation present he was given of Bruce Catton’s A Stillness at Appomattox that ignited his interest in the Civil War. He said he thought “maybe someday I might try writing something of the kind.” Those who have followed McCullough’s work through titles such as The Johnstown Flood, 1776, and John Adams, or have heard his somber voice narrating Ken Burns’ 1989 documentary, The Civil War, can understand the role popular history and historians play in engaging the public with our nation’s past. It was not lost on McCullough, who, like so many other public historians, believed that “there should be no hesitation about teaching future teachers with books they will enjoy. No harm’s done to history by making it something someone would want to read.”

Rich Condon is a historian from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who earned his BA in Public History from Shepherd University. For over a decade he has worked with a multitude of sites and organizations including The Battle of Franklin Trust, the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall and Museum, Flight 93 National Memorial, Reconstruction Era National Historical Park, and Catoctin Mountain Park. He has written for Civil War Times, The American Battlefield Trust, as well as Emerging Civil War, and currently operates the Civil War Pittsburgh blog, which focuses on sharing stories related to western Pennsylvania’s role in the Civil War.