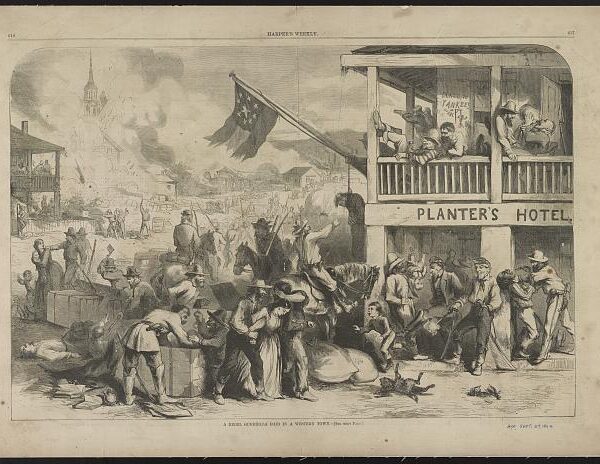

A Selection of War Lyrics (1864)

A Selection of War Lyrics (1864)Union cavalrymen chase down Confederate soldiers in a wartime illustration by F.O.C. Darley

In the Voices section of our Summer 2024 issue we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers that revealed their thoughts about killing the enemy. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“[T]he sight of the wounded and dead men was very solemn. It was necessary, however, and I take my full share of responsibility….”

—Captain William P. Lyon, 8th Wisconsin Infantry, in a letter home after the Battle of Fredericktown, Missouri, October 25, 1861

“My nearest comrade … drew up his faithful Springfield and taking deliberate aim—I fear with malice aforethought and intent to kill—fired. My friend is a good marksman, and as secesh was not seen afterwards, the presumption is that he had an extra hole made through his body…. Such are the horrors of war.”

—Wilber Fisk, 2nd Vermont Infantry, on an incident he witnessed while on picket, in a letter to his hometown newspaper, April 24, 1862

“[I]t was a remarkable shot; but I am thankful to say that every man who witnessed the act pronounced it contemptible and cowardly.”

—Union surgeon John G. Perry on witnessing a sharpshooter killing of a Confederate officer during the Siege of Petersburg, in a letter home, June 20th, 1864. The Union general who had ordered the sharpshooter to “pick off that man,” Gardner wrote, “later acknowledged and deeply regretted his fatal impulse.”

“[W]e have got used to hearing the big guns that we don’t care any thing about it when we go up to Shoot at the rebels we go as we use to for Co drill all the boys feeling as light harted as if they were at home going into the field to work….”

—Dolphus Damuth, 29th Wisconsin Infantry, on him and his fellow sharpshooters heading to their daily duty during the Siege of Vicksburg, in a letter to his sister, June 9, 1863

“I don’t know that I ever shot any one or dont want to know.”

—Numa Barned, 73rd Pennsylvania Infantry, in a letter home in 1862. Barned, a combat veteran, added, “I do not want any man’s blood on my hands.”

“[I]t wer my duty to Shoot as many of the Devils as I could and so i did.”

—Michael Donlon, 20th Massachusetts Infantry, in a letter to his brother about his participation in a recent battle, May 21, 1864

“I emptied my cartridge box many times during the day as did the others. I saw men often drop after shooting, but didn’t know that it was my bullet that did the work and really hope it was not.

But you know that I am a good shot.”

—Chauncey Cooke, in a letter to his parents, May 18, 1864

“[W]hen we were not fighting we ate, lounged, smoked, and slept. Some of the officers tried sharpshooting, but I could never bring myself to what seemed like taking human life in pure gayety, and I had not as yet learned to play euchre.”

—Captain John William DeForest, 12th Connecticut Infantry, in his journal during the Siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana

“[O]h that I never could behold such a sight again to think of it among civilized people killing one another like beasts one would think that the supreme ruler would put a stop to it but wee sinned as a nation and must suffer in the fleash as well as spiritually those things wee cant account for.”

—S.G. Pryor, 12th Georgia Infantry, recounting his recent experience in battle in a letter to his wife, May 18, 1862

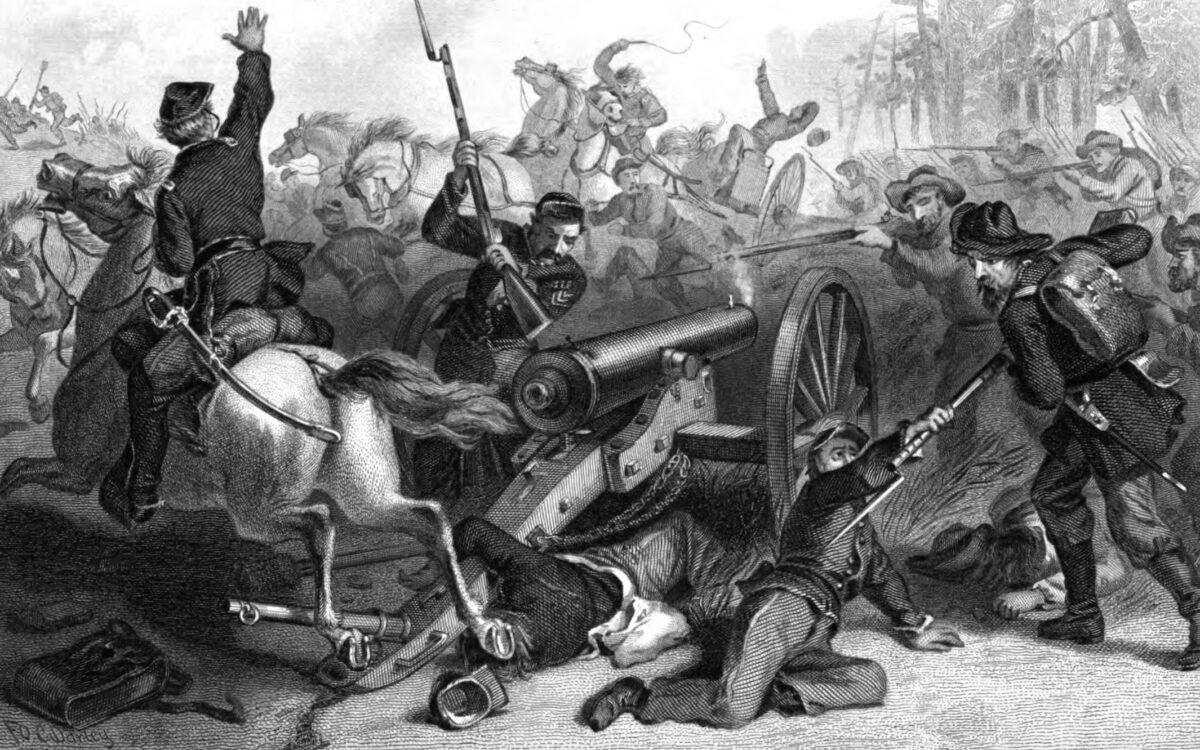

Gen Robert E. Lee (1897)

Gen Robert E. Lee (1897)Union and Confederate soldiers fight hand-to-hand in a depiction of the Battle of Antietam.

“I had the pleasure of shooting three rebels dead and wounding another.”

—Union soldier W.O. Lyford, in a letter to his father after the Battle of Manassas, July 22, 1861

“The chaplain gives me the credit of killing a colonel or field-officer commanding a regiment; and I know that I did my best. I drew as level a bead on his belt, as he waved his sword and cheered his men forward, as ever I drew on a squirrel—and I know I can cut a pigeon’s head off with the same gun, at the same distance he was; and I know, too, that when my smoke blew away, his saddle was empty! Sometimes I wonder if it is right for a man to single out his mark that way; but I couldn’t help it. The colonel was doing more against us than any man I could see, and I felt that it would help us most to drop him. Was I justified?”

—William M. McLain, 32nd Ohio Infantry, in a letter about the Battle for Atlanta, August 8, 1864

“Where I used to hunt squirrels and birds I now hunt men and the game is plentiful.”

—Captain Samuel D. Buck, 13th Virginia, in his memoir of the war

“We have no arms now but I expect them soon and then hope to have one chance before the War ends as I do want to shoot a Yankee….”

—Winston Stephens, 2nd Florida Cavalry, in a letter to his wife, July 6, 1862

“I intend to kill at least one secesh. God being my helper.”

—Captain Luther H. Cowan, 45th Illinois Infantry, in a letter to his wife, February 1–2, 1862

“I feel that I would like to shoot a Yankee, and yet I know that this would not be in harmony with the Spirit of Christianity, that teaches us to love our enemies & do good to them that despitefully use us and entreat us.”

—Mississippi cavalryman William L. Nugent, in a letter to his wife, August 1861

“I came to aim, steadied my piece, and aiming at his breast, I fired—I saw him no more, God have mercy on him—the distance was about 70 yds and I could not miss him.”

—Frank Potts, 1st Virginia Infantry, on his experience at the Battle of Blackburn’s Ford in July 1861, in his diary

“One officer, not more than thirty feet from where I stood, quietly loaded up an old meerschaum, lit a match, his pistol hanging from his wrist, and when he had got his pipe well agoing, he got hold of his pistol again and went on popping away at us as leisurely as if he had been shooting rats. Why that fellow didn’t get shot I don’t know. The fact is when you start to draw a bead on any chap in such a fight you have to make up your mind mighty quick whom you’ll shoot. There are so many on the other side that look as if they were just getting a bead on you that it takes a lot of nerve to stick to the one you first wanted to attend to. You generally feel like trying to kind of distribute your bullet so as to take in all who ought to be hit. So a good many get off who are near enough to be knocked over the first time.”

—First Lieutenant Henry O. Dwight, 20th Ohio Infantry, in a postwar account of the May 1863 Battle of Raymond, Mississippi

“In front of us was a reb in a red shirt, when one of our boys, raising his gun, remarked, “see me bring that red shirt down,” while another cried out, “hold on, that is my man.” Both fired, and the red shirt fell—it may be riddled by more than those two shots. A red shirt is, of course, rather too conspicuous on a battle field.”

—Osborn H. Oldroyd, 20th Ohio Infantry, on an incident during the Battle of Raymond, in his diary, May 12, 1863

“Poor fellows, I can’t help pitying them if they are Rebels, for they have no doubt been deceived. In the excitement of battle I could aim at them when only forty or fifty yards from me, as cooly as I ever did at a squirrel. But now it seems very much like murder. They would throw up their hands and fall almost every time we would get a fair shot at them, and we would laugh at their motions and make jest of their misfortune. I don’t nor can’t imagine now how we could do it. The fact is, in battle, man becomes a sinner and delights in the work of death. And if his best friend falls at his side he heeds it not, but presses on eager to engage in the wholesale murder.”

—Sergeant John G. Marsh, 29th Ohio Infantry, in a letter to his father about the Battle of Winchester, April 12, 1862

“I used to think it was all for the country, and wanted a chance to kill something, but I find it is mostly a money making, avaricious, nigger-worshipping matter; only benefitting the ambition of a few, and causing needless suffering and misery all over the North, and now I would not of my own free will, fire a shot, or march forty rods for all the schemers, or abolitionists from Washington City to the ‘Daily Life’ office.”

—Richard Robert Crowe, 32nd Wisconsin Infantry, in a letter to his mother, July 18, 1864

“We pulled down on each other about the same time, but he fired first and his ball struck me on the hip, making me flinch and throwing me off my aim. This made me a little mad, and I reloaded in a hurry. Just as he raised his gun to fire I pulled trigger and his ball struck the ground close to my foot. ‘Did you hit him?’ Well, I am glad to say I don’t know, but I had a good aim at short range and the Springfield rifle that I used has brought squirrels out of the highest trees for me and never missed a hog, running or standing, under two hundred yards, especially when I was hungry, which my messmates can testify, was pretty much all the time.”

—Confederate cavalryman John Will Dyer, on his experience at the Battle of Resaca, in his memoir of the war

“You can kill me if you want to, but I am not going to appear before my God with the blood of my fellow man on my soul.”

—Texas Brigade soldier Val Giles, quoting a comrade’s response to their captain after the officer had threatened to “cut him down with his sword” if he didn’t stop shooting his gun “straight in the air” as the enemy advanced on them during the Battle of Chickamauga, in his memoirs

“I pigeon-holed my sentiments and shot for keeps.”

—David E. Holt, 16th Mississippi Infantry, on how he overcame his reluctance to fire at the enemy, in his memoir of the war. “I never enjoyed the sport of shooting at men,” he wrote. “There was no spirit of murder in my heart.”

My Story of the War (1888)

My Story of the War (1888)A depiction of Civil War combat by artist F.O.C. Darley

“I was behind a stump with three others we lay some time before we fired I as best I could to see where their fire came from presumably an object appeared that induced me to shoot but the load was wasted for I then discovered where they were. I loaded and looked and saw a curl of smoke leveled my gun and as he raised to fire I fired and there was no smoke come from that place if my ball killed any I have no regrets for I never took more deliberate aim at a wood pecker I fired some six times and the flag of truce was raised by them and then such a rush you never saw I had the curiosity to go in where I saw the smoke curl and found a Reb shot in the forehead he had a bad wound but did not look as though it hurt him much he had dropped a very nice Enfield Rifle which I captured and have yet I do not know whether they will let me keep it or not I will if possible.”

—John S.B. Matson, 120th Ohio Infantry, on the Battle of Arkansas Post, in a letter to a friend, January 20, 1863

“There are men bringing us ammunition and the men don’t put it in their cartridge boxes but lay it upon the logs in front of them to be convenient. Here they come again for about the sixth time, and they come like they are going to walk right over us. Now we give them fits. See how they do fall, like leaves in the fall of the year. Still they advance, and still we shoot them down—and still they come. Oh this is fun to lie there and shoot them down and we not get hurt.”

—Texas officer Samuel T. Foster, on the fighting at the Battle of Missionary Ridge, in his reminiscences of the war

“As I witnessed one line swept away by one fearful blast from … behind the stone wall, I forgot they were enemies and only remembered that they were men, and it is hard to see in cold blood brave men die.”

—Alexander Hunter, 17th Virginia Infantry, on watching the failed Union assault on Marye’s Heights during the Battle of Fredericksburg, in his memoir of the war

“No Christian nation can be justified in waging war in such a way as shall destroy five hundred and one lives, when the object of the war can be attained at a cost of five hundred. Every man killed beyond the number absolutely required is murder.”

—Winfield Scott, general-in-chief of the Union armies, in a comment made before the July 1861 Battle of Bull Run

“The man who shot him fell dead by my rifle. I felt bad at first when I saw what I had done, but it soon passed off, and as I had done my duty and was not the aggressor, I was soon able to fire again and again.”

—Massachusetts soldier Edwin Spofford, on engaging a member of a pro-secessionist mob who had just shot his comrade during the April 1861 Pratt Street Riot in Baltimore

“I snatched a gun from the hands of a man who was shot through the head, as he staggered and fell. At other times I would have been horror-struck and could not have moved, but then I jumped over dead men with as little feeling as I would over a log. The feeling that was uppermost in my mind was a desire to kill as many rebels as I could. The loss of comrades maddened me….”

—Oliver Willcox Norton, 83rd Pennsylvania Infantry, in a letter to his siblings about the Battle of Glendale, July 26, 1862

“I am only satisfied nowadays when I am fighting the enemy. The proper time to fight him is while he is on our northern soil. I shall kill every one of them that I can.”

—Union soldier William Henry Redman, in a letter to his mother during the Army of Potomac’s pursuit of retreating Confederates after the Battle of Gettysburg

“It is strange what a predilection we have for injuring our brother man, but we learn the art of killing far easier that we do a hard problem in arithmetic.”

—Henry Matrau, 6th Wisconsin Infantry, reflecting on the monthslong bayonet training he and his comrades received, in a letter to his parents, February 27, 1862

“When the shot was showering at us thick as hail, we loaded and fired at them as though we were shooting squirrels. I killed some very large Yankees, and feel as though I had discharged my duty….”

—A soldier from the 8th Georgia Infantry, on the Battle of Manassas in a letter to his hometown newspaper, July 24, 1861