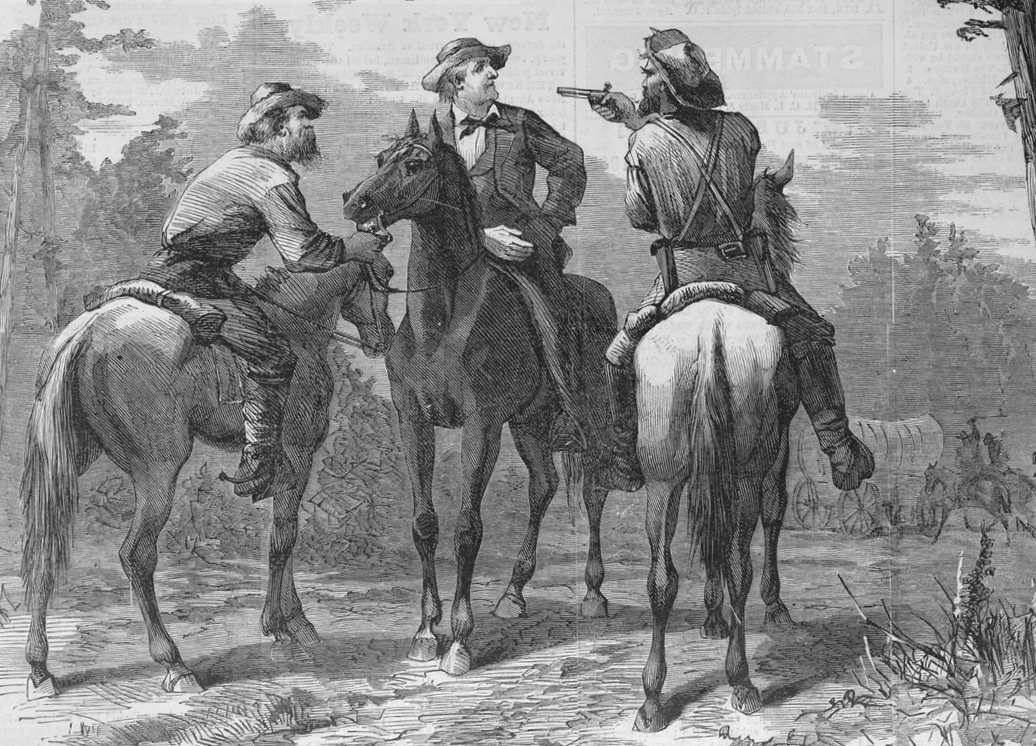

Two guerrillas stop a civilian rider to rob him in this sketch from a December 1864 issue of Harper’s Weekly.

“This Mr. Wales is a cold-blooded killer. He’s from Missouri where they’re all known to be killers of innocent men, women, and children.” That line from Clint Eastwood’s iconic 1976 film, The Outlaw Josey Wales, reflected—and in some cases still reflects—the three most enduring misconceptions about Civil War guerrillas. First was that irregular combatants were all bloodthirsty psychos. Second, that virtually all irregular combat was confined to the rough-and-tumble Missouri-Kansas borderlands. And third, that the activities of borderland bushwhackers, Jayhawkers, Red Legs, and raiders were distant from the “real war” and had nothing to do with its outcome.

Typically, historians complain about having to undo the damage caused by movies, television, and popular novels. In this case, Hollywood had taken its cues from scholarly literature. In the century after the Civil War, coverage of guerrillas actively fostered fallacies. From John Newman Edwards’ Noted Guerrillas (1877) to William E. Connelley’s Quantrill and the Border Wars (1909) to Albert Castel’s William Clarke Quantrill (1962), the irregular canon frequently revolved around a small cast of notorious men, depicted them as supernaturally violent, and dismissed their legitimacy as combatants. To be sure, the focus on villainous mustachios, quick-drawing gunmen, and homefront atrocities sold books—but it also helped maintain a clear, convenient, and ultimately artificial boundary between regular (read: “civilized”) and irregular (“uncivilized”) versions of America’s re-founding.

In reality, there is no monolithic guerrilla narrative because there was no single guerrilla war. Irregular conflicts followed regular soldiers everywhere: to the Indian territories of the Far West, the Trans-Mississippi Borderlands, the Midwest, Appalachia, and beyond. In some of these places, guerrilla violence predated formal militaries and Napoleonic maneuvers; in others, bushwhacking continued well after Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, and Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered their armies. Understandably, such a geographic expanse and the diversity of irregular combatants within it has made answering seemingly basic questions a difficult task. How many men fought as guerrillas? How many were killed? What did they do after the war? We simply don’t know—and probably never will with the specificity of the figures from the regular theater. The nature of guerrilla war does not lend itself to recordkeeping.

Since the 1980s, historians in the vanguard of Civil War guerrilla studies have tried to answer the more existential questions, often through localized lenses. What motivated men to fight as guerrillas? How did guerrilla warfare work logistically? What did it mean to be a “civilian” in a guerrilla-torn community? How did local governments and military officials deal with outbursts of guerrilla war? What did irregular violence mean to the outcome of the Civil War? Rather than rehashing which guerrillas were the bloodiest or which massacre the deadliest, the books listed here grapple with those bigger questions in unique ways. Each is a pioneer thematically, methodologically, or geographically so that each represents a significant turning point in how historians have explored the experiences of Civil War guerrillas.

Victims: A True Story of the Civil War (University of Tennessee Press, 1981) by Phillip Shaw  Paludan

Paludan

Philip Shaw Paludan’s Victims: A True Story of the Civil War has a tendency to slip under the radar in discussions of Civil War guerrilla literature. This unfortunate oversight is due partly to Paludan being best known as a historian of Abraham Lincoln and partly to the book’s chronicling of events far from Missouri and Kansas at a time when the western borderlands were still synonymous with homefront violence. In addition to being a beautifully written and accessible work of history, Paludan’s retelling of the 1863 Shelton-Laurel Massacre in North Carolina—in which 13 southern Unionists were summarily executed by regular Confederate forces—examines terrible acts of violence without playing to their sensationalism. Victims opened the door for micro- or community-level histories of irregular warfare in other parts of the country. Better still, the book set a new standard for illustrating how regular forces were often called on to deal with guerrillas and underscored how the definitions of “civilian” and “combatant” and the line that supposedly separated them were much more fluid than military historians traditionally depict.

Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri (Oxford University Press, 1989) by Michael Fellman

Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri (Oxford University Press, 1989) by Michael Fellman

With Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the American Civil War, Michael Fellman set out to dissect what he correctly labeled the “war of 10,000 nasty incidents.” At first glance, a return to the well-trod Missouri-Kansas borderlands might seem like a retrogression, especially after Victims; but in fact, it was high time for a professional historian to finally confront more than a century’s worth of myth and hyperbole surrounding the likes of William Clarke Quantrill, William “Bloody Bill” Anderson, Jayhawker chieftains Jim Lane and Charles “Doc” Jennison, and the infamous Lawrence Massacre of August 1863. Inside War is not without issue. Fellman conceded that the book was a reaction to American involvement in Vietnam. As a consequence, it often skewed the political motivations of pro-Confederate guerrillas and presented them as bloodthirsty criminals. But as a counterbalance to numerous neo-Confederate accounts of the irregular war in the borderlands, it cleared the proverbial elephant from the room and left other scholars of guerrilla violence free to branch out geographically and methodologically. For that reason, Inside War is still a must read.

The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War (University of North Carolina Press,  2001) by Victoria Bynum

2001) by Victoria Bynum

Owing to its Confederate bona fides, Mississippi might have seemed an unlikely place to find an internal guerrilla conflict, but that’s precisely what Victoria Bynum writes about in The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War. The book outlines an insurgency within an insurgency: After Mississippi seceded from the Union, a multiracial cohort of disgruntled Jones County residents effectively tried to secede from their Confederate state. (The story was made into a 2016 feature film with that title starring Matthew McConaughey, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, and Mahershala Ali.) Bynum is among the best writers the field of Civil War history has to offer; her vivid narration of the war to control Jones County marked a high point in the study of southern Unionists and their victimhood. The Free State of Jones also documents that women, African Americans, and even children were direct, active participants in the guerrilla warfare experience, and Bynum reminds us how deeply local outbreaks of guerrilla violence were rooted in the mainstream politics of secession and slavery.

A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2009) by Daniel Sutherland

A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2009) by Daniel Sutherland

In addition to having the biggest spoiler title, Daniel Sutherland’s A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War is something of an anomaly compared to the other books here. Rather than continuing the trend of researching irregular violence at the community, county, or even state level, Sutherland pulled back and reassessed the overall influence of guerrillas on the outcome of the Civil War. The book moves through the divided country one region at a time and gradually pieces together a national tapestry of irregular violence. From raiding and bushwhacking to looting, ambush, espionage, and outright massacre, A Savage Conflict was the first work of its kind to attempt sizing up guerrilla warfare in toto—let alone to document how endemic violence across the homefront influenced morale, swayed political decisions, disrupted supply lines, and altered troop movements. Collectively, these influences played a decisive role in how the Union won the war. Perhaps more than revealing the national scope of guerrilla warfare, Sutherland threw light on the fact that for myriad Americans, irregular conflict was a pretty regular thing.

Bushwhackers: Guerrilla Warfare, Manhood, and the Household in Civil War Missouri (Kent  State University Press, 2016) by Joseph Beilein

State University Press, 2016) by Joseph Beilein

Given the backstory on guerrilla literature, it may or may not be fitting that this list of best books on the subject concludes with a Missouri-centric title. Joseph Beilein’s Bushwhackers: Guerrilla Warfare, Manhood, and the Household in Civil War Missouri can be a book both about Missouri and about the broader guerrilla experience in other locations. It blueprints what made waging guerrilla war possible in Missouri. Through his extensive social and genealogical research into the kinship networks of Confederate bushwhackers, Beilein illustrates how the female relatives of men in the bush (wives, mothers, cousins, daughters, aunts, and sisters) served as de facto quartermasters in a war waged from within and upon literal households. This concept of “household war” is undoubtedly applicable to other pockets of irregular conflict; it delivers a model for studying the logistical and material components of bushwhacking while also offering new angles for understanding why and where people chose to fight as guerrillas in the first place.

Matthew Christopher Hulbert is an Elliott Assistant Professor of History at Hampden-Sydney College. He is the author of The Ghosts of Guerrilla Memory: How Civil War Bushwhackers Became Gunslingers in the American West (University of Georgia Press, 2016), which won the 2017 Wiley-Silver Prize.

This article appeared in the Fall 2021 (Vol. 11, No. 3) issue of The Civil War Monitor.