Kurz & Allison’s depiction of the Battle of Chancellorsville

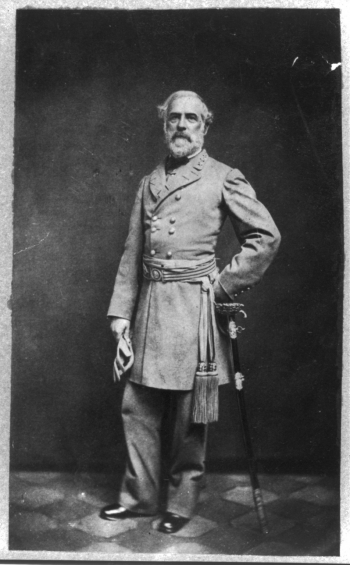

In the aftermath of his army’s defeat at Gettysburg, General Robert E. Lee welcomed a brother of Secretary of War James Seddon to Army of Northern Virginia headquarters. Curious as to the public’s opinion of his performance, Lee asked him, “[F]rom what you have observed, are the people as much depressed at the battle of Gettysburg as the newspapers appear to indicate?” The Seddon brother told Lee that he believed that the newspaper reports were accurate. Lee then proceeded to expound on “how little value is to be attached to popular sentiment in such matters” by offering a rather surprising assessment of the Confederate victories at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. “At Fredericksburg we gained a battle,” Lee remarked, “inflicting very severe loss on the enemy in men and material; our people were greatly elated—I was much depressed. We had really accomplished nothing; we had not gained a foot of ground, and I knew the enemy could easily replace the men he had lost…. At Chancellorsville we gained another victory; our people were wild with delight—I, on the contrary, was more depressed than after Fredericksburg.”(1)

How could this be? What kind of twisted thinking could lead Lee to judge Chancellorsville—where he had half the manpower of the Union army but, through bold and skillful generalship, was able to force it to retreat from the field—so harshly?

A fundamental modern military principle is to “continuously assess the operational environment and the progress of operations.” And the first step toward a successful assessment is deciding what to measure and how to measure it. Commanders often find two concepts helpful in assessment: measures of performance, or MOPs (which ask the question, “Are we doing things right?”), and measures of effectiveness, or MOEs (which ask, “Are we doing the right things?”). Those who understand the difference know that joint forces need to “do the right things” (succeed at MOEs) to achieve objectives, not just “do things right” (succeed at MOPs).(2)

A superb example of someone confusing the two took place in April 1975 in Hanoi. “You know you never defeated us on the battlefield,” an American military officer told a North Vietnamese officer. “That may be so,” the North Vietnamese officer replied, “but it is also irrelevant.”(3) Victory on the battlefield can be an MOE, if it helps achieve the war’s strategic ends. If not—or worse, if it is counterproductive to that effort—a battlefield victory is little more than an MOP.

Obviously, Lee and his command did many things right in the Chancellorsville Campaign. He correctly identified Major General Joseph Hooker’s turning movement as the Union main effort and then compelled the Federals to give up terrain they seized during the campaign by forcing them back across the Rappahannock River. But was reclaiming that terrain an MOE, and therefore sufficient cause for the celebration that followed? Or was Lee correct in seeing it as merely an MOP? In other words, did the Army of Northern Virginia do things right but not do the right things?

Answering these questions, of course, requires identifying what the right things were. While the Confederacy could have been justifiably proud of its military performance in 1862, its strategic situation was badly deteriorating by the spring of 1863. The Union army had made up for the losses in manpower it had suffered the previous year, the Union blockade was tightening its grip, and Confederate arms were on the brink of a catastrophic defeat along the Mississippi River. However satisfying the December 1862 victory at Fredericksburg may have been to others in the Confederacy, Lee knew that his country did not need another bloody battle along the Rappahannock River that resulted in the Union army merely retracing its steps to its camps. Indeed, Lee had been “much depressed” by Fredericksburg, while in Washington, President Abraham Lincoln had looked over the results of the battle—one in which no one could deny that their generals had performed poorly—and found a silver lining, musing: “[I]f the same battle were to be fought over again, every day, through a week of days, with the same relative results, the army under Lee would be wiped out to its last man, the Army of the Potomac would still be a mighty host.”(4)

Yet a far more damaging battle is what Lee got in May 1863 at Chancellorsville. It ended with the Federals re-crossing the Rappahannock River after inflicting over 12,000 casualties on Lee’s army, a casualty rate of over 20 percent. The cost to the Union army came to about 17,000—by no means insignificant, but still less than 15 percent of the Federal force. Making matters worse, Lee had thrown just about every unit in his army into the fight, while nearly three entire Union corps had been only minimally engaged. If the course of the war in the East was ultimately decided by how long it took until the Army of Northern Virginia was no longer combat effective—if that was an MOE—then Lee was absolutely correct in his woeful assessment of the campaign.

Of course, the counterpoint is to consider Lee’s alternatives. He certainly could have been less aggressive in his response to Federal movements. (There is little doubt that Lee was fortunate that Hooker chose to retreat when he did, which denied Lee the opportunity to launch what would have certainly been a bloody—and probably futile—final assault against an impregnable Federal line on May 6.) Still, given Lee’s options and Hooker’s clear determination to not repeat the mistake of Fredericksburg by launching pointless attacks on entrenched Confederate positions, it is difficult to see the Confederates accomplishing as much as they did with a more cautious battle plan.(5)

Alternately, Lee could have taken the option to, in Hooker’s immortal words, “ingloriously fly,” giving up the Rappahannock line and falling back to the North Anna River. Such a move would have undoubtedly spared his army the heavy losses at Chancellorsville and might have provided him a better logistical situation. Yet any possible material advantages must be weighed against the loss of the moral effects won by the Chancellorsville Campaign. There is little doubt that Lee was wrong to, in his remarks to Seddon, deprecate the value of public opinion “in such matters.” In a conflict such as the Civil War, which Lincoln so accurately described as “a people’s contest,” public opinion could matter as much as, if not more than, material effects.(6) The fact that southerners “were elated” over the outcome at Chancellorsville was a genuine positive result of the campaign for the Confederacy.

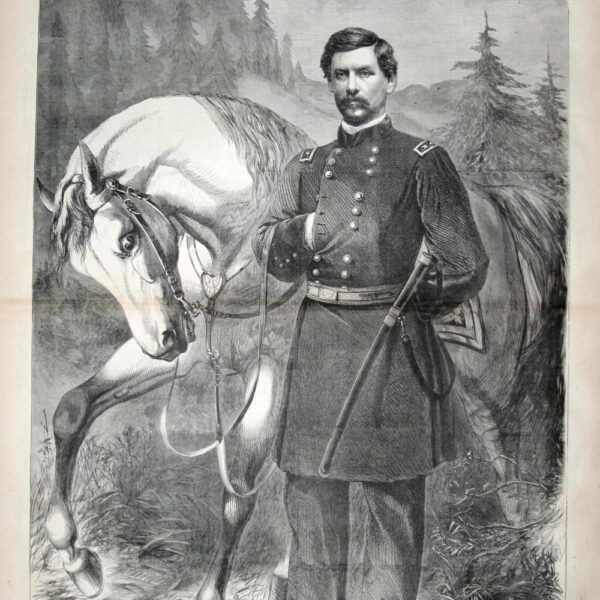

Union general Joseph Hooker

Even if Lee’s narrow range of options means the MOP–MOE concept does not compel a reassessment of the Confederate army’s performance, we can still scrutinize the Federals’ actions through that lens. If holding ground was the MOE, they were clearly ineffective. But if maintaining terrain was only an MOP and other metrics—such as progress toward achieving the Union’s strategic goal of grinding down the Confederate army until it could no longer resist—are used for measuring effectiveness, then Fighting Joe Hooker did rather well. He did not repeat the mistakes of Fredericksburg, and he made the Confederates pay a far greater price for the terrain they reclaimed than what it was worth. Indeed, according to the guidance Hooker received from his superiors in Washington on taking command of the Army of the Potomac, his conduct during the Chancellorsville Campaign very much met their MOE. On January 31, 1863, General-in-Chief Henry Halleck forwarded to Hooker a message he had sent a few weeks earlier to his predecessor that he stated “embodies my views in regard to the duty of the Army of the Potomac.” In that letter, Halleck declared, “The great object is to occupy the enemy … and to injure him all you can with the least injury to yourself.” In this, Halleck was echoing the views of President Lincoln, who pointedly endorsed the letter and declared shortly before the Chancellorsville Campaign began that, “I do not think we should take the disadvantage of attacking him in his entrenchments; but we should continually harass and menace him, so that he shall have no leisure.”(7)

Thus, if one looks beyond the MOP of ground occupied and instead to an MOE such as relative loss rates, the Federals’ performance at Chancellorsville suddenly looks much better. While Hooker certainly committed errors and missed opportunities, he did meet his superiors’ mandate to “injure” and “harass” Lee. Hooker got his army across the Rappahannock smoothly and then took up a strong defensive position that enabled him to inflict massive casualties on the Confederates. He then re-crossed the river, giving up ground that was of no particular value.(8) Regardless of the Confederate army’s performance, this was certainly not an effective game for Lee to play—nor one that he wanted to repeat. Looking back with an MOP and MOE method of assessment, Lee’s gloomy and unconventional view of the battle is understandable.

Ethan S. Rafuse is professor

of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. His publications include Robert E. Lee and the Fall of the Confederacy, 1863–65 (2008) and a forthcoming guide to the Manassas battlefields.

This article appeared in the Spring 2013 issue of The Civil War Monitor.