Library of Congress

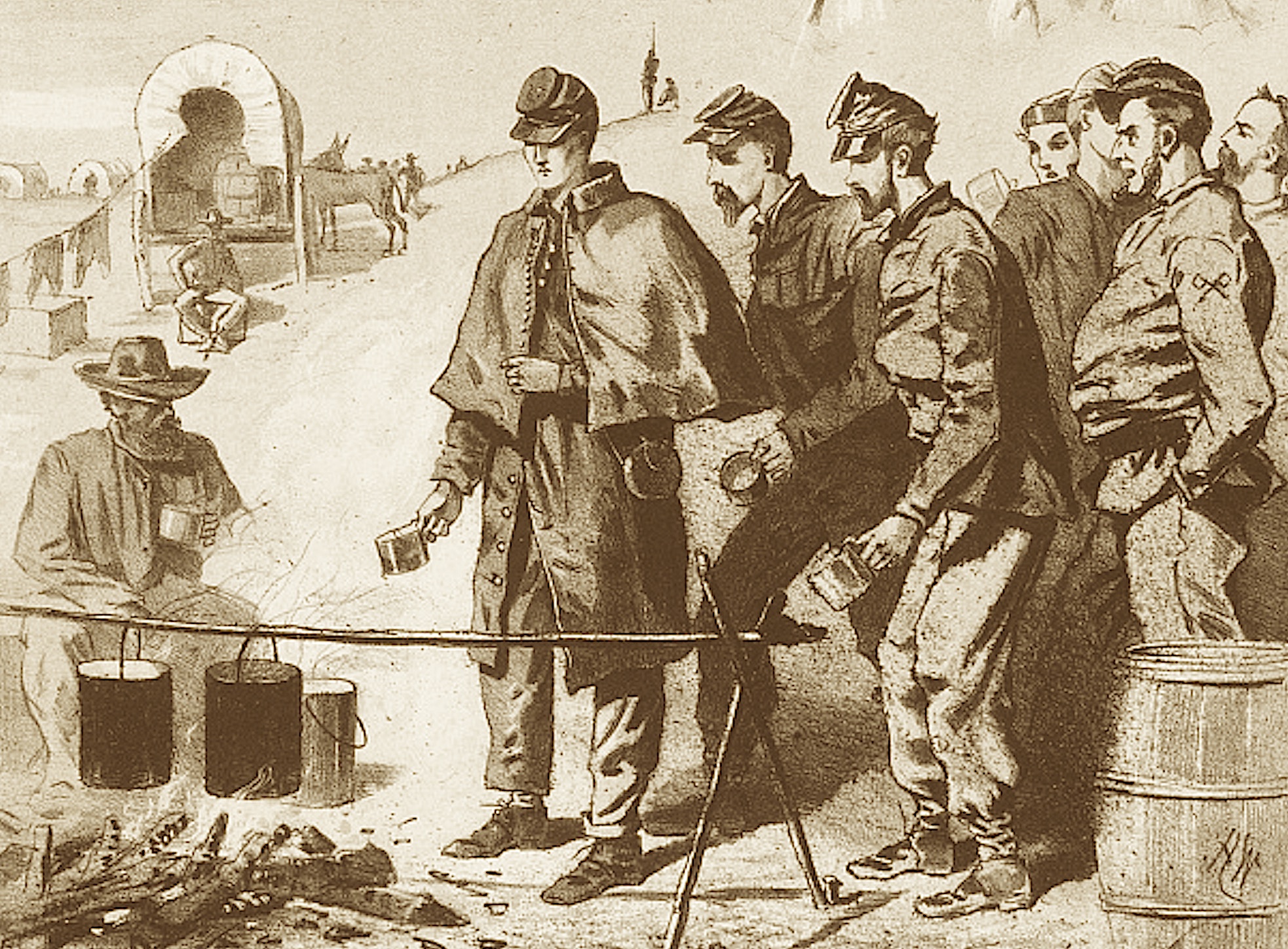

Library of CongressWinslow Homer’s illustration “The Coffee Call” depicts Union soldiers waiting their turn for a cup of the popular beverage.

In March 1863, The Medical and Surgical Reporter, a Philadelphia journal, published the fifteenth installment in a series of communications from Union surgeon J. Theodore Calhoun, who reported on the variety of medical issues that affected the men of the Army of the Potomac. Often, Calhoun’s reports included bits about the nature of army life and the behaviors of soldiers. Below is an excerpt from his March report on a truth of military life that he had learned quickly during his time in the military: soldiers loved—and absolutely depended on—coffee.

Coffee is the soldier’s luxury, deprived of which he imagines himself the worst used individual that he is capable of conceiving. On a march, for convenience sake, the coffee and sugar are mixed together. Every man carries his tin cup or can for making his coffee, and he would sooner think of leaving his musket than the cup wherein to make his coffee.

The new regiments come out very well supplied with cups, but the old soldier disdains buying a cup, and manufactures a much better one for himself. Taking one of the cans in which fruits and vegetables are preserved (and which every sutler has a full assortment of), he cuts the top entirely out, and with a piece of wire, cut from some abandoned or destroyed telegraph line, he makes of it a handle (technically a “bail”) and his coffee pail is complete. The moment a halt is made the soldier commences making his coffee. Some water from his canteen, or neighboring brook or spring, is soon boiling briskly over a little fire of glowing coals. Upon the boiling water he pours his coffee and sugar, and by the time the coffee has settled to the bottom, and the sugar is dissolved, the beverage is ready for use. Coffee drinking is a passion with soldiers, amounting almost to a mania. A five minutes halt on a march, and a soldier must have his coffee. If he straggles behind and escapes the provost guard, he sits down, and contented, makes his coffee. If he strays off the road to some of the “hospitable mansions” by the road side, his first request is to be allowed to make a little coffee in the fire-place, and on halting for the night, no matter how tired he may be, he could not by any possibility, spread his blanket until he had enjoyed his cup of hot coffee.

The immediate use of coffee is productive of much of the diarrhoea of camp, but taken in reasonable quantities, I doubt if any such effect would be produced. Attempts have been made to substitute tea for coffee, but with no success. Soldiers think more of their coffee than all the rest of the nation. They do not like tea, and though, when issued in lieu of coffee they will use it, yet they grumble not a little at the substitution.

Source:

J. Theodore Calhoun, “Rough Notes of an Army Surgeon’s Experience During the Great Rebellion, No. 15” The Medical and Surgical Reporter (Vol. 9, March 21, 28, 1863).

Related topics: food and drink