Nurse Mary Livermore

Shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War, Mary Livermore, a 40-year-old native of Boston, volunteered to work for the United States Sanitary Commission in hopes of being of assistance to the Union war effort. She soon became an agent at the organization’s Chicago branch (where she would eventually be promoted to co-director), in which capacity she organized a variety of aid socities and fundraisers and inspected a number of military hospitals in Illinois and bordering states. Livermore encountered countless sick and wounded soldiers during her hospital visits, one of whom left an enduring impression on her and her occasional traveling companion, fellow nurse Mary Stafford, as evidenced by the following story she included in her memoir of the conflict, My Story of the War (1888). Livermore, who was active in the women’s suffrage movement after the war, died in 1905 at age 84. Safford would attend medical school and become a physician in the postwar years, focusing on caring for impoverished women and girls; she died in 1891 at age 56. The following excerpt comes from Chapter VIII of Livermore’s memoir:

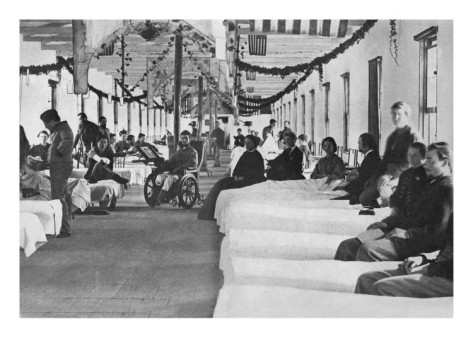

My second visit to the Cairo hospitals, was made in company with Miss Mary Safford, then a resident of Cairo. She commenced her labors immediately when Cairo was occupied by our troops. If she was not the first woman in the country to enter upon hospital and camp relief, she was certainly the first in the West. There was no system, no organization, no knowledge what to do, and no means with which to work. As far as possible she brought order out of chaos, systematized the first rude hospitals, and with her own means, aided by a wealthy brother, furnished necessaries, when they could be obtained in no other way.

Surgeons and officers everywhere opposed her, but she disarmed them by the sweetness of her manner and her speech; and she did what she pleased. She was very frail, petite in figure as a girl of twelve summers, and utterly unaccustomed to hardship. She threw herself into hospital work with such energy, and forgetfulness of self, that she broke down utterly before the end of the second year of the war. Had not her friends sent her out of the country, till the war was over, she would have fallen a martyr to her patriotic devotion….

Every sick and wounded soldier in Cairo, or on the hospital boats, at the time of my visit, knew her and loved her. With a memorandum book in one hand, and a large basket of delicacies in the other, while a porter followed with a still larger basket, we entered the wards. They had a vastly more comfortable appearance than on the occasion of my first visit. The vigorous complaints entered against them, and, more than all, a realistic description of them that found its way into the Chicago papers, had wrought reforms. The baskets were packed with articles of sick-diet, prepared by Miss Safford and labeled with the name of the hospital and number of the ward and bed.

Nurse Mary Safford

The effect of her presence was magical. It was like a breath of spring borne into the bare, white-washed rooms—like a burst of sunlight. Every face brightened, and every man who was able, half raised himself from his bed or chair, as in homage, or expectation. It would be difficult to imagine a more cheery vision than her kindly presence, or a sweeter sound than her educated, tender voice, as she moved from bed to bed, speaking to each one. Now she addressed one in German, a blue-eyed boy from Holland—and then she chattered in French to another, made superlatively happy by being addressed in his native tongue.

The baskets were unpacked. One received the plain rice pudding which the surgeon had allowed; there was currant jelly for an acid drink, for the fevered thirst of another; a bit of nicely broiled salt codfish for a third; plain molasses gingerbread for a fourth; a cup of boiled custard for a fifth; half a dozen delicious soda crackers for a sixth; “gum-drops” for the irritating cough of a seventh; baked apples for an eighth; cans of oysters to be divided among several, and so on, as each one’s appetite or caprice had suggested. One man wished to make horse-nets, while his amputated limb was healing, and she had brought him the materials. Another had informed her of his skill in wood-carving, but he had no tools to work with, and she had brought them in the basket….

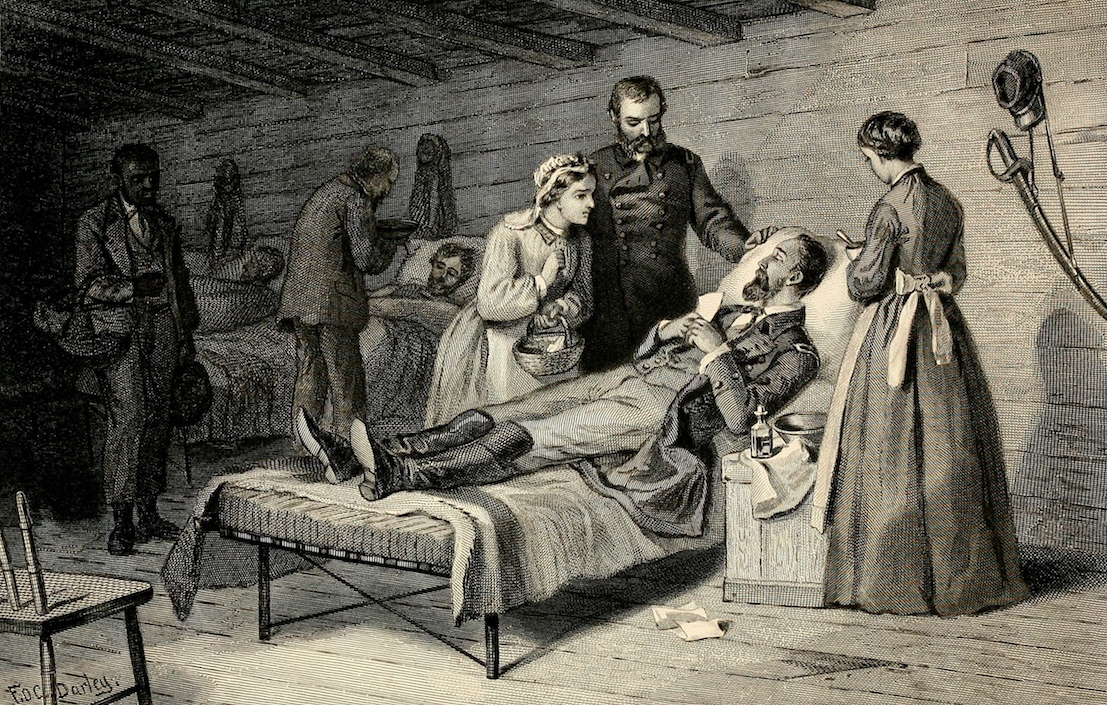

As we were making the tour of the hospitals, a tall and stalwart man was brought in on a stretcher, who had been shot the night before on one of the gunboats stationed at Island Number Ten. It was not a dangerous wound apparently—only a little hole in the left side, that I could more than cover with the tip of my smallest finger—but the grand-looking man was dying.

“Can we do anything for you?” one of us inquired, after the surgeon had examined him, and he had been placed in bed.

“Too late! too late!” was his only reply, slightly shaking his head.

“Have you no friends to whom you wish me to write?”

He drew from an inside vest pocket—for his clothing was not removed—a letter, enclosing a photograph of a most lovely woman. “You wish me to write to the person who has sent you this letter?”

He nodded slightly, and feebly whispered, “My wife.”

Nurses Mary Livermore and Mary Safford tend to a dying soldier in a military hospital at Cairo, Illinois, a scene Livermore described in her postwar memoir of the Civil War.

Bowing her head, and folding her hands, Miss Safford offered a brief touching prayer in behalf of the dying man, bending low over him that he might hear her softly spoken words. Her voice faltered a little, as she remembered in her prayer the far-absent wife, so near bereavement. “Amen!” responded the dying man, in a distinct voice, and then we left him with the attendant, to minister to others. Lifting the photograph, he gazed at it earnestly for a few moments, pressed it to his lips, and then clasped it in both hands. When I returned to his bed, some twenty minutes later, he was still looking upward, his hands still clasping the photograph, and his face was irradiated with the most heavenly smile I have ever seen on any face. I spoke to him, but he seemed not to hear, and there was a far-away look in the gaze, as though his vision reached beyond my ken. I stood still, awestruck. The wardmaster approached, and laid his finger on the wrist. “He is dead!” he whispered.

The duty of writing the widowed wife was assigned me, and I took the letter and photograph. Ah, what a letter was that which the dying man had placed in my hands! He had evidently not replied to it, for it had been only just received, and had not the worn look of having been carried long in the pocket. It was from his wife, informing her husband of the death, on the same day, of their two children, three and five years old. It was the letter of a superior woman, who wrote nobly and tenderly, hiding her own grief, in her desire to comfort her husband.

“I do not feel that we have lost our children,” thus she wrote; “they are ours still, and will be ours forever. Their brief life was all sunshine, and by their early departure they are spared all experience of sorrow and wrong. They can never know the keen heartache that you and I must suffer at their loss. It must be well with them. Their change of being must be an advance, a continuance of existence on a higher plane. And some time, my dear Harry, we shall rejoin them. I sometimes fear, my darling, that you may meet them before I shall. Their death has taken from me all the fear of dying, which, you know, has so greatly distressed me. I can never fear to follow where my children have led. I have an interest in that other life, whatever it may be, an attraction towards it, of which I knew nothing before. Oh, my dear Harry, do not mourn too much! I wish I were with you, to share with you, not alone my hope, but the great conceptions of that other life which have come to me.”

I enclosed to the bereaved wife her own letter and photograph taken from the dead hands of her husband, and told her all I knew of his death. A correspondence ensued, which stretched itself along the next three years. In the depth of her triple bereavement, the saddened woman found comfort in the belief that her children and husband were united. “I sometimes believe the children needed him more than I,” was her frequent assertion….

Related topics: medical care