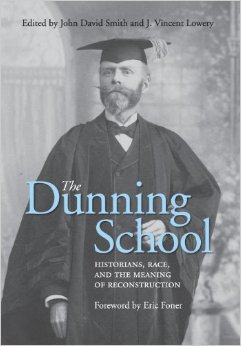

The Dunning School: Historians, Race, and the Meaning of Reconstruction edited by John David Smith and J. Vincent Lowery. The University Press of Kentucky, 2013. Cloth, ISBN: 0813142253. $40.00.

It seems remarkable that a book such as this one has not been done before. As the title of this volume suggests, John David Smith and J. Vincent Lowery have edited a collection of historiographical essays on several of the scholars (though not all of them) who comprised what historians of Reconstruction have long known as “the Dunning school.” Named for the Columbia University historian William Archibald Dunning, this school of thought — which dominated the historical profession during the first half of the twentieth century and retains a formidable hold on the popular imagination today—advanced what was in essence a white supremacist interpretation of Reconstruction. This interpretation lent scholarly justification to the Jim Crow system that prevailed in the South (and, in certain respects, the nation at large) until it was eventually discredited by the “revisionist” scholarship of the last half-century.

It seems remarkable that a book such as this one has not been done before. As the title of this volume suggests, John David Smith and J. Vincent Lowery have edited a collection of historiographical essays on several of the scholars (though not all of them) who comprised what historians of Reconstruction have long known as “the Dunning school.” Named for the Columbia University historian William Archibald Dunning, this school of thought — which dominated the historical profession during the first half of the twentieth century and retains a formidable hold on the popular imagination today—advanced what was in essence a white supremacist interpretation of Reconstruction. This interpretation lent scholarly justification to the Jim Crow system that prevailed in the South (and, in certain respects, the nation at large) until it was eventually discredited by the “revisionist” scholarship of the last half-century.

The anthology features ten essays, each of which examines a particular “Dunningite” historian. The book includes an introduction by John David Smith and a foreword written by Eric Foner. All of the essays share a basic structure. Each provides a biographical overview of its subject before situating the subject’s work within the larger historical and historiographical contexts.

Each of the Dunningites was committed to the pursuit of “scientific” history and to telling what he or she believed to be the true story of Reconstruction. Although one can speak of a more or less coherent “Dunning” school, these essays also show a surprising diversity of thought, from the relatively liberal viewpoints of C. Mildred Thompson (the only woman under study here), Paul Leland Haworth, and (to a lesser extent) James Wilford Garner, to those of the stanchly reactionary (and racist) William Watson Davis, Charles W. Ramsdell, and J. G. de Roulhac Hamilton, the father of the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina.

Surprisingly, Dunning did not demand that his students adhere to a particular interpretation, instead allowing them considerable intellectual autonomy; in certain instances, he appears to have had little influence on his students’ intellectual development. Almost all of the Dunningites under study here were native southerners (though Dunning himself was a native of New Jersey), several of whom returned to their region upon completing their graduate studies. Most of them (Dunning included) sought to counter the northern, triumphal view of the Civil War era that they believed had become the standard interpretation by the early twentieth century.

In certain cases – in particular Michael W. Fitzgerald on Walter Lynwood Fleming and Paul Ortiz on William Watson Davis – the essayists reveal how their subjects’ often incisive and nuanced examinations of the Civil War years gave way to ham-handedly simplistic formulations regarding Reconstruction. It is almost as though these eminently reasonable scholars, despite their devotion to scientific history, seemed to lose all sense of reason when they began talking about Reconstruction – especially racial matters.

This raises an intriguing problem. It is axiomatic that the main task of the historian is to understand and not to pass moral judgment on people who lived in the past. Today’s notions of right and wrong, it is frequently noted, are simply different from those of previous times. This idea makes perfect sense. And yet for the purposes of this volume, this approach also begs the question of how otherwise honorable and decent men and women, who ostensibly dedicated themselves to rationale, scholarly discourse, could have been so utterly blinded by the racism that was pervasive in their society. To be sure, today’s historians must refrain from judging people in the past— even when those people were historians themselves. We are aware today, even if we do not entirely understand it, of the overwhelming power of socialization in shaping individual thought and behavior. Still, these were people who, among all others, ought to have known better — especially since, as both Smith’s introduction and Foner’s foreword remind us, alternative ways of looking at Reconstruction were readily available at the time.

Indeed, other than perhaps a degree of repetition—which is understandable in such a work, where each author probably felt obligated to observe that the views under study have been discredited—the only possible criticism one could make of this fine volume is that, in certain of the essays, the authors seem to bend over backwards not to make value judgments. Given the subject matter and its profound consequences, a stronger assessment might not have been entirely out of order. The reader at times senses almost an implicit attempt to rehabilitate the individuals under study, and even a mild annoyance with the current state of Reconstruction historiography. Still, Smith and Lowery are to be commended for putting together such an excellent collection of essays. All scholars of Reconstruction will find this long-overdue book invaluable.

John C. Rodrigue is the Lawrence and Theresa Salameno Professor at Stonehill College and the author of Reconstruction in the Cane Fields: From Slavery to Free Labor in Louisiana’s Sugar Parishes, 1862-1880.