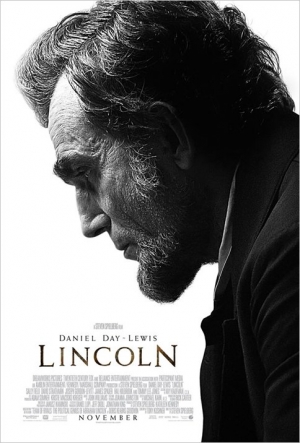

Lincoln (2012) directed by Steven Spielberg. Length: 149 minutes. Premiere: November 16, 2012.

Movies can negatively shape popular perceptions of history. Birth of a Nation (1915) helped lead to the revival of the Klan. Gone with the Wind (1939) still shapes many peoples’ comprehensions of slavery. The Patriot (2000) provided a false understanding of the soldiers and tactics of both sides during the Revolutionary War. Often, history instructors must spend class time debunking and criticizing Hollywood depictions of America’s past and they skeptically approach any historical film ready to hammer away at inaccuracies or distortions. As a result, many people have come to believe that professional historians simply hate all historical movies. Thus when an exceptional film, like Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln comes along, scholars should be out front extolling its many virtues instead of criticizing it for not being the film that it was never intended to be.

Movies can negatively shape popular perceptions of history. Birth of a Nation (1915) helped lead to the revival of the Klan. Gone with the Wind (1939) still shapes many peoples’ comprehensions of slavery. The Patriot (2000) provided a false understanding of the soldiers and tactics of both sides during the Revolutionary War. Often, history instructors must spend class time debunking and criticizing Hollywood depictions of America’s past and they skeptically approach any historical film ready to hammer away at inaccuracies or distortions. As a result, many people have come to believe that professional historians simply hate all historical movies. Thus when an exceptional film, like Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln comes along, scholars should be out front extolling its many virtues instead of criticizing it for not being the film that it was never intended to be.

Lincoln is not the story of the long and multifaceted process of emancipation. It is difficult to imagine any film comprehensively and cogently covering such a complex topic in 2.5 hours. Yet, some academics have leaped to criticize Lincoln for not providing a more complete understanding of the various players and events involved in the eradication of slavery in the United States. Such a movie would need to detail the long struggle of both black and white abolitionists, cover the Radical Republicans and the Confiscation Acts, and focus on enslaved blacks courageously fleeing to northern lines. It would also need to highlight the vital role of the Union army in the process of emancipation and demonstrate how military developments made the Emancipation Proclamation necessary. Combining all these elements into one movie would require too many characters and subplots to follow and would result in a disjointed and confusing mess, exhausting viewers with an enormous running time (Gods and Generals comes to mind). And yet, we would still not have a comprehensive understanding of emancipation.

Thankfully, Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner did not attempt to make such a movie. They did not even film all aspects of their source book, Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals. Instead, the primary focus is on only one minor part of the emancipation story, President Lincoln’s role in engineering the 13th Amendment through the House of Representatives in early 1865 with bipartisan support. His effort required skillfully uniting the various wings of his own party and securing at least 20 Democratic votes. Here Spielberg gets at the heart of Goodwin’s thesis by accurately portraying Lincoln as a masterfully shrewd politician employing any means necessary (the specifics of which are largely fictionalized, but entertaining and accurate in spirit) to pull together a disparate political coalition. This tightly focused narrative arc provides the film with high drama, light comedy, and an exhilarating climax. Those who have studied Civil War congressional debates will be especially pleased with the film’s accurate and entertaining depiction of these discourses. To the film’s credit, it becomes clear that northern racism was often as virulent as southern. We may quibble about some of the details, but in the end, the film’s accuracy is praiseworthy, even if narrowly focused on a topic that requires mainly depicting the machinations of a few white men.

Those who have long studied the Civil War and developed an affinity for Lincoln can not help but feel that watching Daniel Day-Lewis’s stunning performance is likely the closest they will ever come to knowing what it was like to be in the great man’s presence, charmed by his folksy stories, and mesmerized by his quiet brilliance. The film’s subplots provide accurate glimpses into Lincoln’s often troubled relationship with Mary Todd (played effectively by Sally Field) and their inconsolable grief over losing one child and facing the prospect of seeing another march off to war.

Yet the film does much more, showing that slavery’s end was only the first step in our nation’s long and tortured path to racial justice. The opening scene graphically depicts African Americans engaged in the most aggressive and important thing they could do to end slavery—courageously risking their lives in combat to destroy the Confederacy. Various characters refer to the black troops, suggesting the amendment to be an act of justice for their military service and contemplating what citizenship rights, if any, their actions have secured once the war concludes. As other reviewers have commented, certain scenes in which Lincoln and African Americans interact seem painfully awkward and forced. Yet any conversation between whites and blacks about race would have been uncomfortable, with both sides attaching different meanings to the war and its impact. In one brilliantly written scene, Lincoln and radical congressmen Thaddeus Stevens (played by scene stealing Tommy Lee Jones) discuss the future, and in doing so foreshadow the disagreements that will lead to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments, and the ultimate failures of Reconstruction. Emancipation, the film accurately demonstrates, only created new and more vexing questions.

Lincoln is highly entertaining and extraordinarily well acted by the entire cast, and is now debatably the finest Civil War movie we have (audiences have been applauding it as the end credits begin to scroll). Unlike many other big budget historical epics, viewers will see a largely accurate account of events. There is not even a slight attempt to glorify or romanticize the Confederacy and its defense of slavery, and this alone is pleasing in a Civil War movie. Because of the film’s concentration on the 13th Amendment, there are vital elements of the emancipation story not depicted. African American agency is largely absent, (with the highly significant exception of black military service), but so too are the important contributions of a vast array of others. The film relegates Radical Republican dynamos Benjamin F. Wade and Charles Sumner to just one scene, for example, and they appear simply as passive members of Stevens’ entourage. Nevertheless, we must judge Lincoln for what it was meant to be, and thus praise it for getting its story right. Hopefully, Hollywood will soon provide us with other aspects of slavery’s destruction, even if those stories appropriately place Abraham Lincoln on only the fringes of their particular narrative.

Glenn David Brasher is a history instructor at the University of Alabama, and the author of The Peninsula Campaign & the Necessity of Emancipation; African Americans and the Fight for Freedom (2012).