Library of Congress

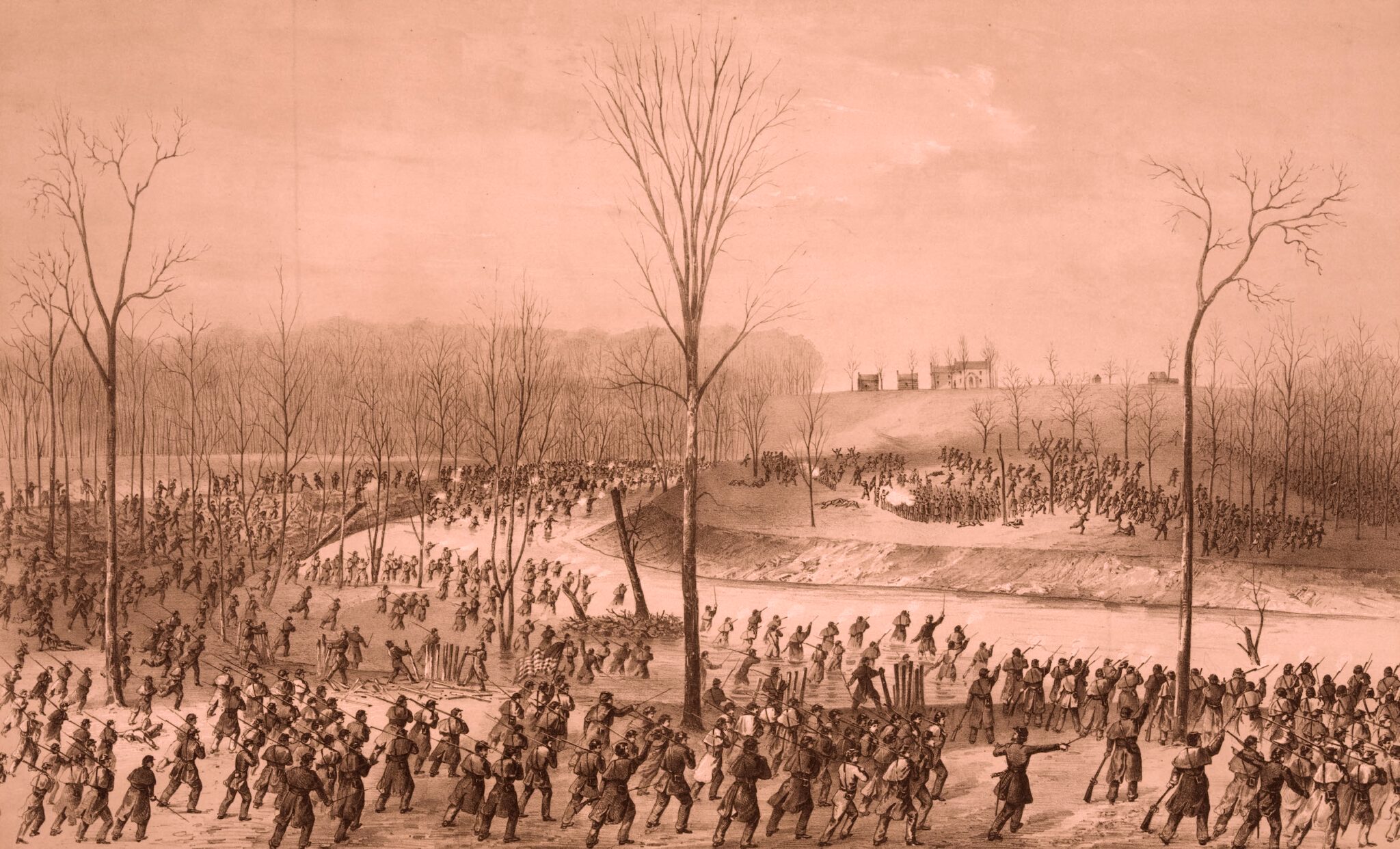

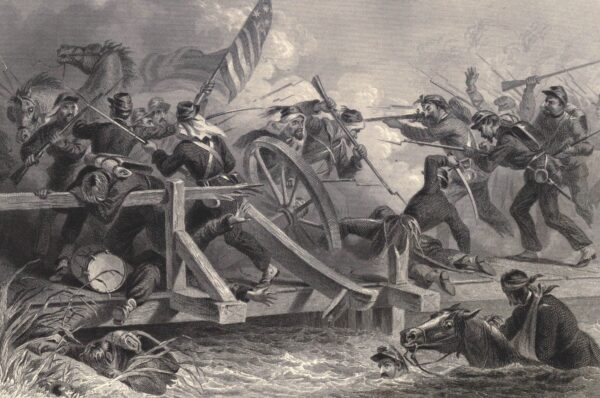

Library of CongressIn this wartime lithograph, Union soldiers fight their way across Stones River during the Battle of Murfreesboro on January 2, 1863.

What does the mighty Mississippi have in common with the Potomac and Stones rivers? According to those who carve monuments and write local histories, on at least one occasion, all of them ran red with blood during the Civil War. The same is true for smaller hydrologic features as well, including lesser tributaries (creeks at Sharpsburg and Cloyd’s Mountain, runs at Gettysburg and Cold Harbor) and ponds at Shiloh and Chickamauga. (Some Civil War aficionados “translated” Chickamauga to mean “Bloody River,” though the name is simply a phonetic spelling of Tsikamagi, the Cherokees who occupied the area into the 1830s.)

Perhaps the best testament, or memorial, to these legends can be found between the 14th hole and the 15th tee on a golf course occupying Lowes Island in the Potomac, just upriver from the nation’s capital. A remarkable tablet there overlooks the broad waterway and reads, “Many great American soldiers, both of the North and South, died at this spot, ‘The Rapids,’ on the Potomac River. The casualties were so great that the water would turn red and thus became known as ‘The River of Blood.’ It is my great honor to have preserved this important section of the Potomac River!” The text is followed by the signature of the club’s owner, Donald Trump—and it has been repeatedly disputed by historians, who point out that no significant combat took place within 10 miles of the island.

This column is dedicated to using science to provide insights into military history and historical controversies, and “rivers of blood” certainly seem an appropriate topic. Former President Trump has claimed that “numerous historians” told him (or, later, “his people”) the story of the blood-red river. The result is a debate among historians involving the intersection of history and the natural world, including the reported occurrence of a physical phenomenon that critical scientific reasoning can test. Let’s wade in.

Two soldiers were reportedly killed by civilians on Lowes Island near the beginning of the war, hardly enough bloodshed to turn even the smallest stream red. Nonetheless, the question remains as to how many men would need to bleed out into a large river to turn it red? This is a surprisingly complicated question, requiring both quantification (How much water is flowing in the river and how fast is it flowing? What volume of blood can one wounded soldier contribute to the staining?) and qualification (When has a river ever turned “blood red,” not just showed signs of being tinted?). Consideration of these factors collectively produces some interesting conclusions. (Spoiler alert: The Lowes Island plaque will someday need revision to reflect historical accuracy.)

The New York Times

The New York TimesThe “River of Blood” Monument at Trump National Golf Club on Lowes Island.

To start this analysis, we’ll use the flow parameters surrounding the Potomac just north of Washington, D.C., followed by consideration of the hydrologic characteristics of the larger river, the Mississippi, and the smaller one, the Stones. The most significant factor in changing the color of a river is its discharge, or the volume of water flowing past a particular point along the river (say, a golf course) in a given unit of time. River and stream discharge is measured in cubic feet per second (cfs), cubic meters per second, or gallons per minute. The second noteworthy factor is the velocity of a river, because even if you can turn it red, the taint will quickly move downriver. Nobody ever wrote about a river that ran red with blood “for a second or two.”

Discharge and velocity are directly related, as water volume and velocity both increase during flooding. For normal flow stages along this stretch of the Potomac, the river has a discharge of around 10,000 cfs and a velocity of 3 or 4 mph (283,000 liters per second and 1.3 meters per second). Both values can vary tremendously, but this provides us with a starting point for further analysis.

The average human body contains 5 liters of blood, so a dead soldier can contribute around a gallon and a half of that bright red liquid. A wounded soldier could offer no more than two liters—40% of blood volume—before his wound would be mortal. In summary, the pertinent empirical values for turning a river red are a discharge of untainted water (283,000 l/s) traveling at 1.3 m/s, with each individual corpse contributing up to 5 liters of blood. What needs to be clear is the number of bleeding bodies required to turn the moving water red. Accepting as fact that as the blood-to-river-water ratio increases, so does the color saturation, the question at the heart of this analysis becomes: How much blood is necessary to transform naturally clear water into a fluid that could indisputably be characterized as “blood red”?

Previous literature on this subject is both scarce and all over the place. A ratio of 1:4 blood to water is often discussed, which seems almost ridiculously high—you would need thousands of bleeding bodies to color a backyard swimming pool red. To get a more realistic answer, I spent an afternoon in my research lab mixing different quantities of blood into stream water, surveying students (most of whom seemed in future to avoid my classes) about when they could detect a red tint and when the water would definitely be classified as “blood red” in color.

A red tint could be clearly detected at a blood concentration just above 2% (20 liters of blood in approximately 980 liters of water). At 4% blood, the water was clearly red with blood. This indicates that one man, who bled out into a body of still water, could turn 125 liters of fluid red. A company of dead and severely wounded soldiers could turn red a typical backyard pool or a similar-sized body of standing water on a battlefield.

Back to the Potomac. To turn one small portion of that river blood red for one second would require about 2,250 profusely bleeding corpses. And this transformation of one short swath across the river would quickly move downstream. For the river to truly “run red” a longer duration of flow would be needed, say a 100-foot stretch of river that lasts for a little over 20 seconds before passing by.

For this scenario you would need more than 50,000 corpses to be bleeding out fully along the 100-foot shoreline. The closest significant combat occurred 11 miles upriver at Balls Bluff near Leesburg, where 85 men were killed and around 400 were wounded—maybe enough to turn a tiny tributary red for a few moments, but certainly not enough to color the Potomac.

Based on this analysis, it is clear that the Mississippi River, with a discharge an order of magnitude greater than the Potomac, never ran red. The Mississippi is so massive that if all the soldiers killed in the Civil War had bled out along a short portion of the shoreline, it wouldn’t tint the fast-moving water red for even a few seconds. To turn the river blood red for more than a few seconds would require all the fatalities from all American wars combined.

But before we discard the “river of blood” trope, let’s look at the other end of the volume spectrum: Stones River. Stones is small enough in water volume and velocity, and the battle fought there was bloody enough, that a red river is not out of the question. With a discharge of around 7,000 l/s, only around 1,200 actively bleeding fatalities, or 3,000 bleeding casualties, would be needed to turn one 100-foot length of Stones River blood red. This would represent only about one-third of the men killed or wounded during that battle. This would require the unlikely event that all these men would have needed to end up—still bleeding, remember—in the river. That did not discourage at least one author from giving their history of the battle the title Stones River Ran Red.

Finally, and importantly, many smaller, lower discharge streams and creeks, and stationary bodies (i.e., lakes and ponds) absolutely could have turned red with blood. There can be little doubt that the historical accounts of, for example, Bloody Pond at Shiloh were accurate, given the ratio of wounded and dying (and thirsty) men to this volume of still water.

The ahistorical plaque on Lowes Island will probably remain. There are several claims on the monument that are worth disproving, including the island’s battle history, the geographic location on the river—it is far upstream from “the rapids”—and the notion that the river once ran red with blood. While critical reasoning could wash away any of those fallacious claims, this column has chosen to sink just one.

Scott Hippensteel is professor of earth sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he focuses on coastal geology, geoarchaeology, and environmental micropaleontology. He has written three books about using science to illuminate military history: Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat (University of Georgia Press, 2023), Myths of the Civil War: The Fact, Fiction, and Science behind the Civil War’s Most-Told Stories (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), and Rocks and Rifles: The Influence of Geology on Combat and Tactics during the American Civil War (Spring Nature, 2018).

Thank you for scientifically disproving yet another bombastic claim.