The War with the South, Vol. 1 (1862)

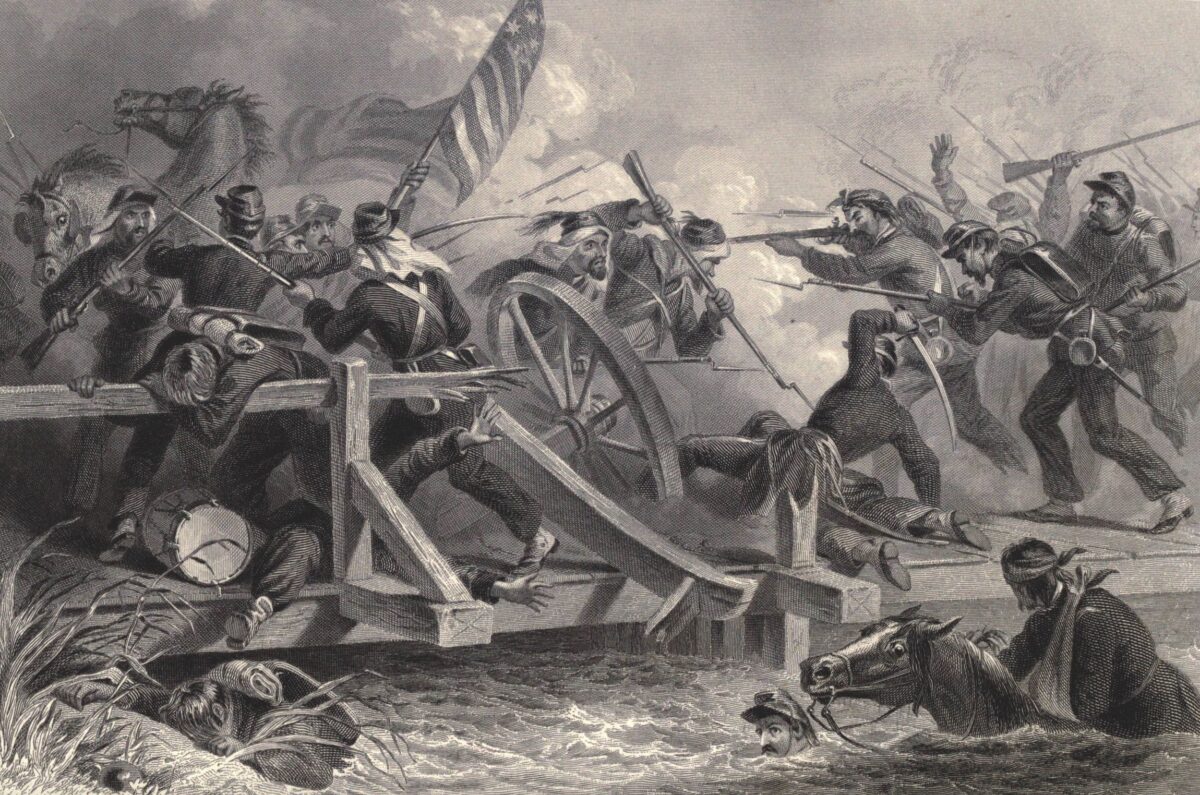

The War with the South, Vol. 1 (1862)F.O.C. Darley’s illustration of the Battle of Bull Run

In its October 12, 1861, issue, The Scientific American reprinted a brief article that had recently appeared in the Philadelphia newspaper North American. In it, an editor at the North American wrote up his notes of a discussion with a Union veteran of the Battle of Bull Run, which had been fought the previous July. The editor’s goal: to inform his readers—including potential army enlistees—what the experience of combat was like in the months-old Civil War. It appears below, in full.

How a man feels when in battle is a question that our volunteers have doubtless frequently asked themselves. We yesterday stumbled upon a volunteer on furlough, who first smelt powder at Bull Run. During an hour’s chat with him he gave us a very good general idea of the way in which a man feels when under an enemy’s gun. Our friend didn’t claim to be especially courageous. He placed due value upon the integrity of the American eagle, but enlisted mainly because he had no other employment at the time. He did camp duty faithfully, and endured the hardships of long marches without any special grumbling. That he dreaded to confront the enemy he freely admits. While willing at any time to kick a bigger man than himself under justifiable provocation, he disliked the idea of the sudden sensation imparted by a bayonet thrust in the abdomen, while only second to this was his horror of being cut down with a rifle ball like an unsuspecting squirrel.

When his regiment was drawn up in line he admits his teeth chattered and his knee pans rattled like a pot-closet in a hurricane. Many of his comrades were similarly affected, and some of them would have lain down had they dared to do so. When the first volley had been interchanged, our friend informs us, every trace of these feelings passed away from him. A reaction took place, and he became almost savage from excitement. Balls whistled all about him, and a cannon shot cut in half a companion at his side. Another was struck by some explosive that spattered his brains over the clothes of our informant, but, so far from intimidating, all these things nerved up his resolution. The hitherto quaking civilian in half an hour became a veteran. His record shows that he bayoneted two of his rebel enemies and discharged eight rounds of his piece with as decisive aim as though he had selected a turkey for his mark. Could the entire line of an army come at the same time into collision, he says there would be no running except after hopeless defeat.

The men who played the runaway at Bull Run were men who had not participated in the action to any extent, and who became panic stricken where, if once smelling powder in the manner above described, they would have been abundantly victorious. In the roar of musketry and the thundering discharge of artillery there is a music that banishes even innate cowardice. The sight of men struggling together, the clash of sabers, the tramp of cavalry, the gore-stained grass of the battle-field, and the coming charge of the enemy dimly visible through the battle smoke—all these, says our intelligent informant, dispel every particle of fear, and the veriest coward in the ranks perhaps becomes the most tiger-like. At the battle of Bull Run the chaplain of one of the regiments, a man of small stature and delicate frame, personally cut down two six feet grenadiers in single combat. If these things are so—and we incline to think they are—the best cure for cowardice is to crowd a man into a fight and there keep him. The fugitives from Bull Run were men who imbibed panic before it could have reached them.