John Banks

John BanksMonument to a New York brigade at the site of the Battle of Wauhatchie, fought in October 1863 as part of the Chattanooga Campaign.

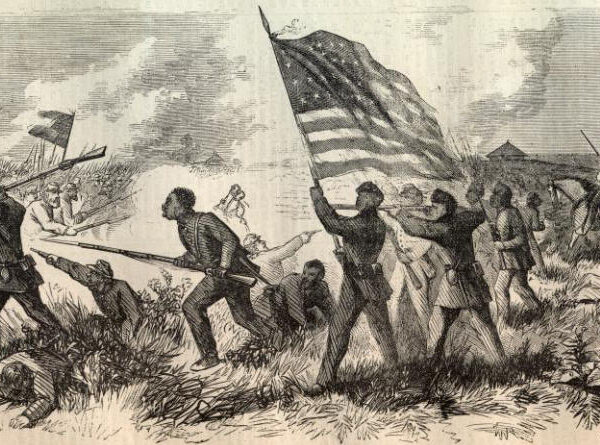

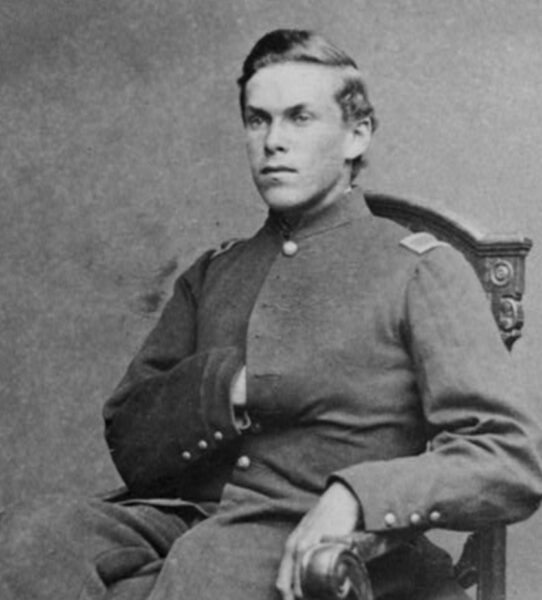

Earthmovers and developers long ago carved up the Wauhatchie battlefield where Lieutenant Edward Ratchford Geary of Independent Battery E, Pennsylvania Light Artillery (known as Knap’s Battery) took a bullet in the head that killed him on October 29, 1863. He was but 18, and the first-born son of U.S. Army Major General John White Geary, who commanded soldiers fighting near the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad track in this rare night battle in Tennessee.

“Poor dear boy, he is gone, cut down in the bud of his usefulness,” the general wrote about his son, already a veteran of the Civil War battles at Cedar Mountain, Antietam, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.1

“Where did he die?” I ask.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressEdward Geary

“Right about over there,” says our excellent guide, Anthony Hodges, a retired dentist who lives nearby, high atop Raccoon Mountain overlooking Chattanooga.

He points to a slight rise roughly 75 yards beyond a New York brigade monument and a chain-link fence—to where dozens of Edward Geary’s comrades fell too. A one-story commercial building stands on the site that was Lookout Valley farmland back then.

Above us, we are blessed with a deep-blue sky. Far over our shoulders looms magnificent Lookout Mountain. Fifteen yards behind us, parallel to Wauhatchie Pike, is a high railroad embankment. From behind it, the guide explains, Confederates poured fire onto the Union troops that chilly night.

Nearby, a train clacks, chugs, and groans. Traffic on the Wauhatchie Pike is slight this Sunday afternoon. Downtown Chattanooga is only a few miles away.

Less than a mile away, near Interstate 24, a trucking business stands where Hodges hunted for Civil War relics years ago. “That was covered with winter quarters during the war,” he says of the site. When Hodges was a kid, he explored the remains of Civil War huts that covered the hillsides in the area.

In the opposite direction, beyond a fast-food restaurant, convenience store, and a hotel off Brown’s Ferry Road, stands the only other monument to the unheralded battle, honoring the divisions of New York troops who fought at Wauhatchie. Travelers zooming by on I-24 can catch a glimpse of it if they know where to look.

But I’m not here for the monument. I’m here for the boy, Edward Geary, who had enlisted in the Union army at 16. At 17, he commanded a section of Knap’s Battery at Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg.

Despite his youth and connection to high rank, Geary had earned the respect of his comrades. I wonder what would have become of this bright officer had he not died in a 3-hour battle at godforsaken Wauhatchie, a junction on a railroad line that snaked through the foreboding Lookout Valley.

Modern intrusions be damned, I try to imagine the fear Geary and his comrades must have felt as they staved off surprise attacks near midnight from a brigade of South Carolinians commanded by Colonel John Bratton. I try to imagine, too, the demonic Rebel yell, the crackle of musketry and the boom of Federal cannon on an inky black night.

“Shoot the gunners,” the Confederates screamed from behind the embankment that at one point divided the combatants.

“It was a fearful hour,” a U.S. soldier recalled about the attack. “Our hearts almost stood still.”2

“The night was livid with sudden sheets of flame, blazing along the line of rebel infantry while the shells were crashing above the heads of our gallant boys, bewildered by the sudden attack,” another recalled.3

Later, Union troops rolled a cannon on the Rebels’ side of the embankment and opened up with canister, forcing the enemy to abandon their position.

“Three times the enemy made an attack, boldly charging on [General] Geary’s center, for the purpose of capturing his artillery, and each time they were driven back signally and with heavy loss,” a New York Herald correspondent wrote. “The fighting by our men was of the coolest and bravest kind. Every attempt to outflank our small force was checked at once.”4

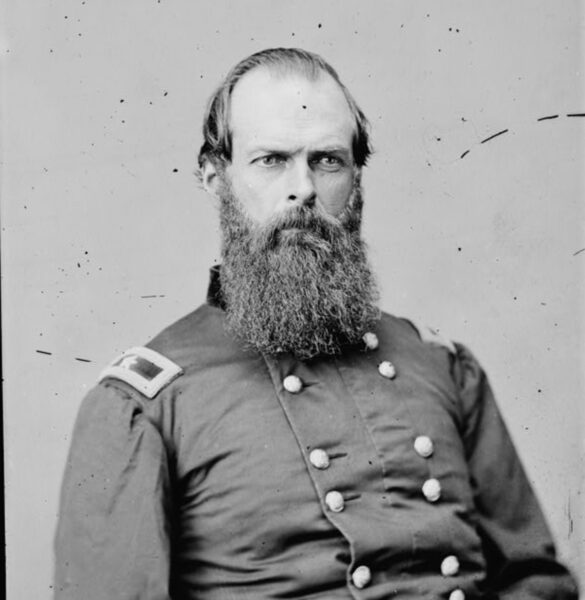

Library of Congress

Library of CongressJohn W. Geary

During the fighting, the din unnerved dozens of U.S. Army mules, prompting a stampede toward enemy lines and creating confusion among the Rebels.5 A Union soldier later wrote The Charge of the Mule Brigade—based loosely on the 1854 poem The Charge of the Light Brigade.

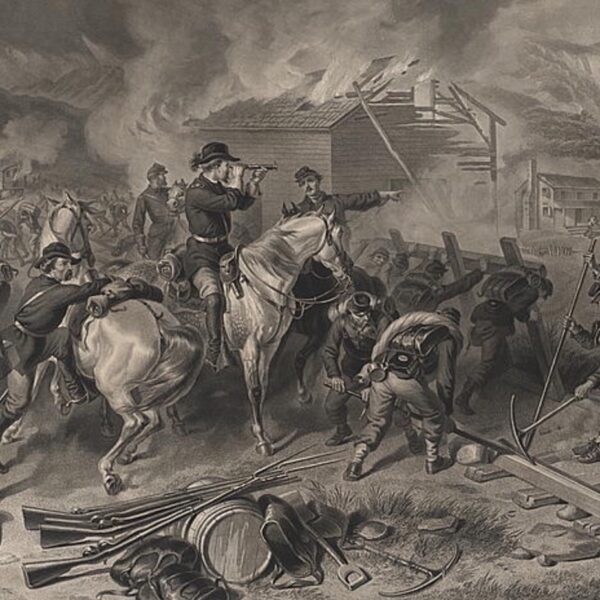

The result of the battle allowed Ulysses Grant to establish a supply line, “The Cracker Line,” for his garrison in Chattanooga and then lift Army of Tennessee commander Braxton Bragg’s siege of the city.

Compared to Cedar Mountain, Antietam, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg, Wauhatchie was a minor fight. No more than 600 casualties resulted: 356 Confederates in Bratton’s brigade, 216 from among the 1,600 U.S. soldiers.

But no matter the size of the battle, their loved ones mourned the dead just the same. The death of his son shattered John Geary, who found Edward’s body amid the corpses and horses and bullet-marked caissons and limbers.

“The men respecting his sorrow stood at a distance in silence while he communed with his grief,” a New York soldier recalled.6 Another soldier remembered Geary—who stood 6-feet-4-inches and weighed upwards of 250 pounds—trembling with emotion over his son’s death.7

“Another victim of this accursed rebellion,” a soldier wrote of Lieutenant Geary.8

Ever the overbearing father, the general had shepherded Edward’s rapid rise and was said that day to have carried his commission as captain.

General Geary had his son’s remains transported to a cemetery in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, to be buried beside his mother, Margaret Ann, who had died in 1853.

“I have gained a great victory,” Geary wrote his second wife, Mary, “[b]ut oh! how dear it has cost me.”9

John Banks is author of A Civil War Road Trip of a Lifetime and two other Civil War books. A longtime journalist (The Dallas Morning News and ESPN), he is secretary-treasurer of The Center for Civil War Photography and a board member of the Save Historic Antietam Foundation and Battle of Nashville Trust. He lives in Nashville with his wife, Carol.

Notes

1. A Politician Goes to War: The Civil War Letters of John White Geary, ed. William Alan Blair (University Park, PA, 1995), 131.

2. The True Democrat, York, PA, September 4, 1866.

3. The Pittsburgh Commercial, November 11, 1863.

4. The Pittsburgh Commercial, November 9, 1863.

5. John Billings, Hardtack and Coffee, or, The Unwritten Story of Army Life (Boston, 1888), 295.

6. George K. Collins, Memoirs of the 149th Regt. N.Y. Vol. Infantry (Syracuse, NY, 1891), 200.

7. The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 38, 1876.

8. The Harrisburg Telegraph, July 12, 1866.

9. A Politician Goes to War, 135.