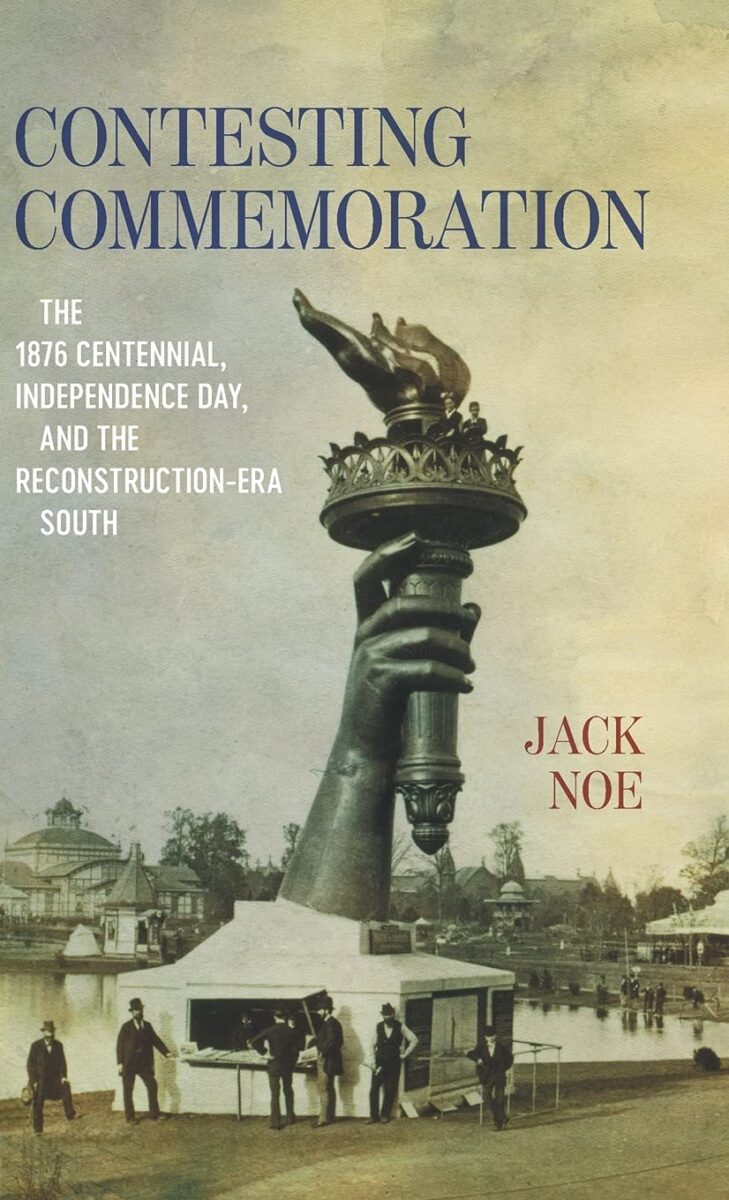

In 1876, about one in five Americans attended the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, which celebrated the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence with an event similar to a world fair. Event organizers used the Centennial to flaunt American technological success and emphasize reunion after the Civil War. Jack Noe draws on the incredible scope of the Centennial to examine how a diverse group used the event to find meaning in their identity as Americans after the Civil War.

Through a source base that consists mostly of newspapers, Noe argues in Contesting Commemoration that the Centennial “was a locus of political, racial, and sectional antagonism” (178). Noe explores the complex realities of post-war reunion and claims that white Southerners “alternately shunned or engaged selectively and conditionally” with the patriotic celebration, while African Americans “embraced the opportunity to stake their claim to full agency and citizenship” (13). Neither group fit comfortably in the Centennial’s themes of American “national belonging,” and Noe reveals the contested nature of Revolutionary memory at the end of Reconstruction (3).

In his chronological narrative about the Centennial, Noe’s first two chapters cover Independence Days in the South from the Antebellum to Reconstruction eras, when political tensions surrounding the Fourth took root. For example, on pre-Civil War Fourths of July, white Southerners celebrated “the slaveholding republic that they felt was intended by the founders,” and many continued to celebrate the day throughout the Civil War (17, 25). Alternatively, African Americans and abolitionists used the day to “promulgate a philosophy that undermined the bedrock of Southern life and to demand liberation” (17). Noe’s consistent juxtaposition of African American and white interpretations of Independence Day demonstrates the significance of the commemorations as ways to either adopt or contest American identity.

Because of the political nature of commemoration, Americans harshly debated the 1876 Centennial. Chapters three and four cover these political debates and contextualize them within the politics of Reconstruction. By focusing on the debates about the event and how people interpreted it, Noe sheds light on the political flexibility of commemorations.

Noe also dives into the connections between the Centennial and post-war reunion, arguing that it “proved problematic for the [white] South,” which understood it as a “Yankee” celebration that highlighted themes of patriotic pride and industrialism (58). In the third chapter, Noe discusses the political role of women in the Centennial, who supported reconciliation through fundraising for the event. While most scholars focus on women’s importance in promoting Lost Cause narratives after Reconstruction, Noe offers a slightly earlier time frame when white women “acknowledged a sisterhood of sorts with their northern counterparts” and used their shared loss to carve a path towards reconciliation (86). However, Noe also points to an anti-reconciliation sentiment among many Southern women. Expanding on the positions of these women and how their ideas developed into the 1880s would have allowed Noe to connect their stories to the establishment of organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

In Contesting Commemoration, Noe is not concerned with the actual design and events of the Centennial fair, but rather “how Americans actually experienced the event and inscribed it with meaning” (3). Chapter five reveals how different Americans experienced the event itself and remains focused on sectional tensions found at the Centennial. It especially focuses on African Americans, who were largely excluded from the event, yet desired to use it as an opportunity to display their citizenship and role in the Revolutionary era. Noe’s approach draws from an abundant base of scholarship on Civil War memory, and he frequently engages with this scholarship.

Noe returns to his central theme of politics and commemoration in the final chapter, where he discusses local commemorations of the Fourth of July in 1876 across the South. Noe argues that the South resumed its celebration of Independence Day once Reconstruction governments had officially ceased to exist, which was due to the “political conditionality” of commemorations (156). Incorporating a brief description of the controversial election of Rutherford B. Hayes allows Noe to connect politics and commemoration. He continually highlights the partisan notes in accounts of Fourth celebrations. Like most of his narrative, his vignettes about local commemorations give depth to the actors behind the events and show just how contested each celebration really was.

Noe’s work elucidates the need for scholars of Civil War memory to fully address the way post-Civil War reunion and reconciliation changed memory of the Revolutionary era. More work should be done on post-Reconstruction commemorations of the Revolutionary period; Noe’s engaging Contesting Commemoration provides a framework for researching other Revolutionary-era commemorations.

Meredith Barber is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at Boston University with research interests in race, Virginia, and memory of the American Founding and Revolutionary periods.

Related topics: memory