The old court house at Charles Town, Jefferson County, Virginia, where John Brown was tried for treason.

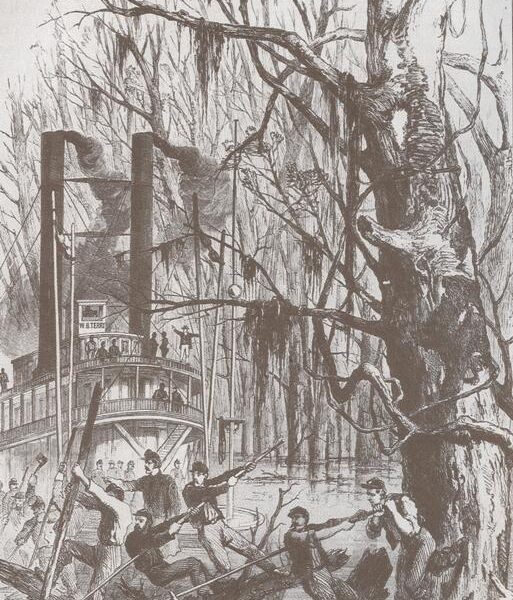

Long before the tumult and rage in Charlottesville last year over the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee from a city park, and a fear that white supremacists and antifa militants would turn any future confrontation into a bloodier event there, Virginia was braced for an even deadlier showdown in the fall of 1859. Thousands of troops had poured into Jefferson County, on orders to repel with force any “invaders.”

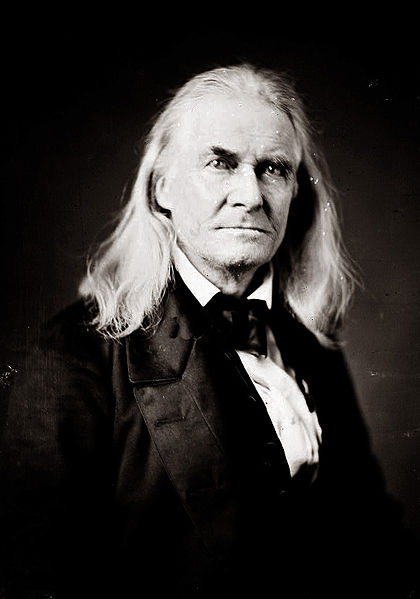

And two old men would emerge as “martyrs” to their causes that were as diametrically opposite from one another as could be imagined. Their names were John Brown and Edmund Ruffin.

Less than a week before John Brown was to hang for treason, Virginia Governor Henry Wise and the mayor of Charles Town, Thomas C. Green, agreed on the best way to preserve the peace in the court house: Be suspicious of all strangers—day or night, demand residents stay in their homes, close down businesses, and stop all trains from entering Jefferson County.

Troops on the streets and surrounding roads were there to enforce their edict. Passwords were the order of the night and day.

Among the strangers caught up in the frenzy of suspicion were Wise himself when he forgot the day’s password; Colonel Robert Baylor, who had commanded Virginia’s militia when Brown attacked Harpers Ferry; and Edmund Ruffin, famed agronomist, the “missionary of disunion” then without honor in his home state.[i]

* * *

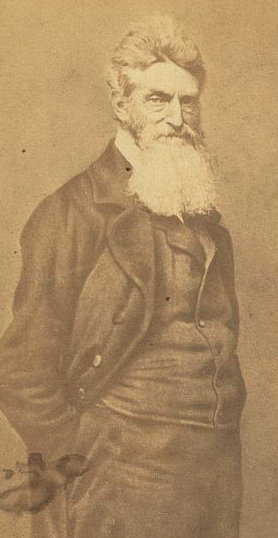

In many ways, the 65-year-old Ruffin, the son of a Virginia planter of the second tier along the James River, was the mirror image of the 59-year-old Brown. The rough-hewn Brown was born in Connecticut and grew up in Ohio in a family with deep Puritan roots that commingled with absolute abolitionism.

Instead of mellowing with age, both men’s positions calcified over slavery as the years passed.

While Brown at six feet was about four inches taller than Ruffin, their visage was strikingly similar, memorable—stern, and hawkish.[ii]

* * *

Long before he left his thousand-acre Hanover County plantation on November 26, 1859, Ruffin preached “no unprejudiced mind can now admit the equality of intellect of the two races.” Thomas Jefferson’s “All men are created equal” was anathema to him. He was comfortable in the intellectual orbit of slavery being the proper nature of the world even if not divinely ordained.[iii]

John Brown

Brown wholeheartedly committed himself to abolition, with the fervor of the “New Lights” evangelism of the Reverend Jonathan Edwards Jr. Brown was at a rare juncture of politics and religion even for New England. On the other hand, Ruffin, nominally an Episcopalian, was most often a religious doubter. He carried a particular dislike for Protestant rigidity. “There is nothing in iniquity ascribed to Satan that is worse than the Calvinistic creed ascribes to the Almighty & all-merciful God.”[iv]

Certainly not a religious proselytizer, Ruffin truly was an intellectual disciple of Thomas Dew and Nathaniel Beverly Tucker, the hardest of the hardliners in Virginia when defending slavery. He found dozens of kindred spirits a few hundred miles to the South. The governor of South Carolina, a man as interested in modern farming techniques as he was and as devoted to slavery as the William and Mary coterie, wanted Ruffin to attempt an agricultural survey of the state. As he wandered around the Palmetto State, Ruffin felt at ease with the men whose values and politics he shared.

Here and in his own mind, John C. Calhoun was a paragon; Henry Clay and Daniel Webster and all their works were despicable; and Andrew Jackson was detestable.

South Carolina became his second home.[v]

Most troubling in the days after Brown’s arrest in October to Virginia slaveholders were the plantation fires being reported across the state, even on his children’s holdings. Ruffin thought the blazes probably set by slaves likely at some white man’s instigation, another precursor of servile rebellion.

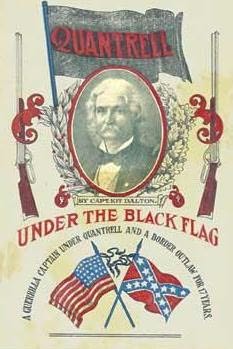

But crazed abolitionists, as they proved in Kansas, were capable of striking anywhere at any time with guns, hatchets, nooses, pikes, and firebrands.

Were there other Browns loose in the Virginia countryside?[vi]

To many contemporaries in the slaveholding states, even in the days following Brown’s failed attack, Ruffin was seen in all matters political as a man who wielded a pen “dipped in passion.” In reality, he was the missionary for a new generation of like minds. They were James Henry Hammond, the “Cotton is King” senator; Robert Barnwell Rhett, former congressman and fiery Charleston newspaper editor regarded as an extremist even in South Carolina; and William Lowndes Yancey, one-term Alabama congressman who with Ruffin founded the League of United Southerners to “precipitate the Cotton States into a revolution.”[vii]

The intensity Ruffin felt for that revolution was such that even in Rhett’s Charleston Mercury, a Ruffin piece was headlined, “Cassandra—Warnings.”[viii]

His biographer, Betty L. Mitchell, wrote, “Unknown to Ruffin, another old man, who also fancied himself a somewhat of a prophet, was preparing at that very moment to fulfill ‘Cassandra’s Warnings’ and arouse Ruffin as he’d never been aroused before.”[ix]

To Ruffin in late fall of 1859, abolitionists were wolves to be exterminated—if they dared to try to save Brown and his murderers. That’s why he set out on a solitary pilgrimage for the “seat of war” on that late November morning.[x]

* * *

Edmund Ruffin

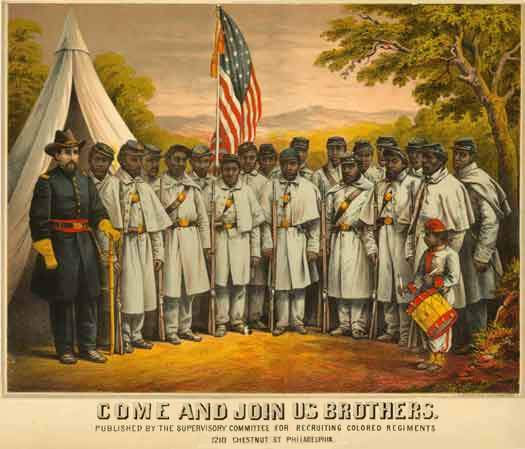

“Everything in the shape of business” was “suspended” in Charles Town. Even church services were affected. The military—more than a thousand militiamen from across the state and cadets and officers from the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington—was increasingly in charge of events. They were backed up by federal soldiers dispatched from Fortress Monroe under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee.[xi]

When he arrived in Jefferson County and discovered no civilians would be allowed to attend this “atrocious criminal’s” end, Ruffin immediately played on his connections with the senior military officer present, Colonel Francis H. Smith, the superintendent of the Virginia Military Institute.

Their relationship dated back at least a decade, deepened with Smith’s push to establish an agricultural school in Lexington. Ruffin’s stature as the leading figure in state agricultural circles made contact between the two natural.

The two talked frankly about the danger Charles Town faced from outside agitators. Eventually, Ruffin got to the point: He wanted to be physically present at the execution, like his old Petersburg friend, Hugh Nelson. Nelson had talked his way into that city’s militia to witness the hanging. For whatever reason, Smith agreed. Ruffin could stand with the cadets. What harm could it do?[xii]

The old man with a “worse than useless left hand” now marched out to hobnob with the lights of the courthouse. With a five-foot long pike with a two-foot blade in hand bearing the legend “Sample of the Favors for us by our Northern Brethren,” a gift from the arsenal’s superintendent, he lustily preached sectional separation from the perfidious North to a passersby. Because of Brown’s mayhem, his new crusade was to unite slaveowner with non-slaveowner, conservative with extremist to his political views. Now under a cloud himself, Baylor, the commander on the scene at the time of the raid, thought the old man was spouting treason and needed to be forcibly removed from the street.[xiii]

By then, however, Ruffin was untouchable and welcomed by men of stature in the courthouse, like Andrew Hunter, the special prosecutor in Brown’s treason trial.

Ruffin, an extremely well-read man in many fields, and Hunter, the dignified lawyer with keen political instincts in Democratic politics, dined together several times, obviously finding each other’s company congenial. Ruffin also talked at length with Lewis Washington, the great-grandnephew of the first president, who was taken at gunpoint by Brown’s men and survived the assault on the firehouse that netted Brown. Israel Green, the heroic Marine officer who clubbed Brown over the head with his sword in the assault that freed Washington and the other hostages, met with Ruffin when he returned to Jefferson County for the execution.[xiv]

On the early morning of December 2, Ruffin accompanied a VMI patrol on its “grand rounds” to ensure that no deluded abolitionists were skulking about. When he returned to his room about four, he was tired but exhilarated. Not wanting to sleep through the muster call, he laid himself down uncomfortably on a sofa to pass the time until duty called.[xv]

Now in mid-morning on a mild late fall day, squads of cadets were manning two small artillery pieces aimed at the gallows under the command of Thomas Jackson. The main body of cadets were in formation between the artillery pieces about 50 yards from the rear of the gallows. All told, there were about 800 militiamen lining up at their assigned spots. Among their number was a young actor who argued his way into a Richmond infantry company as it was boarding a train. His name was John Wilkes Booth. Cavalry troopers rode the field’s perimeter to keep out any civilians.[xvi]

Standing in the cadets’ ranks was Ruffin, wearing an institute overcoat and carrying a musket as best he could. His previous days as a militiaman, during the War of 1812 (in which he saw no combat), were but gauzy memories.

Ruffin knew the cadets viewed him as “a very amusing and perhaps ludicrous” character. As they waited for more than a hour, the charmer engaged the young men and won them to his side.[xvii]

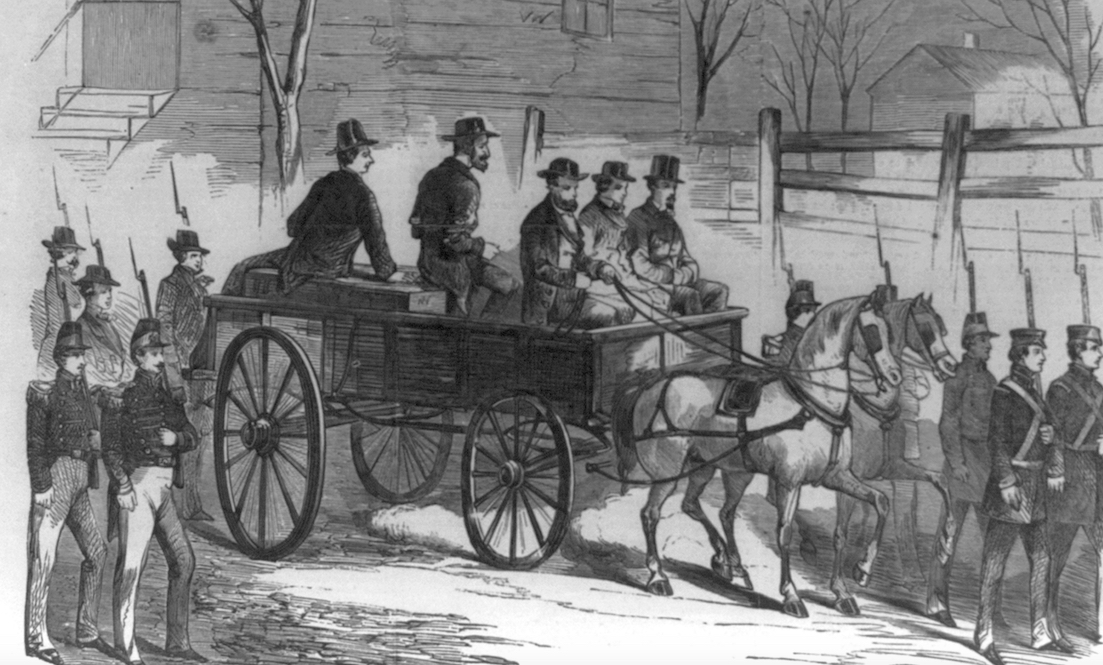

While still in the jail, Brown again angrily rejected any ministrations from clergy tainted by slavery. The very sight of a Catholic priest shortly after his capture sent the badly wounded Brown into a fury. Now entering the grounds, he swayed with the wagon’s motion and patted his knees as he had done during the trial. He sat straight up “as if to set to the soldiers an example of a soldier’s courage.”[xviii]

John Brown, sitting atop his coffin, is transported by wagon to the site of his execution.

Petersburg militiamen, many known by Ruffin, stood close around Brown as a body guard until he was assisted by two men from the wagon. “With firm step and erect from, he strode past Jailor, Sheriff, and officers, and was the first person to mount the scaffold steps.” On the platform, Brown made no speech.[xix]

That he said no prayers, had no minister standing behind reading sacred scripture left Jackson, a fierce Calvinist in his own right, convinced Brown’s soul would soon be in hell. Ruffin didn’t speculate in his diary on Brown’s afterlife.[xx]

Brown’s ankles and arms were bound. A white hood was drawn over his head. He stood “erect and motionless, like a statue.”[xxi]

At last, the sheriff “severs the rope with his hatchet, the trap falls with a horrid screech of its hinges, and the unfortunate man swings off into the air.” J.T.L. Preston, second in command of the cadets, broke the silence: “So perish all such enemies of Virginia; all such enemies of the Union.”[xxii]

After about 20 minutes, military and civilian doctors converged to determine if Brown was dead.

When Brown’s body was taken to the jail for further examination, Ruffin and the cadets were dismissed from further service. Ruffin was physically and emotionally drained by the events of the past 12 hours. When he looked out the next day from his window, there was a steady cold drizzle, mixed with hail and snow. Because of the elevation “at night, the earth was covered with sleet.”[xxiii]

Ruffin’s unfinished business came to him in a rush then. It was not enough for him to witness the hanging, write about it in his diary, or later publish essays for readers all over the South. He needed something tangible, proof positive to convince the southern doubters of the need for secession. Pikes, like the one he lugged about the courthouse, would be that proof. The federal government had confiscated a thousand or more of them. To Ruffin, the pikes would be memorials to remind the South of the North’s perfidy.[xxiv]

He would order 15 of them from Alfred Barbour, superintendent of the arsenal, to be sent to him while he was staying with Alabama Senator Clement Clay and his wife in Washington. In his diary, Ruffin found the superintendent appointed by the Buchanan administration most condescending.[xxv]

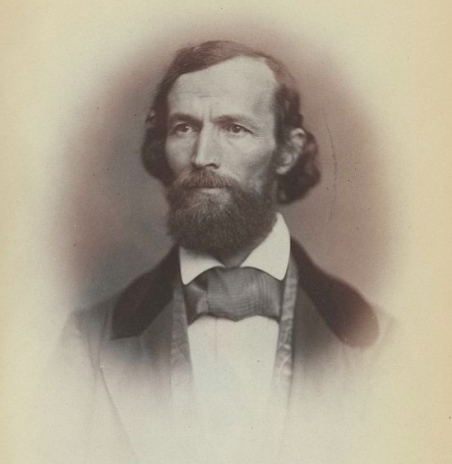

Alabama Senator Clement Clay

When preparing to leave in Washington a few days later, Ruffin asked Clay to accept the pikes if they ever arrived. His instructions were to send them to every governor of a slaveholding state along with a letter that Ruffin had written in which he asked them to display the weapons in prominent places as a lesson to all who might doubt northern intentions.[xxvi]

Months later, Ruffin was thrilled to see the pikes in the Senate Commerce Committee’s room, “beautifully labelled by the clerk.” Soon thereafter, he took some pikes with him to the chaotic Democratic Party convention in Charleston to drive the “approaching danger” point home to any wavering delegates from the slaveholding states.[xxvii]

By the time the pikes were ready to go to the governors, Ruffin had scratched Delaware off his list. With so few slaves left within its borders, the “First State” was now an apostate. Instead, he gave that pike as a special present to Clay and his wife, “who has taken much interest in this matter.”[xxviii]

But even Ruffin knew his warning was only going to the convinced. Would that be enough to make the final break with the North? To other minds, December 2, 1859, is marked as “the day of the martyrdom of St. John Brown.” They did not agree with Ruffin that Brown was a “thorough fanatic,” “the leader of the brigands, murderers and robbers” that terrorized Kansas and threatened more horrors upon Virginia.[xxix]

At that moment, in the North and even in New England, there were few who put Brown, as Henry David Thoreau did in a speech at Concord, Massachusetts, “like the best of those who stood at our bridge” to hold back with force the British. They may have admired Brown the man, but not his violent deeds.[xxx]

That all changed. When the shooting began in Charleston, where Ruffin was as well, firing the first gun, Brown the idol was being transformed into a martyr in the North.

As the war ground on and the Confederacy was being battered, Ruffin was never seen as an idol in the South.

On June 22, 1865, The New York Times reprinted an article from the Petersburg Express: “Edmund Ruffin, whose name is familiar with every one as a distinguished agriculturalist, and latterly as a politician, committed suicide on Saturday last in Amelia county, near Mattoox station. The sad act had been duly considered by him, as his diary is said to show. He seated himself, and placing the muzzle of the musket in his mouth, sprung the trigger and landed his spirit into the eternal world, with a desperate and unnatural coolness.”

In his death, Ruffin, like Brown, was elevated to the ranks of the martyrs by propagandists for the “Lost Cause.” Using his 12-page suicide note as a guide, Ruffin’s death was eulogized as “a final act of rebellion” rather than live under Yankee rule.[xxxi]

As he wrote, suicide was neither a crime or a sin. Ruffin saw his as “commendable.”[xxxii]

John Grady was a managing editor of Navy Times and is retired communications director of the Association of the United States Army. He has written for many publications, including Sea History, Naval History, The New York Times‘ Disunion blog, and is the author of Matthew Fontaine Maury: Father of Oceanography, which was nominated for the Library of Virginia’s 2016 non-fiction award.

[i] Anon., “Affairs at Charlestown,” Richmond Dispatch, Nov. 23, 24, 28, Dec. 2, 1859; A.W.S. Hawks, “Maj. Wells J. Hawks, C.S.A.,” Confederate Veteran, vol. 19, no. 8, (July 1911), 386-7; Terry Alford, Fortune’s Fool, The Life of John Wilkes Booth, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 73-7; Quartermaster Reports in John Brown Raid file, state archives, Library of Virginia; Anon., “Arrest of a Militia Officer—An Indignant Virginian,” Hartford Courant,” Dec. 8, 1859; Betty L. Mitchell, Edmund Ruffin, A Biography, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1981, 2, 138-40 (hereafter Mitchell, Ruffin).

[ii] Franklin Benjamin Sanborn (ed.), The Life and Letters of John Brown: Liberator of Kansas and Martyr of Virginia, (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1883), 146; Mitchell, Ruffin, 138-40, 143, 146; Edmund Ruffin, William Kauffman Scarborough, Avery O. Craven, (eds.), Diary of Edmund Ruffin: Toward Independence, October 1856-April 1861, vol. 1, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972), xvii, xix, xxii, xxiii, xxx, xxxi, xxxii, xxxix (on Ruffin biographical information not from diary) and (hereafter, Ruffin, Diary, volume number, page).

[iii] Edmund Ruffin, Political Economy of Slavery (Place unknown: Lemuel Towers, 1857 likely), 15 and “African Colonization Unveiled,” DeBow’s Review, vol. 29, no. 5, (Nov. 1859), 638-49; W.M. Matthew, “Edmund Ruffin and the Demise of the ‘Farmers Register,'” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 94, no. 1 (January 1986), 3-24; John M. McClure, “Edmund Ruffin (1794-1865,)” Jan. 4, 2014 in Encyclopedia Virginia, www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Ruffin_Edmund_1794-1865 (accessed Jan. 12, 2016).

[iv] Louis A. DeCaro Jr., “Fire from the Midst of You”: A Religious Life of John Brown (New York: New York University Press, 2002), 198; Jan Lewis, The Pursuit of Happiness: Family and Values in Jefferson’s Virginia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 53; Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1 citations on biographical information, particularly xxxi).

[v] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, xix, xxii. xxiii, xxxiii; William K. Scarborough, “Propagandists for Secession: Edmund Ruffin of Virginia and Robert Barnwell Rhett of South Carolina,” South Carolina Historical Magazine, vol. 112, no. 3-4 (July-October 2011), 126-38; Anon., “Resolutions of the Central Southern Rights Association,” DeBow’s Review, vol. 28, (March 1860), 356; Jefferson Davis, Lydia Lasswell Crist, Mary Seaton Dix, eds., Papers of Jefferson Davis, 1856-1860, vol. 6, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989), Footnotes, p. 352; James L. Abrahamson, Men of Secession and Civil War, 1859-1861, (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 2000), 57.

[vi] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 351, 363.

[vii] Same as note 5.

[viii] Ruffin, “Cassanda—Warnings,” Diary, vol. 1, 627-43.

[ix] See Mitchell note 2.

[x] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, xxxviii, 362; Henry Kollatz Jr., “An Unyielding Man,” Richmond Magazine, http://richmondmagazine.com/news/an-unyielding-man-04-26-2011/(accessed Jan. 18, 2018).

[xi] Anon.,”Affairs ay Charlestown,” Richmond Dispatch, Dec. 2, 5, 1859.

[xii] Same as note 10.

[xiii] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 368; “Arrest” in note 1.

[xiv] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, xxxi, 360-70; Testimony of Lewis W. Washington, Senate Select Committee on the Harper’s Ferry Invasion, www.wvculture.org (accessed Jan. 12, 2016); Kollatz as in note 10.

[xv] See Ruffin note 14.

[xvi] Edward Alfriend, “Recollections of John Wilkes Booth,” The Era: An Illustrated Magazine of Literature and General Interest, vol. 8 (October 1901), 603-5; Philip Whitlock, The Life of Philip Whitlock, photocopies from Jewish American Historical Foundation through Virginia Historical Society request, 37-8; James B. Averitt, Memoir of General Turner Ashby and His Compeers, (Baltimore: Selby & Dulany, 1867), 58, 60-1; George A. Townsend, The Life, Crime and Capture of John Wilkes Booth, (New York: Dick & Fitzgerald, 1865), 22-23.

[xvii] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 360-70.

[xviii] Alexander Boteler, “Recollections of the John Brown Raid by a Virginian Who Witnessed the Fight,” Century Magazine 26 (July, 1883), 399-411; Andrew Hunter, “John Brown’s Raid,” Publications of the Southern History Association, vol. 1, no. 3 (July 1897), 165-195; From Our Special Correspondent, “John Brown’s Execution,” New York Semi-Weekly Tribune, Dec. 6, 1859; Anon., “The Execution of John Brown, He makes No Speeches, He Dies Easy,” New York Daily Tribune, Dec. 2, 1859; Our Correspondent, “Affairs at Charlestown,” Richmond Dispatch, Dec. 2, 5, 1859; Francis H. Smith “Summary Report” in John Brown Execution section of Virginia Military Institute online archives, www.vmi.edu (accessed Jan. 12, 2016) and European Trip Letters, same location on VMI interest in agricultural education; Douglas Southall Freeman, R.E. Lee, vol. 1, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1935), 395-403; Oswald G. Villard, John Brown, 1800-1859: A Biography Fifty Years After (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1910), 463-5.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Mary Anna Jackson, Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson by his Widow (Louisville, 1895), 131; (Jackson’s letter is also available in John Brown Execution section of Virginia Military Institute online archives, www.vmi.edu, accessed Jan. 12, 2016.)

[xxi] Same as note 18; Kollatz as in note 10.

[xxii] Elizabeth Preston Allen (ed.), Life and Letters of Margaret Junkin Preston (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company, 1903), 111-6. (Preston’s letter is also available in John Brown Execution section of Virginia Military Institute online archives, www.vmi.edu, accessed Jan. 12, 2016.)

[xxiii] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 371.

[xxiv] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 25. Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 368, 378-80, 438-9.

[xxv] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 379-80, 383, 392.

[xxvi] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 25. Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 368, 378-80, 438-9.

[xxvii] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 431.

[xxviii] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, xxxix, 379-83.

[xxix] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 1, 503 footnotes, 506.

[xxx] Henry David Thoreau, “A Plea for Captain John Brown,” Delivered in Concord, Mass., Oct. 30, 1859, thoreauserver.org/pleas.html (accessed July 3, 2016).

[xxxi] Anon., “The Suicide of Edmund Ruffin,” TheNew York Times, June 22, 1865; Mitchell, Ruffin, 255-6; Eric Harry Walther, “The Fire-Eaters, the South, and Secession (Volumes I and II),” LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses, 4548, https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=5547&context=gradschool_disstheses (accessed Jan. 16, 2018), 352, particularly note 3; Mitchell, Ruffin, 255-6.

[xxxii] Ruffin, Diary, vol. 3, 935-46; Diane Miller Sommerville, ‘”Cumberer of the Earth’: Suffering and Suicide Among the Faithful in the Civil War South” in Craig Thompson Friend and Lorri Glover (eds.), Death in the American South (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 154-6.

Related topics: emancipation