Some people assume erroneously that words like “conservative” and “liberal” mean the same things over distance and time. A Progressive in Woodrow Wilson’s day, for example, would look quite different than someone calling themselves progressive today. The Liberal Republicans of the 1870s should not be confused with liberal Republicans today. Conservatives in the U.S. and Great Britain have some similarities, but also many differences.

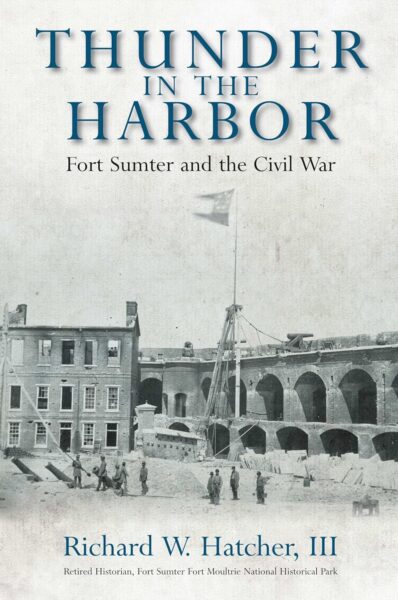

Along these lines, Holding the Political Center in Illinois opens with an evocative quote from the Chicago Journal. Conservatism, the newspaper asserted, “is a commendable element in our national politics” (1). Ian T. Iverson, currently associate editor of the John Dickinson Writings Project at the University of Delaware, contends that conservatism in the mid-nineteenth century was neither revolutionary nor reactionary. Indeed, for many people, conservatism “represented the political center, a middle path that balanced the passion of the moment with the wisdom of the past” (1). Iverson contributes to an important debate in the historiography of the U.S. Civil War era. One group of scholars have analyzed Black and white abolitionists and their efforts to destroy slavery. Another group of scholars, while not denying the importance of the abolitionists, focus instead on the significance of the conservative impulse and the importance of political moderates. Iverson analyzes Illinois politics from the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act to the aftermath of the firing on Fort Sumter and illustrates the importance of conservatism and union for many white Northerners.

Importantly, Iverson does not argue that conservatism stayed the same over the period he studies (1854-1861). Rather, “the boundaries of what constituted a conservative position shifted over time as unexpected events forced moderates to reevaluate how best to preserve the Union, republican government, and economic opportunity for free white men” (3). Some of the same people who denounced the repeal of the Missouri Compromise in 1854 rejected the Crittenden Compromise of 1861. However, he asserts, we should not see this as evidence of radicalization, but rather as self-proclaimed conservatives attempting to protect the legacy of the American Revolution from the forces they saw arrayed against it. Geographic, economic, and demographic diversity make the Prairie State a good laboratory in which to study conservatism. During the period covered by this book, Illinois politicians “battled ferociously to claim the political center and the mantle of conservative” (6) and “leaders on all sides orchestrated a drive to the ideological center” (6).

Stephen A. Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act and the rise of an anti-Nebraska movement in Illinois upended both the Whig and Democratic parties. It also sparked the formation of new political organizations, many of which claimed to be the “true” conservatives. When Owen Lovejoy and Ichabod Codding held a convention that attempted to organize a Republican Party in Illinois in 1854, they could not secure support outside northern Illinois. Part of the problem was that pro-Douglas newspapers reported that the convention called for the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, a charge which alienated conservatives. Douglas and his allies, who claimed to be the “true” conservatives, used the more radical Lovejoy and Codding to deride anti-Nebraska men as radicals. During the election of 1856, Democrats emphasized “the bisectional composition of the party and stressed ideological continuity and a respect for precedent in an effort to appeal to conservatives of all stripes” (63). Republicans countered by claiming that they were the true conservatives. The results proved mixed. On the one hand, Democrat James Buchanan defeated Republican John C. Frémont in the presidential contest; on the other, Republican William H. Bissell defeated Democrat William A. Richardson in the gubernatorial race. Iverson notes the importance of voters who cast ballots for both Bissell and Fillmore, the Know-Nothing candidate. Republican claims to conservatism were not as convincing when voters looked at John C. Frémont. Thus, enough voters in central and southern Illinois felt comfortable voting for Bissell, but not for Frémont.

Just as Douglas split the Democratic Party in 1854 with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, James Buchanan did the same in 1857-1858 with the Lecompton Constitution. Buchanan’s insistence that Douglas support the Lecompton Constitution caused Douglas to break with Buchanan and work with Republicans to defeat the Lecompton Constitution in Congress. Douglas’s break with Buchanan and “the Illinois Democracy’s claim to conservative moderation,” Iverson notes, “inspired respect within the state’s undecided political center and a sense of alarm among partisan Republicans” (102). The vast majority of Illinois Democrats and Republicans briefly converged in their hatred of the Lecompton Constitution and then “struggled to reassert their independent partisan identities while simultaneously capturing those centrist voters, especially former Whigs and Know-Nothings, who would ultimately decide whether Douglas would retain his Senate seat” (109). Illinois Republicans worked to distance themselves from charges of racial egalitarianism and “sought to establish themselves as the conservative defenders of free soil battling against a vacillating demagogue” (122). Douglas Democrats made their own claims to the political center. 1858 ended with Douglas winning reelection to the U.S. Senate, while Republicans won several statewide contests.

As they looked to 1860, Illinois Republicans faced new challenges. Democrats exploited John Brown’s raid to cast Republicans as dangerous radicals. In response, Lincoln crafted a conservative appeal to counter Democrat charges. Douglas Democrats and Republicans both claimed to “occupy the same middle ground” (168). Douglas Democrats “emphasized their independence from the radical Southerners who had long dominated the national Democracy and touted their devotion to the Union” (172). Voters, however, saw Lincoln as “a moderate alternative who could check the fanaticism of Southern planters without giving in to the radicalism of abolitionists” (173). After Lincoln’s election, Republicans and Democrats overcame their divisions, at least momentarily, to wage war in defense of the Union.

People often note how candidates for political office run to the left or to the right in the primary and then tack to the center for the general election. Iverson’s study of Illinois illustrates that making claims aimed at the center of the political spectrum is not a new phenomenon. However, his analysis raises two points worth considering. For one, Iverson notes that he and other scholars that study the conservative impulse and the power of political moderates “challenge the idea that the ideological extremes shaped the content and tenor of political discourse” (2). To an extent, he is right. Scholars should give more attention to how moderates and conservatives shaped political discourse. On the other hand, the reality is more complex than this statement allows. People at the edges and extremes of the political spectrum frequently shaped political discourse as much as moderates and conservatives. Iverson’s book illustrates how often people claiming to be centrists had to play defense and react to events, charges, and accusations from other groups. Second, at times Iverson appears overly eager to distinguish his book’s analysis from the interpretation in James Oakes in Freedom National. For instance, he writes that in 1854, “slavery had appeared an incidental issue, a mere bump on the road to continental domination” (205-206). Given that the country nearly tore itself to pieces in 1850 over the issue of slavery in the territories, this comment could stand revision.

Finally, it would be interesting if Iverson continued his analysis of Illinois into the Civil War and Reconstruction. Did both Republicans and Democrats still attempt to claim the political center during the U.S. Civil War and Reconstruction? The brief nonpartisan moment in the Prairie State quickly faded. When Democrats won control of the state legislature in 1862, Illinois soldiers grew furious and wrote to Governor Richard Yates that they stood ready to march to Springfield and remove the traitors. Douglas asserted in 1861 that Democrats would not be ranked with the party of traitors, but many soldiers had clearly made this linkage by early 1863. These points are beyond the scope of this monograph, but one hopes that Iverson will pursue them in another book that continues his analysis of the rough and tumble world of Illinois politics.

In sum, Iverson has produced a fascinating account of how both Democrats and Republicans ran to the center and sought to claim for themselves the mantle of conservatism. Readers would do well to compare Iverson’s analysis to Graham Peck’s in Making an Antislavery Nation: Lincoln, Douglas, and the Battle over Freedom (University of Illinois Press, 2017). Peck’s book has a longer time frame, but readers will be interested to see how both scholars, using many of the same documents, arrive at very different interpretations of the politics of the Prairie State in the 1850s and early 1860s. Anyone interested in the political history of the antebellum United States would be well advised to read this book and think carefully about Iverson’s argument about conservatism.

Evan C. Rothera teaches history at the University of Arkansas – Fort Smith.