Scott Hippensteel

Scott HippensteelThe ravine at the Pickett’s Mill battlefield. Union attackers crossed this ravine from the left to attack entrenched Confederates at the top of the slope to the right. The final upward slope of the assault covered a 7.5% grade.

What terrain features do the battlegrounds at Pickett’s Mill, South Mountain, Allatoona Pass, and Gettysburg have in common? All of them have at least one exceptionally high-relief slope that was crossed during a bloody infantry attack. At South Mountain, that’s most of the battlefield, comprising the steep grades of the gaps in the Blue Ridge. At Gettysburg, the initial Confederate assaults against Culp’s Hill and Little Round Top both qualify. Allatoona Pass and Pickett’s Mill, on the outskirts of Atlanta, were sites of infantry attacks against ridges—attacks launched out of mountainous ravines against well-fortified defensive positions.

From a tactical perspective, all these slopes were defensive force multipliers. They also influenced the nature of the many resulting casualties. At Pickett’s Mill, for example, signage describes the intensity of the fighting as being so great, and the volume of fire so tremendous, that the number of killed in the attacks (as opposed to only wounded) was “extraordinarily high, probably because many of the dead were shot repeatedly. The Confederates found one corpse with 47 bullet holes.” One historian of the fight at Pickett’s Mill offers another explanation for the disproportionately high number of killed in action: The men “were killed, many due to head wounds … because they were advancing uphill against entrenched forces.” Anecdotal evidence is also present to support this cause of death, with more than one eyewitness to the aftermath of that battle reporting the abundance of brains being scattered across the forest floor.

So, was the remarkably high fatality rate at these battles a factor of the volume of fire, with soldiers being shot multiple times, or the direction of fire, directly downslope, so that an approaching enemy target is more likely to suffer a gunshot to the head? Or was the lethality a combination of both factors, or something else, like the proximity of the combatants during fighting. Much of the most intense action at Pickett’s Mill, after all, took place in a fairly dense forest, where the combat would be expected to be at a closer and so deadlier range.

Anecdotal accounts can be full of exaggeration. As noted in the last Science and War column, eyewitness descriptions are often prone to embellishment to the point of ridiculousness. The same source who provided the grisly account of the corpse at Pickett’s Mill being riddled with 47 bullet holes, followed up by stating that he “could of walked for 2 or 3 hundred yards on the bodeys of the ded yanks.”

I was considering what caused a higher percentage of killed in action when I spent a day recently hiking in and out of the ravines at Pickett’s Mill and Allatoona Pass. Looking from above into those battlefields’ gullies, you can imagine the oncoming enemy emerging and approaching from below and picture the targets that might have been available to the defenders on the heights—their rifle sights filled entirely with the head and upper torso of the enemy.

Scott Hippensteel

Scott HippensteelThe ravine on the south slope of Allatoona Pass. Confederate attackers had to fight while climbing up this almost 10-degree slope and through abatis to reach the Star Fort at the top of the hill.

Contrast this scenario with another on a much larger scale, across much flatter ground: Pickett’s Mill versus Pickett’s Charge. On the third day at Gettysburg, Federal defenders found themselves shooting at the approaching Rebels from a much longer distance across open, undulating terrain. Wouldn’t this result in a much higher proportion of peripheral wounding hits to the legs and arms?

How much are the terrain (relief) and, to a lesser extent, land cover responsible for increased fatalities on a battlefield? Which of these factors is most important for determining the ratio of killed to wounded in action: the volume of fire (47 bullet holes!), the direction of incoming fire (brains everywhere), or the distance of fire (concentration of fatal bullet hits to the center of mass versus peripheral wounding strikes)?

The analysis of these fatal factors is complicated by two aspects of the data: First, many of the statistics simply don’t exist beyond a few firsthand accounts of bullet-riddled bodies and near decapitations; and second, much of the remaining data can only be compiled from sources that are unclear about what they are reporting with respect to fatalities and wounds. For example, do reports of soldiers who were killed in action include men who died of battle wounds a day (or even months) after the battle? If so, this might dramatically alter the ratio of killed to wounded for a particular fight.

Misuse of the term “casualties” in reporting about the Civil War is rampant, frustrating, and occasionally amusing. My favorite example comes from Thomas A. Desjardin’s excellent text about the Battle of Gettysburg, These Honored Dead, in which he describes movie producer Ted Turner’s promotion of his 1993 film Gettysburg: “He stated that more men died at Gettysburg than in the entire Vietnam War. A television audience of approximately forty million viewers heard this statement. Turner’s company perpetuated the misstatement on the packaging for the home video of the film, proclaiming to all who bought or rented the video that ‘when it was all over, fifty thousand men had paid the ultimate price.’”

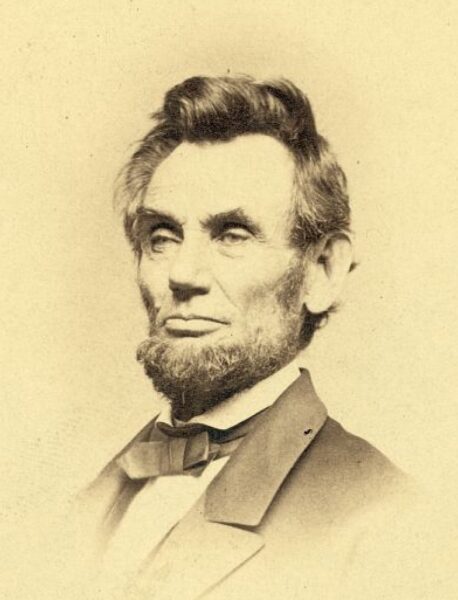

Turner was just confusing the terms “casualty” and “killed,” an oft-repeated mistake. What we are focusing on here, specifically, is two components of the term “casualties”: men killed in combat—not injured who might later die on the operating table or from complications and disease—and those who were wounded. How did terrain influence the ratio of killed in action to wounded?

To answer this question, I gathered data regarding the number of killed and wounded from battlefields across all theaters of the war and divided it according to the number of soldiers involved in the fight. On the broadest scale, the KIA/WIA ratio for entire armies (when primarily operating on the offensive or defensive) can provide general insights about the influence of terrain. Looking at the fatality ratio for other larger units, such as corps and divisions, provided more statistical information, but these casualties occurred over a larger geographical area with a variety of topographies present. For example, Joseph Hooker’s I Corps of the Army of the Potomac at Antietam attacked over relatively flat and open terrain during the morning phase of the battle, not its entirety.

The most useful data with respect to the ratio of KIA versus WIA comes from regiments and companies, smaller units where we have a better idea about where, specifically, on the battlefield they fought. Which Federal regiments, for example, charged up and out of the ravine in the woods at Pickett’s Mill, and how does their survival rate compare with similar-size units in attacks at Chancellorsville, Shiloh, or Stones River?

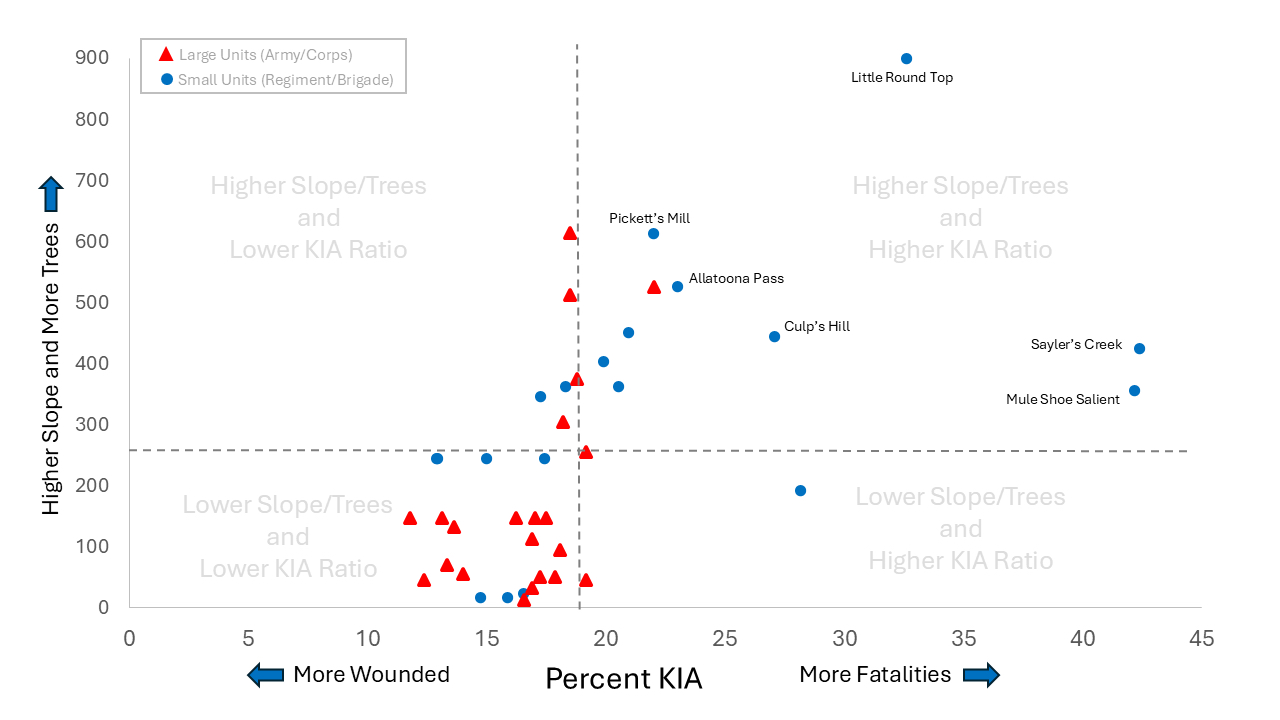

For this analysis, I compared two sets of data: one for larger units (armies, corps, divisions) and one for individual brigades and regiments. For each unit, I aggregated information about the number of men KIA, WIA, and the terrain where they fought (slope and forest cover).

The working hypothesis for this inquiry is that units attacking uphill will suffer more fatal gunshots to the head, neck, and upper/middle torso, resulting in a higher rate of fatalities in combat. When this uphill fighting takes place over relatively shorter ranges, the results are even more lethal.

Calculating the ratio of KIA to WIA is fairly straightforward, albeit with the complications already mentioned with respect to the data supply. For terrain, the influence of slope and range-reducing forest cover is more complicated. In short, I calculated a “terrain factor” that compares the average of the attacking slope (in degrees) and the percentage of forest cover, with the slope being deemed the more important contributor to the lethality of the landscape. When all the attacks are plotted together against the terrain factor (Figure 1), the mortal dangerousness of uphill attacks is clear. The correlation between slope and the percentage of fatalities is a moderately strong positive 0.55 (n = 58). The Confederate attacks at Little Round Top and the Star Fort above Allatoona Pass were extremely difficult slopes to traverse under fire, and the ratio of KIA to WIA was only around 1:3 (1 man killed for every three wounded), while the same ratio for more common attacks is around 1:4.5. The ratio for attacks across flat or gently rolling terrain, with few trees, is around 1:5.6 (16% fatality rate among those hit).

Scott Hippensteel

Scott HippensteelFigure 1: Terrain factor compared with fatality rate for attacking soldiers. Highest fatality rates are for smaller units fighting uphill in high-relief terrain.

With the caveat that these numbers don’t reflect other factors that might influence the rate of fatalities in a particular fight, such as artillery fire (e.g., canister at close range) or a vicious, close-quarters clash decided by hand-to-hand combat.

Other defensive influences might also play a major part in determining who dies in battle and who walks or crawls away. Fighting from behind a parapet or in a trench would probably increase the probability of a lethal head wound, because this is often the only part of a defender that might be visible, however briefly, to the enemy. At Allatoona Pass, for example, the men of the 36th and 46th Mississippi infantry regiments were attacking directly uphill (~25% fatality rate) against Union troops concentrated in a well-designed fort (>40% fatality rate). Similar KIA to WIA ratios can be found for defenders in the trenches of Petersburg, Vicksburg, and any of the coastal forts from along the Atlantic (1:3 ratio). For defenders without as much protection the ratio rises to 1:4 or 1:5 with more than 80% of the wounds inflicted being of the nonlethal variety (Figure 2).

Scott Hippensteel

Scott HippensteelFigure 2: Comparison of the fatality ratio (WIA: KIA) and the percentage of soldiers killed in action. Actions with more wounded plot to the lower left, while more deadly engagements are found to the upper right. As might be expected, smaller units usually had higher fatality rates when compared with entire corps or armies (for example, it is much more likely for an individual regiment to spend the entirety of a battle fighting defensively from behind a parapet than it is for an entire corps; as a result, individual unit statistics tend to favor the extremes).

Remember that when looking at this summary, we are only considering killed and wounded, not missing or captured, and that this lethality is not necessarily reflective of the overall casualty rate for a unit. The most lethal position to find yourself in on a Civil War battlefield would be in a fight between defenders behind earthworks and an enemy moving up a steep slope. While earthworks certainly provide a great deal of cover, those hit by the enemy are more likely to die from the gunshot. High relief terrain, like that covered by attacking Confederates at Culp’s Hill and Little Round Top, or the 15th New Jersey Infantry’s assault in the final stages at Sailor’s Creek, are nearly as deadly.

One final fatality factor that jumped out of the data had nothing to do with trenches or terrain. Brigadier General Edward Ferrero’s division of United States Colored Troops suffered 423 killed in combat at the Battle of the Crater, with 757 wounded (1:1.8 ratio, 36% fatality rate). Compare those figures with the white Union soldiers they were fighting alongside (1:10+ ratio, <10% fatality rate). Confederate rates of fatalities at the Crater, at first glance, appear remarkably similar to those of the black men they were fighting (1:2.0 ratio, 33% fatality rate); however, and importantly, these statistics for the Rebel losses include the 250+ men killed in the initial detonation of the mine under their lines. When you factor out the blast fatalities, the ratio of the Confederate killed in action and those of the (white) Union soldiers is essentially the same.

Scott Hippensteel is professor of Earth sciences at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where he focuses on coastal geology, geoarchaeology, and environmental micropaleontology. He has written four books about using science to illuminate military history: Sand, Science, and the Civil War: Sedimentary Geology and Combat (University of Georgia Press, 2023), Myths of the Civil War: The Fact, Fiction, and Science behind the Civil War’s Most-Told Stories (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), and Rocks and Rifles: The Influence of Geology on Combat and Tactics during the American Civil War (Springer Nature, 2018). His latest book, Civil War Photo Forensics: Investigating Battlefield Photographs through a Critical Lens, is forthcoming from the University of Tennessee Press.

Notes

1. This claim is repeated in the displays at the visitor’s center at the state park and is repeated on multiple outlets describing the battle, including Wikipedia (the site of the quote).

2. Dan Vermilya, Our Country’s Fiery Ordeal, “Pickett’s Mill State Battlefield,” posted May 5, 2011, accessed April 22, 2025. (fieryordeal.blogspot.com/2011/05/picketts-mill-state-battlefield.html).

3. This quote is from page 135 of Albert Castel’s Decisions in the West: the Atlanta Campaign of 1864 (1992). Also note that the “Yanks” suffered a little more than 200 dead in the entire battle, so to walk for several hundred yards stepping only on their corpses would have required concerted reorganization of the bodies.

4. This would be especially true with rifle muskets that fired with a low muzzle velocity; the large amount of bullet drop at 200 or 300 yards would lead to more nonfatal strikes to the legs and feet.

5. Thomas A. Desjardin, These Honored Dead (2003), 180–181.

6. I presupposed that the slope of an attack was more important for producing fatalities than the forest cover (direction of incoming fire more important that range of fire). To calculate the “terrain factor,” I determined the slope of a specific attack (in degrees) and divided it by the average slope for all attacks (~2.9°). Next, I calculated the percentage forest cover of a specific attack (based on historical maps) and divided it by the average forest cover for all attacks (26.5%). This provided a slope factor (from 0–416) and a forest factor (from 0–94). The final terrain factor was simply (2 X slope factor) + (forest factor), because the slope was considered the more important of the two influences on fatalities.

7. The Federals also had at least a few Henry repeating rifles in this fight, increasing their firepower dramatically.

8. Battle of Fort Pillow Confederate fatality rate: 1:6.1 ratio, 6% fatalities; Union (~50% black troops) fatality rate: 1:0.6 ratio, 63% fatalities.

Related topics: tactics

Absolutely fascinating. Challenging, too, given the contradictory claims. Didn’t Cleburne report that 700 dead Federals were counted in front of his lines at Pickett’s Mill? And what does the official return of Union casualties indicate ? Rather more than 200 killed, if memory serves me. The crucial question of the missing in action needs to be dealt with. This might effectively double the number of killed, especially if a severe repulse prevents the defeated force from counting its dead.

At Allatoona Pass the rebels reported fewer killed than the Yankees: about 125 v 144? But the Union commander. Corse reported that nearly 250 rebel dead were buried on the field, and Sherman alluded to another 100 who died of wounds in nearby woods. Look at the official returns for Iuka in September 1862: 140 odd Union posted as killed, and only about 85 confederates. But 250 rebel dead were reportedly counted on the field. Another variation of the ratio attends the way the forces are deployed. Buell’s Army of the Ohio at Shiloh counted only 244 killed against 1,800 wounded. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee returned 1,510 killed against about 6,600 wounded. But the number of died of wounds in Buell’s force was greater than the number initially returned as killed. The successful advance allowed his troops to recover badly wounded men and bring them to hospital, where they perished from their wounds. Their counterparts in Grant’s army were left to die on the battlefield. This accounts in part for the disparity in the ratio of killed. In so many of the battles, the number of missing was huge, and their fate was often fatal, even if the great bulk were unwounded prisoners. Chancellorsville, Chickamauga, Cold Harbor and Fredericksburg all had this in common for the North. Likewise Franklin, where only 189 Yankees were confirmed as killed, but many of the 1,109 missing shared their fate. So much more to say, but enough for now.

Phil Andrade