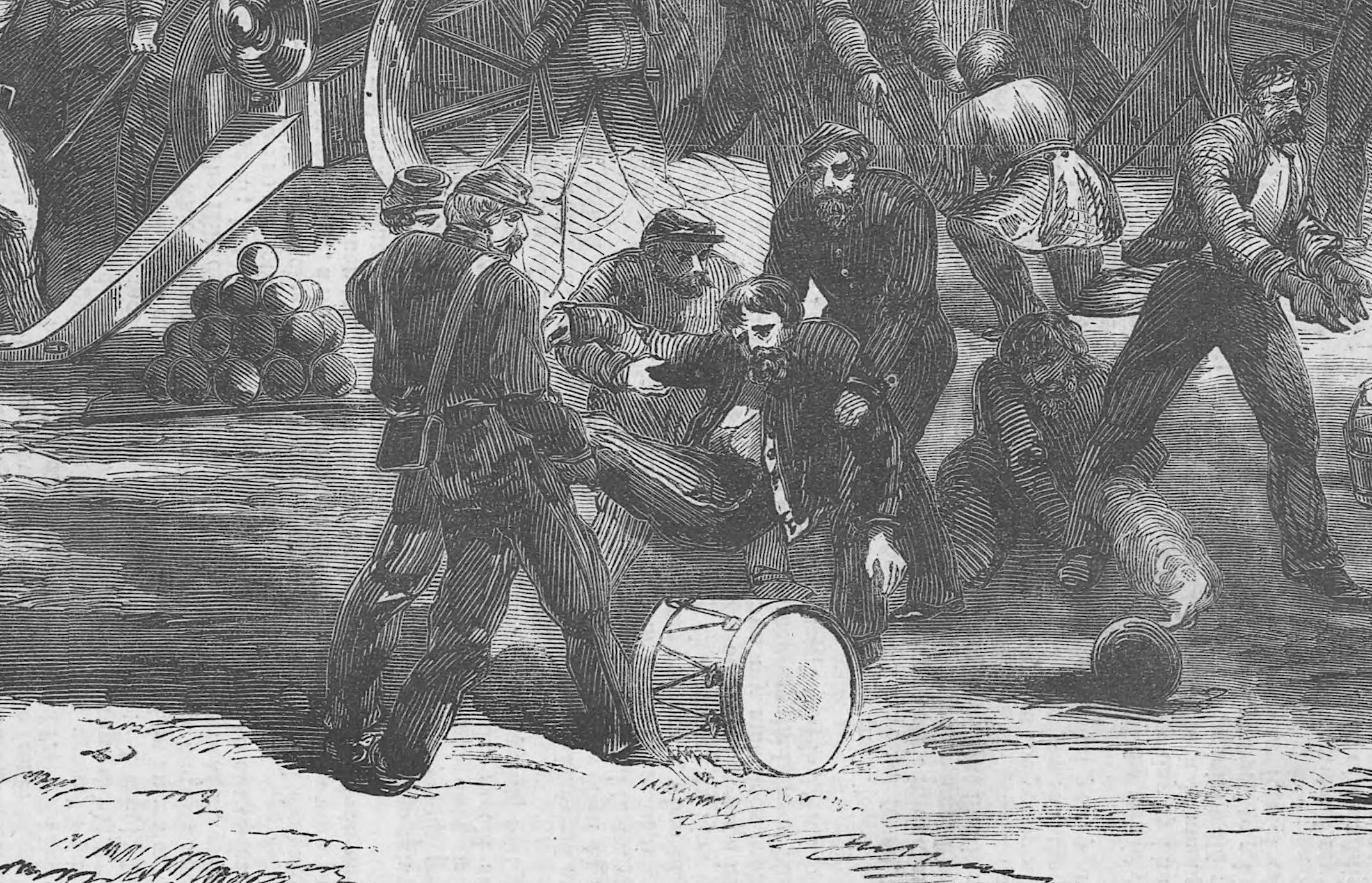

Harper's Weekly

Harper's WeeklyThis detail from a Harper’s Weekly illustration shows Union soldiers carrying a wounded comrade to safety during the Battle of Lexington, Missouri, in 1861.

In the Voices department of our Winter 2025 issue we highlighted quotes by Union and Confederate soldiers about their reactions to being wounded in battle. Unfortunately, we didn’t have room to include all that we found. Below are those that just missed the cut.

“It is useless for you to try to give me hope—it is useless.”

—Georgia officer W.F. Jordan, responding to his captain after the latter attempted to reassure him that the chest wound he received during the fighting outside Richmond in July 1862 wasn’t fatal. Jordan, a physician, was right.

“There are fifty chances in your case, and forty-nine of them are against you.”

—Spoken by a physician to Lieutenant Anderson H. French, 2nd Tennessee Cavalry, who had been shot through the bowels at the Battle of Tupelo, Mississippi, in July 1864. French, who replied “If there is even one chance for me, I will get it,” survived his wound and was still alive in 1887, the year a history of his regiment was published.

“I ran around till my boot was full of blood, and saw it was no use, so I lay down and was taken prisoner. I was held four days, during which time I had two small biscuits a day to eat, and it was over a day before my wound was looked to or washed. I am wounded in the left knee, the bone being a little shattered. It is a pretty bad wound, but I guess it will heal if nothing befalls it. If the ball had struck an inch and a half higher, it would have been all day with me. The brigade doctor said it was as narrow an escape as I would ever have.”

—Dwight A. Lincoln, 42nd Illinois Infantry, in a letter to his father after the Battle of Stones River, January 10, 1863. Dwight died 10 days later.

“But oh! my aching head, jaws and chest, as well as the extreme feeling of lassitude for the balance of the day. My face was like a puff ball, so quickly had it swollen, my chest at the point of the wishbone—so to speak—was mangled black and blue and resembled a pounded piece of steak ready to be cooked, and I was so nauseated, lame and sore all over, I dreaded to move.”

—Lemuel Abijah Abbott, 10th Vermont Infantry, in his diary about being hit by a piece of shell in the chest and by a minie ball in face at the Third Battle of Winchester, September 19, 1864

The Medford Historical Society & Museum

The Medford Historical Society & MuseumUnion officer Wilder Dwight

“I am wounded so as to be helpless. Good by, if so it must be. I think I die in victory. God defend our country. I trust in God, and love you all to the last. Dearest love to father and all my dear brothers. Our troops have left the part of the field where I lay.”

—Lieutenant Colonel Wilder Dwight, 2nd Massachusetts Infantry, in a note to his mother written as he lay wounded on the battlefield at Antietam, September 17, 1862. Dwight died two days later.

“[A] rebel from behind a tree … took deliberate aim at me, and fired. The bullet knocked me from my horse…. I supposed I was mortally wounded.”

—Captain Henry W. Chester, 2nd Ohio Cavalry, in a postwar letter about being shot in the head at the Battle of Sailor’s Creek in April 1865. Chester survived and was 77 when he died in 1918.

“I think I shall be better shortly. I have great confidence in the recuperative power of my constitution, and trust it will be sufficient to eliminate this poison.”

—Union surgeon Alfred L. Castleman, in his diary about pain in his injured finger—“the result of a scratch by a spiculum of bone, whilst I was examining a gangrenous wound at Antietam”—that had run up his arm to his shoulder, September 24, 1862

“Not one in the long procession of ambulances uttered a complaint. Did they really suffer pain from their wounds? This question was asked by thousands, and the reply was, ‘not much.’”

—Confederate War Department employee John Beauchamp Jones, on the arrival in Richmond of Confederate soldiers wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines, in his diary, May 31, 1862

“I drop you a line this afternoon to relieve your anxieties, as you will probably hear that I am wounded before this reaches you…. The ball glanced from a tree, and just grazed my knee at the joint. I thought at first the joint was shattered all to pieces, but soon found that I could move it. I stayed on the field mounted on my horse until nine in the evening, and then returned to camp. To-day I am very stiff….”

—Major Mason Whiting Tyler, 37th Massachusetts Infantry, on a wound he received during the fight for Petersburg, Virginia, in a letter home, March 26, 1865

“The boys soon rip[p]ed my pants open and there it was, bleeding very freely. No mistake I was wounded…. I was … carried to the field hospital. When it comes my turn I am put on a table with all the instruments close by like I was to be carved up into soup bones. The Surgeon examined my wound, run his finger in the hole—but couldn’t put it clear through so he put the other finger in the other side, then he run his fingers in and out, first one then the other, until as he said there was no foreign substance left in there to hinder it from healing up.”

—Confederate officer Samuel T. Foster, on the wound he received at the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, in his reminisces of the war. Foster’s wound healed and he rejoined the army months later.

“I, with some fifty others, now started on foot (as did hundreds of others whose horses were fagged out), and just as we were about darting into a wild, woody recess, the better to aid our flight, a party of about two hundred rebels flanked us on the right, calling loudly on us to surrender. Some did; but others more anxious for their freedom, among whom I was, continued to flee: when some were stricken down dead, and one of those death-dealing blackguard bullets, fond of a fleshy residence and a bloody drink, took up its lodging in the calf of my right leg, and causing its unfortunate owner to whine and growl with an agony as keen as his late laughter was hilarious.”

–John England, 2nd New York Cavalry, on being wounded and captured during the failed Wilson-Kautz raid against the Petersburg and Danville Railroad, in a letter to a friend, November 28, 1864

“I was standing, or rather kneeling, behind a little bush reloading my musket, just before the rebels engaged in this close work retreated. Suddenly I felt a sharp pain in the shoulder, and fell to the ground. Jumping up, one of our boys asked me if I was hurt. I replied I thought not, and drew up my musket to fire, when he said: ‘Yes; you are shot through the right shoulder.’ I think it was this remark, more than the wound, which caused the field, all at once, to commence whirling around me in a very strange manner. I started to leave it with a half ounce musket ball in my shoulder, and once or twice fell down with dizziness, but in a short time recovered sufficiently to be able to walk back to Springfield, nine miles, where the ball was taken out.”

—An Iowa soldier, in an account of his wounding during fighting in Missouri in 1861, published in The Scientific American

“One of the Fire Zouaves was shot in the battle of Bull Run in a manner very surprising to himself and every person who has heard the story. While fighting away like a tiger with his mouth open on account of excessive heat and thirst, a musket bullet from the enemy entered his mouth, then passed up at the back of his upper jaw and out of his face just behind his left eye. This bullet made its entrance and exit so silently and scientifically that the Zouave actually knew nothing about it until some time afterwards, when he was told that something had happened to his face, his informant discovering the blood trickling down his cheek. He then asked his comrade to examine his face, who discovered what had occurred. The Zouave states that he felt a peculiar prick under his eye, but had no idea it was caused by a musket shot, and he thinks that he fired two rounds after receiving the wound before he noticed the sensation which he described.”

—From an article titled “Curious Course of a Bullet,” which appeared in the August 17, 1861, issue of The Scientific American

Library of Congress

Library of CongressThe First Battle of Bull Run as depicted by artist F.O.C. Darley.

“[A] man from some other regiment joined my company formally and asked for orders. I pointed out the enemy and told him to fire. As he raised his gun up to fire, a ball struck him in the head, spattering some of his blood in my face. He asked me to take care of him. I told him I could do nothing for him, but I thought God would, and as I said this, he fell over dead.”

—Captain George W. Hooper, 6th Alabama Infantry, on an incident during the Battle of Seven Pines, in a letter to the Georgia newspaper Columbus Sun, June 2, 1862

“[T]he enemy continued to pour in the leaden rain, and at every instant the dull ‘chuck’ of a flying missile could be heard to strike the body of some comrade in the darkness around … and he either fell dead or lay bleeding.”

—A soldier in the 2nd Georgia Infantry, on the fighting during the Seven Days Battles, in a letter to the Savannah Republican, July 28, 1862

“It was a battered looking procession; and yet, I suppose that people will be surprised to hear, it was as cheerful a lot of fellows, as you can imagine. Wounded men coming from under fire are, as a rule, cheerful, often jolly. Being able to get, honorably, from under fire, with the mark of manly service to show, is enough to make a fellow cheerful, even with a hole through him.”

—Confederate artillerist William Dame, on observing wounded comrades heading for field hospitals during the Battle of the Wilderness, in his memoir of the war. He added: “Of course I am speaking now of the wounded who can walk, and are not utterly disabled.”

“I vow to gosh, that’s too bad! I wasn’t a bad looking chap before, and now I’m done for; won’t there be a thunderin’ scar? And what on earth will Josephine Skinner say?”

—A Union soldier, shot through the cheek, to hospital nurse Louisa May Alcott, who had brought him a mirror to assess his injury, as told in her memoir of the war

“Oh! wouldnt it be nice to get a 30 days leave and go home and be petted like a baby, and get delicacies to eat … and then if I ever run for a little office I could limp and complain of the ‘old wound.’”

—Confederate soldier E.J. Ellis, pining for a slight injury in a letter to his mother, February 15, 1863

“I don’t mind the pain so much, sir, but I wouldn’t have both of my eyes shot out for twenty-five dollars.”

—A Union prisoner, blinded by a bullet, in response to a Confederate who commented that “his wound must be very painful,” as recorded by Virginia artillerist William S. White in his diary, June 27, 1862

“My leg is a regular old weather clock for I can tell when it is going to be bad weather—it feels num and as if it had been froze and was not thourally thawed out yet.”

—Charles Goddard, 1st Minnesota Infantry, on dealing with the effects of a wound received at the Battle of Gettysburg, in a letter to his mother, December 4, 1863

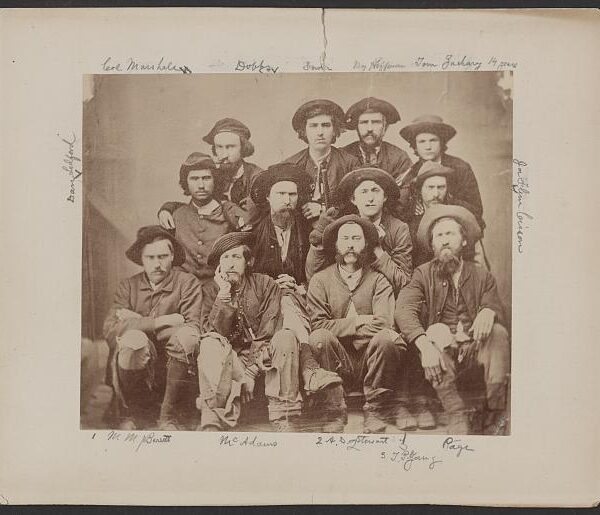

The Colonel's Diary (1922)

The Colonel's Diary (1922)Captain Oscar L. Jackson

“I have recollection of almost nothing that happened till I recovered consciousness the second or third day after the battle, when I aroused from my stupor but could scarcely recollect what had happened. Both eyes were swelled completely shut from the wound and although it was day time I supposed it was night…. Soon I was able to remember where I had, as it were, quit the world two days before, but I was not really certain whether any of the men of my company were dead.”

—Captain Oscar L. Jackson, 63rd Ohio Infantry, on being wounded below the right eye at the Battle of Corinth, in his diary, October 4, 1862. Twenty-three of Jackson’s 34-man company had been killed or wounded in the fight.

“Of these by far the larger number felt, when shot, as though some one had struck them sharply with a stick, and one or two were so possessed with this idea at the time, that they turned to accuse a comrade of the act, and were unpleasantly surprised to discover, from the flow of blood, that they had been wounded. About one-third experienced no pain nor local shock when the ball entered. A few felt as though stung by a whip at the point injured. More rarely, the pain of the wound was dagger-like and intense; while a few, one in ten, were convinced for a moment that the injured limb had been shot away.”

—Physicians S. Weir Mitchell, George R. Morehouse, and William W. Keen, on their general observations of soldiers’ reactions to being wounded, in their 1864 book on the subject

“The feeling is simply one of shock, without discomfort, accompanied by a peculiar tingling, as though a slight electric current was playing about the site of injury. Quickly ensues a marked sense of numbness involving a considerable area around the wounded part.”

—A.B. Isham, 7th Michigan Cavalry, in a postwar article about his wartime wounding

“I remember no acute sensation of pain, not even any distinct shock, only an instantaneous consciousness of having been struck; then my breath came hard and labored, with a croup-like sound, and with a dull, aching feeling in my right shoulder, my arm fell powerless at my side, and the Enfield dropped from my grasp.”

—Ohio soldier Ebenezer Hannaford, in a wartime account of begin wounded in the shoulder at the Battle of Stones River

Sources

William B. Styple, ed., Writing & Fighting from the Army of Northern Virginia (2003); Hancock’s diary (1887); Life and letters of Wilder Dwight (1867); Soldiers’ Letters, from Camp, Battlefield and Prison (1865); War Diary of Luman Harris Tenney, 1861-1865 (1914); The Army of the Potomac. Behind the Scenes. (1863); A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital (1866); Recollections of the Civil War (1912); One of Cleburne’s Command: The Civil War reminiscences and Diary of Capt. Samuel T. Foster, Granbury’s Texas Brigade, CSA (1980); Soldiers’ Letters, from Camp, Battlefield and Prison (1865); The Scientific American, August 17, September 21, 1861; From the Rapidan to Richmond (1920); Hospital Sketches (1863); Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Johnny Reb (1943) and The Life Billy Yank (1952); The Colonel’s Diary (1922); Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves (1864); Earl J. Hess, The Union Soldier in Battle (1997).