On May 24, 1861, 24-year-old Elmer E. Ellsworth—colonel of the 11th New York Infantry—was shot and killed by the pro-secessionist proprietor of the Marshall House, an inn located in Alexandria, Virginia, after the young officer removed a Confederate flag that flew from its roof. Ellsworth, who had risen to fame before the war while touring the country with his military drill team, the Zouave Cadets of Chicago, quickly became a martyr throughout the North, the phrase “Remember Ellsworth” used as a rallying cry by young Union volunteers. Shown here are images that reflect Ellsworth’s deep popularity, in life and death, from coverage in the press to mementos of remembrance.

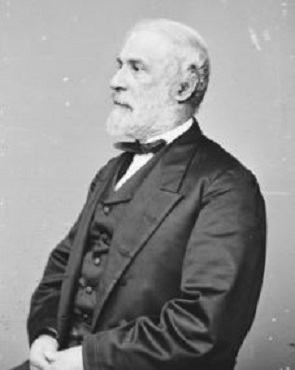

Ellsworth had this photo taken of himself in Mathew Brady’s New York studio. Copies of this and other images of the young celebrity found their way into the personal collections of countless northerners, before and during the Civil War. (National Portrait Gallery)

![Ellsworth (standing second from right in this illustration from Harper's Weekly) earned fame as the head of his military drill team, the United States Cadets, or the Chicago Zouaves. After a performance in New York in July 1860, the editors of Harper's Weekly published this image and wrote of the group, "[T]heir drill, their evolutions, their dash and elan are peculiarly their own, and have aroused the enthusiasm of all our military men." (Harper's Weekly)](https://www.civilwarmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2.--900x583.jpg)

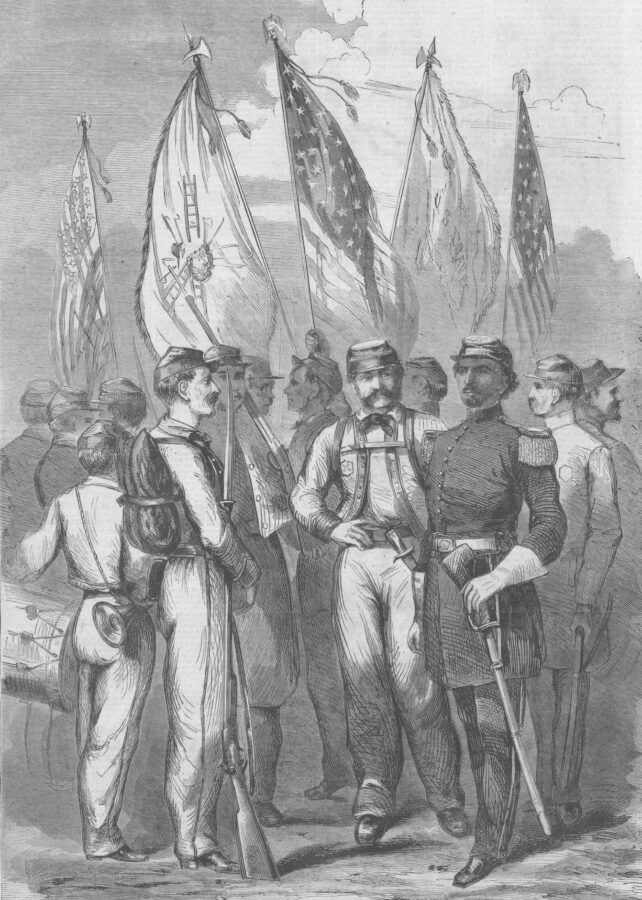

Ellsworth (standing second from right in this illustration from Harper’s Weekly) earned fame as the head of his military drill team, the United States Cadets, or the Chicago Zouaves. After a performance in New York in July 1860, the editors of Harper’s Weekly published this image and wrote of the group, “[T]heir drill, their evolutions, their dash and elan are peculiarly their own, and have aroused the enthusiasm of all our military men.” (Harper’s Weekly)

After the firing on Fort Sumter, Ellsworth raised—and commanded—the 11th New York Infantry (known as the “Fire Zouaves”) from the ranks of New York City’s volunteer firefighting companies. Harper’s Weekly published this illustration, along with a profile of Ellsworth and the men of the 11th New York, in its May 18, 1861, issue. (Harper’s Weekly)

![On May 9, 1861, Ellworth's Fire Zouaves helped save the day at Washington D.C.'s Willard's Hotel, where a fire had broken out. A report that accompanied this illustration in Harper's Weekly read in part, "Colonel Ellsworth ordered one hundred Zouaves to assist in extinguishing [the fire]. The order was followed by nearly the whole regiment jumping from the windows of the Capitol and scaling the fences.... They worked like heroes, performing wonderful feats of agility and bravery. They formed pyramids on each other's shoulders, climbing into windows, scaling lightning-rods, and succeeded in two hours in saving the whole structure." (Harper's Weekly)](https://www.civilwarmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/4-762x900.jpg)

On May 9, 1861, Ellworth’s Fire Zouaves helped save the day at Washington D.C.’s Willard’s Hotel, where a fire had broken out. A report that accompanied this illustration in Harper’s Weekly read in part, “Colonel Ellsworth ordered one hundred Zouaves to assist in extinguishing [the fire]. The order was followed by nearly the whole regiment jumping from the windows of the Capitol and scaling the fences…. They worked like heroes, performing wonderful feats of agility and bravery. They formed pyramids on each other’s shoulders, climbing into windows, scaling lightning-rods, and succeeded in two hours in saving the whole structure.” (Harper’s Weekly)

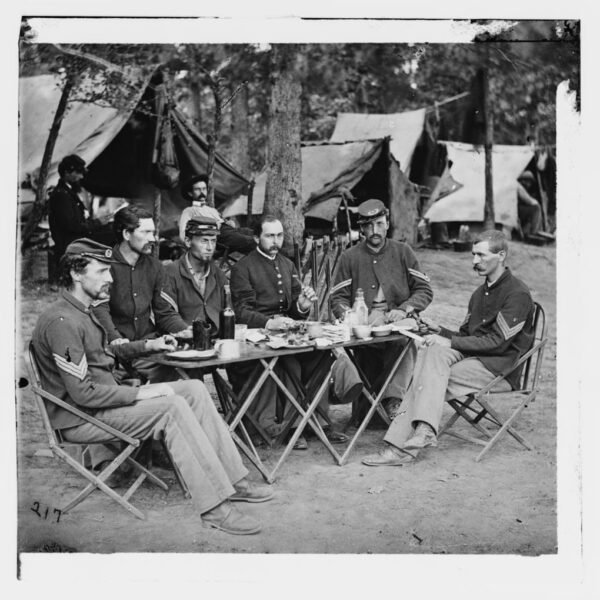

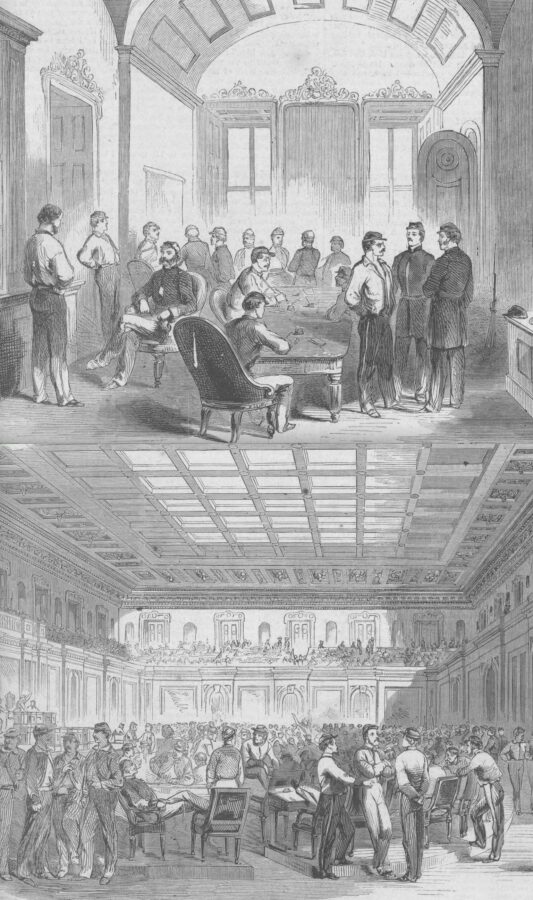

Press coverage of Ellsworth and his Fire Zouaves remained strong during the war’s early weeks. To satisfy their readers’ interest in the young celebrity and his men, Harper’s Weekly published illustrations of Ellsworth’s headquarters at the Capitol (top) and of the 11th New York’s temporary quarters at the House of Representatives (bottom). (Harper’s Weekly)

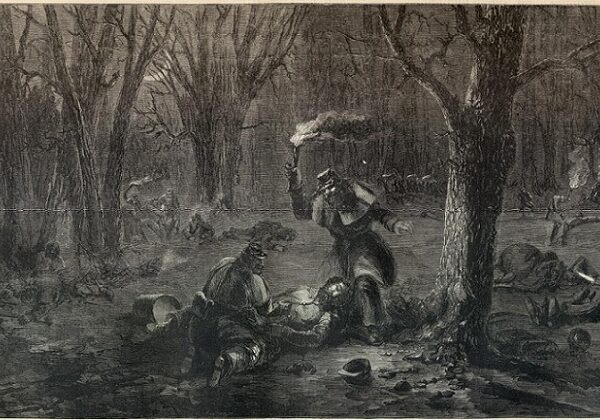

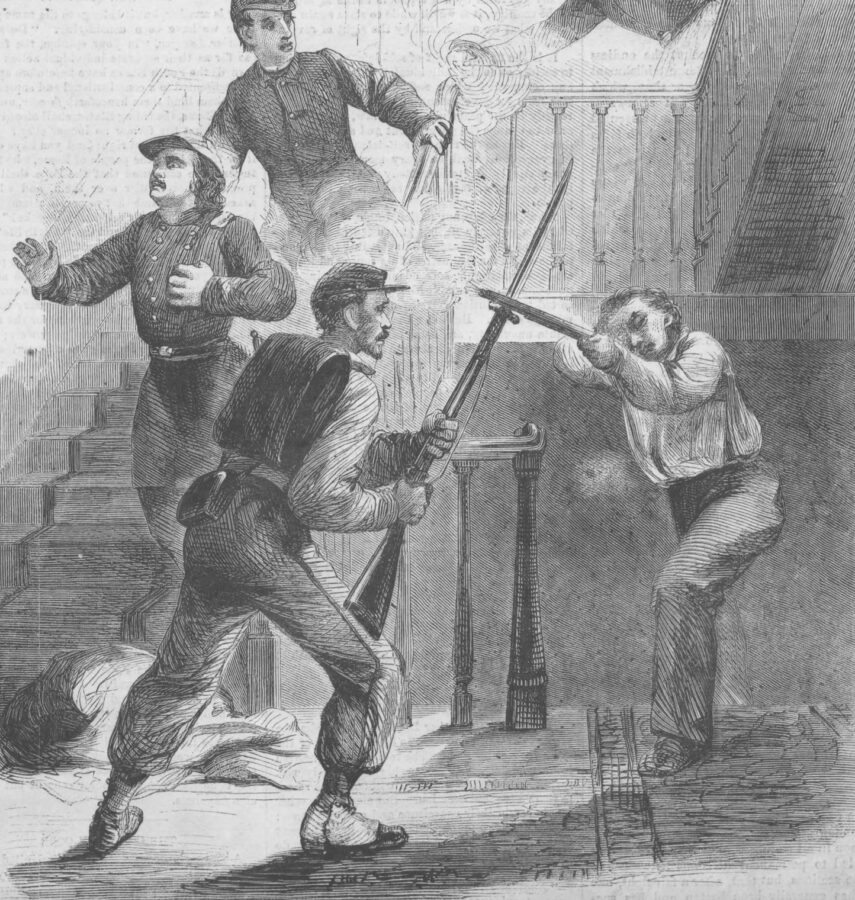

On June 15, 1861, Harper’s Weekly published this image of Ellworth’s death on May 24 at the Marshall House alongide an article titled “The Murder of Ellsworth.” One of the Fire Zouaves present at the time, Private Frances Brownell, is pictured in the foreground. Brownell instantly shot and killed the inn’s proprietor, James Jackson, after the latter fired at Ellsworth. (Harper’s Weekly)

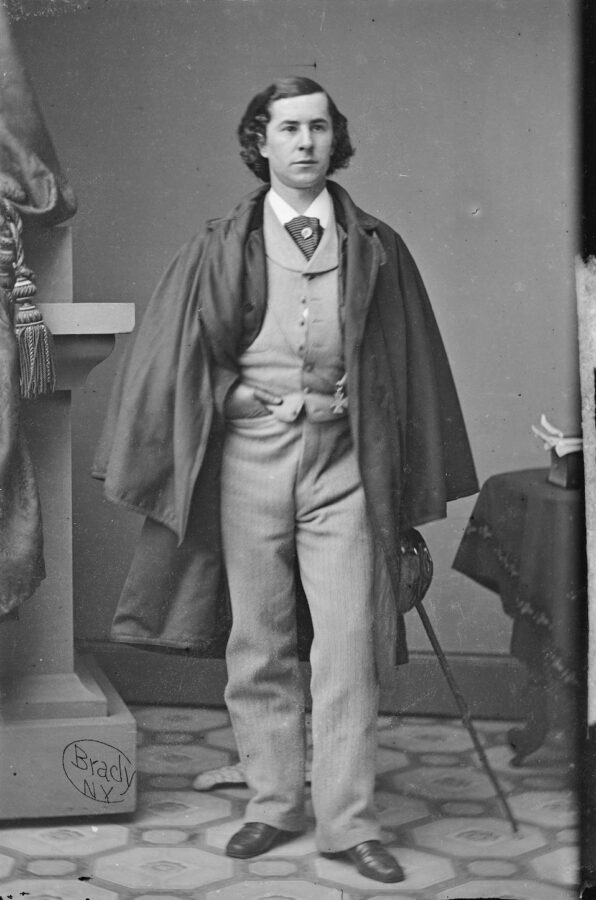

Private Brownell, shown here posing in Mathew Brady’s studio with the secessionist flag Ellsworth had removed from the Marshall House at his feet, became a minor celebrity after his actions on May 24. He soon after earned a commission in the Regular Army, in which he would serve until 1863. In 1877, he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Marshall House. (Library of Congress)

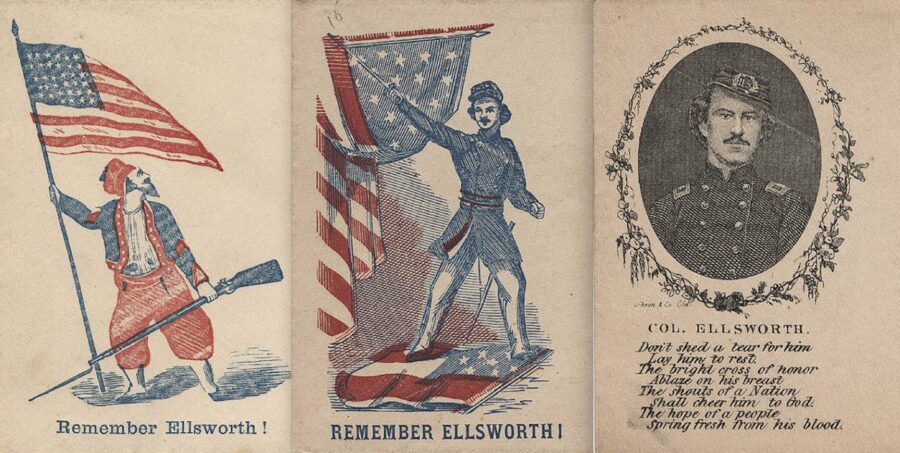

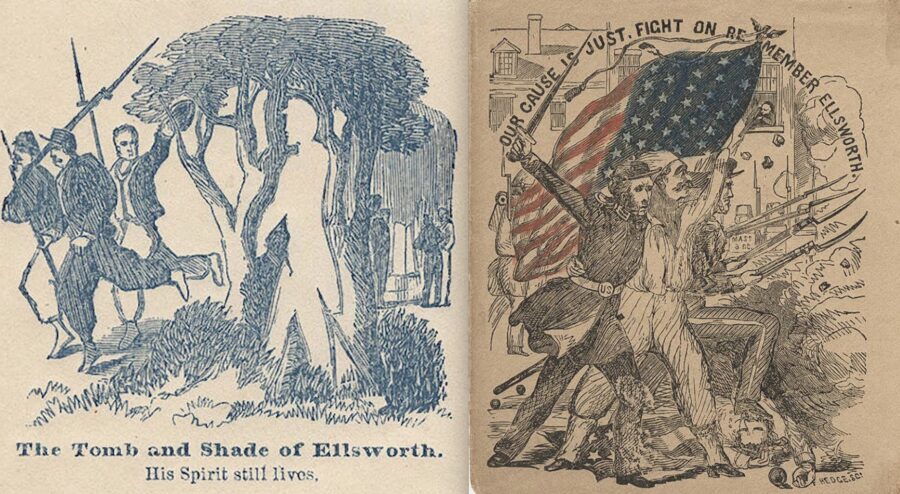

Though he had been killed before the war’s first major land battle was fought, Ellsworth’s death had a significant impact by galvanizing the northern populace. Shown here (above and below) is artwork from patriotic envelopes published during the war that used Ellsworth as a rallying cry. (Both South Caroliniana Library)

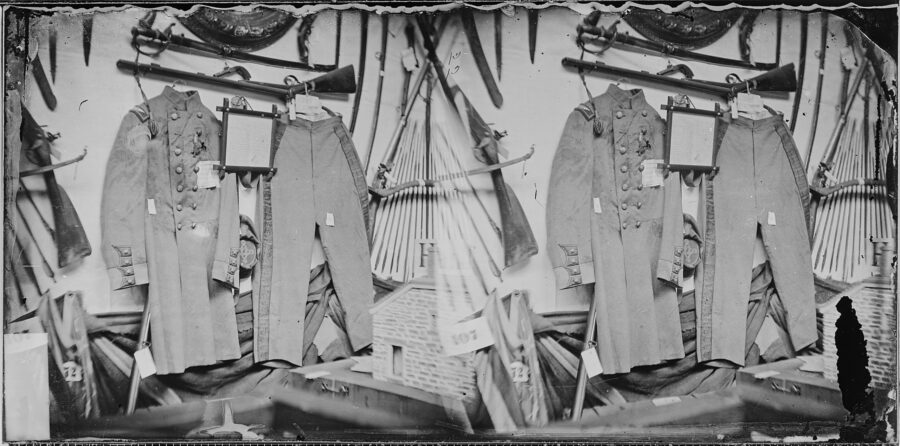

The North’s fascination with Ellsworth survived his death. Shown here is a wartime display of the uniform Ellsworth was wearing when he was killed, the effect of the fatal shotgun blast to his chest evident by the large hole in the coat. (National Archives)