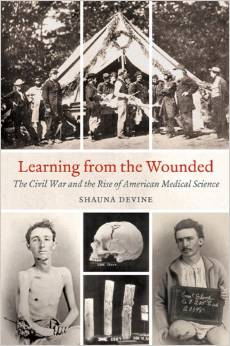

Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science by Shauna Devine. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. Cloth, ISBN: 978-1469611556. $39.95.

The sesquicentennial of the American Civil War has produced re-enactments, special museum exhibits, conferences, public events, and new books. The public perception of the medical dimension of the war, however, continues to retail in old narratives and Hollywood myths, from Scarlett O’Hara placing thermometers in the mouths of wounded Confederate soldiers to bloody amputations being conducted without anesthesia. In the early twentieth century, S. Weir Mitchell, one of the war’s scientifically oriented physicians, noted the proliferation of memorials and monuments to generals and regiments, but found none that acknowledged doctors. Ironically, disfigured and disabled soldiers were omnipresent fixtures within the American landscape of the 1860s and, later, and a continuing subject of political and social concern.

The sesquicentennial of the American Civil War has produced re-enactments, special museum exhibits, conferences, public events, and new books. The public perception of the medical dimension of the war, however, continues to retail in old narratives and Hollywood myths, from Scarlett O’Hara placing thermometers in the mouths of wounded Confederate soldiers to bloody amputations being conducted without anesthesia. In the early twentieth century, S. Weir Mitchell, one of the war’s scientifically oriented physicians, noted the proliferation of memorials and monuments to generals and regiments, but found none that acknowledged doctors. Ironically, disfigured and disabled soldiers were omnipresent fixtures within the American landscape of the 1860s and, later, and a continuing subject of political and social concern.

Hospitals occupied such a distinctive presence in cities North and South that they became visitor attractions. Poet Walt Whitman immersed himself in the hospital universe as a volunteer and thought that the “real” history of war would not get in the books; that within hospitals could be found the true “marrow of tragedy.” As miniature city-states of the ill and wounded, hospitals were built to innovative designs; collected vast numbers of patients; required large, competent administrative and supply structures and staffs; managed their own economies, which consumed enormous quantities of supplies; pioneered social experimentation (such as the advent of women within institutional health care); and created an ethos of scientific inquiry and clinical investigation. The latter topic is the subject of the book under review.

Professor Shauna Devine, who teaches medical history at Western University, Canada, has turned her doctoral dissertation on the development of scientific medicine during the Civil War into a stimulating and persuasive book that functions as a benchmark for future scholarship. Devine observes that the doctors of the late nineteenth century who formed and led new medical associations and pioneered specialty fields shared the common experience of Civil War, a circumstance frequently ignored in histories of the rise of American medical science. “The war, then, was more than a broad school of experience; it was also a conduit for the production, development, and dissemination of new medical ideas” (5). The book alternates between institutional developments within the medical schools and military medical bureaucracy and the experiences of individual physicians. In common with other recent medical histories, activities of the North receive more attention because of its better resources and abundant extant documentation, although Southern physicians certainly approached matters in similar ways but under impoverished conditions. Most Confederate medical records were lost during the destruction of Richmond.

Devine “investigate[s] how [physicians’] experiences affected the way individuals practiced and studied medicine [and] the complex questions that led to the shift in emphasis from pathological anatomy, experimental physiology, chemistry, microscopy, and medical specialization . . . [and] how medicine and [the] understanding of disease were structured, investigated . . . and taught and learned during the war, and how this medical knowledge was disseminated in the later nineteenth century” (9). The locus of this investigation is the Army Medical Museum, created in Washington, D.C., as a clearinghouse for ongoing surgical work on battlefield and in hospital. The museum not only amassed information, mostly through correspondence and reports, but also specimens which surgeons (all military doctors were called surgeons) sent to the museum or which were collected in the field. The military required physicians to submit reports and specimens, inculcating an ethos of clinical inquiry through research. The concentrated numbers of casualties enabled systematic studies of phenomena, especially through autopsies — work that became routinized to a new standard of performance.

The work of one military doctor, Philadelphian Joseph Janvier Woodward, is illustrative. Charged with founding the Army Medical Museum, “he sought to create a new investigative framework in which to understand the nature of disease. Second, he wanted to become part of the international scientific community then composed of those engaging in microscopial work related to human normal or pathological conditions . . . .” (78). A polyglot who employed his language skills in translating new medical texts into English, Woodward had read the work of Germany’s Rudolph Virchow, professor of medicine, who receives credit for positing the idea that the unit of life is the cell. Virchow believed that disease could spread from cell to cell through mitosis, the process by which cells reproduce. This idea later became pivotal to understanding how viruses work. Woodward arranged for the translation of Virchow’s great work, Cellular Pathology, and its distribution to all Army physicians. Woodward admired Virchow’s conclusions as much as the German environment of “pure research” that enabled the inquiry, and he deepened his understanding through correspondence with Virchow. Civil War doctors might isolate and examine the evidence of disease—generally labeled lesions—but now they had a new insight. Woodward even purchased microscopes for hospitals to explore cellular anomalies, an instrument largely absent from the medical armamenta before the war. He also pioneered photomicrography of pathological tissues and created a special section for them in the museum. The museum anchored the post-war publication of the great medical compendium, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, a scientific benchmark and milestone in printing.

Devine explores and analyzes work with gangrene and erysipelas (diseases both caused by streptococcus bacteria) and cholera outbreaks to make comparable arguments about the emergence of professional specializations and the articulation of new modes of clinical inquiry and experiment. Through abundant examples of how physicians created new ways to discuss and analyze disease, the reader sees how close wartime physicians came to making key connections between contagion, disinfection, and the nature of disease. The author tantalizes with observations on how Jacksonian American ideals moderated the medical management of diseases, quarantine, and the debate about contagion— topics I wished received fuller discussion. Devine’s book is best read in context with Margaret Humphreys, Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War [2013] which, through a “gendered approach,” “examines how concepts of masculinity played out in the new social sphere of the war . . . how perceptions of what behaviors and attitudes were masculine or feminine affected the structure of medical care” (2). Also, Ira M. Rutkow’s Bleeding Blue and Gray: Civil War Surgery and the Evolution of American Medicine [2005] blends military, social, political, and economic contexts to illuminate the medical realm.

Robert D. Hicks, Ph.D., is Director of the Mütter Museum/Historical Medical Library and the William Maul Measey Chair for the History of Medicine at The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.